How Travel Media Missed the Digital Leap

How we discover, dream, and plan vacations has changed radically as print has given way to digital and desktop gave way to mobile. Lost in much of this are the gatekeepers — legacy print brands on newsstands and in bookstores — which were slow to adapt to the changing media landscape.

Skift Senior Writer Andrew Sheivachman spent the last month speaking with publishing experts, editors-in-chief, and industry players for a deep dive into why things happened this way and how brands are pushing forward to succeed in this new environment. — Jason Clampet, Editor-in-Chief

Two decades ago, travelers had limited choices when they wanted to research their upcoming vacation. They could open their local newspaper’s travel section, buy a glossy magazine, call a travel agent, request brochures from a resort, or even experiment on their dial-up modems with slow and confusing online booking tools.

Travel magazines, newspaper travel sections, and printed guidebooks represented the most trusted and popular way for travelers to find inspiration for their upcoming vacations and bring crucial information on the road during a trip.

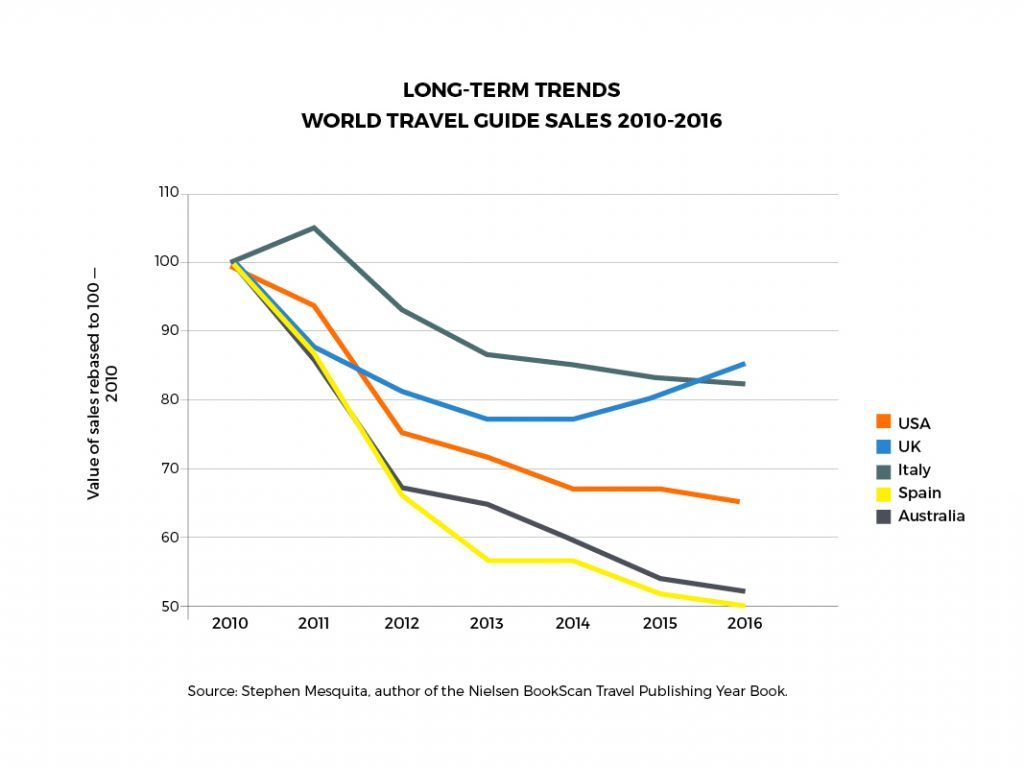

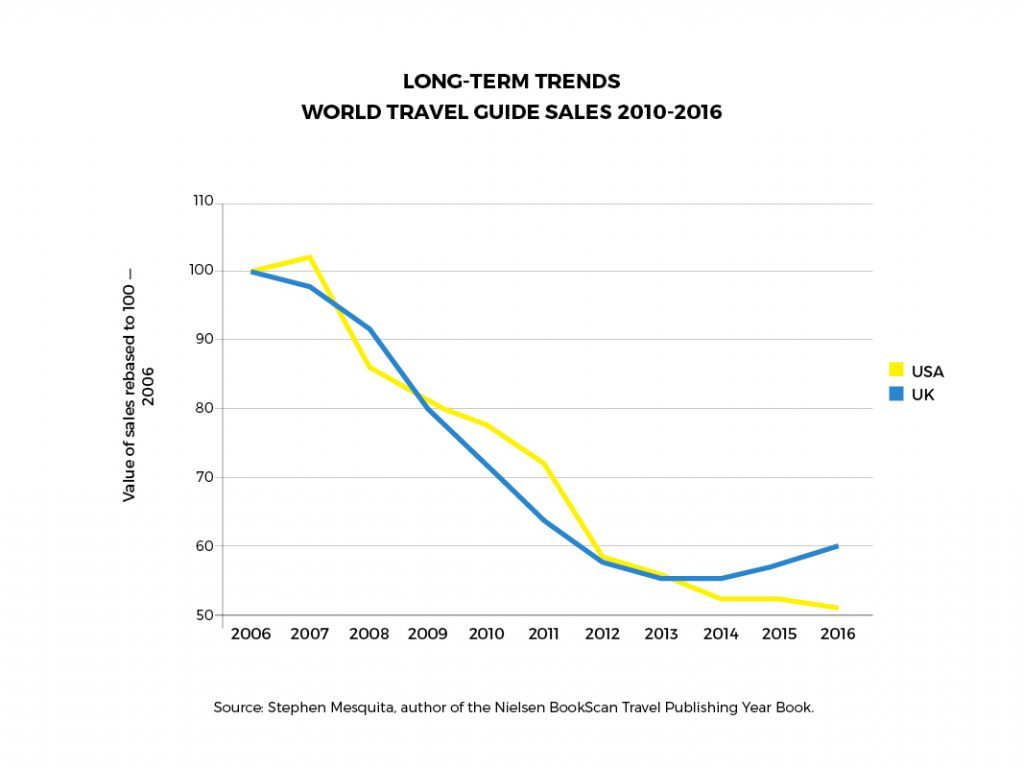

Over the last 10 years travel magazines have shrunk in size while the global guidebook market has been halved as consumers have moved to websites and apps for their travel fix. Today, consumers can turn to TripAdvisor, Google, Yelp, online forums, social media, YouTube, and countless other content sources.

Consumer travel brands have had trouble cracking the digital space, for reasons both institutional and determined by the shifting media marketplace.

Print consumer media, in particular, has been most powerfully disrupted. As legacy consumer travel magazines withered from a lack of advertising, and staff cutbacks in the wake of the Great Recession, mobile and digital content became more popular among consumers. These brands did a poor job of appealing to readers on new platforms, despite their outsized influence and recognition among travelers.

Why have consumer travel media brands had so much trouble evolving? Skift spoke to editors, marketers, and travel media experts about the past, and future, of print travel media’s digital evolution.

Put simply, print brands were slow to adapt to the digital media ecosystem in ways that other media companies, particularly in the finance and general interest areas, were not. And the effect of abundant, free online content, particularly from sites like TripAdvisor, helped change the behavior of travel consumers while print brands struggled to move online.

“I don't actually think [print travel media] ceded [authority] to TripAdvisor,” said Barbara Messing, TripAdvisor’s chief marketing officer. “They ceded it to the people, the authority of millions of travelers who post their opinions on TripAdvisor. We create the platform so that people could share. That is the power of TripAdvisor. It's the community that is our power, not necessarily the corporate entity, and the fact that we created a platform where it was really easy to share, really easy to post photos, and we created it in such a way that people could find what they were looking for.“

Print travel media has gone digital, but not without growing pains. How do you reinvent a business model that has existed for decades, while wrestling with the constant churn and change in the digital media marketplace?

"The single biggest challenge that we face is exactly that,” said Nathan Lump, editor in chief of Travel + Leisure. “And I think successful digital operations are very clear about what they don't do as well as what they do. There's essentially a well that has no bottom and so you can't fill it with everything. You have to be really purposeful about what you're making.”

The Case of Condé Nast Traveler

It can be instructive to look back to the mid-2000s, when it became clear that digital disruption was changing the business model for media companies. Some, like The New York Times, were quick to adapt to the digital space, while others lagged behind. Magazines, in particular, had trouble conceiving of a way to move away from selling expensive print advertising space. Why sacrifice such a lucrative source of revenue, even as readership began to decrease?

At Condé Nast, perhaps the world’s most preeminent media company, the question of what to do with industry leader Condé Nast Traveler was a challenge. First introduced in 1987, Condé Nast Traveler became one of the most visible brands in travel.

It became clear, however, that online booking and travel research was becoming important for consumers in the late 1990s. So Condé Nast launched a new brand, Concierge.com, to house online travel content and sell vacations online through a partnership with Expedia. The editorial teams of Condé Nast Traveler and Concierge.com were completely separate at first.

“Condé Nast had decided at some point that to test the digital audience, they really needed to create separate brands from the magazine brand,” said Peter Frank, who served as editor-in-chief of Concierge.com from October 2005 to December 2009. “So Epicurious became a food brand, and Style.com became fashion. Those had varying degrees of success and attraction for an audience by creating their own distinct personality vis-a-vis their print counterparts. While there are benefits of doing it that way, there are also a lot of disadvantages, mostly that you kept your print teams in their own swim lane and your digital teams in their own swim lane and you weren't evolving either towards the inevitable future that most of us saw that, you know, print and digital would have to work together.

“At Concierge.com, that was a separate building, a separate business unit, and separate reporting structure, but we shared real estate on the web and that led to inevitable tension.”

It was clear to writers and editors at both brands that there had to be more collaboration between the two sites. Condé Nast leadership, however, was more hesitant and slowed many efforts to better integrate content between them. The scale wasn’t there on the digital side, so it made no sense to move resources towards the digital space when the print Condé Nast Traveler magazine paid the bills through print advertising and advertorial content.

“By 2006 it had become clear that there had to be more synergy between the print and online products,” said Wendy Perrin. “In 2006 I was asked to start writing a blog, The Perrin Post, so that print readers could interact with me online. But Condé Nast Traveler did not have its own website, so my blog was published on Concierge.com—which is where all Condé Nast Traveler content was published. Concierge.com was run by a different staff, in a different building, and it was endlessly frustrating that we had so little control over our online presence.”

While Condé Nast’s travel content was siloed, TripAdvisor had gained traction among consumers looking for travel information. In 2004, TripAdvisor was already the seventh most visited travel site on the web according to IAC, which acquired it that year.

In May 2007, TripAdvisor acquired Smarter Travel Media and The Independent Traveler, bringing a variety of niche media properties under its corporate umbrella. By May 2011, when TripAdvisor was spun off from Expedia, it was serving 50 million unique users a month on its site.

While the Condé Nast Traveler and Concierge.com teams would grow more integrated over time, the economic crisis of 2008 caused major headaches for media companies looking to experiment online. Condé Nast would shutter four magazines and lay off more than 120 workers, as well as reorganizing the staff of its travel brands. Fewer magazines means fewer ad pages, and the need for fewer staff members.

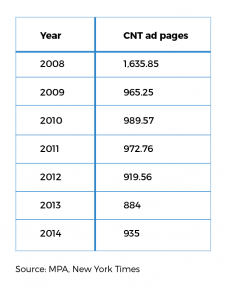

According to The New York Times, Traveler’s ad pages dropped 41 percent through the first eight months of 2009, making it one of the hardest hit magazines in Condé Nast’s stable. Overall, Condé Nast lost about a third of its overall ad pages in 2009.

Condé Nast Traveler’s print ad revenue did rebound, beginning to trickle upwards in 2010, with up and down years followed by solid three to five percent growth beginning in 2013.

What followed is what would become a familiar scene in the media world: shrinking issues, less ad revenue, staff layoffs, and eventually an editorially diminished print product. At the same time that Condé Nast Traveler would have been served by a robust online presence, it simply did not have the resources to develop one.

Frank worked on the print staff of the magazine in the 1990s, and saw the struggles as the publication half-heartedly pivoted to the web. Today, Frank works as a consultant with travel brands developing content for their brand-owned channels.

“Condé Nast Traveler was the authority in travel; we were the journal,” said Frank. “We were the ones who were going out there, saying, ‘Here's what you really need to see, this is what [these destinations] are really like. We're going to tell you the unbiased truth. We're going to take down the sacred cows of the industry because we can and because we should.’ And we got a huge amount of accolades for that. We won awards, we thought, and we were a very successful magazine. But that base in journalism no longer resides in print, that kind of authority for the media no longer resides in magazines, if it resides anywhere.”

By the time Condé Nast Traveler began a digital revamp in 2013, when new editor-in-chief Pilar Guzmán took over, travelers had already been looking elsewhere for years. Eventually, the Concierge.com brand would be completely retired by the company.

“In terms of looking back I think it was really about doing a bit more of a broader goal search about what the brand could stand for,” said Guzmán. “How the mission of the brand would then translate to the different channels, not just the .com but also who we were on Facebook, who we wanted to be on Instagram, etc. And then of course the platforms just keep multiplying.”

Today, Condé Nast Traveler essentially operates one brand with interlocked content across many platforms; a writer researching a hotel for a print feature, for instance, will take photos and notes for use on the web, along with social channels. Other publishers have found success with this model, as well.

There is only one percent reader duplication between its print and web editions, and the cntraveler.com site receives about seven million unique visitors each month, almost ten times its print circulation.

Content Matters

Other travel magazines weren’t immune to the downturn. Vacations are one of the first things sacrificed by families during an economic downturn, and it follows that travel companies will be hesitant to purchase pricey print ads during these periods.

Travel + Leisure dropped from 1,481.11 ad pages in 2008 to 967.48 in 2011, according to The Association of Magazine Media. By 2013, both magazines would reorient their coverage towards luxury consumers in an effort to become a luxury lifestyle publication and attract higher spending advertisers. For these consumers, travel is a lifestyle instead of a yearly escape.

Source: MPA

“I think what we've seen is that travel has just become more central to people's lives,” said Travel + Leisure's Lump. “I think that's partially what has allowed us to grow, but I also think it's allowed us to have more varying touch points with the consumer and lifestyle. I think it's not so much that we've moved just moved away from core travel it's that all the elements that people play, that have never touched travel before, have become closer to travel than they used to be.”

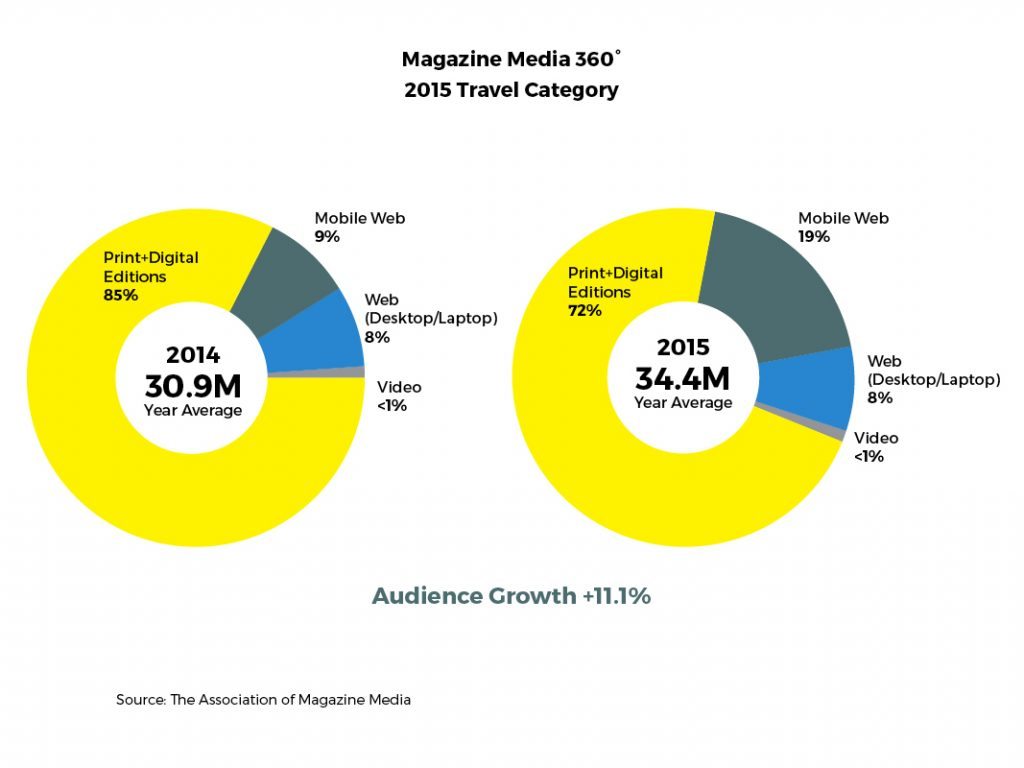

Part of this shift has involved more general interest clickbait stories on the Web, in a stark contrast to the long features and deeply researched packages print travel media is known for. The readership of magazines at large has shifted to older and more affluent readers. Research from the American Magazine Association shows that devoted magazine readers are more likely to go on vacations than those who prefer other types of media.

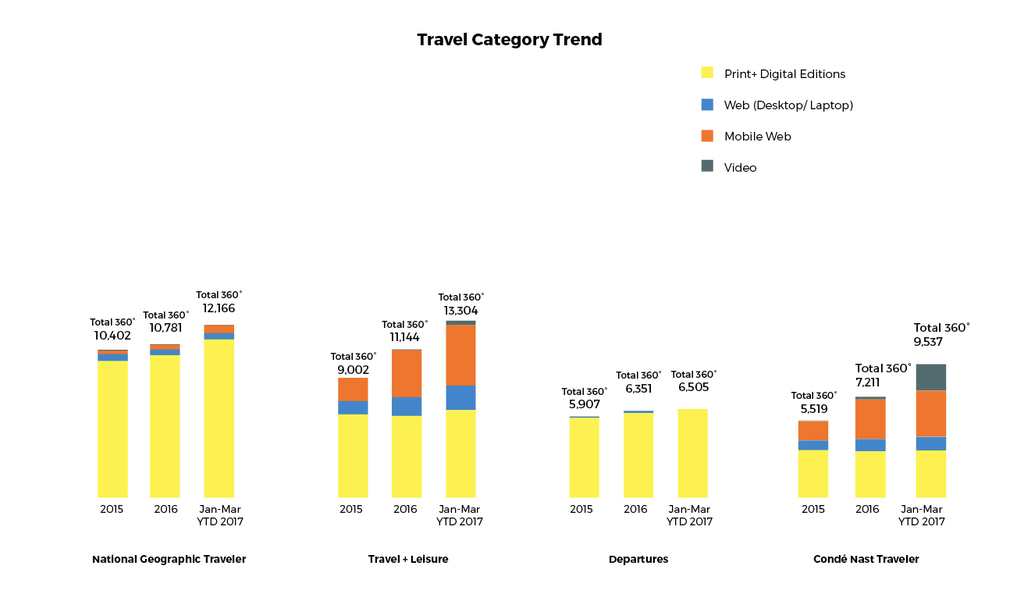

The use of mobile devices to view travel content is also on the rise, perhaps at the expense of print and digital magazine content.

There is the pain point of figuring out an internal work flow that functions across platforms. Journalists, writers, and content creators often have specialized skillsets, so asking one to write a story, create a listicle, take photos, and film compelling videos about a trip is a major challenge.

“We just started working more efficiently that way and it really, it's painful to integrate digital and print,” said Guzmán. “The plays are different, the workloads are different, the story ideation is different. In doing this, there's this huge cultural shift that is exciting and difficult.”

NOT JUST MAGAZINES

Newspapers, as well, began to shutter their travel sections in order to save money.

In 2012, USA Today eliminated its print travel section, moving travel coverage to its Life section instead, mimicking the pivot of travel magazines to more of a lifestyle positioning. Dozens of other newspapers, ranging from The Los Angeles Times to The Washington Post stopped publishing print travel sections as well.

USA Today also tried to pivot by acquiring content and online travel booking companies, like the struggling Tripology in 2013 which it used to sell qualified leads to travel agents.

Newspapers adopted the wrong strategy at the time; instead of doubling down on quality content that would remain useful to readers in years to come, they either decreased quality in a move toward online clickbait or shut down their travel sections completely.

“Newspapers took the single most misguided step I can imagine; if you picture an entire newspaper’s content, there is no content that is more reusable in the future than the travel section,” said Spud Hilton, longtime editor of the San Francisco Chronicle’s travel section. “Let’s say I've had a newspaper that’s had a travel section for 30 years, and then I decide I'm going to throw all that away because it’s too expensive to run a travel section. If I just take the last five years of those and get somebody to update them or hire an intern, I have 250 weekend escapes that are professionally written and have professional photography. That can become an app, website, book, or any number of things that can be used again. Those newspapers were out and out stupid to bury that archive never to be seen again.”

The San Francisco Chronicle was perhaps uniquely well-suited to adapt to changes in digital media; it operates one traditional newspaper site and SFGate.com, which is a scale play that often attracts readers with lighter news.

“I could have written the greatest travel story ever known, and it would not have gotten on the cover of the traffic oriented site because a Swedish bikini team saved a kitten from a tree; which is going to be more popular?” said Hilton. “The Chronicle is a good example of what has happened and what sort of needs to happen which is separating out what is popular from what is good. The difference between what’s popular and what’s good, based on news judgement, should make the difference in the long run. Travel, honestly, has always been some of the weakest journalism there is, and unfortunately that’s because we assume people only want to be fed the cotton candy. It’s our job to give them something good, but also figure out how to draw them in in a way they want to read.”

Guidebooks, as well, were hit extremely hard by the economic downturn, with print sales falling by 50 percent overall. This slump touched off a wave of consolidation in the industry. Google acquired Zagat for $151 million, and proceeded to integrate Zagat restaurant information into its Maps listings after rebranding the company as Zagat Travel. Google also bought Frommers for $23 million, eventually selling the company back to Arthur Frommer without its social media accounts.

Lonely Planet was acquired by BBC Worldwide for $210 million total in 2011 in a series of transactions beginning in 2007. In 2013, BBC sold off Lonely Planet to a U.S. billionaire for just $75 million.

Today, Lonely Planet has emerged from the fray as the most successful guidebook brand in the world, while also expanding into the digital space with apps and video content. By investing heavily in its digital presence while growing its library of guidebooks and other print titles, Lonely Planet has been able to grow while other guidebook companies haven’t.

“We’ve aggressively rebuilt our mobile web and main web platform, that's obviously been ongoing for a few years,” said Lonely Planet CEO Daniel Houghton. “We’re also excited about what’s happened with the guide mobile app, we’ve aggressively expanded the cities from 30 to north of 100 and we’ll continue to grow. We’ve got a big year planned. We’re still expanding our content coverage with more books and types of content, more coffee table trade and reference titles, titles far beyond just guidebook content.”

Lonely Planet’s quarterly U.S. magazine is based off of Arthur Frommer's Budget Travel Magazine, whose assets were acquired by the company in 2014 for $2.4 million, and the company operates 11 other magazines around the world. This multi-platform approach seems to have benefits in consumer travel media, especially since it appeals to travelers across many different levels of the travel marketing funnel.

“We have a core audience that is a fan of our blue spine guidebooks, and we release different collections like our best of series,” said Houghton. “It’s more about having a different product based on the kind of travel you want to do. Lonely Planet means a lot of things to a lot of different people; some people may have never bought one our books but watched the tv show, some people may have just subscribe to the magazine and don’t have an awareness of the other platforms. The most important piece has been authenticity. It’s great content that helps you discover incredible places, we’re very proud of that but also excited to create content to inspire people when they’re not on the road. We all don’t get to travel all the time.”

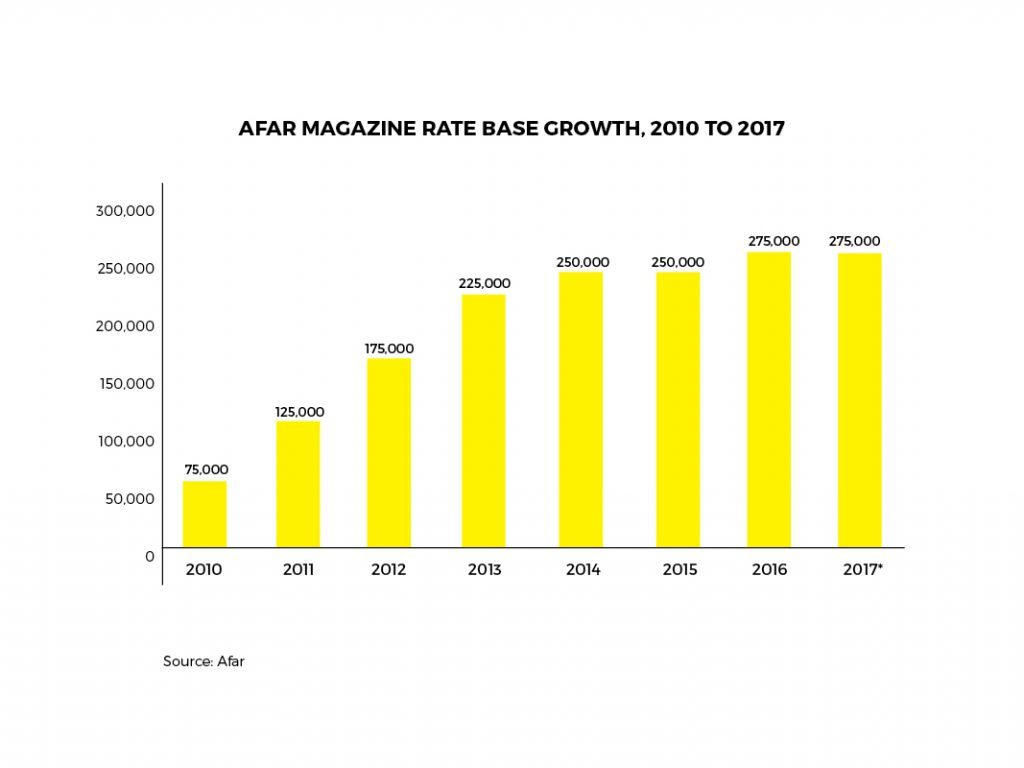

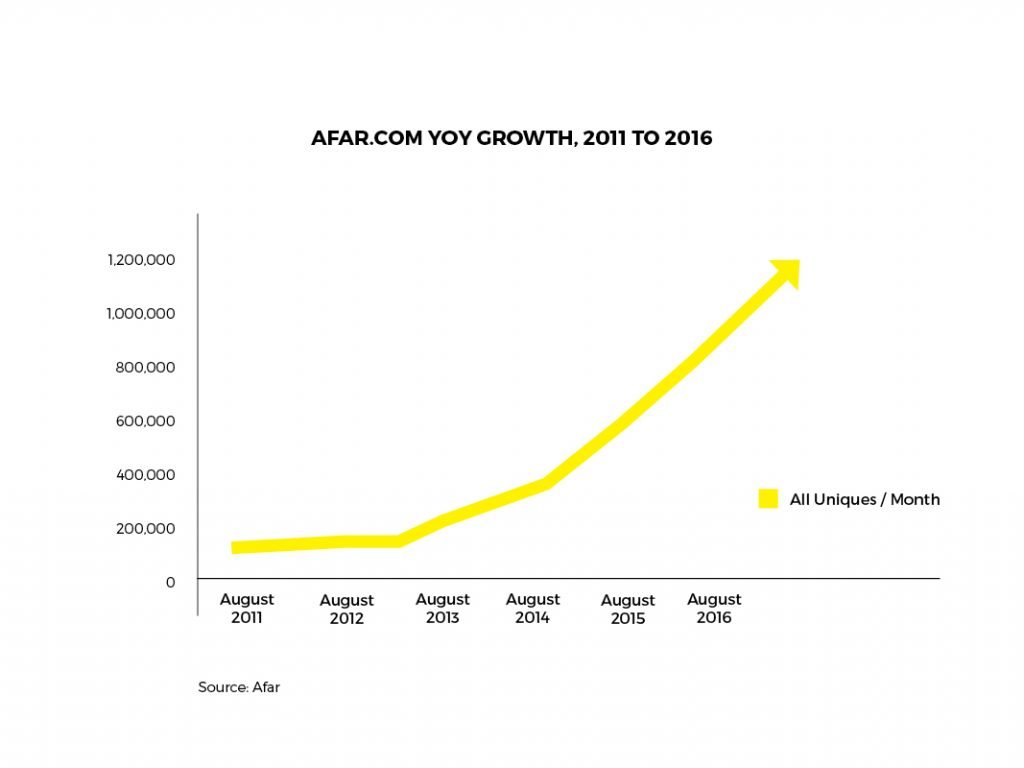

Newer travel magazines seemed to fare better during the downturn. Afar, which launched in 2009, has grown its circulation and digital usership over the same period that legacy magazines struggled.

“We started with the print magazine in 2009, we really felt like it was a really strong kind of way to plant a flag in the sand and determine what our point of view and perspective on travel is going to be,” said Julia Cosgrove, editor in chief of Afar Media. “We were pretty early to the experiential travel movement and we held true to that mission and to that focus ever since then. I really see print as the place where you give people this great travel inspiration where you tell them ... you give them great storytelling, you give them provocative photography, you give them whole design, and it's this nice lean-back experience in magazine form. When digital comes in, it's really all about service and providing resources to travelers to help them travel better.”

Afar grown its traction among U.S. consumer travel magazines. Yet due to the move away from print advertising by travel brands, a more robust digital presence gives magazines like Afar the ability to appeal to advertisers with cheaper and more diverse advertising packages.

Dozens of other niche travel magazines with sleek design and longform reporting, like Cereal, Suitcase, Boat, and others, have filled the gap as bigger travel media brands have largely worked to grow their digital scale. Yet these publications don’t really have an established business model behind them, despite their slick production and contemporary aesthetics.

Most print publications also have branded trips available for purchase online, with ads appearing in their print editions as well, representing another revenue stream in an industry searching for the way forward.

At its core, the struggle of travel media companies to adapt to the digital is tied to the habits and desires of consumers themselves. Not many readers will take the time to sit and read a lengthy story on a destination anymore, opting instead for a quirky but flimsy story that entertains them or a bevy of user generated reviews.

Advertising Shift

As the travel inspiration funnel shifted for consumers away from its historical norms, advertisers began to look for new ways to influence their behavior. Consumers, basically, no longer pay attention to advertising like they used to. Inundated by digital ads, what worked for advertising just a decade ago is no longer effective.

Traditionally, a traveler was inspired by a combination of print advertising in travel magazines or newspaper sections, weekly travel coverage in their newspaper of choice, and TV advertising. Before online booking went mainstream, they would also likely visit a travel agent or contact a vacation company directly and receive brochures featuring photos and the salient information about a trip, vacation, or destination.

Today, online reviews are perhaps the most important source of inspiration for travelers. In that way, the role of the travel media as the trusted gatekeeper for travelers has been completely abdicated.

“In general, people don't read a review and make a decision,” said Barbara Messing, chief marketing officer of TripAdvisor. “Consumers will read six to eight reviews. They might dig in a certain characteristic that they are interested in, maybe they really are interested in what the quality of the beach is, or maybe they are really interested in whether it's kid friendly or not kid friendly. In general, people will hone in on the characteristics of something that's most important to them, find that answer on TripAdvisor, get that most recent insights, check out the photos, check the forums, and really be able to make an informed decision of whether something is right for them. I think that the notion that people could rely on the wisdom of the crowd and the wisdom of individuals to their detriment, I just think that's false, and I don't think the reality is that is going to happen.”

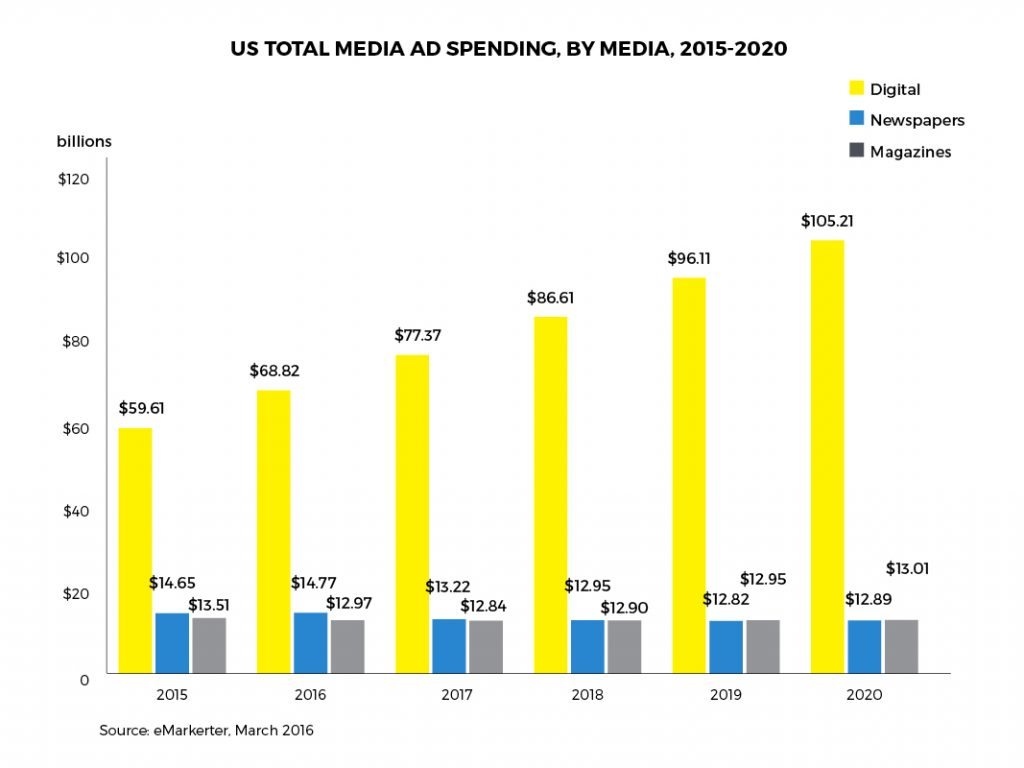

While print advertising still has a place for many brands, particularly in the luxury travel space, there has been a great deal of experimentation with new formats by travel brands as travelers look for inspiration online. Advertisers are looking for packages involving multimedia and social media, not just a print component.

Research from eMarketer indicates that 46 percent of travel brands advertised on social media in 2016, a 12.1 increase over the previous year. They also expect print advertising overall to fall in coming years.

“The conversations with advertisers, and I've watched it evolve, tend to be about all of the channels,” said Guzmán. “Everybody wants the whole deal… our print business is still strong, obviously we have to keep an eye on it. It gets harder because more people are moving to digital, but I think the argument for the premium environment is strong.”

A recent Skift Research report on The State of Destination Marketing in 2017 found that 57 percent of destination marketing organizations said digital marketing has the best return on marketing spending, compared to just two percent for offline advertising.

Platform disruption has made this a necessity, not a luxury. Companies like Marriott International have invested heavily in creating their own written and video content to reach travelers outside of the travel media. Many brands partner with influencers on Facebook and Instagram to provide coverage of new properties or vacations.

“The point of content marketing is to give the consumer help or entertainment in exchange for nothing at first,” reads the 2013 Skift Research report Content Marketing Trends in the Travel Industry. “It elevates the brand and engages consumers long before they come close to a buying decision. Brands in every industry pack marketing close to the transaction, content helps build a relationship long before the trip planning stage.

“For the travel industry, content can help build travel aspirations, associate the brand with the target customer demographic, and raise awareness of lesser-known aspects of a destination or service. Many travel brands and destinations have tools to help plan trips, but they also need to help ease fears and uncertainty of travel.”

This change has also coincided with consumer travel media becoming digital enterprises, leaving content marketing as one of the preferred methods for reaching travelers. As advertising in travel media shifted away from print ads toward digital platforms and native content, the trends have somewhat undercut print advertising, the biggest cash cow for travel magazines.

“I felt like that landscape has shifted from a kind of slightly more traditional environment... You're a high-end traveler and you book on your own,” said Guzmán. “When you go on more trips, [there’s still the] bucket list safari, that still exists among a certain set, but it's really changed obviously for the 30- or 40-something who is much more inclined to sort of cross-shop, with all different kinds of inspiration.”

Print travel media, following the economic downturn that gutted their advertising business, experimented with various digital formats. For a few years, it seemed like tablet editions of print content could be the savior they sorely needed.

Condé Nast Traveler launched its tablet edition in 2011, while Travel + Leisure beat them to market in late 2010, offering the digital edition of the magazine for $3.99, a 20 percent discount off the newsstand price. But not many consumers were will to pay for a digital version of print content when they could just go online and read similar stories for free.

“The iPad was just going to be this Jesus of magazines and I never really quite believed that because I knew how challenging it was was to rejigger the content to fit that format,” said Frank, who oversaw Travel + Leisure’s digital strategy in the early 2010s. “Having just gone through the process of signing up and downloading a magazine, it took forever and was buggy and it just wasn't necessarily a great solution. I was never really bought the gospel that the tablet was going to be our savior. But we did it. I mean, we created a great app and it was beautiful. It won awards, but that was knowing what the usership was is a little disheartening.”

This fragmentation also poses a serious challenge for travel brands looking to get their message out. With more formats available than ever before, public relations professionals began to have to choose between formats based on what they think will resonate most strongly with travelers looking for inspiration.

“I think there is a perception that the print version provides something that online doesn't,” said Nancy Friedman, partner at NFFPR, which recently merged with MMGY Global. “So, we still need both, but it really feels like the balance is going more online. It's really our job to do the education of clients, so they understand the influence, the enormity, and opportunity of these shifts. That's really incumbent on the PR practitioner to do and to arm themselves with the right information and the right statistics to sell it to their client.”

Print has an immediacy and more qualified audience, but it is expensive and provides less of an impact on the normal consumer who searches the web for travel inspiration.

“As much as people might say there are a lot of publications closing or consolidating, we find that there's more places we have to be, that we have to evaluate,” said Jennifer Hawkins, founder and president of Hawkins International Public Relations. “We're not interested in all of them but we have to evaluate each of these different platforms.

“A lot of them aren't [affordable for our clients]. A lot of the budget is now going toward paid influencers, which takes away from the print marketing budget. And that's the thing [print publications are] struggling with the most, the amount of outlets that they have to compete with. Digital is nipping at their heels the most, and digital is probably their biggest competition. Maybe an influencer that offers to do live Facebook streams, shoot some video while they're down there, and contribute to their blog. Clients usually tell us to make a decision and there's not an endless pot of gold that we can sprinkle around.”

The desire for tapping influencers to promote a brand or destination is especially attractive in a period when many have turned to Instagram and other social media platforms for travel inspiration.

But a new format poses new problems. Some influencers charge quite a bit for their services, which can eat into a brand’s overall marketing budget. Others are simply willing to try a product and broadcast their experience to followers. How should a travel brand looking to market itself on social media view the efficacy of influencers, especially during a time when influencer marketing has become mainstream?

“Every client is now asking for influencer coverage,” said Friedman. “What we're trying to express to them is that there’s a huge spectrum of influencers out there and some people have followers. Others have loyal and intense followers, who really listen to them and really act upon what they're reading and seeing. How do you reach out to them, and what does it cost to interact with them? What kind of deal can you strike?

“It's no different in a way that traditional media relations where certain outlets you'd invest a lot in, others you don't. There's a big learning curve on both sides there. The best influencers are really the organic ones, in my opinion, versus paid.”

Does influencer marketing really work, though? No one is really sure. A report from Linqia polling 170 marketers in late 2016 found that while 94 percent of brands which use influencer marketing find it effective, 78 percent also said that determining ROI on their influencer marketing is their greatest challenge in 2017. Instagram and Facebook are the most popular channels for marketers, with 87 percent identifying them as their most important influencer marketing platforms.

Those polled for the report spent $25,000 to $50,000 on each campaign influencer marketing program. It’s easy to see, in the travel space, how spend can quickly shift away from print advertising to digital influencers considering the perceived success of influencer marketing programs. One 4C full page of advertising in Travel + Leisure was priced at $157,000 in 2016; with that spend, a brand could instead run three to six influencer campaigns.

Clickbait and Video

So how does the modern travel media brand deal with the changing habits of travelers while maintaining an editorial voice and vision?

Afar, for instance, has a few sections on its website devoted to travel lifestyle, discovery, and more traditional hotel and destination coverage. They’ve also introduced a new bookmarklet to let users save content across the web in one place, a sort of do-it-yourself trip planner.

“We try to focus on less and less about this spray and pray, scale at all costs, race to the bottom type of thing,” said Derek Butcher, chief technology officer of Afar Media. “We kind of came in with a bit of a leg up there with the audience, but building on that by giving this sort of personalized high-engagement experience to the advertiser. That's everything from promising 100 percent share of voice of a certain section by really kind of this technological back-end in terms of how we do tagging to having things like the trip planner. We don't try to get clicks at all costs.”

Pretty much every brand is investing heavily in video, as well. Lonely Planet, for instance, recently debuted a digital video platform on its website in a partnership with GoPro. Travel + Leisure, as well, now has around 500 videos available on its site.

The move towards video content in the wider media is now taking place in travel, and advertisers are interested. But integrated campaigns across multiple platforms are what advertisers are looking for; marketing activations featuring live events have become the new normal for travel brands.

“[Print is important when] you're trying to make a name for yourself or you're really trying to establish a certain kind of reputation,” said Lump. “They're actually paying for the content. You're getting in front of people who are willing to spend more time with the content itself but the intent is to find a more qualified audience.

“I think in terms of digital advertising, a lot of our conversations, they're driven by many things. I still think that digital is the property we need to protect. Also, the digital conversation right now is a lot driven by content. Content marketing. Native advertising. I think that it's an incredible opportunity for advertisers.”

A New Page

Travel media brands are well-positioned to expand and withstand future changes in the digital media ecosystem. But this doesn’t change the fact that there is often a serious disconnect between the breezy, clickbait content on the web and the reality of taking a vacation.

“Travel media, both print and online, tend to paint a rosy picture of travel that often differs from the reality,” said Perrin, who after leaving Conde Nast Traveler went on to found WendyPerrin.com, which provides advice to travelers. “There are many savvy consumers out there who know the difference. They know how easy it is to fall into the trap of a touristy, overcrowded, inefficient, bait-and-switch travel experience. They don’t want to just read about an amazing trip; they want to actually get an amazing trip.

“Many travelers are looking for personalized, sophisticated travel advice from an unbiased source. Travel media can’t easily meet this need because they don’t have people with the necessary expertise or who are unbiased, and publishing advice that’s so specific and narrow that it doesn’t drive enough traffic. In print they can’t meet the need either because they can’t waste their increasingly precious real estate devoting pages to personalized advice.”

Bigger trends in the travel industry also call into question the future of print consumer travel media.

Will aging millennials consume print travel media at all as they earn more and start families, opting to find digital inspiration instead?

Can online travel booking tools, which have helped render the travel agent irrelevant to most, use advanced suggestion and personalization algorithms to one day serve travelers more intimately than any monthly magazine can?

Travel media brands, and the travel companies looking to influence their high-spending readers, should hope not.

Editor's Note: An earlier version of the story included a chart of circulation figures that were incorrect. Because of that the chart has been removed. A second chart containing other methods of measurement and has been verified by an independent publishing group remains.