Skift Take

The cacay nut is a perfect example of how tourists can directly benefit entire countries simply by buying products for their own wellness in cities like Bogotá that help support poorer regions throughout Colombia. Maybe someday being a tourist will become less about being a foreigner and more about being a better global citizen.

Skift Senior Research Analyst Rebecca Stone is traveling the globe over the next year as part of Remote Year, a program that brings together working professionals to travel, live, and work remotely. She'll spend a month in 12 cities around the world that include Cape Town, Lisbon, Valencia, Sofia, Hanoi, Chiang Mai, Kyoto, Kuala Lumpur, Lima, Medellin, Bogotà, and Mexico City. And every month she'll take you along for part of the journey with a feature about her observations based on firsthand reporting and data about the changing travel industry. She'll do the jet lag. All you have to do is kick back and enjoy her compelling dispatches.

I was out to eat at Restaurante Leo celebrating the birthdays of two dear friends when I first heard about the cacay tree. Restaurante Leo, located in downtown Bogotá, Colombia, was created by award-winning chef Leonor Espinosa to showcase and celebrate the incredible biodiversity and ecosystems of Colombia. The country is the second most biodiverse country in the world, after all (after Brazil).

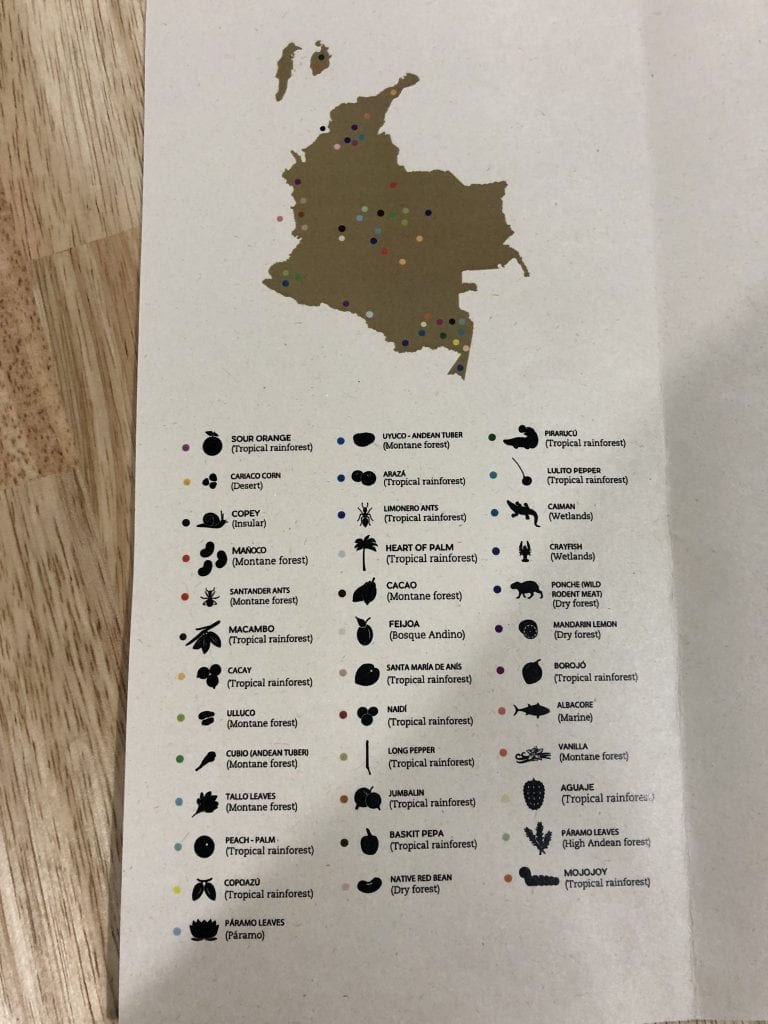

Ingredients featured in her dishes come from all corners of the country. In fact, on the left side of the menu, the restaurant provides a color-coded map, so guests are able to trace from where each dish comes — from the Andean forest to the Amazon rainforest to the coastal marine to the Colombian wetlands. For a restaurant that truly celebrates Colombian cuisine, plants, animals, and ingredients, it really is no wonder why it’s the 10th best restaurant in Latin America.

As we tasted some delicious pirarucu, a large freshwater fish native to the Amazon River basin, our waiter told us that the dish also featured cacay oil. He then emotionally described how the cacay tree’s very existence can help solve Colombia’s issues of poverty, deforestation, and coca cultivation (the plant used to make the active ingredient in cocaine).

How one plant could conceivably do all that obviously piqued my interest, and I did some investigating to learn about Kahai SAS, the first organization to industrialize the cacay tree for consumer use. The company is currently focused on growing production and sales of its cosmetic facial oil but has major plans of eventually turning to the food industry. Its key ingredient, the cacay nut, is not only an incredibly healthy, superfood with huge growth potential, but the oil that can be extracted from the nut is also more powerful and more beneficial than many beauty products currently on the market for people seeking wellness at home.

The more I learned from the company about the cacay tree, the more I began to realize that while we typically think of wellness tourism as something travelers pursue for their own purposes, their own desires and motivations, wellness tourism can also be used to make an impact on poorer regions of emerging economies. What could be better for people’s well-being than that?

Kahai is the first company to industrialize the cacay tree. Courtesy of Kahai SAS.

I sat down with Kahai co-founder Camilo Jaramillo, who, with his brother, Alberto, realized the potential of the cacay over 10 years ago. While the crop, found in Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, and Peru, has been used by indigenous people for centuries as an emollient and for healing burns and wounds, as well as studied for scientific purposes over the past 60 years, the tree is hard to find in the wild these days due to deforestation and has never been industrialized.

The oil that can be extracted from the cacay nut has 50 percent more Vitamin E and twice the amount of linoleic acid (Vitamin F) than argan oil and three times more retinol than rosehip oil. For those of you unfamiliar with key ingredients people look for in cosmetics, suffice to say this oil has a high concentration of vitamins that make it a better and more powerful facial oil than many other cosmetic items on the market for anti-aging, reducing dark spots, and improving hydration and elasticity of skin.

The cacay nut can not only be used to create an incredible cosmetic product, but can also benefit locals in high-conflict areas of Colombia; Courtesy of Kahai SAS.

The peel of the fruit can be used to feed cattle and for compost. The tree’s leaves, which fall seasonally, can help improve soil. The nut can be used in many types of foods, snack items, or nut milk. The nut meal leftover after extracting the oil can be used as a food supplement in items such as protein bars given its high level of protein, essential amino acids, and digestive properties. The list of benefits of this incredible nut goes on and on.

“We realized the potential, but we needed scale. First, we wanted to buy the harvest from peasants and communities in Colombia [which had the tree growing on their land],” Camilo Jaramillo explained. “But despite our efforts, this … was very difficult and expensive, and the fruit rots on the ground of the forest really fast … so we needed to move forward to plantations. We needed to domesticate the species.”

While Kahai is still buying the produce from around 300 families via its “wild production” category, the company now has 440 hectares of plantations in development which should help accelerate production. Through grafting, the company will be able to have trees start producing nuts in three to four years versus eight to 10.

Kahai’s process for increasing production of the cacay nut should ultimately lead to positive impacts for the country. Courtesy of Kahai SAS.

What’s even more compelling is that Kahai has developed social programs through NGOs and state supported social programs to help communities in high-conflict areas of Colombia learn how to plant the trees via subsidies and training and then sell the nuts back to Kahai. They’ve helped around 500 families in poorer regional areas (known as “departments”) such as Meta, Guaviare, Caquetá, Putumayo and Vaupés.

As a result, the cacay tree is a great candidate for reforestation and illicit crop substitution. It can help aide economic growth and development in areas affected by guerillas.

“The only reason they [these families] plant illicit crops is because there is a market for it, but they always ask, ‘You tell me what you will buy from me, and I will plant that. Give me an alternative,’” Jaramillo explained. “They don’t really like these illicit crops, because they’re the weakest link in the chain — whenever [authorities] pass in planes with pesticides like fumigation, they’re the ones that are affected, not the guerillas.”

“The guerillas just force them to plant the illicit crops, and they buy from them the produce,” Jaramillo went on to explain. “But … the guerillas threaten to kill them if they sell them elsewhere … This illicit crop — It’s an endless situation that moves from one place to another … It’s not sustainable.”

“Being able to live at peace is worth something [to these families],” Jaramillo stated. Plus, the cacay “is something you plant once, and you harvest it every year, so it generates a pension for these families for over 50 years. A hectare yields an average household income of more than the average minimum wage in Colombia for one month, and you don’t have to suffer with the illicit crops.”

Globally, Kahai is getting a lot of attention for not only what incredibly beneficial cosmetic products and nutritious food items can come from the cacay tree, but how it can be so helpful for poor communities in the high-conflict areas of Colombia. The company has won numerous sustainability awards, including winning Silver at in-Cosmetics Global 2017 for its Green Ingredient, the CBI Innovation Award in 2013 awarded in Paris, and an EPM Award for Sustainability in 2011.

Kahai also has a goal to reforest 5,000 hectares with cacay over the next six to seven years. “When using our products, you are [directly] helping us reforest 5,000 hectares with cacay in Colombia’s Amazon region, generating incomes for peasant and indigenous families within conflict zones.”

While the biggest [potential] market is the [food] nut industry, the company needs scale. As a result, “for the moment, we’ve been more focused on the cosmetic industry and selling the ingredient as an anti-aging active and also selling the finished product for skin and hair care,” Jaramillo stated.

Growing demand for Kahai’s facial oil appears to show no signs of stopping. “We’re exporting to over 12 countries, including the U.S., Canada, France, the U.K., Germany, Korea, Japan, and Australia.” The product is generating a lot of buzz as well, with beauty magazines, bloggers, and vloggers all talking about what an incredible product the facial oil is. I’d only expect it to grow from here.

Governments and Agencies Should Get More Involved With Promoting Products like the Cacay

Despite the numerous awards and recognition that Kahai is getting for its products, the government of Colombia is more supportive in talk than in terms of financial resources or promotion.

“One would think that being the largest biodiversity project in Colombia, we should get more attention from the government. But we don’t really get much support …,” Jaramillo stated. In fact, the company received the National Export Award last year in Colombia, which was actually handed over by the president, essentially only giving the company a pat on the back for what it’s trying to do.

“ProColombia is a government institution, and they have helped us, not much economically, but at least they like what we are doing. They invite us to business meetings or trade shows, but they lack resources to really boost the industry,” Jaramillo explained.

The company has been reliant on foreign investors and impact investment funds in order to support its future growth through its plantations which can, in turn, ultimately help families in need via social programs.

“Unfortunately, in Colombia, we are very creative, but in terms of innovation, sometimes we don’t believe in ourselves,” Jaramillo commented. “Innovation is to bring something that is proven elsewhere [in the world] and bring it to Colombia and implement it here. Sometimes, we do not believe we can create things that can compete worldwide.”

Bogotá: When Issues of Colombia Cannot be Hidden Beneath its Shiny, Modern Surface

I learned about Kahai and its facial oil using cacay while living in Colombia’s capital and largest city, Bogotá, for a month. Setting aside a history of considerable turmoil, Bogotá is now a sleek, modern metropolitan area, an economic powerhouse for the country, and a lovely city containing parks full of running dogs and owners, cute brunch spots, and craft beer bars. It offers easy access to different parts of Northern, Southern, and Central America and a pleasant way of life for its residents. In some ways, Bogotá makes it hard to believe there are larger underlying issues in broader Colombia.

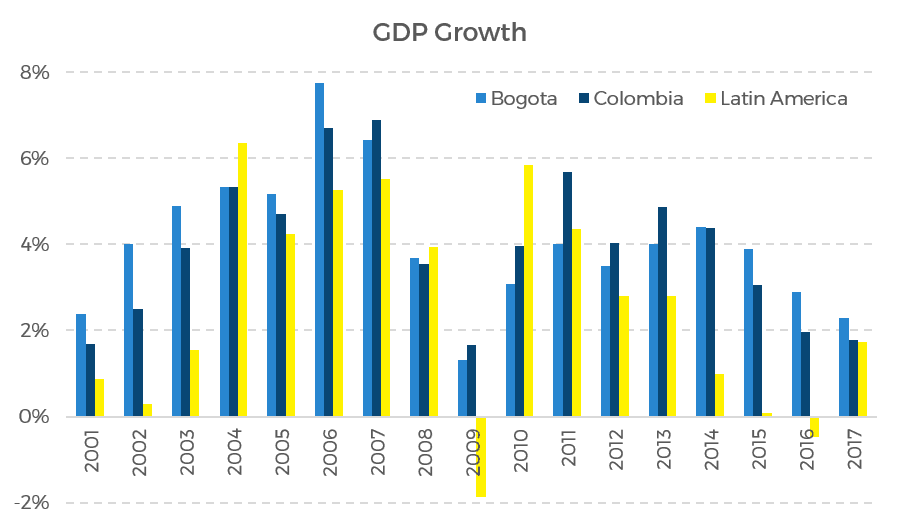

But Bogotá doesn’t tell the whole story of Colombia. From 2001 to 2017, Bogotá’s GDP growth has outpaced that of the country 10 times and Latin America 13 times. The capital city’s GDP currently makes up more than one-quarter of the entire country’s GDP, and its GDP per capita is around 60 percent higher than that of Colombia’s. As of 2017, Bogotá had a 49 percent share of all of Colombia’s medium to large businesses and accounted for 36 percent of the country’s international trade.

Source: World Bank, Colombia Reports

Source: World Bank, Colombia Reports

The larger issues of broader Colombia sometimes leak into wealthy Bogotá and are hard to ignore. Ten days before my fellow digital nomads and I traveled to Bogotá, we were informed that there was the worst terrorist attack the country had seen in 15 years. At least 20 people were killed in a car bombing at the General Santander Police Academy in Bogotá, the majority of whom were between the ages of 18 and 23. The attack was carried out by the National Liberation Army, a leftist guerilla group known for abductions, drug trafficking, mining illegally, and certain bombings and attacks, in response to peace talks with the government deteriorating.

It’s moments like these that shake locals and visitors to the core, making everyone question just how peaceful Bogotá and the overall country really is. Perhaps as an indicator, newly elected President Iván Duque’s approval ratings have recently been falling on heightened fears and security concerns. And it also cannot be ignored that coca, the plant used to make the active ingredient in cocaine, cultivation has reached an all-time high, up 11 percent in 2017 to 209,000 hectares according to the U.S. Office of National Drug Control Policy.

A local told my friends and me one night at our coworking space, “it’s super overwhelming … A few weeks ago, our president signed an order which said that the Ministry of Defense is allowed to give civilian populations weapons if they deem it appropriate. That’s how — like — vague it was. The last time they did this it was the worst paramilitary raid we’d had in a long time. It’s a scary time.”

Sometimes issues of Colombia’s ongoing corruption, continuing issues with guerilla groups, wealth inequality among the different regions of the country, and the ramifications of the continually growing, illegal drug trade emerge from beneath Bogota’s shiny, outer surface.

I recognize the Colombian government may feel like it has bigger fish to fry than making sure that small companies like Kahai get the appropriate funding and promotion that they need. But it is exactly supporting these types of companies that can help tourists be better tourists, help local incomes improve, help emerging economies develop, and, in Kahai’s case, help stop the spread of illicit crop cultivation.

And the cacay tree is just one example of a product made in Colombia that not only can compete worldwide, but also can be so beneficial to the country’s future development. I took a class one night on traditional craft making, known as “artesanías en mostacilla,” and made a beaded bracelet using the peyote technique. We learned how crafts have been used to economically support many of Colombia’s indigenous communities for hundreds of years. However, these ethnic groups, of which Colombia has around 80 recognized groups and many more unrecognized, lack the resources or support to control or regulate the industry. As a result, many tourists are buying counterfeit products or being overcharged or scammed.

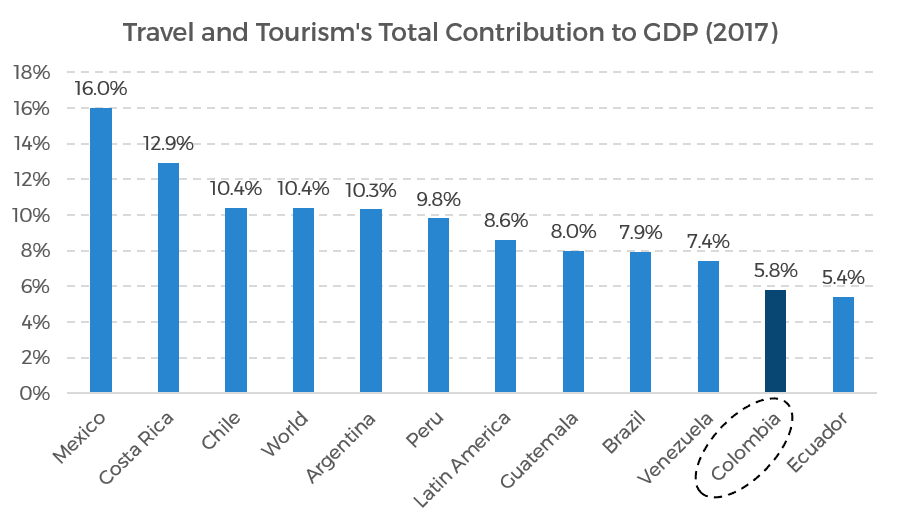

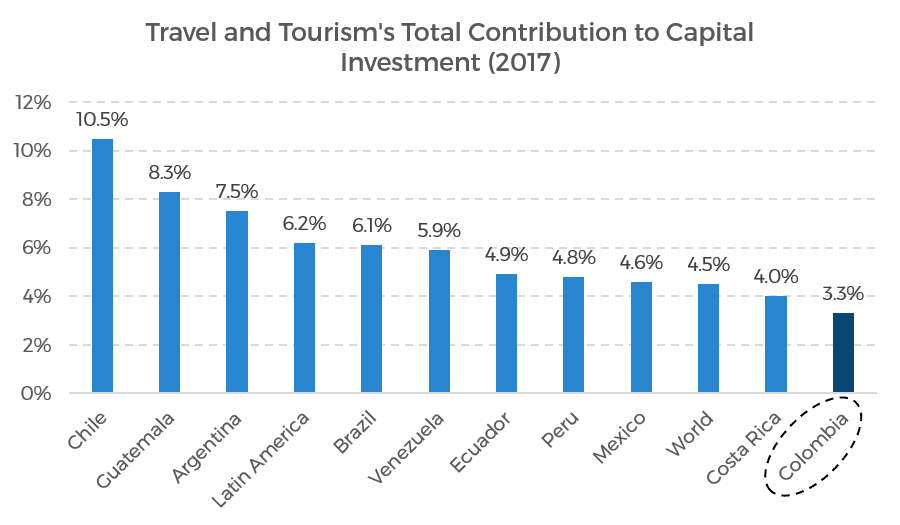

Currently, travel and tourism directly and indirectly make up under six percent of Colombia’s GDP. The average for Latin America is almost nine percent. Travel and tourism also make up under six percent of Colombia’s total employment, whereas the average for Latin America is just under eight percent. Out of all the capital investment that Colombia attracted last year, travel and tourism made up only three percent. The average for Latin America was above six percent.

Source: WTTC

Source: WTTC

While other countries face issues of overtourism, Colombia clearly has a ton of opportunity to use travel and tourism to better serve its economy, its companies, and its people.

Learning to Be, Not Just a Better Tourist, But a Better Global Citizen

But, if the government isn’t going to support small, but highly impactful, companies, we, as tourists, still can.

Tourism positively impacts economies when travelers support local businesses, local culture, and local arts that can directly benefit those in need. Tourism hurts when travelers go to key areas at peak time periods or flood cities that don’t have appropriate infrastructure.

In Bogotá, it’s hard to feel like a tourist. The capital city, located in essentially the center of the country, is home to over 8 million people. For reference, New York City has a population of around 8.6 million, but while New York City spans 303 square miles, Bogotá is twice the size at 613 square miles.

The view from the top of Monserrate in Bogotá demonstrates just how massive the city is; Photographer: Barbra Araujo

Bogotá is so massive that, other than “touristy areas” such as the Plaza de Bolívar and museums near La Candelaria, a foreigner can essentially blend in with the hordes of smartly dressed Colombians out for a beer after work. While some travelers call Bogotá “just another city,” I, on the other hand, felt like I could easily slip into living a normal life in the city without feeling like a tourist sticking out like a sore thumb.

I got up and went to work every day at a nearby WeWork or cafe. I went running in Parque El Virrey (albeit rarely, and only when my lungs would allow it — Bogotá is at an altitude of 2,640 meters above sea level). I drank Colombian coffee essentially every day. I went to the Andino Shopping Mall located in Bogotá’s trendy Zona Rosa district with some friends for some retail therapy and to purchase Kahai Oil. I learned the differences between the bachata, merengue, and salsa at Andres DC via the help of locals. I simply lived, focused on my own happiness and well-being.

Before my time in Bogotá, I had never really thought about how I could have such a directly beneficial impact on a country simply by living and buying products that I enjoy and love. Learning about cacay tree and indigenous crafts made me recognize that, even from shiny Bogotá, you can contribute dollars into poorer cities and regions that normally don’t get government, financial, or promotional support.

Maybe someday being a tourist will become less about being a foreigner in a foreign country and more about being a better global citizen. Maybe, when it comes to travel, we’ll think about how we can better help the world grow and improve by buying products that directly benefit people who need it and investing in new projects and opportunities that help emerging economies grow.

The Daily Newsletter

Our daily coverage of the global travel industry. Written by editors and analysts from across Skift’s brands.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: bogota, climate change, colombia, data and discovery, skift on the road, south america, sustainability, tourism, wellness

Photo credit: The cacay nut not only leads to an incredible cosmetic product, but can also benefit locals in high-conflict areas of Colombia. Courtesy of Kahai SAS