Skift Take

Life has changed for Icelanders as the country's tourism industry faces a slump. While many are looking at the change as an opportunity to reassess their business, the widespread decline of tourism across the country presents intractable problems.

Down in the icy tunnel, the glacier is sweating. A dozen tourists slip around in the dark, taking selfies and scooping water into bottles from slushy puddles whenever the guide stops walking. Water streams down in thick rivulets throughout, dousing everyone in frigid water.

At the Into the Glacier attraction in northern Iceland, the waves of rapacious tourists snapping up dirty water from a rapidly melting glacier is a stark reminder of the state of Iceland’s tourism sector.

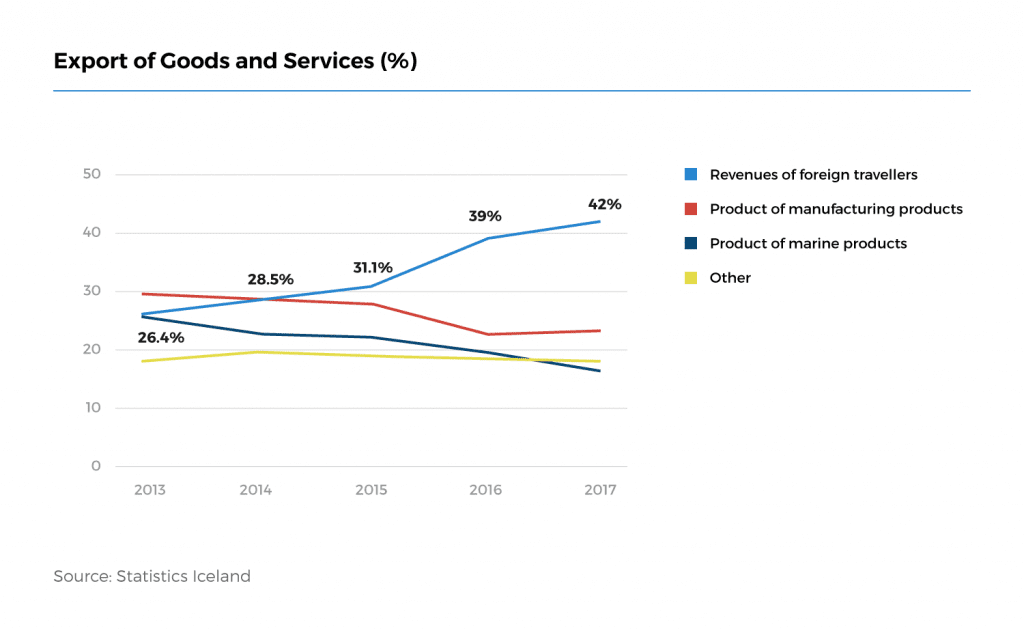

Iceland has been the poster child for the positive and negative effects of the overtourism phenomenon. Tourism growth helped the country recover after a brutal financial crisis and has empowered a new breed of entrepreneurs. Tourism revenue now accounts for 42 percent of Iceland’s economy, an increase from around 27 percent in 2013, according to Statistics Iceland.

With tourism taking on increased importance, the country’s fishing and manufacturing sectors have contracted over time. The change has made the country’s overall economy reliant on foreign visitors.

“It’s never been about the tourists, it’s more about the industry itself,” said Inga Hlín Pálsdóttir, director of Visit Iceland. “After the financial crisis, we were always worried. Are we going into the same bubble? Are we going in the same direction, that this is a bubble that is going to burst?”

Nearly a decade into Iceland’s unprecedented growth as a global tourism hotspot, a variety of issues have led to an economic slowdown that many, surprisingly, see as a good thing for the country’s travel sector.

As the wave of overtourism crested in Iceland over the summer, the country is looking for what’s next. Fortunes have been made and lost over the last decade, with many now looking to the future of Iceland as a more mature tourism destination. Skift returned after three years to Iceland in July, speaking to more than a dozen tourism leaders and residents about the country’s troubles and path forward.

What was different this time was a sense of concern for the country’s overheated tourism industry, What’s more, there is a worry about a malaise left in the wake of an unprecedented boom period that helped bring the country out of an economic recession. Instead of embracing tourism growth, nearly everyone said it is now time for the country to sit back and take stock of how tourism fits into a more sustainable overall economy for Iceland.

The city of Reykjavik remains dotted with cranes as new construction projects have blossomed in recent years. New international shopping outlets, like H&M, have invaded the city at the same time. Generic restaurants and boutiques have popped up, bringing with them new inauthentic locations for travelers to shop and eat.

Many expect these types of projects to be put on hold as the country’s business community grapples with a reality where tourism may not be a reliable cash cow. As Reykjavik has transformed itself into a modern international city, the rest of Iceland may have been left behind. With the lack of a serious cultural backlash against tourism, most have now realized just how crucial the travel sector is to Iceland’s future prospects.

Much in Iceland has changed since Skift visited three years ago. The attitude of Icelanders is now much more cautious, as the business people and small towns lifted up by tourism face the prospect of forging ahead with fewer visitors. Let’s look at how the country got to this point and how its tourism leaders are adapting despite deep uncertainty.

The Big Picture

To understand where Iceland stands today, it’s important to chart the last decade of the country’s evolution following a devastating financial crisis in 2008. Iceland had relied on heavy industries and fishing to power its economy, but over-leveraged banks helped lead to a dramatic drop in the value of the Icelandic krona and led to a rise in unemployment as the country had to be bailed out by the International Monetary Fund.

Tourism in Iceland began to grow following the April 2010 eruption of the Eyjafjallajökull volcano in the country’s south. It was cheap to visit and costs were affordable due to the country’s weak currency; the eruption acted as a global billboard for Iceland’s natural beauty.

Tourism morphed from a minor part of the economy to its biggest industry over the course of the decade.

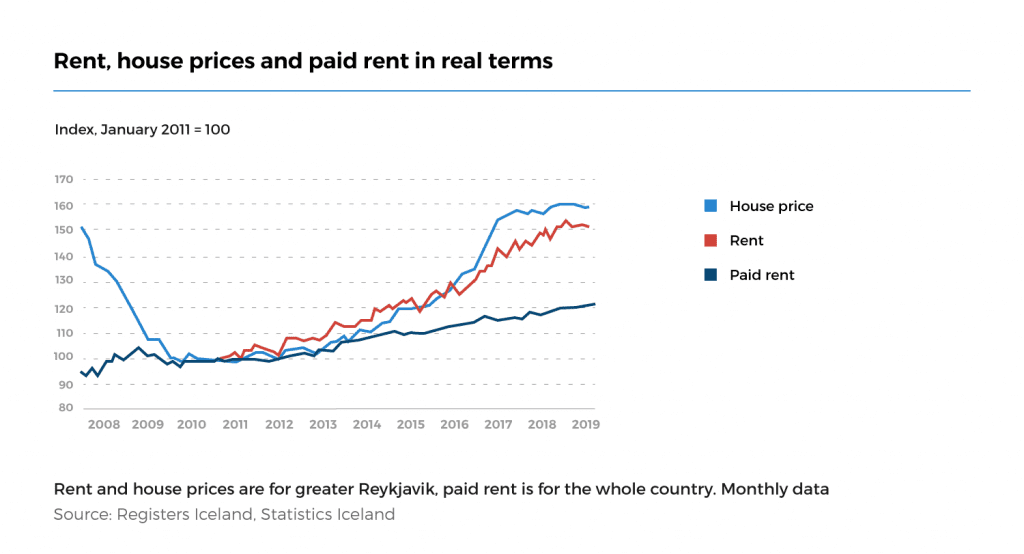

As time went on and its economy recovered, prices began to rise for residents and tourists alike. What was once an affordable vacation became pricier despite the cheap flights that continued to bring passengers to Iceland. Gas and food became pricier for Icelanders, too, putting pressure on households across the country.

“Iceland was in fashion, and the exchange rate of the krona was attractive from the UK, where the boost in tourism really started,” said Magnus Arni Skulason, chairman of Reykjavik Economics, a consulting group. “Tourists from the UK started it, then the U.S., then Germany and other European countries. Post-Brexit, there was a big impact on medium-income Brits who wanted to come to Iceland. And then the appreciation of the krona made it more expensive to come here.”

Now Iceland’s economy is in its first slump since its financial crisis began in 2008. The strong krona, the collapse of Wow Air, the Boeing 737 Max fiasco, and rising labor costs have each contributed to the current downturn.

“We were going down as well, regardless of Wow Air, and that was because the currency was too strong,” said Bjarnheiður Hallsdóttir, head of the Icelandic Travel Industry Association. “It was mainly that but it was a few things at the same time which caused this rather strong decline.”

It’s been a near perfect storm of factors that have led tourism growth numbers to fall and left many Icelanders wondering whether tourism is truly the answer for Iceland’s future. The unexpected collapse of Wow Air in late March helped kick off the massive decline in tourism; tens of thousands of passengers who were planning to visit Iceland on the cheap can simply no longer visit.

The last time international visitation dropped so steeply? The month following the eruption of Eyjafjallajökull, which led to the cancellation of 95,000 flights in Europe and Iceland. This crisis is manmade, though.

Statistics don’t bear out a catastrophic collapse of Iceland’s tourism sector. Far from it, in fact; tourism in 2019, so far, has fallen to 2017 levels, according to leaders across Iceland’s tourism sector judging by their businesses. The full picture won’t emerge until the end of the year, when Iceland enters the shoulder season for its tourism industry.

The latest tourism accounts from Statistics Iceland show what tourism executives have noticed in their own businesses. In June, the beginning of Iceland’s busiest traditional tourism period, tourist visitation dropped by 15 percent year-over-year. Tourism VAT turnover dropped 12 percent, mimicking the visitation drop.

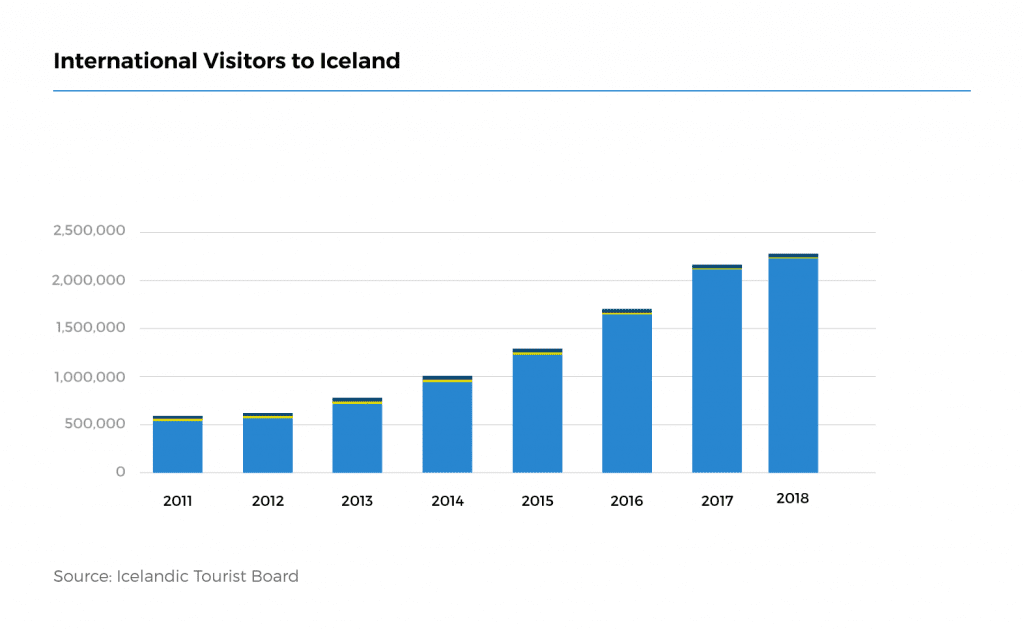

To put a potential 15 percent decline into perspective, Iceland experienced 5.4 percent growth in international visitation in 2018 and 24.1 percent growth in 2017 according to the Iceland Tourist Board. So a 15 percent decline over the next year would bring visitation back to 2017 levels, which represents a 400 percent increase from 2011 visitation levels.

A few wrinkles emerge that show how the slowdown is affecting the types of vacations people are taking. Hotel stays were flat year-over-year in June, while Airbnb stays dropped 11 percent. Unpaid accommodations, like camping, declined a massive 30 percent, presenting more evidence that Iceland’s tourism economy is shifting away from affordability to a more expensive and upscale proposition for travelers.

Iceland’s hotel sector has been built up during the boom, growing 9 percent in number of rooms from July 2014 to July 2019, according to STR. Seven hotels totaling another 1,129 rooms are in the country’s pipeline, and many in the tourism sector are concerned those properties will be shelved if economy uncertainty persists. Strong regulations against Airbnb, limiting rentals to 90 days each year, have also decreased the ability of travelers to use homesharing services.

Still, housing in Reykjavik remains incredibly more expensive than elsewhere in the country.

The flip side is that tourism’s growth outside of the Reykjavik area, which has helped revitalize sleepy towns and empowered entrepreneurs to build businesses, is perhaps most severely affected by this slowdown.

Vehicle traffic around Iceland’s ring road has decreased across all of the country’s regions, with East and West Iceland seeing double-digit year-over-year declines in July. All those remote villages and fishing towns which rode the wave of increased tourism are now feeling the effect of fewer visitors during the peak summer travel season.

“In a way this growth was unexpected and then too much,” said Hallsdóttir. “But on the other hand, we have a lot of new investment and new companies which are suffering right now because of that. For the long term thinking, it’s good that we have a little break now regarding the tourism infrastructure. And then I’m talking about the public sector. The private sector is ready and was ready when the big boom came, but the public sector wasn’t.”

Air Trouble

While the collapse of Wow Air helped touch off the downturn, the struggles of national carrier Icelandair over the last year bear some responsibility as well.

Wow Air, the low-cost carrier launched by entrepreneur Skúli Mogensen in 2012, eventually grew to a 20 plane fleet before economic trouble hit in 2018. New widebody planes increased its operating costs and the airline had trouble filling the extra seats on these planes. The airline began to lose money before collapsing into bankruptcy on March 28, 2019 following a failed acquisition by Icelandair.

The collapse immediately made it more difficult and expensive for U.S. travelers, who account for about a third of total visitors to Iceland, to visit this year. High costs already deterred U.S. visitors with 7.1 percent fewer visiting from August 2018 to July 2019 than in the previous year.

Chinese visitors continued to surge 14.8 percent over the same period while top European destinations except for Poland declined. Chinese visitors also spend the most of any traveler, likely helping stanch some of the bleeding from the widespread decline in tourism.

At the same time, rival Icelandair was beset by its own problems. It was forced to lease aircraft after grounding its fleet of nine Boeing 737 Max aircraft, leading to a decline in capacity and increased costs as the summer travel season began. Strong competition from European carriers also limited its ability to grow airfares in 2018, causing it to lose money.

It sold off 80 percent of its Icelandair Hotels division to Malaysian investor Vincent Tan as part of a plan to focus solely on air transportation and tourism operations.

“The MAX aircraft were intended to cover 27 percent of Icelandair’s passenger capacity in 2019,” said Icelandair CEO Bogi Nils Bogason in a recent earnings report.” For this reason, the position in which the company now finds itself as a result of the suspension of the MAX aircraft is without any precedent and has a significant impact on the operations and performance of the Company… We have also placed emphasis on ensuring seating capacity to and from Iceland, with the result that the number of Icelandair’s passengers traveling to Iceland has increased by 39 percent in the second quarter compared to the same period last year.”

The loss of Wow Air, then, has helped to boost the future prospects of Icelandair once the Boeing 737 Max situation is sorted out.

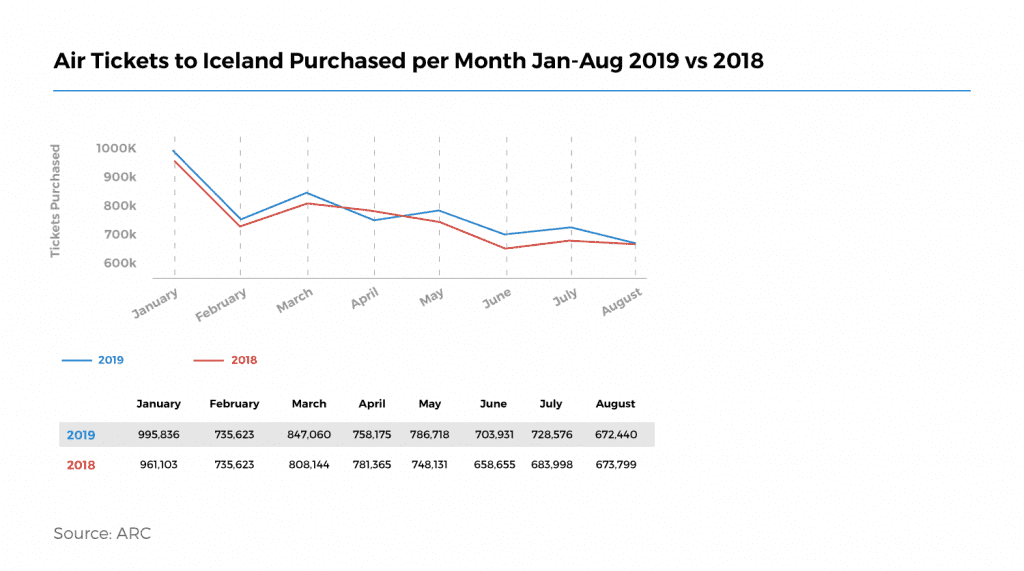

The growth of both airlines essentially eliminated seasonality for Iceland’s tourism industry, and a lasting disruption is likely to bring it back in a major blow to the sector’s less established players. An analysis by Airlines Reporting Corp., which provides services to most global passenger airlines, found that its partner airlines have actually sold more tickets to Iceland in 2019 than 2018, presenting some hope that the downturn will be limited in scope.

“Both Icelandair and Wow Air were adding seat capacity during the winter,” said Sveinbjörn Indridrason, managing director of Isavia, Iceland’s airport authority. “Last year there was no seasonality in Iceland. So you had this summer traffic three months, these shoulders four months and then the winter traffic five months. Similar distribution passenger-wise, not per passenger. So the seasonality just went out of the Iceland market.”

A side effect of the decline in flights has been the limited ability for Icelandic goods to reach global markets, injuring economic sectors outside of tourism in the process. International cargo shipping has increased from 35.2 million tons in 2010 to 57.4 million tons in 2018, broadening the ability of Icelandic companies to sell goods in foreign markets.

For what it’s worth, the hub strategy which helped power the growth of aviation in Iceland is still being pursued by Isavia. While the company’s master plan from 2015 did not anticipate the massive surge in new routes and arrivals, this downturn is helping to bring the sector back to its original projections.

“When Wow Air went bankrupt it was not bad timing if you look at it from a construction perspective,” he said. “So we are not in the middle of any real construction so we don’t have to lay down any hammers and have like a half-built terminal building with a lot of invested costs but maybe not the revenues to finish it.”

Indridrason confirmed that he had been contacted by representatives of WAB Air, which had designs to restart Wow Air’s operations in the near future as an Icelandic company, and American investor Michelle Ballarin who purchased Wow Air’s assets following the bankruptcy. In early September, Ballarin announced her plans for Wow Air to begin service once again over the next year although experts are unsure of how realistic her timetable is.

“There’s a reason Wow Air failed the first time,” said Jay Shabat, senior analyst at Skift Airline Weekly. “There was simply too much capacity in the market and what’s known of the plan to revive it doesn’t inspire much confidence.”

There have also been rumblings of the potential for a new international airport near Keflavik to help supercharge tourism growth and the country’s cargo business. It’s a thorny political issue, but Indridrason noted there would be many challenges faced by operating two busy airports so close to each other.

Even if the government wanted to close Keflavik and operate a single international airport, the U.S. Navy’s base at the airport complicates the matter.

Perhaps the biggest opportunity to grow tourism would be through a more robust network of regional airports across the country. Right now, tourists are forced to transfer from Keflavik to Reykjavik City Airport, nearly an hour away, in order to fly into one of Iceland’s smaller domestic airports.

Many proponents of increased tourism across Iceland believe an increase in domestic flights from Keflavik would help boost the industry as it spreads across the country. Right now, direct flights are available for tourists from Keflavik to Akureyri in Northern Iceland but not to other areas. Besides occasional charter flights direct from international destinations that already happen, a more robust series of routes and airports have the potential to boost future growth.

“If you need to build infrastructure that can handle serious international traffic [in these smaller regions], it would be very costly and will probably never be profitable,” said Indridrason. “The domestic airport system, it’s a public transportation system funded by the State of Iceland. And public transportation always needs to be funded by the municipalities or the individual States. But you can’t combine those things if you don’t bring [travelers first to boost the economies in those regions].”

Tour Operator Woes

Part of the problem is that many emerging tourism companies acted to take advantage of the boom by growing quickly instead of taking a more measured and conservative approach.

Travelers are still spending on package tours when they visit, despite flights and accommodations eating up a more significant portion of travelers’ budgets, according to data from the Iceland Tourist Board.

While travelers continue to spend, the margins operators are likely to have shrunk.

“Wow Air went down in April, and that obviously had an effect,” said Hjalti Baldursson, CEO of Reykjavik-based tour operator technology company Bokun, which is owned by TripAdvisor and operates the technology backbone for most tour companies in Iceland. “There was a small decrease in May. April was 1 percent up year-on-year, but other months are up significantly in terms of booking numbers. That doesn’t tell the story of whether the companies profitable, because if you look at the average order value measured in dollars that is going down quite significantly. This has to do with currency fluctuations between the Icelandic króna and the U.S. dollar.

“The margin of the companies that are selling is going down. On top of this, there is big competition in Iceland. There are more and more companies coming into the market that are providing good products.”

Bokun’s data also show an increase in direct online booking, meaning operators pocket more of a booking’s value, increasing the margins on their products in the process. The cost of labor, though, presents a major challenge to tour operators operating on thing margins.

“Another thing influencing companies in Iceland is that salary costs are going up,” said Baldursson. “Iceland has been coming off its own success, the economic metrics of the country are extremely good. It’s a very healthy economy and in all measurements a rich country. So getting staff and competing with lower paid staff in other markets is becoming harder and harder.”

Evidence backs this claim up. Iceland has the fifth highest gross domestic product per capita among European countries, and the country’s wages increased 6.7 percent from 2016 to 2018. The country’s strongest unions also recently locked in a wage increase, putting more pressure on low-margin businesses. Even with seasonal workers from other European countries working during peak periods, the cost of labor remains a major obstacle to growth.

The economic contraction is leading to a wave of consolidation in Iceland’s tour industry. On Skift’s last trip to Iceland three years ago, we spoke to Hjörvar Sæberg Högnason, who had founded tour operator Reykjavik Sightseeing in order to appeal to the new wave of international visitors to Iceland.

Since then a race to the bottom on pricing coupled with rising labor costs and the high value of the krona have caught up to Högnason. Competition with the established Gray Line Iceland and Reykjavik Expeditions, the other two major bus tour operators in Reykjavik, had led the company down an unsustainable path once signs of a tourism slowdown began to emerge late last year.

An effort to grow his business by partnering with Blue Lagoon for the spa’s shuttles, and earning the concession for Keflavik’s city shuttle to Reykjavik, also proved challenging with respect to low margins and the complications of running a bus tour operation alongside shuttles.

In an effort to compete going forward, Gray Line Iceland and Högnason’s Reykjavik Sightseeing announced a merger earlier this year to provide a competitive advantage against Reykjavik Expeditions.

“There’s increasing talk of companies needing to merge,” said Högnason. “We’re nowhere near a catastrophe; the situation gives us the time to step back and run our businesses in a more economic fashion.”

He also noted that self-guided tours and the ease of renting a car likely contributed to a downturn in business for bus tour operators. A recent report suggests 80 percent of visitors to Iceland rent a car at some point in their trip.

“Year-round, we think there will be more car rentals on the road,” said Högnason. “You have all the international car rental brands and local ones; I’d imagine they are in a bidding war for travelers right now.”

In the rush to compete over the last three years, money was invested in growing his fleet and branding at the expense of innovating in the actual tour experience. Finding skilled, qualified guides remains a challenge particularly as Iceland’s tourism sector continues to mature.

“We need to do it extra well, in a way that makes people excited to come back the next day,” said Högnason. “The agenda is to teach travelers how to behave and embrace the traveler experience. There is decreasing demand, so let’s make sure they leave with a positive impression.”

Much like Wow Air couldn’t survive a blip in demand after a potential merger with Icelandair was tabled, so too are tourism companies consolidating in order to better weather this uncertain period. A return to strong growth instead of the explosive growth the country has seen this decade will ensure that business practices shift and become less risky for operators and their employees.

“It is quite easy to run a company if your business is growing 50 percent,” said Baldursson. “Then you’re typically worried for the customers and not the operational efficiencies. Now when we’re seeing small double digit growth, maybe, as for example, in July we saw a 15 percent growth, in June we saw a 7 percent growth in number of bookings. We’re seeing that companies have a tendency now to look more into their costs and cost base. It’s an opportunity for them, and I think it’s a healthy revamp of their operations that they’re running through right now.”

Another wrinkle could spell future trouble for Iceland’s tour sector: the quiet rise of cruising in ports across Iceland. Overall, the number of cruise ships entering port has increased from 476 in 2016 to 750 in 2018, according to Cruise Iceland. Passengers arriving in port grew from 326,850 to 441,789 over the same period, a 35 percent increase in the number of potential visitors to Iceland’s port cities.

Cruise passengers tend to cause congestion at a city’s most popular attractions without contributing much to the local economy.

The biggest beneficiaries have been not just Reykjavik, but the smaller cities across the country that see few international visitors from tours and domestic flights. With the high costs associated with a trip to Iceland expected to remain, a more affordable cruise vacation is becoming a compelling option for vacationers.

“Above all the ports are happy about it,” said Hallsdóttir, head of the Icelandic Travel Industry Association. “Some of the smaller communities in the rural areas very far away from Reykjavík, they are getting some business at least. This is a topic we have to really have to think about and regulate before it gets over our heads.”

Something for Everyone

As a tourism hotspot matures, it tends to lose some of the authenticity that made it attractive to visit in the first place. Iceland, too, with its ample natural beauty and unique culture isn’t immune to the forces of globalization, as evinced by the transformation of Reykjavik into something resembling a traditional international city.

As investment dollars have flowed into tourism, new attractions have been under development that wouldn’t be out of place in any major travel destination around the world. The difference is that these attractions are being designed for not just travelers, but native Icelanders as well.

One example is Perlan, a landmark overlooking Reykjavik which has been converted into a museum and restaurant with stunning views of the city. A dome built around six water tanks, the building used to house a rotating restaurant on its top floor. Today, the building attracts visitors during the week and Icelanders on the weekends.

By appealing to locals instead of just tourists, the somewhat strange attraction has found new life in an Iceland where the new can coexist with the old.

“Flying is now more expensive, and accommodations are more expensive; Southern hotels aren’t fully booked,” said Eva Björnsdóttir, the reception manager at Perlan, of the country’s prospects amid a tourism decline. “Icelanders need to come together and help each others’ businesses. We need to make sure that travelers have a good time, not just in one place, but across their entire trip. They’re competing for the same guest. We need to think of Iceland as a whole experience for travelers.”

Another newcomer to Reykjavik is FlyOver Iceland, a mixed media experience where visitors go on a virtual flyover around Iceland’s most scenic landmarks.

On a hard-hat tour of the attraction in the final stages of construction, it was clear Flyover Iceland could exist in any major tourist destination; the concept, created by the Canadian company Pursuit, already has similar operations in Toronto and Las Vegas.

“A lot has happened in the tourism sector over the last year,” said Eva Eiríksdóttir, manager of marketing and brand experience for FlyOver Iceland. “It has cooled down and people were panicking, but the slow down is probably a good thing.”

Eiríksdóttir pointed out that the weather is often bad in Iceland, increasing the demand for indoor activities like FlyOver Iceland for visiting families and residents. With high property values and rent prices in downtown Reykjavik as well, new attractions could provide the impetus for the development of new neighborhoods and communities too.

These types of attractions aren’t just popping up in Reykjavik, though. New spas, attractions, and experiences are popping up in the country’s North and South regions, offering a blend of Icelandic culture and modern convenience. One of the most absurd is 1238: The Battle for Iceland, a virtual reality experience that puts visitors inside a variety of historical viking battles.

The attraction is located in Skagafjörður, which sits about 3 hours by car from Reykjavik and 90 minutes from secondary city Akureyri, showing how regions outside Iceland’s capital have benefitted from the tourism boom.

Instagram and Its Discontents

Speaking with tourism experts and locals alike, concerns about the damaging effects of increased tourism on Iceland’s environment were minimal.

Iceland is a victim of climate change like so many places but has chosen to focus on sustainability in the areas it can control, like traveler behavior and waste management. A major campaign to encourage visitors to drink tap water instead of bottled water, for instance, has found success this year as news of the demise of Icelandic glacier Okjokull entered global headlines.

Specific cases of overtourism, though, gravely concern many who have tired of people exploiting the environment for profit.

Many tie the rise of social media to the growth of Iceland’s tourism sector in an integral way, and it’s difficult to see a way out.

“There’s an issue with locations and the number of people visiting them,” said Joe Shutter, a Reykjavik-based photographer who leads small group photography tours across the country. “You can have a well behaved visitor and a not very well behaved visitor. They both have two feet. There is a certain critical mass. There’s a scale transformation that takes place. Location A: 10 people visit. Location B: 100 people visit. The damage is more than ten times worse on location B. Damage goes up exponentially. Some places literally cannot handle it.”

He gave an example of an Instagram influencer who had recently posted specific information for travelers to visit a remote and beautiful location he shoots at, replete with geotag information. When he asked the influencer to remove the geotag, the influencer simply said it would violate their ethics to do so and updated their caption with a warning for travelers not to litter or damage the location.

“This is the absolute lowest common denominator of how anybody should behave with a modicum of decorum in a location,” said Shutter. “I explained to them that two feet are two feet. And a hundred feet are worse than ten. And that a scale transformation takes place with that and that means that behaviors have to be modified in that sense in that certain places literally can’t handle that.”

Others say it should be up to the government to select specific places to protect instead of residents working to limit what areas that tourists can access. The Icelandic government has some of the strongest sustainability standards in Europe, but has been hands off when it comes to limiting where tourists can visit.

“If it’s a natural site and it has to be protected then there has to be a protection put on that area and with that comes regulation,” said Katarzyna Maria Dygul, who works with Visit Iceland on public relations and social media. “You can also put a quota on that, like you have all around the world a quota of how many people can visit a location because of that. Or when there’s vegetation, then the local authorities also have to understand that with the growing number of people they will have to adjust. People will not be able to go all the way on that vegetation but instead there will be a viewing patio or platform. That’s fine because… half a year later, other people who come will never expect to go on the grass. They will expect to stand on the platform.”

Dygul and Shutter are co-owners of The Space, a co-working space and art studio in downtown Reykjavik that wouldn’t be out of place in Berlin or Brooklyn.

This tension was also present during Skift’s earlier trip to Iceland. Many who are concerned about the effect of increased tourism on the environment and roads, for instance, also believe that increased fees or restrictions will drive away the travelers the country needs to continue its strong tourism growth.

It’s one thing, though, to appeal to the individual values or ethics of the individual traveler and encourage them to drink tap water or avoid driving their truck off a cliff. It’s another to curb the damage caused by social media’s herd mentality.

“The big group of people who come here are millennials,” said Dygul. “This is a group generally that is more empowered to do things on their own. We work with influencers all the time and it’s very easy to filter out those people who maybe have a large following and stunning content but basically the same content as everybody else… when you have another few hundred thousand people that do not know anything about photography but they want to take the same picture, you’re suddenly in a very different dilemma.”

The line between being a beneficiary or a victim of social media is slim in the age of overtourism. With Iceland’s tourism growth in doubt, it’s possible that the need to attract tourists will outweigh calls to limit tourism and its damage to the environment.

Others, though, have a more conservative vision for the future of tourism in Iceland. In the town of Húsafell, about 90 minutes from Reykjavik, sustainability and hospitality merge in a manner that attracts both international tourists and Icelandic families.

The small town is a destination for Icelanders looking to camp, and the family which owns the town built Hotel Húsafell to cater to the growing cadre of international tourists in 2015. The town also operates as a jumping off point for glacier and lava cave tours. There’s no Instagram bait, save for the mountains in the distance where Icelandic strongman competitions once took place.

The small hotel is popular with families and groups who tend to stay for just a day or two on their vacation, according to Kristján Guðmundsson, marketing manager for Hotel Húsafell. China is a major source market. During slow periods and the shoulder season, the property offers Icelander-only rates to increase demand. The small stature of the hotel, and popularity of Húsafell as a camping destination, make it less likely to be severely impacted by reduced tourism demand.

The hotel and the entire town is powered by sustainable geothermal energy, as well, with food from local fisheries and farms. The ownership is considering building a spa for international visitors, and is currently building a bath in a perilous, but scenic, valley nearby.

Húsafell is just one example of many Icelandic towns that have taken a more measured approach to profiting off the tourism boom. Those who grew more slowly during the boom years seem better positioned to survive the current downturn.

Uncertain Times

In many ways, it is likely a slowdown in tourism will help Iceland’s tourism industry become not just more stable, but more sustainable. While the future of Iceland’s tourism sector remains murky, the bottom hasn’t fallen in the first few months of the downturn.

It may be time for the Icelandic government to finally make a concerted effort to prepare for Iceland’s future as a beacon for tourists, particularly if its other industries continue to struggle. With limited growth expected from its flagging fishing and manufacturing sectors, leaders need to articulate a vision for the country that goes beyond becoming more hospitable to foreign guests.

The lack of a major backlash against tourism has led to the lack of a cohesive government policy to oversee its growth. There is something of a vocal minority, as one source put it, but those people are simply annoyed at seeing more tour buses and rental cars driving by their farms.

“The government is going to finish a new tourism strategy,” said Hlín Pálsdóttir, director of Visit Iceland. “Like probably everywhere else in the world, the main focus is on sustainability. How can we be sustainable? Because what has not been that much discussed is how important tourism has been for the regions. Many people are actually moving back to their hometowns, And they didn’t really have that opportunity a few years back.”

The good news for environmentalists and those concerned with the environmental impact that overtourism has had on Iceland is that the slowdown will reduce the effect of tourism in the short term. It may limit domestic investment in the country’s tourism infrastructure, though.

“Some of the tourism sites need more investment; we have to regulate the traffic, the tourism flow in certain areas,” said Hallsdóttir, head of the Icelandic Travel Industry Association. “There has been a lot more consciousness from the public sector in the last two, three years. They know now what they have to do and are willing to do it. So I think we will cope. That’s my strong belief… We are hoping to get in line with the normal growth, which is about 4 or 5 percent per year. Not these crazy numbers from a few years ago.”

With tourism growth tailing off, Iceland needs to look to the future. Relying on tourists to boost its economy worked for nearly a decade, but leaders need to search for methods to build a more stable environment for workers and entrepreneurs.

Tourism is an export that is highly susceptible to shifts in both supply and demand. With a global recession likely on the way in coming years, even a quick recovery for Iceland’s tourism industry may leave its overall economy in a rut should global tourism decline.

Perhaps the lesson from the end to Iceland’s tourism boom extends beyond tourism itself: it’s time to take action during a crisis instead of waiting for another miracle.

The Daily Newsletter

Our daily coverage of the global travel industry. Written by editors and analysts from across Skift’s brands.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: deep dives, iceland, overtourism

Photo credit: The Blue Lagoon in Grindavik, Iceland. Chris Ford / Flickr