Skift Take

Is there a big enough market for travelers to track flights through push notifications and wait weeks or months to buy instead of going to a website and entering their itinerary details? Hopper, Hitlist, and others think Millennials and others will shop this way but there is skepticism about how large these businesses can become.

Consider the $61 million bet that investors have made this year in app-only flight-booker Hopper, a nine-year-old “startup” that appears to be finally finding its footing.

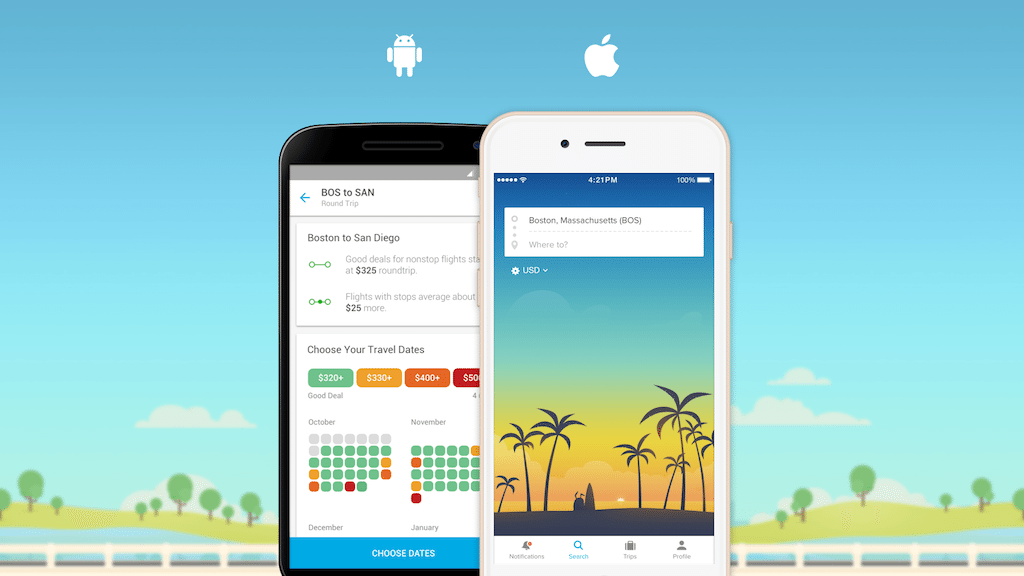

The iOS- and Android-only flight app, which counsels travelers to buy now or wait to purchase a ticket, markets itself in social media and messaging apps only, says founder and CEO Frederic Lalonde, charges booking fees when just about everyone else long ago abandoned them, and bases its strategy on the desktop and mobile Web being on their last legs five to 10 years from now.

On top of that, Hopper, like its smaller rival Hitlist, faces the uphill battle of trying to change consumer behavior and the traditional way travelers shop for flights. The premise is that they will be content to start searching for flights months or weeks in advance, and then wait for Hopper to surface the deals and keep updating them, alerting consumers through a stream of push notifications on their phones.

Hopper thus targets price-conscious flyers and not brand-loyal or business travelers who might ordinarily book on United.com or Delta.com to accrue rewards. Lalonde claims that more than half of Hoppers users are Millennials, and the company markets to them through social media and message apps. No Google Adwords or metasearch, he adds.

Conversational Commerce?

If all of these elements weren’t contrarian enough, Lalonde says Hopper is engaged in a form of “conversational commerce” as it “talks,” or interacts with users through push notifications, four times weekly on average to build “a deep trust” with “a flight ticket as a byproduct.”

Tying airlines, flights and trust into a single paragraph would give many people pause but Hopper aims to build such allegiance with its customers.

Welcome to Hopper and the nine-year-old company that is seemingly making strides after embarking on a path that had several zigs and zags.

The $61 million Series C round for Hopper, with offices in Montreal and Boston, includes new funding and a $12 million convertible note announced in March, that brings Hopper’s total funding to date to $78 million ($104 million in Canadian currency), the company says.

Caisse de depot et placement du Quebec (CDPQ), a pension fund manager, led the round, and drew participation from existing investors Brightspark Ventures, Accomplice, OMERS, Investissement Quebec and BDC Capital IT Venture Fund.

It has indeed been a long road for Hopper’s initial investors but consider some of the metrics that Hopper claims today: Lalonde says the company, which began taking flight bookings 14 months ago, generates about $1 million per day on average in gross bookings. The company states it has 10 million users who have tracked 18 million trips and that its growth has been “23X.”

Hopper states that its apps are being downloaded 35,000 times per day — and the company obviously is buying many of those downloads. It isn’t too difficult to buy downloads but a key question is whether Hopper is retaining these users in a meaningful way.

Lalonde doesn’t provide many specifics but says that about 80 percent of people who download Hopper’s apps give permission for push notifications so they may end up purchasing a ticket months after downloading the platform. In that way, he argues, the company doesn’t have to continuously reacquire travelers who downloaded the app and forgot about it.

Still a lot of consumers might use the app to track flights but then book them on an airline or online travel agency website. Lalonde counters that Hopper is building trust with users and that its conversion rates are “an order of magnitude greater than on OTAs.”

There’s No Money In Selling Flights?

So how does Hopper make money in an era when so many airlines eliminated commissions paid to travel agencies?

Lalonde said Hopper takes in revenue from its booking fees, which average around $5 per ticket, incentives paid by the global distribution systems it is connected to, and commissions from airlines, mostly outside the U.S. but a few domestic ones too.

Hopper doesn’t offer flights from Delta, Southwest, easyJet, or Ryanair.

Why would a consumer pay Hopper a booking fee when they can buy airline tickets elsewhere without paying them? Lalonde said Hopper is saving consumers considerably more money than the booking fees in the form of lower fares, including private fares that some airlines provide to the company because most push notifications are private and not available to the general public.

A Long Road

Founded in 2007, Hopper initially saw itself as building a database of flight and destination information and considered options as a consumer brand or a business to business offering. Now it is solidly a consumer app.

After building its technology for six years, Hopper tentatively unveiled its first product, an alpha version of a destination-oriented website that billed itself as “the world’s largest travel catalogue” in 2013. The product wasn’t pretty and was widely panned.

Lalonde says it took five years and $12 million to build its data platform and, regarding the initial consumer website, he says “we just built the wrong thing.”

It was then back to the drawing board and Hopper launched as a flight-tracking app early in 2015. Lalonde says “social has beaten AdWords” and the company can personalize offers through its social media marketing and push notifications.

One of the ways it earns loyalty and generates bookings is by offering travelers a deal on a flight to Milan when they initially signed up to track flights to Rome, Lalonde says.

Flight Predictions

Hopper’s database has collected and analyzed trillions of flight prices and it claims 95 percent accuracy when advising consumers to buy now or wait to book a ticket. Google Flights and Kayak likewise offer flight predictions as did Farecast, which was sold to Microsoft in 2008 and later shuttered.

The Wall Street Journal tested Hopper’s flight prediction prowess and found that it was accurate 8 out of 10 times.

Over at Hitlist, founder and CEO Gillian Morris welcomes the attention that Hopper is drawing about what she describes as “the alert space.”

“It’s the only rational way to go about booking flights,” Morris said. “I think it makes no sense that people do all the work themselves.”

Founded in 2013 and with about $1 million in funding, Hitlist, like Hopper, is trying to change consumer behavior in the way people book flights.

While Hopper doesn’t offer advertising and is becoming a flight booking app, Hitlist generates the majority of its revenue from content syndication and native advertising within its app, Morris says.

Still, there are a lot of skeptics about both Hopper, Hitlist and the push notification space in general for flights.

Can these companies really build trust and a sense of community? Is there enough money in the flight business, and how will they deal with people who use these apps to track flights and then do their e-commerce elsewhere?

The space is definitely drawing more interest and players, and that’s something the existing competitors welcome.

The Daily Newsletter

Our daily coverage of the global travel industry. Written by editors and analysts from across Skift’s brands.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: apps, flights, funding, hopper

Photo credit: Pictured are representations of Hopper's apps. Hopper enables consumers to track flights, and counsels them whether to wait or buy now for the best deal. Hopper