Skift Take

Airbnb's combative tone speaks to the severity of the issue for the sharing brand.

Up until late in the afternoon on Good Friday, Airbnb and New York State were in discussions to settle the state Attorney General’s subpoena for a set of the short-term rental site’s user data.

According to sources Skift spoke to, talks fell apart because Airbnb would not agree to limits on how many listings a person could have in New York City. [Ed. Note: Updated with statement from Airbnb, below]

Airbnb has made conciliatory overtures to municipalities in the form of proposals for its users to pay hotel taxes, but behind the scenes it is suiting up for battle in San Francisco and New York City, its two most important markets.

For the short-term rental service, the battle hinges on how many listings hosts can have, and how often they can rent them out.

This afternoon, Airbnb reiterated that it would remove “more than 2,000 listings” in New York managed by hosts that “weren’t delivering the kind of hospitality our guests expect and deserve.”

The move comes less that 24 hours before Airbnb faces New York’s Attorney General in court. On Tuesday Airbnb will meet representatives from the Attorney General’s office in a courtroom in Albany to argue over a subpoena related to hosts in New York [embedded below] that have more than one listing on the site, or who rent out their place when they’re not present.

In San Francisco, Airbnb’s leaders are meeting with city council members in order to negotiate away key provisions in a new law that would make Airbnb legal in that city in many instances where it currently is not.

Both conflicts center on whether Airbnb is a place where hosts “occasionally rent out their homes” while “trying to make ends meet,” as David Hantman, Head of Global Public Policy, wrote in an email this weekend, or if it’s a place where entrepreneurs have turned one apartment or more into a small business.

What Does an Airbnb Host Look Like?

As Airbnb has become more successful, its hosts are looking a lot less like the former and much more like the latter.

The New York Attorney General’s and the San Francisco city council’s moves take Airbnb’s marketing message at face value. In San Francisco, the proposed new law is written so that someone can occasionally rent out their apartment in order to make ends meet, just how Airbnb describes its activity. The proposal limits the number of days an apartment can be rented in a year — only one out of four days — and requires hosts to register their unit with the city. Hosts can only have one listing in the city.

In New York, the Attorney General is not seeking information about hosts who rent out a spare room in their home, or those who rent their place for more than 30 days. The subpoena Airbnb is fighting relates to users who have more than one listing on the site or who rent out their entire home for less than 30 days a month, which is illegal in the state.

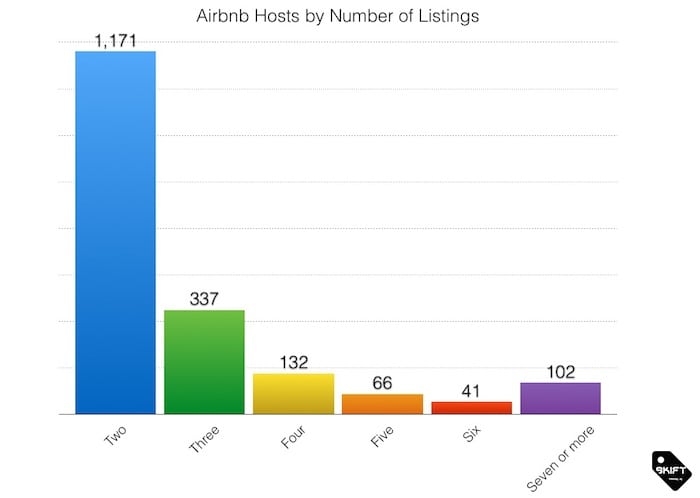

According to research done by Skift and Connotate, 12% of hosts in New York have more than one listing to their name and this represents 30% of the available listings in the city. 102 hosts have 7 or more listings on the site, representing a total of 1,237 available listings on the site.

The Attorney General has filed an affidavit using Skift and Connotate’s research in preparation for its appearance in court on Tuesday. The affidavit is a rewrite of Skift’s coverage of the issue from early February.

Challenging the Airbnb Narrative

In yesterday’s email to Airbnb users, Hantman wrote “The small group of bad actors that abused our platform aren’t part of the Airbnb community anymore, or they are on their way out the door.” The Attorney General responded by releasing a list of many “bad actors” that were still on the site, despite Hantman’s claims.

And even after today’s statement by Airbnb, hosts who have more than one listing are still on the site, including the majority of the ten “super hosts” Skift identified using Airbnb data in January.

Airbnb’s offer to remove over 2,000 listings from bad actors does not represent all the hosts who are renting more than one unit on the site. Out of the 19,000+ listings on the site, those that are run by hosts with more than one listing add up to 5,964.

In Airbnb’s negotiations with the Attorney General last fall, it previously offered to provide the top 40 hosts by gross revenue, where the host did not stay at the apartment. Once talks fell through, Airbnb rescinded the offer, according to court filings.

Tomorrow’s hearing will decide if Airbnb must turn over the narrow set of user data that it requested from Airbnb. Either party could appeal the ruling to the appellate court.

Updated: “Actions speak louder than words,” said Airbnb spokesman Nick Papas. “We did not reach an agreement because, from day one the New York Attorney General has demanded personal information about thousands of regular New Yorkers and that hasn’t changed. Even his ‘revised’ subpoena issued on Friday demands data on thousands of ordinary New Yorkers.”

The Tax Issue

Airbnb’s combative tone the last few days is in stark contrast to the conciliatory tone they’ve had with cities the last two months. Airbnb announced late last month that it wanted New York State law to change in order to allow the service to collect hotel occupancy taxes on behalf of the site’s users beginning in July of this year.

Airbnb estimates that its hosts and users would contribute up to $21 million in tax payments to the city, according to future projections. Currently, as well as through its six-year history, Airbnb has not paid occupancy or hotel taxes that most markets levy on transient guests.

As part of efforts to soothe relations with municipalities, Airbnb wants to pay taxes in San Francisco, Portland, and New York City, and says it is building a framework to make this easy in other destinations as well.

In repeated blog posts, Hantman has said New York legislators are bowing to pressure from the hotel lobby and not revising the law that would let it collect taxes on its users’ behalf. But state legislatures aren’t sure what law Airbnb is seeking to change.

“Airbnb is apparently keeping whatever tax proposal they’re making under wraps, because they haven’t run any language by us and we haven’t seen any new bills introduced or circulated,” said Andrew Goldston, spokesman for Senator Liz Krueger, co-author of the 2010 short-term housing bill Airbnb opposes.

“We hope they don’t plan to splash some money around and then have their bill slipped into a last-second Albany ‘big ugly’ before legislators and the public can review it — a classic insider move that would really go against their branding.”

Response in Albany was not overwhelmingly in Airbnb’s favor, and it appears doubtful that legislation would move fast enough to help Airbnb.

Late last week Hantman authored another blog post that addressed the lack of enthusiasm he’s seen for Airbnb’s proposal:

“We asked leaders to work with us to change the law to permit Airbnb to collect and remit taxes on behalf of our hosts and guests. It isn’t every day that a company offers to help contribute more tax revenue.”

“Our community wants to pay their fair share in taxes and contribute more to New York. A small subset of hotel lobbyists and officials shouldn’t stand in their way. We hope we can all work together to put New York first and we are confident that the vast majority of policymakers in New York will be eager to partner with us to help collect these valuable tax dollars.”

Leaders from New York City’s hotel industry aren’t laughing at Airbnb’s $21 million offer, but they’re not really impressed.

“New York City hotels pay big real estate taxes, big occupancy taxes, and big sales taxes,” says Geoffrey Allan Mills, the Chairman of the Hotel Association of New York City. “It adds up to well over $1.4 billion in value to the city. And that’s before you even count payroll taxes.”

The HANYC represents 275 member hotels in the city which employ over 50,000 staff and manage nearly 100,000 rooms.

Dwell Newsletter

Get breaking news, analysis and data from the week’s most important stories about short-term rentals, vacation rentals, housing, and real estate.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Photo credit: Brian Chesky, Chief Executive Officer of Airbnb smiles during a session at the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos January 23, 2014. Denis Balibouse / Reuters