Airlines Become More Sophisticated With Personalized Offers for Passengers

Skift Take

Just before Christmas, Iberia Airlines sent emails to some customers. If they could vacation anywhere, the airline asked, where would they like to go? And with whom?

Iberia asked customers to go to a special website, where they would share information on their travel desires and contact information for a favored travel partner. A little later, the customer's friend would receive an email from Iberia. "Feliz Navidad," it started, before explaining that the friend had created a special travel-related holiday card, with help from Iberia.

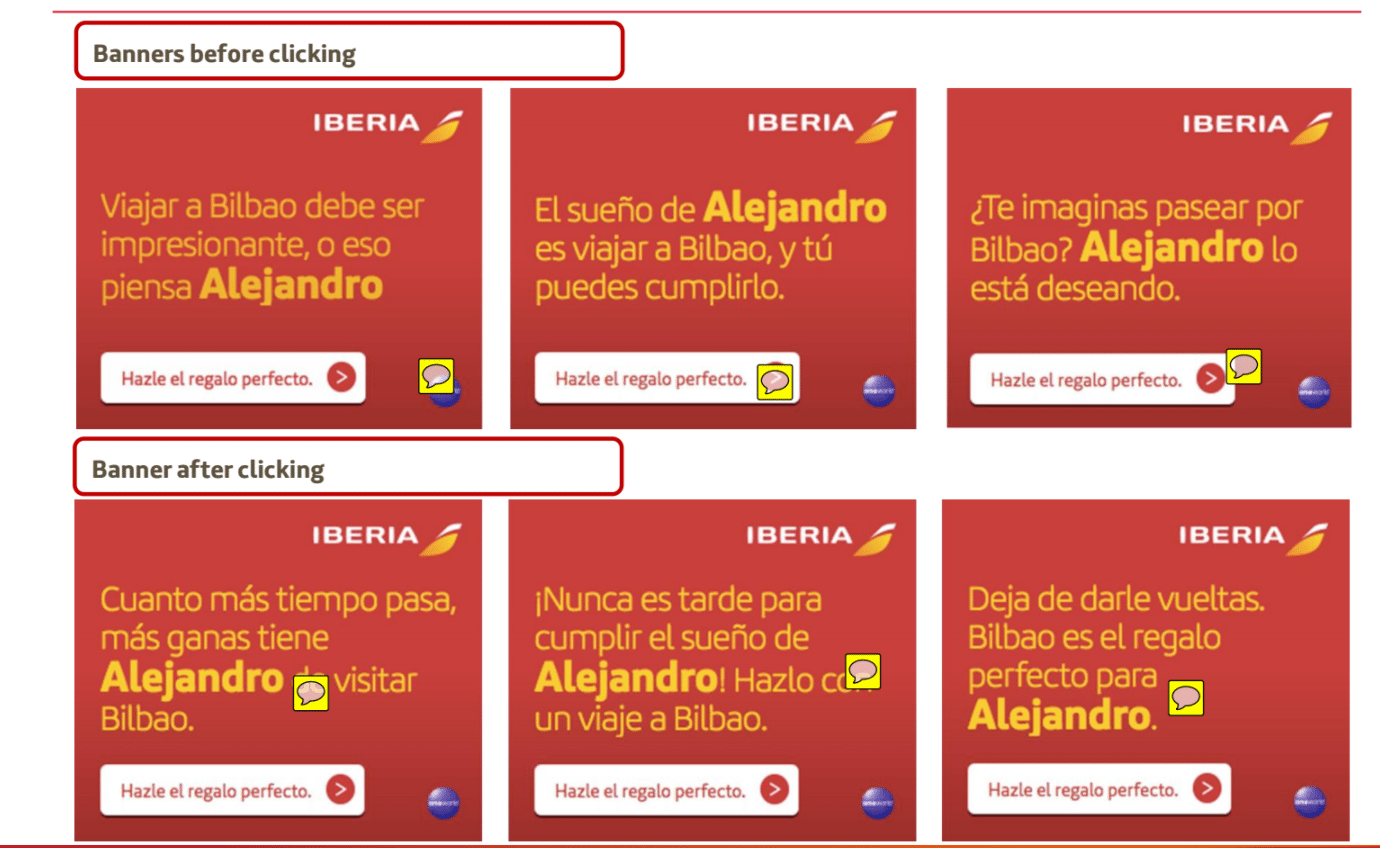

To view it, all the recipient had to do was click on a link. Iberia then put its advertising budget to work, using cookies so the traveler's friend would see banners across the web, suggesting the perfect Christmas gift. "Alejandro's dream is to travel to Bilbao," one might read, "and you can fulfill it." Another might suggest, "It's never too late to fulfill Alejandro's dream. Do it with a trip to Bilbao."

It was a small promotion, running for fewer than three weeks and only in Spain. And it wasn't easy for Iberia to measure its effectiveness, since the airline could only a see a correlation on revenues if a person clicked on the ad and bought tickets. But Iberia's Christmas promotion shows how some airlines are working to target offers not to general market segments, but to individuals. They want to provide the right offer to the right person at the most opportune time — all to generate more revenue.

"It's about relevance," Iberia Chief Commercial Officer Marco Sansavini said in an interview. "I will offer to you what is relevant to you, which is not necessarily what is relevant to your friend that is next to you."

Airlines were among the first retailers to divide consumer groups and price accordingly, charging different fares for the same product based on a market segment's perceived ability to pay. That's why business travelers tend to pay higher fares than leisure customers, even when both fly the same routes.

But with retailers like Amazon and content companies such as Netflix using more sophisticated technology to monitor consumer needs and react accordingly, airlines sometimes struggle to keep up. If Amazon can vary pricing on a whim, according to individual tastes, why can't airlines? And If Netflix can guess, with reasonable accuracy, what movie a person might enjoy, shouldn't airlines know where a traveler might fly next? Or shouldn't an airline know what ancillary option a loyal traveler might want? Perhaps lounge access? Or an upgrade to premium economy?

Many companies, including Lufthansa Group, are working to analyze customer data so they can guess what customers will want — perhaps even before they know.

"You don't want to be spooky," said Marcus Casey, Lufthansa's vice president for personalized customer experience, analytics and data management. "We all don't know what Facebook knows about us, right? But if you're open with how you handle data, the opportunities are immense."

Working to Learn Customer Needs

At its Munich hub, Lufthansa is testing approaches to better understand customer needs.

In one program, the airline has deployed sensors and bluetooth beacons so it can message customers in real-time. Often, when a targeted passenger comes through security — and has bluetooth enabled on his phone — the airline's personalization program starts working.

First, what the airline calls its "Big Data Engine" examines the customer's mobile boarding pass and calculates how much time the traveler has before departure. If it's more than 65 minutes, the system examines the customer's profile in Lufthansa's frequent flyer program, called Miles and More, to see if the passenger has free airport lounge access. If not, the system considers making the customer a lounge offer — but only after evaluating whether the customer might buy it.

"We look at his Miles and More profile and ask, does he have an affinity for this product?" said David Doyle, Lufthansa's director for personalized customer experience. "Based on that affinity score, we also then contact the lounge system. We have sensors in the lounge that tell us how much space there is. [If there's space,] the beacon then sends a signal to the app and the customer gets then an offer for the business lounge for 25 euros."

The lounge promotion is part of what Lufthansa calls SMILE, a companywide program dedicated to personalizing travel. Many Lufthansa Group customers — the company owns Swiss Air Lines, Brussels Airlines, Austrian Airlines, and the low-cost airline Eurowings — may have some interaction with the program, though they may not know it.

For many, SMILE kicks in after booking, as the airline decides which ancillary items it might offer. Options include hotels, rental cars, trip insurance, lounge access, or upgrades to business class or premium economy.

In the past, Lufthansa discovered bombarding customers with all of their options wasn't effective. Now, it sends offers to customers only when its data engine suspects passengers might want them. The system may take into account whether it thinks the person is traveling on business or leisure, or where the customer bought the ticket — through Lufthansa or a through a travel agent.

For example, if Lufthansa thinks a customer is traveling on business, it might not offer travel insurance, as it will guess the passenger's company has a policy for its employees.

"You can send something out and it has all the offers," Casey said. "But your eye will catch two and not 10 offers. The important thing is, 'how relevant is what I send you?' When is the best time to offer you what product through what device? When are you most susceptible of wanting to buy something? That might not be two weeks before you fly, if it's an upgrade. Maybe it's when you get to the airport, or you're packing your bags and you say, 'Damn, I have 12 hours in economy class ahead of me.' Then if you get the offer, you will buy. It's behavioral economics, basically."

Sometimes, Lufthansa makes decisions about customer needs that don't involve generating sales. If it looks at a traveler's itinerary and notices the person is flying from London to Frankfurt for the day, it may not send detailed destination information, said Alexander Prinz, a member of Lufthansa's big data analytics team.

"Maybe we don't want to send you weather information for Frankfurt because we know you fly in during the morning and fly out during the evening," he said. "You're most probably a business traveler. What will you see of Frankfurt? You will see arrivals, the taxi driver, your office, maybe a meeting room, the taxi driver, the terminal and that's about it."

Prinz said Lufthansa is working on bigger — and perhaps more fun — projects. Lufthansa is trying a Netflix-style algorithm that seeks to guess where its most frequent flyers would like to vacation next.

"We can find people who are flying are statistical twins," he said.[We'll say to a customer,] 'This guy, He flew to there. You didn't.' Why don't we offer this to you? You two fit perfectly together."

Far from perfect

While Lufthansa and Iberia brag about their personalization strategies, the general consensus is that airlines have work to do before they will always sell the right product to the right person at the best time.

For many carriers, technology is a major issue. Airlines were among the first companies to embrace computers, and among the first to sell on the web. That put them ahead in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, but today, a lot of airlines rely on antiquated technology for some systems.

Many airlines have invested in modernizing some channels, while keeping other systems as they were a decade or two ago. Sometimes that creates a problem where the personalization is not consistent across the entire experience, said Dermot O'Connor, co-founder and vice president for product and engineering at Boxever, a firm that helps airlines craft personalization strategies.

It's a problem, he said, when an airline tailors messages to customers via email or push notifications, but its employees know little about that same customer if the passenger approaches an airport service desk or calls the reservations line. Amazon rarely faces this issue, he said, in part because its employees generally do not interact face-to-face with customers.

O'Connor added that some airlines "silo" their data, so one part of an airline does not share customer information with another.

"They have a real challenge in knowing their customers and talking to their customers across all their business channels," O'Connor said. "Who is doing that well? No one. That's a really difficult problem. That's what everyone is trying to solve."

Campbell Wilson, senior vice president for sales and marketing at Singapore Airlines, said developing personalization strategies across channels is a problem because airlines are unusually complex businesses. He acknowledged airlines may have more information about customers than most corporations, including from their frequent flyer programs, but said knowing what to do with that data is more difficult than it may appear.

"It's very true that we can analyze our data such that we can determine what characteristics lead to a propensity to do a certain thing like buying preferred seats, upgrade, preference for a certain type of meal," Wilson said. "Airlines have the pleasure and the pain of having massive amounts of data, but to get insight from that data, then translate it through to a delivery mechanism in an airline context is also not as easy as in other industries. "

Even Iberia's Sansavini said it could be awhile before airlines match Amazon or other sophisticated retailers. Those companies often are solely focused on e-commerce, he noted, while airlines are essentially transportation businesses.

"We are not designed as an airline to provide truly individual experiences," he said. "We are sort of a factory that serves millions of passengers."

Using data to vary prices

If airlines ever hone their personalization programs, many insiders see a logistical next step — carriers may vary prices according to how much their systems think a passenger will pay.

Take Alejandro, the Iberia customer hoping to visit Bilbao. An airline should know whether Alejandro is a 22-year-old college student who usually buys the cheapest tickets, or a 50-year old father who often flies in business class. The airline could offer different prices depending on what it knows about Alejandro.

But most airlines are not there yet.

"The issue is that our revenue management systems are not sophisticated enough to take into account the individual profile," Iberia's Sansavini said. "They work based on segments. The issue is, how much will technology be able to evolve? Ideally, you'd like to get to a segment of one person. That's ultimately what our aspiration is."

British Airways CEO Alex Cruz has a similar view. He told Skift in November that the current way industry pricing strategy is "not survivable." (His airline is owned by International Airlines Group, the same company that controls Iberia.)

"We’ve been talking about being able to walk up to McDonald’s and a Coke costs [a] different [price] at any time of the day," Cruz said. "Ultimately, a Coke is going to cost different if it’s you or I that goes up to the counter. I think pricing is going to go in that direction. In the beginning, [the company] will be able to know who we are, where we are, [and] what sort of need we have. How much are we really willing to pay for the ticket?"

Still, not everyone is sure airlines will take it so far. Boxever's O'Connor said he suspects airlines will sharpen pricing schemes, but he said airlines probably won't sell the same package at the same time for two different prices, because that approach would irritate customers.

But an airline could use what it knows about customers to promote either a higher priced or lower priced package, he said. If Iberia knew a customer preferred business class, the airline might try to hide its cheaper fares, or put them at the bottom of a list.

"Changing the price for a particular person has been discussed but hasn't been done," O'Connor said. "There has been talk about showing only certain options based on our likes. It might be a higher price for your because based on data analytics the airline knows you usually prefer a certain time or a certain class. That's probably the fairest way to do it. You're not manipulating the customer. You are just putting the most applicable fare in front of them, and they can choose a cheaper fare if they want it."

Iberia's Sansavini said he knows airlines cannot use data about customers to charge them higher prices every time.

"Personalization is about two things," Sansavini said. "One is about having the right offer at the right moment. But the other is having the relationship where the customer trusts to give you all the information because they believe that will help us treat you better."

Lufthansa's Casey said airlines must be transparent. That's important to Lufthansa, because German privacy laws require customers opt-in before airlines can access to most data. But if customers feel they're being cheated, they might not give permission.

Casey said Lufthansa could change how it charges for lounge access. Today, when a customer enters the terminal in Munich, Lufthansa's data engine makes a simple decision, asking whether the customer might want lounge access and whether the lounge has room. In that case, the price is always the same — 25 Euros. But what if it's snowing, and the customer's flight is delayed by four hours? In that situation, many flights are likely delayed, so the lounge is probably busy.

Now, Lufthansa might tell the customer the lounge is full. But what if Lufthansa thought in terms of surge pricing? Perhaps, this time, the price would be 50 Euros.

"If you're open with the reasoning behind it then you can do these things," Casey said. "I think you need to be as transparent as possible to the customer. You can do it just as Uber does it. They say, now we have heavy demand. It's raining in New York. There are no cabs. Are you willing to pay double? Maybe with the lounge, you can say, 'There's heavy demand to go into the lounge right now.'"

Casey said he fears travelers may object to paying different prices according to factors outside their control. But he noted airlines have been practicing price discrimination, in some form, for decades.

"If you're trying to be opaque that might hurt you," Casey said. "But then again, the aviation industry has proven be able to sell three different products on the plane at 10,000 price levels."