Skift Take

Skyscanner is becoming an online shop-window for airlines, providing a branded experience that's similar to the airline's own sites. Behind this move is a technological upheaval that's scrambling commercial alliances.

Lots of companies publish whitepapers as thinly disguised marketing. But a new whitepaper from Skyscanner, the travel price comparison company, has actual value. The paper outlines a business view that we haven’t heard a major travel booking company articulate before.

Skyscanner’s paper — A Vision for the Future of Airline Distribution — says that consumers will soon find that visiting metasearch websites will look sort of like a collection of branded airline sites.

The paper focuses on “instant booking,” where travelers buy their plane tickets without leaving the sites or apps of metasearch companies like Skyscanner.

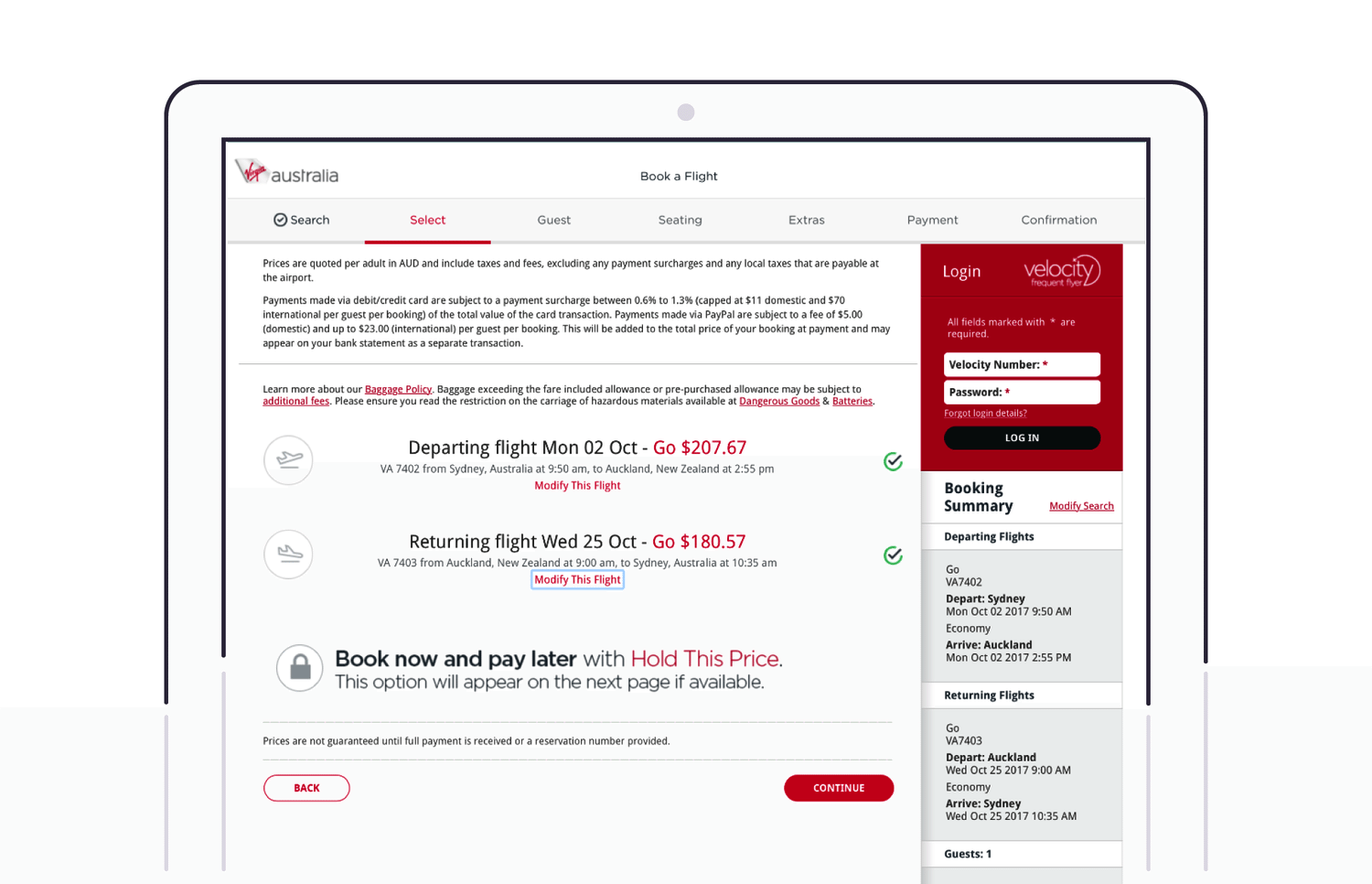

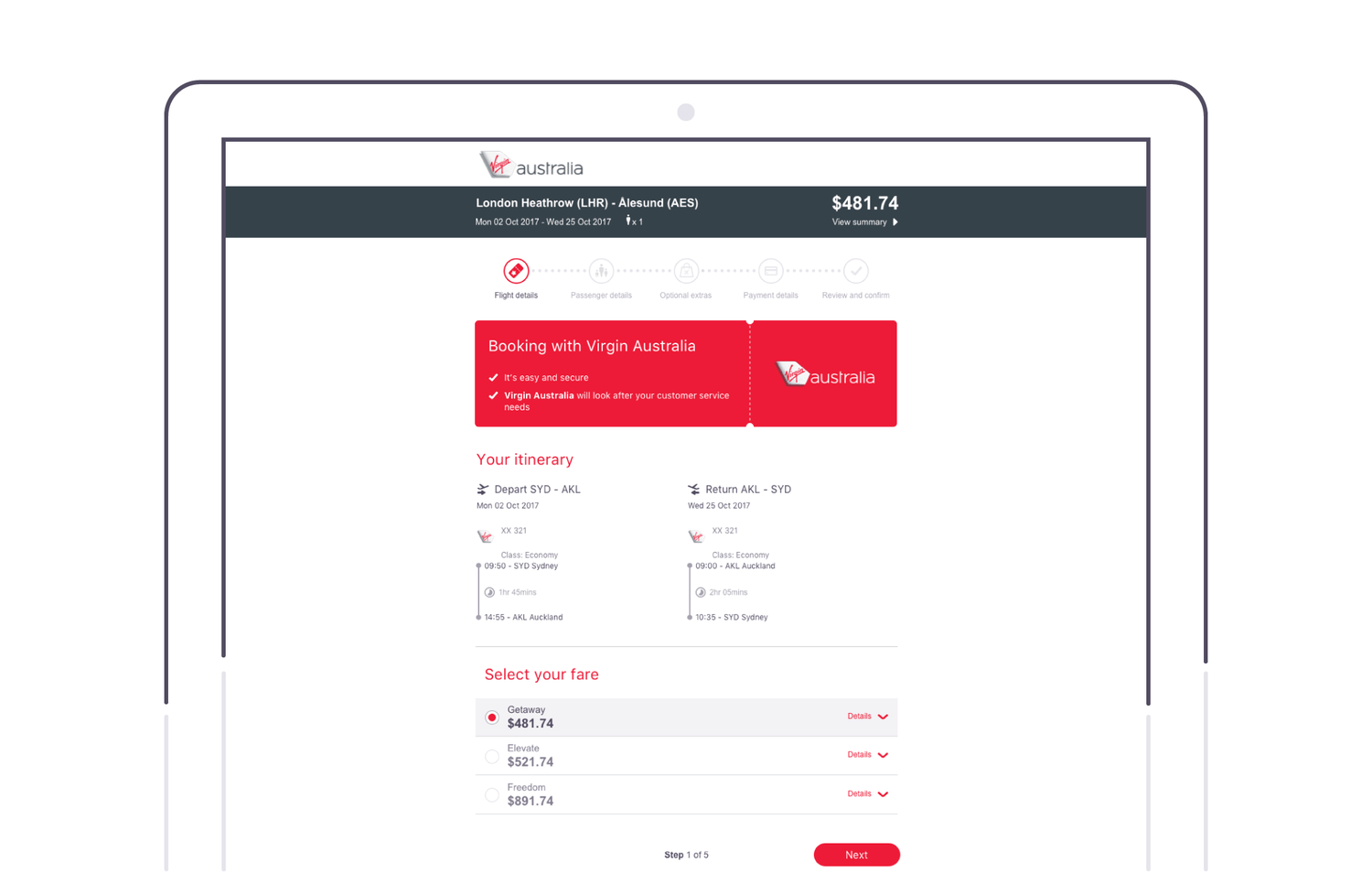

Take a look at these two screenshots. The first is of VirginAustralia.com’s booking page, and the second is of Virgin Australia’s transaction page on Skyscanner. Already today they have a similar look and feel. Over time, the same functionality will be available in both places.

While Skycanner chief executive Gareth Williams did discuss the big picture with Skift in an interview last month, this paper is the first time we’ve heard his company explain in a complete way how instant booking would reshape the commercial landscape.

The technology that powers instant booking is going to unseat legacy companies and give rise to a whole fleet of smaller companies, while also doing wonders for Skyscanner, the paper says.

Like a Chinese-style shopping mall

Ever since last November, when Chinese travel conglomerate Ctrip.com acquired the Edinburgh-based company for $1.74 billion, executives have talked a lot about Chinese website Tmall.com as a metaphor for its future.

Tmall is a Mandarin-language retail marketplace run by retail giant Alibaba. It differs from a retail marketplace like Amazon in that its default format is to have brands run their shops on it.

The Skyscanner strategy is to become more like Tmall. Executives want to give supplier brands space and control to display their products by offering “a storefront of sorts, with abundant upsell purchasing options baked in.”

The report says: “Shopping sites like Tmall… are still marketplaces where sellers must compete for their business but also offer an online shop window for brands that provides the same experience to users as they offer on their own sites.”

“Apply this to metasearch: the winners in this space — both among airlines and intermediaries — will be those that can see the value in bringing a rich and differentiated shopping experience to travelers, across the greatest span of platforms and devices.”

From tactics to strategy

Metasearch companies began as a place where the most price-sensitive travelers shopped for the very cheapest flight. That is not a model for growth. Major airlines can get away with paying companies like Skyscanner as little as 1 percent of a ticket’s value on average as a commission, as Skift Research estimated in its 2017 Outlook on Metasearch in Travel.

To escape the bargain basement economics, the company has long talked about its tactic of promising airlines better upselling opportunities on a vaster scale than they could achieve on their own. Skyscanner has joined its peers Kayak, Momondo, and Wego in outspending the airlines collectively on global customer acquisition and mobile-first marketing.

Skyscanner says its strategy is to become a marketplace where brands stand out and compete on quality rather than price. Along the way, it implies, the airlines will reap higher margin, splitting that money with Skyscanner.

Promising to displace middlemen

New technical and commercial realities are upsetting the old order.

Until recently, four distribution systems Amadeus, Sabre, Travelport, and Travelsky have been the main middlemen. They have provided the computing power to distribute airline tickets worldwide to tens of thousands of travel agencies (online, corporate, and traditional).

Airlines are eager to sideline these middlemen because of their fees, which are seen as excessive, and their services, which are perceived to be outdated.

Skyscanner’s paper says this airline dream is coming to pass: “New initiatives… are pushing the industry to transform the way air tickets are sold to travelers, by allowing for integrations with more product differentiation and access to fuller, more dynamic air content, independent of the traditional global distribution system (GDS).”

Why would Skyscanner bother to involve itself in a long-running battle between airlines and middlemen over distribution?

Because it wants to be a new middleman — and a much cheaper one for airlines.

What about Kayak?

Skyscanner has invested more in direct connections to many airlines, especially low-cost carriers, than its metasearch peers have.

That means Skyscanner often shops for fares by communicating directly with airline computers. The distribution systems handle fewer than 5 percent of the queries (searches or transactions for fares) that customers make on Skyscanner, according to Shane Corstorphine, the general manager of the company’s Americas business and its former chief financial officer, who spoke with Skift Research for our metasearch report.

Kayak, Momondo, Hipmunk, Wego, and other metasearch competitors have not embraced the new technology as rapidly.

Skift’s estimates are that Kayak and the rest sign deals with distribution systems to price a significant chunk of their tickets.

Meanwhile, Google Flights has its own booking engine, and it relies on a company it acquired, ITA Software, as a pricing engine. It doesn’t use distribution systems much.

A coordinated airline effort

An airline lobbying group has championed the adoption of new technical solutions for distributing airfares.

That effort by the International Air Transport Association (IATA) has posed a challenge to the distribution systems like Amadeus and Sabre, which had historically built their systems on a messaging standard called Edifact.

Airlines have lobbied to push everyone to adopt new messaging standards that can handle more sophisticated information.

The concept isn’t magic. IATA’s effort, which Skyscanner is piggybacking on, isn’t a technical breakthrough.

What’s of interest is that the airlines are successfully “mass adopting” the standards, with at least 90 using NDC by 2020.

If all airlines use the same messaging standards, startups and other technology providers will take the risk of investing in new tools.

Why? The entrepreneurs will have confidence that the tools they build for one company could be resold to dozens of others that rely on the same standards.

The airlines’ ultimate dream is that a non-travel company like, say, Facebook, would be able to use the same pipe fixtures, so to speak, to connect to airline plumbing and start selling airfares to its users — without having to hire Amadeus, Sabre, or other companies as plumbers.

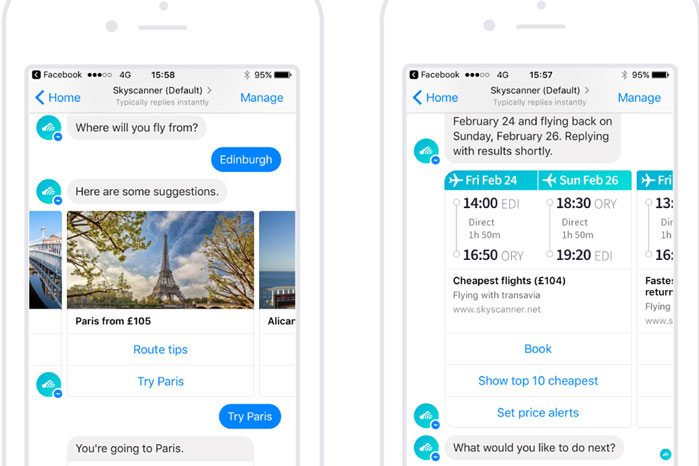

Vendors are already developing chat interfaces for airlines that can distribute content via NDC. As chat becomes effective for booking, platforms like Facebook may have more interest in becoming travel booking gatekeepers.

Leveling up in the distribution game

Skyscanner has been a fan of IATA’s effort. It has done the work so that it can now offer instant booking of flights with any provider that uses IATA’s so-called New Distribution Capability (NDC) standards. It is the only global metasearch to receive certification of Level 3 on IATA’s new standards.

What does that mean? An example may help:

Since November 2015, British Airways has been the first airline to enable the instant booking of tickets without leaving Skyscanner’s site. The process used a basic form of IATA’s standard.

A year later, in November 2016, Skyscanner got the new certification. That allows it to do more advanced tricks. It will be technically able to merchandise British Airways’ baggage, seat choices, and ancillary services. It will be technically able to push the carrier’s images of seats and aircraft to customers.

For its part, British Airways has been doing the work to handle these orders, from booking through fulfillment, using the NDC standards. It may soon enjoy the same flexibility with tickets booked on Skyscanner as if the tickets were booked on its own site, such as letting a customer change their mind about an upsell mid-transaction or at a later time.

Undermining legacy vendors

Until now, if an airline wanted to distribute outside of its site, the shopping and booking would happen via the distribution system on somebody else’s site – such as an online travel agency like Expedia or Lastminute. However, with the NDC API (application programming interface, or a method used for retrieving data), the airline can send the information directly to Skyscanner or another capable company.

In this use of NDC technology, booking happens via the reservation system of the airline, rather than a distribution system, says Filip Filipov, director, product at Skyscanner.

Digging deeper, the airline needs to power its booking page on its own site and mobile app with an API. Otherwise, no bookings can happen. In the past, the distribution system was the only way online travel agencies could access any booking functionality. With the NDC standard, an airline can give the booking API to online agencies and others without the distribution system.

The payoffs: The airline can control its storefront on a metasearch like Skyscanner while avoiding distribution system fees and processes.

Smaller players see sales opportunities

Skift can’t help but notice that, if Skyscanner’s vision of the future is true, the vendors that provide host systems for airlines should have steady streams of revenue. These include HP, EDS, Radixx, and Mercator.

Also benefiting are companies that have specialized in using NDC to power airline IT systems, such as NDC-certified third-party tech providers like JR Technologies or Farelogix

There are other opportunities: Most airlines have the functionality built in-house or via vendors which aren’t distribution systems, such as Datalex and Travelaer. These vendors build solutions called Internet booking engines (IBEs), which handle the interface of making a payment, reserving the seat, retailing, merchandising, and so forth.

Pricing is driving the change. Under the old model, a distribution system might charge an online travel agency X million of dollars to make X billion search requests on the airline’s data via its pipes. Under the new model, the agency connects to the airline’s API – typically free, within limits for the agency, while the provider pays the shopping company (as American Airlines might hypothetically pay ITA Software by Google to power its search of its inventory. (Pricing engines like ITA Software also stand to benefit from current trends.)

The legacy middlemen aren’t rolling over

Not everyone will share Skyscanner’s vision. Some critics might say there are a couple of question marks about its ideas.

The legacy technology providers may adapt, for one thing.

When Finnair began offering instant booking through Skyscanner, it tapped technology firm Navitaire’s technical solutions for the job. Navitaire is owned by Amadeus and uses an API that Amadeus built on the IATA-developed NDC standards and that it released last year.

So a legacy middleman, Amadeus, is co-opting the trend and re-inserting itself.

Skyscanner would likely point out that Amadeus is doing this via a separate line of business called Airline IT, which sells the Amadeus Altea reservation system. The old distribution system fees, are not involved.

Still, Sabre is working on a similar effort with its SabreSonic reservation system. Another of the distribution systems, Travelsky, received Level 3 status last year, too, and it offers a host system for airlines. Another distribution system, Travelport, is close behind Skyscanner in its work and is certified as a Level 1 aggregator and Level 2 IT provider for NDC.

There are other signs that the traditional distribution systems are not going away.

A case in point: The more complicated the itinerary, the better distribution systems are at processing than any other option, especially for so-called interline tickets (such as ones involving one-stop or multiple city legs). Travel management companies will generally prefer to have distribution systems process their searches because they have a speed and accuracy next-generation technologies still struggle with. (That said, Lufthansa’s direct connects to travel management agencies, powered by Farelogix and Travelfusion, are eye-opening.)

Many airlines also continue rely on the distribution systems to confirm pricing if the distribution system provides much of their technology. In that way, when Skyscanner checks with the airline to see what prices it has via a direct connection, the airline’s API may return fares pulled via a distribution system instead of a pricing system like ITA Software by Google.

Distribution systems can also play a role if they power an airline’s Web services, in other words, the software running their websites. An example is Amadeus’ Web Services and Open Jaw Technologies (owned by Travelsky).

To be fair, Skyscanner’s report never writes that the legacy technology middlemen will disappear overnight. Its take on overall industry situation is, instead, to use the metaphor of a spectrum:

“What the current landscape looks like is arguably a spectrum, with direct

distribution at one end, through to third party distribution at the other. At the

third-party end remains the online travel agencies and travel management companies, who are still heavily reliant on GDS, while at the direct end lies airline.com. …

“Which points in the spectrum airlines choose to direct their distribution strategy towards will determine how things unfold; the way they approach new opportunities will be key, and will shape the future of airline distribution.”

Threats to Skyscanner

Assume Skyscanner is right and, to oversimplify, the Internet is making legacy technology middlemen less relevant in many situations. Some critics may point out that the company faces risks.

Say that NDC-style connections lower the bar for entry by non-travel companies. It’s also possible that online travel agencies like Expedia and Priceline could add instant booking and branded experiences, too.

Wait. Doesn’t an online travel agency have a different model from metasearch in that it is the merchant of record on the transaction instead of passing it off to the airline? Yup. But what is to stop, say, Expedia from offering branded airline storefronts, instant-booking style, next to their traditional choices.

As of today, agencies like Expedia and Priceline typically use the distribution systems to process bookings. But more and more they use either the airline’s all-purpose booking APIs or specifically created APIs for clearing the transaction. For example, American Airlines has a solution where an agency can complete a booking via its NDC API, which doesn’t put the booking into the distribution and hence is considered direct into the airline’s host reservation system.

Online travel agency customers who don’t care about brand could buy fares the “old fashioned way” while customers who do care about brand could book via instant booking direct connections, and save the agency some fees charged by the distribution system in the process.

On a different front, Skyscanner might face competition from other platforms, such as Facebook, Amazon, and Alibaba, that are better at aggregating demand and convincing travelers to book on mobile devices. Already, Google has been adding instant booking, and smaller startups, like Flyiin, have signed airlines like Lufthansa to sell tickets in new ways.

Skyscanner believes that what makes it distinct from an online travel agency or a distribution system is that it offers “an end-to-end user experience on one platform across the span of devices” and that it gives traveler “the full choice of providers, with rich ticket options and the ability to for airlines to showcase their brand to an extent which is beyond that which most other platforms are currently offering.”

But the major online travel agencies and new gatekeepers like Facebook ought to be able to duplicate those advantages if they choose.

Some critics say all of the metasearch companies overstate their success at presenting different airline bundled products and upsets search results in a fair, apples-to-apples way.

Airlines have been “unbundling” their products, such as by charging for seat assignments or overhead bin usage. Unbundling enables them to get passengers to pay more for services without starting price wars with rivals. For instance, should a ticket that’s cheap but that also lacks access to the overhead bin and a free meal be displayed underneath a ticket that has those perks? All metasearch companies are still struggling with that display challenge.

In short, Skyscanner’s vision for the future of airline distribution is provocative, detailed, and clearly argued. But the industry will likely debate its conclusions at Skift Forum Europe, where Skyscanner’s CEO will be on stage,” and in other venues for years to come.

The Daily Newsletter

Our daily coverage of the global travel industry. Written by editors and analysts from across Skift’s brands.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: airline marketing, airlines, ctrip, distribution, gds, metasearch, skyscanner

Photo credit: Workers at Skyscanner's Edinburgh headquarters are optimistic about the future of travel distribution. The Scottish-based, Chinese owned company sees itself becoming the center (or "centre", or "中心") of distribution. Skyscanner