Skift Take

Medellin has gone through an incredible transformation over the past 30 years, but large issues still remain prevalent. As the city figures out the right story it wants to tell, its "fake it ‘til you make it" strategy somehow works — speaking to the resilience of many developing economies that are navigating histories of crime, corruption, and violence and still figuring out how to position themselves as destinations.

Skift Senior Research Analyst Rebecca Stone is traveling the globe over the next year as part of Remote Year, a program that brings together working professionals to travel, live, and work remotely. She'll spend a month in 12 cities around the world that include Cape Town, Lisbon, Valencia, Sofia, Hanoi, Chiang Mai, Kyoto, Kuala Lumpur, Lima, Medellin, Bogotà, and Mexico City. And every month she'll take you along for part of the journey with a feature about her observations based on firsthand reporting and data about the changing travel industry. She'll do the jet lag. All you have to do is kick back and enjoy her compelling dispatches.

Medellin, Colombia. Pablo Escobar. Drug cartels. Violence. Crime. Previous title-holder of “the world’s most dangerous city.”

Medellin, Colombia. Beautiful. “City of Eternal Spring.” Trendy. Coffee. Avocado toast. “Most innovative city in the world.”

Within an hour of arriving to Medellin, located in the Antioquia region in a lovely valley surrounded by gorgeous mountains in the northwestern part of Colombia, I was eating street tacos with friends at a cute, outdoor joint ironically named Criminal Taqueria that reminded me of New York’s trendy Tacombi.

Reminders of “You need to be careful — Medellin is really dangerous” from people back home quickly evaporated as my friends and I gaped over how chic Poblado, a popular residential and commercial neighborhood in Medellin, was. We were surrounded by cool boutiques and restaurants blasting music just begging to be checked out. As we chatted, Colombian women more stylish than many New Yorkers strolled by, and digital nomads typed away on laptops next to fruit juices at nearby cafes.

This wasn’t at all what I thought Medellin was going to look like.

Criminal Taqueria, a local taco joint in the Poblado area, became a regular spot for us digital nomads.

Medellin has gone through an incredible transformation over the past 30 years. Some areas such as Poblado make it difficult to believe the city was ever the murder capital of the world driven by the violence of its illegal drug trade. The metro, of which the people of Medellin are incredibly proud, gives Singapore’s a run for its money in terms of cleanliness and pleasantness. The city continues to win awards for the dramatic urban development it has gone through, most recently being named Latin America’s representative as a Center for the Fourth Industrial Revolution at the World Economic Forum in Davos.

Other parts of Medellin, however, are still very much developing and tell a very different story of how the city’s challenging past continues to impact its present. Medellin’s government, private sector, and academic sector are working diligently together to tell the right story via education, social programs, infrastructure development, and other investments. In some ways, these strategies are working. Medellin continues to develop and is improving economically and socially. In other ways, the changes being made feel like prettily decorated Band-Aids covering up much larger issues.

Remembering Medellin’s Difficult, Tumultuous Past

Medellin was founded in 1616 by Spaniards likely fleeing the Inquisition and, obviously, in search of gold (they were disappointed). But the lovely city remained essentially hidden and isolated by the mountains that surround it for centuries until the hum of transportation began to connect it to the outside world and the buzz generated by coffee put it on the map in the 20th century.

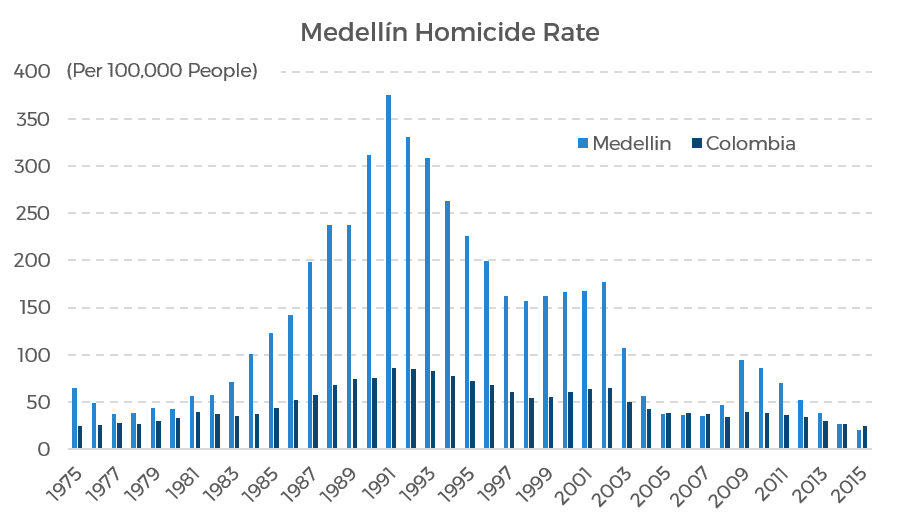

Nevertheless, most people think of a different history when it comes to Medellin — one either learned from the media or remembered by living it back then. Medellin became the cocaine capital of the world in the 1980s under the leadership of drug lord Pablo Escobar. Violence and crime associated with the drug trade spilled out into the streets, with the homicide rate reaching unruly highs. It is estimated that Pablo Escobar’s cocaine cartel controlled 80 percent of the world’s cocaine market and brought in approximately $70 million a day at the height of his power in the mid-1980s, making him one of the richest people in the world at the time. He and the people who worked for him were responsible for the deaths of thousands of people — from journalists, to politicians (including three Colombian Presidential candidates), to innocent civilians. No one was able to hide from the terrors associated with the time.

After surrendering in return for Colombia repealing extradition (He was pretty wanted in the U.S. if you can imagine), Escobar remained in a self-designed prison — in reality a luxury mansion — located in the hills outside Medellin called “La Catedral.” He did later “escape,” but was eventually found and killed by authorities in 1993.

My friends and I hiked to La Catedral, Pablo Escobar’s former “prison,” our first weekend in Medellin.

The chaos continued even after Escobar’s death without competent leadership to restore some sense of order. The drug business split into different groups with different alliances, but with the same willingness to commit crimes in the streets. The homicides continued, including the death of Colombian soccer star, Andres Escobar (no relation to Pablo Escobar), whose murder over mistakenly sending the ball into Colombia’s own goal during a game against the U.S. continues to be linked to the drug trade today.

Álvaro Uribe, who served as Colombian president from 2002 to 2010, is sometimes cited as helping to calm the storm in Medellin. He swiftly used military force to push back on and demobilize paramilitaries and guerilla groups such as FARC (The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia—People’s Army), a guerilla movement deemed a terrorist organization by the government, and the AUC (The United Self-Defenders of Colombia), a paramilitary and drug trafficking group.

As murder rates began to fall, Medellin, Colombia, was finally able to begin a new chapter.

Tale of One City: Look How Far Medellin Has Come

The government did not just fight back via enforcing the illegality of drug trafficking and demobilizing violent groups, but has also fought back via investment in social programs and infrastructure development.

“The government has driven a lot of the change, and they have put [in] a lot of investment,” noted Ana María Moreno, executive director of Greater Medellin Convention & Visitors Bureau which helps to promote the city for business tourism and events. “They have invested in social programs. For example, in the sector of education, we have a lot of stipendiums [scholarships] for people to go and study in the universities so that when they finish school they have more education, and they can get employment … [And] the local administration has a program with the schools” to keep kids from dropping out.

“Most of the investment in terms of infrastructure has been in the poorest neighborhoods, or the people with fewer economic resources,” she went on to say. “They have put a lot of effort in terms of building libraries, transportation methods, [and] in every neighborhood they [now have] a big soccer field.”

The development of better transportation systems in Medellin certainly sets the city apart from other destinations. The Medellin Metro began running in 1995, for the first time lifting borders between rich and poor areas of the city and giving access to everyone.

The first metrocable (Line K to Santo Domingo) opened in 2004, giving 230,000 inhabitants the ability to easily access Medellin proper (what previously would have been a two-hour journey) via cable car. Another cable car line connects Santo Domingo to Parque Arvi, an ecological nature preserve enjoyed by tourists and paisas (locals to the Antioquia region) alike.

“Right now you can live on the north side on the top of the hill, [and] you can use the metro system and work on the south side of the city,” Moreno noted. “All this innovation has impacted the society, and how we mix with each other in the city … You can be more connected.”

Approximately 43,000 people use the MetroCable lines per day as of 2013.

A 384-meter escalator divided into six sections was planted in the center of Comuna 13 (a “formerly“ dangerous neighborhood once home to violent guerillas and drug traffickers) in 2011, transforming the area into a tourist attraction by day and also making it much easier for its inhabitants to trek up and down the steep hillside.

Comuna 13, once a dangerous, difficult place to get to, is now a vibrant and easily accessible area by day; Photographer: Matt Oney

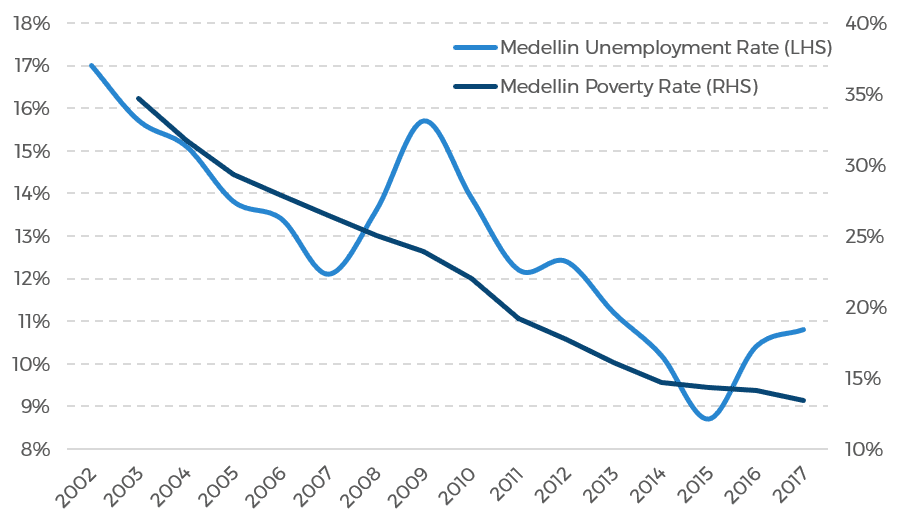

Investment in social programs and better infrastructure in high-crime areas, combined with increasing the city’s police force helped to rebuild trust between paisas in the city and the authorities. These improvements also created a new foundation on which Medellin’s economy could grow. And, for the most part, Medellin’s economy has steadily improved since the 1990s. Employment continues to rise, and poverty levels are declining. Colombia in general has seen solid GDP growth, outside of a recession in 1999 driven by the rapid increase in public expenditures and private sector indebtedness and more recently driven by low commodity prices, declines in the mining sector, and constrained domestic demand.

Source: Colombia Reports Data, National Administrative Department of Statistics

Source: International Monetary Fund

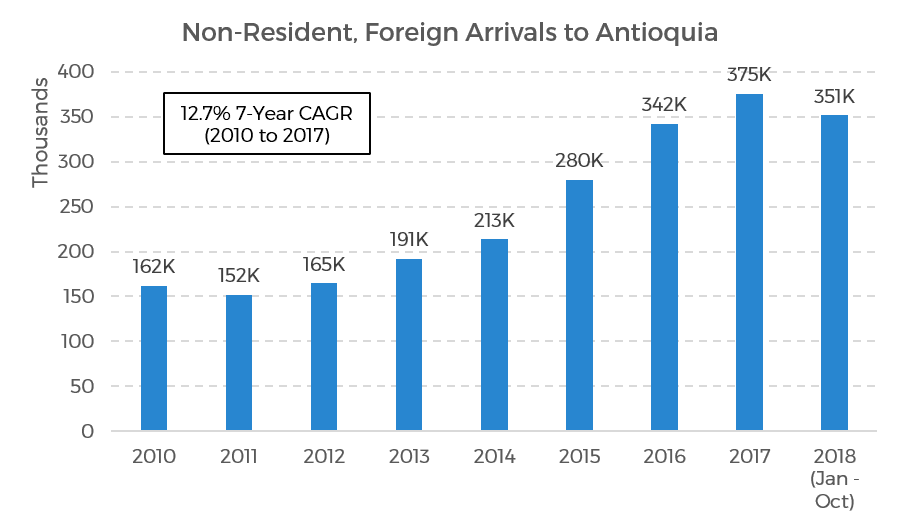

The economic improvements and increasing trust that Medellin has seen has encouraged tourists and businesses to come check out this lovely city. Non-resident, foreign visitors to the Antioquia region (of which Medellin is the largest city), reached almost 375,000 people in 2017, representing a 12.7 percent compounded annual growth rate over 2010. For reference, foreign arrivals to Medellin averaged 75 percent of foreign arrivals to Antioquia from 2014 to 2017. There were only about five hostels catering to tourists in Medellin in 2010. Now that number is around 150.

Source: Center of Tourism Information for Colombia

Nomad List, a database of more than 1,200 cities, ranks Medellin the fifth best city in the entire world for digital nomads and remote workers due to its relatively cheap cost of living, great startup scene, walkability, and tons of places to work. From Pergamino to Café Velvet to Betty’s Bowls to Selina CoWork, the list of places you can get work done from is pretty much endless. The city tops many lists on the best places to retire outside of the U.S. given how cheap it is and its year-round spring-like weather.

Pergamino was one of the many great places to get work done in Medellin; Photographer: Annika Wikberg

“Companies are [also] coming here to put their base or offices, because they find good talent, it’s cheap, and … because of the quality of life, so that has helped a lot,” Moreno highlighted. “There a lot of tax benefits for the people who want to come and invest in Medellin … Also because of the strategic location of Colombia. There are a lot of companies that want to come here and put their South American headquarters here, because we’re close to America, we are on the same time zone, etc.”

Medellin has a center of excellence for artificial intelligence to help create better jobs and increase innovation, was selected by UNESCO to host the International Conference on Learning Cities in 2019 given its dedication to improving education, and, as of 2017, only had 300 fewer startups than the capital city, Bogota. Last year, Greater Medellin Convention & Visitors Bureau helped bring in or provided support to 100 events in the city. Organizations such as Ruta N, Parque del Emprendimiento, ACI Medellín are all dedicated to enhancing Medellin via innovation, entrepreneurship, and increased investment in the city on a national and international level.

“Medellin has started to change the perspective of being an industrial city to being a knowledge-based economy,” Moreno explained. “The government, the private sector, and the academic sector got together to develop a vision of how we want Medellin to be in 10, 15 years and [to help] implement innovation, science, and technology.”

Clearly all stakeholders are dedicated to creating a better Medellin. The city has a Science, Technology and Innovation Plan in Medellin 2011-2021, as well as a Tourism Strategy Plan for Medellin 2018 to 2024.

“There are a lot of points that have positioned Medellin as a city that is on the rise, and people are curious about coming here,” Moreno said. “People like to see the transformation … When they go to Comuna 13, they go to the different neighborhoods, and they see how, through education, through social programs, through art, through culture, how it has impacted the development of the society. It’s something that people cannot believe … The transformation is one of the major hooks or differentiators of the city.”

Tale of the Other City: A Well-Developed Façade

However, there’s another story of Medellin to tell.

I met straight shooter Chris Cajoleas, owner of Tejo in Medellin, while playing Tejo with some fellow digital nomads one night. Tejo, which is the national sport of Colombia (not soccer contrary to popular belief), is essentially like the lawn game cornhole, but with mud and explosives, which makes it infinitely more exciting.

‘

The following week, I met up with Cajoleas for breakfast in Pobaldo at his old restaurant, the Flip Flop Sandwich Shop. Regarding the reasons why he moved to Medellin from the U.S. almost 10 years ago, he told me, “For the first time in my adult life, I was relaxed … This was the first place I had ever been where I didn’t feel that necessity to be worried.” As we chatted, he’d pause to greet and talk with the people in the restaurant – he knew everyone there.

As we talked, Cajoleas started to point out to me that not everything is as it seems in Medellin.

“Tourists want to go do stupid stuff like go visit Comuna 13, and I say that, for me, as someone who lives here … when you go to Comuna 13, you’re not seeing the real life. Meaning when you go away and the nighttime comes, that [neighborhood] goes back to being a place that you don’t want to be … It’s still a dangerous place.”

I responded that I probably could have guessed that and then asked him about Poblado instead. In trendy Poblado, I felt completely at home — there was avocado toast, mango juice, and Wi-Fi available on every corner.

“In Poblado, people are definitely spending money to make their bars and restaurants look good. I don’t think they’re necessarily dressing it up to make it look safe … [It’s just that] Colombians are all about aesthetics. Just look at the women,” referring to the high levels of plastic surgery in the city. “What you don’t know … is that a lot of the businesses here [in Poblado] are money laundering fronts.”

Over the course of our conversation, we peeled back the layers of Medellin’s intricate façade. He told me stories that had occurred within a couple blocks of where we were sitting — a professor poisoned by a group of women in late 2018; a body of a man found in a suitcase in Parque Lleras, a park with a lot of lively bars and restaurants in Poblado; in early 2018, two tourists drugged with scopolamine and robbed in 2017, one of which died as a result.

I had to admit that I already knew about scopolamine, commonly known as Devil’s Breath. I knew two digital nomads who were roofied and robbed at a bar one night out with a couple Colombian women just the weekend before. I was having difficulties rationalizing how nice Poblado was, how much I could picture myself living there, and the realities of what was actually going on beneath the surface in Medellin.

“What I tell guys is that you need to know the rules of the playground in which you are playing in. Too many people try to make this their playground,” Cajoleas said. “Anybody who comes here just needs to be aware that they are not at home.”

The reality is Medellin is a thriving city for whatever your worst vices are — sex tourism and prostitution are incredibly prevalent, and drugs are readily available and easily accessible. Whatever you are into, no matter how dark or grotesque or illegal, you can probably find it in lovely, little Medellin.

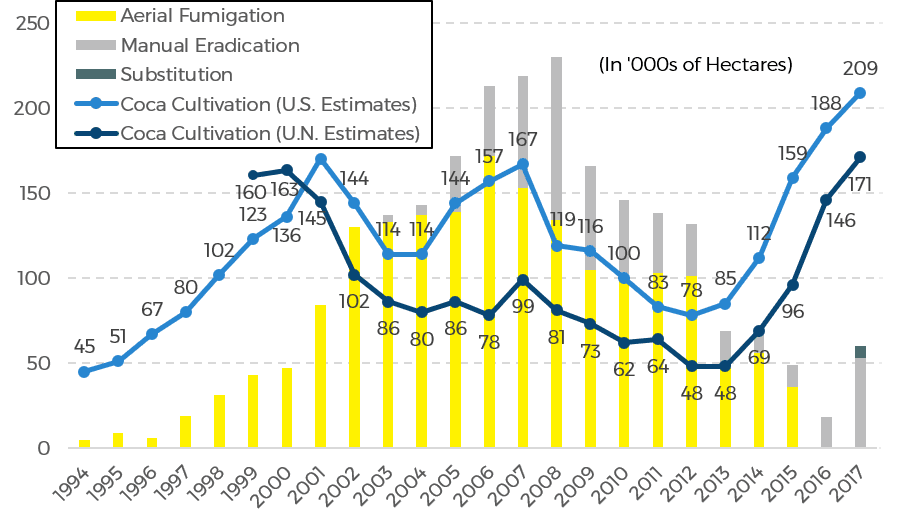

In fact, coca, the plant used to make the active ingredient in cocaine, cultivation has reached an all-time high, up 11 percent in 2017 to 209,000 hectares according to the U.S. Office of National Drug Control Policy. For reference, in 1994, one year after Pablo Escobar’s death, it is estimated that there were 45,000 hectares used for coca cultivation. Aerial fumigation was halted in 2015 due to it having very harmful side effects, and clearly the cartels have continued to find ways to smuggle drugs to prime markets, particularly the U.S. About 90 percent of the cocaine seized in the U.S. in 2015 was from Colombia, and it appears most drugs are getting into the U.S. through legal ports of entry.

The truth of the matter is, although the violence in the time of Pablo Escobar has long been removed from the streets of Medellin, the drug trade is really stronger than ever.

Source: U.S. Department of State, White House, UNODC, EL Tiempo, Adam Isacson (WOLA Director for Defense Oversight)’s Twitter.

In addition, despite all the economic improvements Medellin has made, wealth inequality remains a huge issue. The wealthiest one percent in Colombia control 40 percent of the nation’s wealth (Colombia ranked 6th out of 40 countries ranked in terms of wealth inequality). Monthly minimum wages in Medellin are around $260. For reference, average one- to three-bedroom apartments range $250 to $430 per month.

Source: Credit Suisse, Research Institute, Global Wealth Databook, 2018

Source: Minimum Wage Colombia, Numbeo

The more I learned about Medellin during my time there, the more I couldn’t deny that aspects of the city’s incredible transformation were really just decorative Band-Aids covering up much, much larger issues.

“Look, the only way you ever fix things is with education and money, and it’s hard when the government isn’t in control … I feel like the people excelling will always be the same, and the others [the poor] will be the same,” Cajoleas commented. “I think it’ll keep going the way it’s going, because there will always be a demand for drugs, there will always be a demand for laundering money … I just don’t see anything ever changing … I think it’ll be the same, just more of the same.”

Fake It, ‘Til You Make It: Learning to Tell the Right Story

In some ways, Medellin is still figuring out the story it wants to tell.

“We have had very hard times, and we still have some challenges [with] safety, criminality, all the drug smuggling, so there are problems in the city,” Moreno told me.

Some paisas remember how Pablo Escobar changed the lives of the poor for the better. He built homes for the homeless and had soccer fields added for recreation. On the other hand, some locals remember that time period in terror and won’t even say his name out loud.

Add into the mix sources such as Netflix and other media that glorify him and the narcos, romanticizing a violent, illegal, underground industry. “Some people have [only heard] the story of the city that is told by the TV,” Moreno commented. “[And] people cannot differentiate if it [the story being told by the media] is real or not.”

Some tourists come to Medellin specifically to partake in the dark corners of the city. But some tourists come to Medellin to learn and better understand Medellin’s difficult history. They want to hear the real story.

“As a city, we do not want to pretend that it [Medellin’s violent history] didn’t happen,” Moreno explained. “What we are doing is trying to reconstruct that story in a very responsible way.”

What is really cool and exciting to see is that everyone is working together and focused on the issue — the public sector, private sector, and academic sector. “We, as part of this ecosystem, are conscious about it, and we are willing and putting some effort to it,” Moreno stated.

Currently, the story gets somewhat lost in all of the green juices, goat cheese salads, and trendy restaurants blasting music.

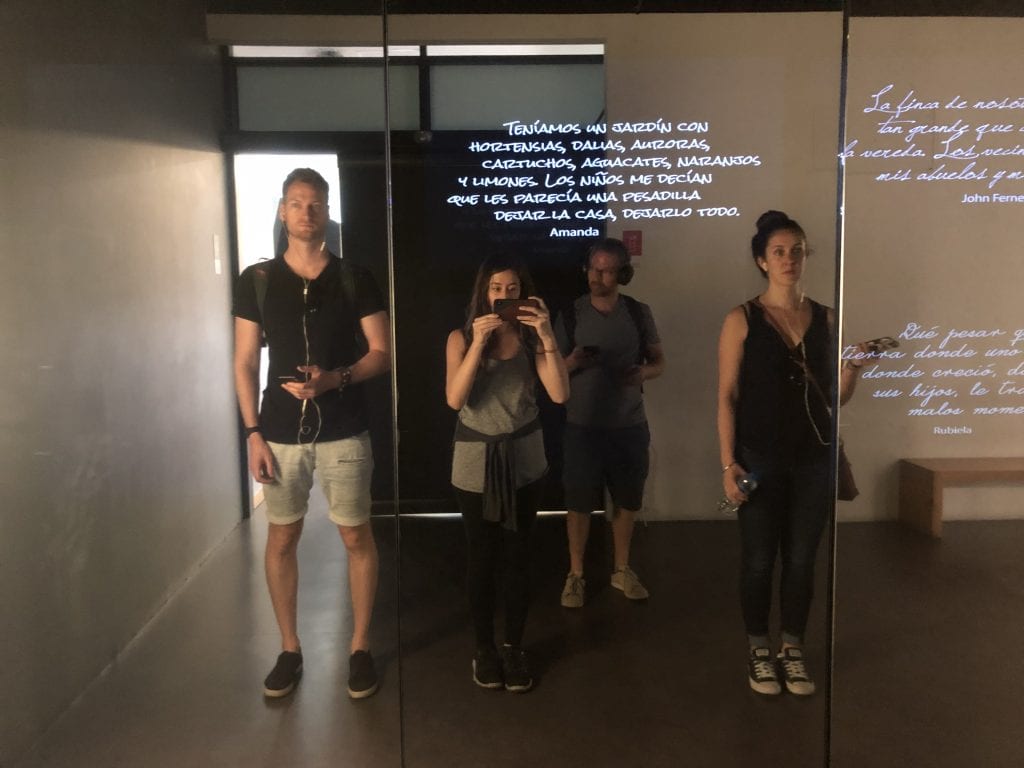

However, in other places, the story rings loud and clear. One of immense pain, but also of hope, of determination, and of resilience. At Museo Casa de la Memoria (House of Memory Museum), you learn about the history and impact of the drug trade in Colombia through the eyes and memories of the people who lived during that time. The description of the exposition, Medellin, memories of violence and resistance, inside the museum reads: “Like all stories, it is incomplete, subjective and imperfect. But it is a narrative of various voices … We know that there are as many museums as visitors and interpretations. We hope that this space provokes reflection, ideas, and emotions; that it moves you to be a part of the construction of a new proposal for society. In the end, you are also part of this history.”

The city also has plans to demolish Pablo Escobar’s former home later this month and turn the area into a park and memorial dedicated to victims. Medellin is clearly craving consistency, stability, and peace.

“We have a strategy … [to tell] a story of the city where the real heroes are the heroes, not the narcos, not the bad people,” Moreno explained. “Because people are coming here to hear the story, so right now what we are doing now, more than avoiding the story, is … [developing] a solid story where the heroes, the people who fought against the narcos, are put in their [rightful] place.”

As I wrestled with the complexities of Medellin, the struggles it has gone through, and the different views that paisas have on its history, I thought about how change cannot be made overnight. You can’t just beautify an ugly duckling and call it a pageant winner. It has to grow into a beautiful swan. And that simply takes time.

However, and in the meantime, I’m not sure there’s anything wrong with Medellin’s “fake it ‘till you make it” strategy. The city is remaining focused, staying the course, and trying to be better each day.

The majority of cities in emerging markets are working on developing economically and socially, navigating histories of crime, corruption, and violence, and determining how to position themselves as destinations for travelers to come, feel safe, and learn. While all of that will have to take time, developing and telling the right story, the story they want to tell, will be what travelers ultimately remember.

The Daily Newsletter

Our daily coverage of the global travel industry. Written by editors and analysts from across Skift’s brands.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: climate change, colombia, data and discovery, destination management, economic development, emerging economies, medellin, skift on the road, skift research, south america, sustainability

Photo credit: Medellin, Colombia, has been through a lot, and, while it certainly has a lot further to go, the city is making progress on how to tackle large issues, market itself as a destination, and tell the story it wants to tell. Rafat Ali / Skift