Skift Take

As destinations scramble to reduce the impact of tourism on their citizens, foundational work must still be done to create a repeatable framework and process for preventing overtourism.

The world is in an unprecedented period of tourism growth, and not everyone is happy about it. Arrivals by international tourists have nearly doubled since 2000, with 674 million crossing borders for leisure back then and 1.2 billion doing the same in 2016.

As the travel industry has ramped up its operations around the world, destinations have not been well-equipped to deal with the economic, social, and cultural ramifications. Cities have often made economic growth spurred by traveler spending a priority at the expense of quality of life for locals.

Europe has been perhaps hardest hit by the stress of increased travel and tourism. Barcelona, Venice, and Reykjavik are just some of the cities that have recently been transformed by visitors.

For the last few months, news reports have reflected the truth about the global travel industry: Not enough has been done to limit the negative impact of tourism as it has reached record levels in destinations around the world. Anti-traveler sentiment is seemingly on the rise.

“I would consider [these cities] to be canaries in the coal mine,” said Megan Epler Wood, director of the International Sustainable Tourism Initiative at the Center for Health and the Global Environment at the Harvard School of Public Health. “The folks that have been protesting are from highly visited destinations and they don’t feel their lives should be interrupted by tourism.”

She continued: “They’re in a position of making a statement… something I’ve been discouraged about is the idea that people who are protesting are making a mistake. It’s important they make a statement because we need to hear from them and come to a new level of understanding of what this means. We need to very seriously find what their concerns are and figure out how to plan with those destinations and think about acting proactively.”

Why have some destinations thrown up their hands in helplessness in dealing with the deluge of tourists? And what have other destinations done to successfully limit the effects of increased visitation?

Skift has identified five solutions to overtourism, drawing from what destinations have done successfully to limit the influx of tourists, and we spoke to global tourism experts about their perspectives. We also looked at the ways in which travel companies themselves have been complicit and what more they can do to grow global tourism in a more sustainable way. We don’t argue that these are one-size-fits-all solutions for every trampled-upon destination, but they may serve as a solid foundation for beginning to tackle the problem.

Furthermore, we look to the future for ways in which the travel industry, in conjunction with local stakeholders, can better measure and limit the adverse effects of tourism.

If the travel industry can help connect the world and build bridges between cultures, why has it struggled to find a sustainable path forward?

1. Limiting Transportation Options

Travel has become more affordable over the last decade, particularly in Europe and developing economies in Asia with the rise of the middle class. Low-cost carriers have proliferated, while megaships from cruise giants have extended their reach around the world.

Various indicators show that more flights are taking place across Europe than ever before, particularly during the busy summer vacation season.

“[Increased travel has] been controversial in a way that is directly due to the fact that businesses arrive in a city and disrupt normal life and commercial activity,” said Tom Jenkins, CEO of the European Tour Operators Association. “In fact, cities are designed for tourism to disrupt normal activity, because tourists are not normal by definition in how they behave. They’re always disruptive and it’s always been controversial. Even if your city becomes rejuvenated, when you get foreigners arriving somewhere exerting financial influence over supply, you get a phobia.”

Why have some cities with pervasive tourism, like Paris, not had the same recent backlash as Barcelona or Berlin?

Jenkins notes that backlash against tourism is a consistent theme throughout European history; people said the same thing about the advent of railways and steamships warping the character of their cities that they do today about cruises and cheap flights.

Let’s take a look at Barcelona’s struggles with increased visitation in recent years. Data from IATA, MedCruise, and Visit Barcelona expose the massive influx of visitors to the city.

The increase in cruisers is particularly striking. Since Barcelona really hit the world stage thanks to the 1992 Summer Olympics, its cruise traffic has gone from about 100,000 cruisers in port to about 2.7 million in 2016. In the greater Mediterranean, the average number of passengers per call has increased from 848 in 2000 to 2,038 in 2016.

| Top European Cruise Ports (in passengers) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Passengers | 2016 | Passengers | |

| 1 | Cyprus Ports | .08 million | Barcelona | 2.7 million |

| 2 | Balearic Islands | 0.6 million | Civitavecchia | 2.3 million |

| 3 | Barcelona | 0.6 million | Balearic Islands | 2 million |

| 4 | Piraeus | 0.5 million | Venice | 1.6 million |

| 5 | Istanbul | 0.4 million | Marseille | 1.6 million |

| 6 | Genoa | 0.4 million | Naples | 1.3 million |

| 7 | Naples | 0.4 million | Piraeus | 1.1 million |

| 8 | Civitavecchia | 0.4 million | Genoa | 1 million |

| 9 | Venice | 0.33 million | Savona | 0.9 million |

| 10 | French Riviera | 0.3 million | Tenerife Ports | 0.9 million |

| Source: MedCruise |

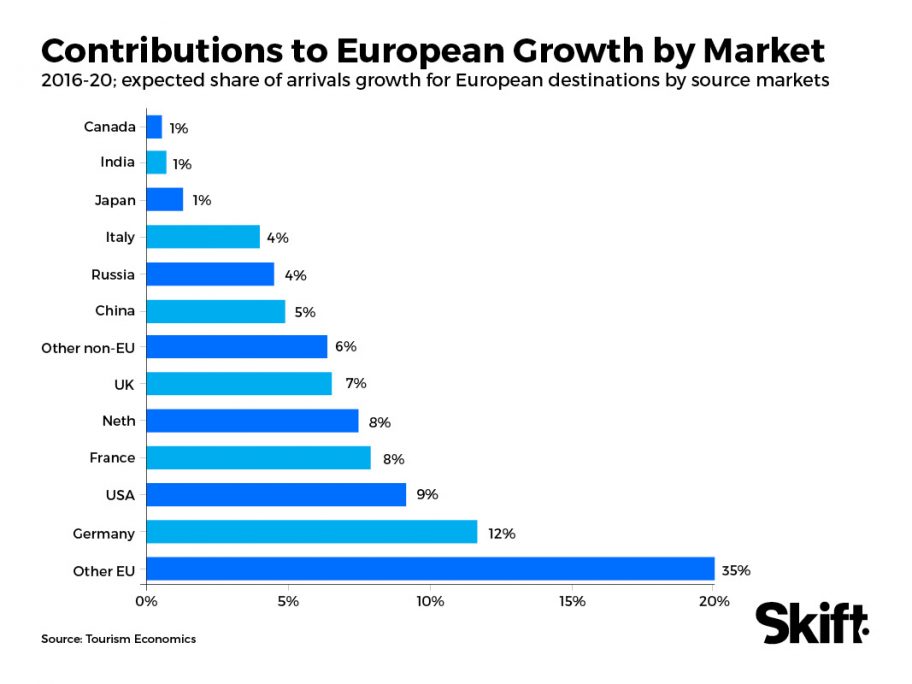

The impact of low-cost carriers, along with the relative strength of the euro in recent years, has also played an important role. While there has been a major focus on the influx of U.S. and Chinese tourists to Europe, evidence suggests that the most frequent visitors are actually from European countries. Indeed, according to surveys from Visit Barcelona, European tourists comprise around two-thirds of those visiting the city.

It follows that if cities and tourism boards would work to make it more difficult to access their destinations, by limiting cruise ship tenders or the access of low-cost carriers to airport terminals, that fewer visitors would be able to come.

There’s also a bit of a contradiction here: Often residents of areas that have been built up and developed by tourism blame the travel industry, and not their politicians and city planners, for the changes.

https://vimeo.com/226440841

Boorish tourists become a target for protests and outcries, instead of the local and regional forces that have more or less enabled their ability to visit a destination en masse.

“The moment you start meddling with things, you affect the economic pattern of the town, and all kinds of problems arise,” said Jenkins. “There is a quite startling depiction of giant cruise ships in Venice, but someone gave permission for that at some point. Someone is taking their money. Someone with power and discretion said, ‘You come and park here.’ Similarly in Amsterdam, the inhabitants are very resentful, but the visitors didn’t organize their red light district and permit cannabis shops to open. The residents did. It’s just bonkers and it’s a planning problem, not a tourism problem. It has a planning solution.”

Amsterdam has recently restricted new tourist shops in its city center, a solid first step. The city is still struggling to cope with the effect of rampant homesharing.

Urban dwellers across Europe have announced their anti-tourism sentiment in various ways. Stakeholders should be looking forward and planning to craft a more equitable environment for both tourists and locals, even if it means reducing tourism and those who have built successful businesses serving them.

An easy way to do that — well, nothing seems especially easy when it comes to this issue — is to simply make it harder to visit instead of creating restrictions when travelers are already in destination.

2. Make It More Expensive

Travel has become more of a commodity purchase for consumers than an occasional luxury in recent years, spurred by low-cost carriers and affordable homesharing services.

“[Managing tourism] is a good thing to be talking about because our industry is good at selling the virtues of tourism, but we’re not very good at being honest with ourselves about what we do well and what we don’t,” said Darrell Wade, co-founder of Australia-based Intrepid Travel. “In some ways, the industry hasn’t progressed at all. There are nice towns [all over the world to visit], and you look at places like Croatia where there are several hundred islands, towns, and villages. There’s lots of great stuff to do, so let’s get out of the tourist area in Dubrovnik.”

Countries that suffer currency devaluation are also extremely susceptible to a tourism rush, as in the case of Iceland. We’re seeing this now in London following the Brexit vote, as well.

In recent years, Iceland has moved to offer more luxury accommodations and experiences in a bid to attract higher-yielding travelers as the country’s currency has rebounded from a crash in 2008.

Even if mass market tourism slows down due to increased costs, dropping Iceland’s annual tourism growth rate from around 30 percent to 10 percent, the cool-down would be beneficial for locals struggling to deal with rising cost of goods and a hot property market in Reykjavik.

When Skift went to Iceland last year, the country’s top travel and tourism executives told us the most attractive way to slow down growth is to create more luxury offerings for higher-spending travelers. As gentrification hits major cities worldwide, this can sometimes happen as a result of investment and real estate speculation.

Adventure and luxury tour operators and cruise lines are better positioned to provide experiences outside of the traditional tourist areas in a destination.

“Most of our departures are to the remote destinations, but we have quite a bit of presence in some of that heavily trafficked area [in Europe],” said Trey Byus, chief expedition officer at Lindblad Expeditions. “We take a different approach to that. The east end of the Greek islands is one of the most overrun places in terms of tourism, so we don’t go there during the busiest of seasons, we’ll go on the shoulder seasons. You take a look at the islands and there’s the obvious places where the mass tourists go where we avoid, places where the Greeks would go to holiday….We’ve been in the Adriatic for many years and at one point many years ago we considered a turnaround in Venice, but even then we said we’re not going to go there. That’s going to provide an awful first and last experience for us, so we took that off the map.”

There’s also the question of demand management, which few destinations have embraced in a significant way. Similar to the way attractions like Walt Disney World charge more for tickets during peak periods, destinations can increase the ticket price to access areas when demand is the highest.

Barcelona is considering a tax on tour operators to make it more expensive for tourists to visit, for instance, and the city already taxes hotels, apartment shares, and cruise ships. Perhaps a more concerted legislative effort to make visiting more expensive can replace mass tourism with higher-spending and more respectful visitation.

This would, in theory, at least, not only generate more revenue for cities to deal with the myriad complications of overtourism, but condition tourists to visit during periods of decreased demand when their impact on locals would be more limited. Over time, perhaps, tourists can be trained to be more thoughtful about their travel decisions. At the very least, life for locals would improve.

“What you see looking forward is obviously demand seems to be growing exponentially and you see more and more pressure,” said Jenkins. “Can they tweak capacity in a way that things can be spread out, and that the demand can be managed and controlled through price? I’m absolutely convinced. We’re seeing a huge increase in capacity in some places, can they carry on doing so? They probably can, given there is demand for them and money to facilitate that demand.

“There’s also the scope for demand management. People think if the price goes through the roof, they won’t have to manage the attraction. People will have to get used to paying more to visit peak attractions at peak times. The way we price things [in the travel industry], there’s no incentive to alter your arrival at all. It’s all the same price.”

Many remote destinations do a form of this with permits, only allowing groups of visitors in a few times a day. The Galapagos Islands, Machu Picchu, and others have embraced this form of demand management for decades. Urban destinations could take a page out of their playbooks by limiting access to high-demand areas and increasing the price of access at the same time.

3. Better Marketing and Education

There seems to be one issue that few destinations have figured out: How do you keep tourists from wrecking the environment or crowding cities?

Better education, and more realistic marketing, can help. Gone are the days where famous historic monuments like the Spanish Steps or Kensington Gardens will be accessible without a horde of tourists, and travel companies selling affordable tours need to do a better job of letting tourists know what they’re really buying.

London, for instance, has laid out a plan into the next decade to manage tourism growth, and it includes marketing its outer areas to tourists instead of downtown or Westminster. New York City unveiled a similar plan last year, looking to capitalize on increased tourist interest in Brooklyn.

If tourism companies sell travelers vacations based on certain promises, like deserted beaches and town squares, it can be a problem if their experiences don’t match expectations.

“I see it as everyone’s problem; some organizations are the source, like national tourist authorities, airlines, and cruise lines,” said Intrepid Travel’s Wade. “Part two is the traveler, because they’re a little on the lazy side and they don’t realize the image they saw online of a destination has 100,000 people in it in real life. This isn’t great for our industry either, because it’s a terrible product. I walked around Dubrovnik [recently], and I’m not enjoying it. We want to empower people and change how they think about the world. We don’t want to be sending them to hellholes, it’s not in our long-term interest.”

From an education standpoint, travel stakeholders have to present their products more realistically. They also have to educate their customers on what they’re really getting into on a trip, and the acceptable ways to behave while in-destination.

If travel is really about experiencing a distinct culture, then travelers should be prepared to respect localities and traditions; travel can’t just be a commodity. Some travelers, though, just want to relax on a beach somewhere with a beer in hand for a few days, without having to deal with the complexity of another culture.

“One thing tour operators can do to help destinations is to help educate them about planning or being prepared and thinking through how they’re promoting themselves and who they’re promoting themselves to,” said Yves Marceau, vice president of buying and contracting for tour operator G Adventures. “It used to take years for a destination to become super popular. Now, with China on the move and with social media, a destination can go from unknown to top 10 list within two years. The reality is if the destination has limited capacity, it can be overrun very quickly. You look at place like Iceland and there’s more tourists than Icelanders. That happened very fast, and you see places where it is happening even faster.”

By limiting the numbers of licenses available to tour operators, or the the time of day they can operate in the most popular areas, destinations can limit the impact of overcrowding while providing a suitable experience for visitors. While tour operators often decide to stagger tour timings, regulations can help bring along those that don’t.

Expectations for access can also be set for tourists before they arrive, so they aren’t disappointed or disruptive upon arriving. Exclusivity, as we’ve seen time and again, is actually a major selling point for consumers.

Fueled by compelling global marketing campaigns and the frantic pace of social media, travelers now expect to tick a certain set of boxes while traveling. Destinations need to be aware that the image they present to travelers, and the demand created for access to certain experiences, simply can’t be provided sustainably.

4. Better Collaboration AMONG stakeholders

A rarely discussed problem is that local, state, and national tourism boards are generally tasked with promoting tourism and business travel instead of planning and managing it.

“The large majority of funds that go to any discussion of how to manage tourism go to marketing tourism,” said Epler Wood. “The rough estimate is maybe 80 percent of tax money that goes towards tourism in a destination generally goes to tourism marketing organizations, but they’re not management organizations, they’re marketing organizations. These people are starting to realize they could have a new role for what they do. What if you gave 80 percent of all the money to manage the destination? This was never a problem because we had a big globe and not many people traveling.”

Many destination marketing organizations have begun to reconsider how they can best serve the interests of locals instead of promoting rampant visitation growth. Executives on stage at the Skift Global Forum this year weighed in on their newfound approach to the problem, and this represents a good first step towards some sort of transition.

There is a deeper problem affecting destinations worldwide: There is no codified way to conclusively measure and quantify the impact that tourism has. While not impossible, it could be more fruitful for destinations to develop and test methods for solving overtourism by collaborating and trying to agree on a framework for finding solutions.

Several groups are working on this now, including Epler Wood’s colleagues, but cities and travel companies need to come to the table as well. In the long term, it’s not enough for destinations to just manage demand; they need to measure and manipulate the specific effects of overcrowding.

“We need to come to an understanding of how to measure those impacts and it’s not as simple as demand [alone]… people are trying to speak too generally about the problems and there’s a tendency to vilify certain parts of the industry,” said Epler Wood. “What I don’t think we can do is stop them from doing what they do. We need to do a good job measuring [the effects of tourism]. It’s well-known tourists want to go to specific places at certain times, so we have to think of other ways of managing their use [of destinations].”

Part of the problem, it seems, is having concrete details on where travelers go and how they affect the environment they are in, whether urban or remote. An international group of academics and tourism experts are working on a solution to this involving standardized monitoring methods in multiple cities worldwide.

Some places, like the Australian state of Tasmania, have experimented with offering travelers free smartphones that track their movements to provide more visibility to industry stakeholders on traveler behavior.

The more data and information cities have about the phenomenon and resulting disruption of overtourism, the better equipped they would be to act to prevent it by coming up with solutions based on evidence instead of conjecture or blacklash.

5. Protect Overcrowded Areas

It’s clear destinations haven’t done enough to prevent excessive tourism from hurting communities. The biggest problem is the speed at which tourism provokes change in a community. Cities want the increased economic activity from tourism, but are not well-equipped to make fast and responsive restrictions once unwanted changes begin to occur.

“It takes a lot of work and very quickly these smaller communities can be overrun, much quicker than a city like Barcelona,” said Marceau, of G Adventures. “Those are much more difficult things to fix. That’s a more difficult one because the effect of one company is not as impactful.”

Some cities like Barcelona have turned to legislation to curb the influx of tourists. Tour operators, as well, have shifted how they conduct tours, often staggering the times which certain groups arrive in order to reduce congestion.

As we’ve seen, however, tourism is often interlocked with overall economic development in cities.

“We should be really welcoming to tourists and, yes, it is disruptive,” said the European Tour Operators Association’s Jenkins. “You go to a city, and there’s lots you can’t have if someone wants to pay more for it. It’s totally normal for people to see areas you grew up in as a child become unaffordable as an adult; that’s because new people have arrived.

“In Barcelona, this is what happened. Tourism is economic activity which in broad terms has a very small environmental footprint and has a very massive economic impact. These are people who use existing means of transport and existing infrastructure and patronize preexisting forms of social enterprise.” There’s also the phenomenon of local business owners feeling resentment against businesses that find success catering solely to tourists, he said.

Marceau has noticed the phenomenon in destinations that have geared up for luxury tourism as well. He mentioned the development of Playa del Carmen into a series of luxury resorts as an example of how the benefits of even expensive tourism don’t necessarily reach nearby communities.

Perhaps large cities should take a page out of the playbook employed by smaller destinations such as the Galapagos Islands, Machu Picchu, and Palau that have had no choice but to limit tourism growth. Those have detailed and stringent forward-looking plans governing access to and the development of their attractions.

Why can’t cities develop similar strategies for coping with periods of the year when more tourists visit than its most popular areas can handle?

Breaking The Pattern

The reality is that the forces of global capital and travel have shaped the development of cities for centuries. Today, however, we are seeing more places built specifically for tourists.

“Even in places that have been built [specifically] for tourists, it’s interesting that tourists go to experience something that is not contemporary,” said Jenkins. “The result of this is places like Disney World or the hotels in Las Vegas. What normally happens is they start as tourism centers, then conference centers, then residential centers, and finally they don’t want tourists anymore.”

We’ve explored this tourism-driven gentrification before, and cities like these represent examples of locales that have embraced tourism and the transition towards an economy serving visitors and wealthy residents instead of the majority of locals.

Epler Wood’s recent book Sustainable Tourism on a Finite Planet: Environmental, Business and Policy Solutions is a thoughtful examination of the issues at play related to overtourism. She concludes that the first step toward a solution entails international collaboration among cities, governments, and companies.

“What most people have seen is that government and industry are not collaborating enough,” said Epler Wood. “They need to see the stakes are so high that joint solutions are necessary and have to be based on data, and not just industry data, because they set their own parameters…People, be they from the industry or a destination, don’t want too many people swamping what is a beautiful cultural or historic site.”

As the stakes become higher in cities around the world, it still remains unclear whether there is the will to push tourists — and their money — away.

The Daily Newsletter

Our daily coverage of the global travel industry. Written by editors and analysts from across Skift’s brands.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: barcelona, overtourism, tourism, venice

Photo credit: A cruise ship in Venice. Cities across Europe are struggling to cope with increased tourism. bass_nroll / Flickr