Skift Take

There are many travel brands that are seemingly in violation of the U.S. Federal Trade Commission's new native ad guidelines on how to disclose when social media influencers were paid. Consumers appreciate brands more when they're transparent and develop deeper connections with influencers when they know what they truly support and enjoy when they're not being paid.

All of that behind-the scenes and seldom-disclosed compensation that a slew of travel brands bestow upon social media influencers may soon have to come into the open.

A settlement last month between the U.S. Federal Trade Commission and Warner Bros. may foretell stricter enforcement of guidelines on the use of social media influencers and force companies to be more transparent.

The commission hasn’t brought any charges against a travel brand, nor did it fine Warner Bros. But the Federal Trade Commission called out Warner Bros. for “failing to adequately disclose that it paid online influencers thousands of dollars to post positive gameplay videos on YouTube and social media” for a marketing campaign for one of its video games.

Do social media influencers or celebrities really enjoy that hotel pool or in-flight snack like they say they do? Even if they do are brands paying them for an endorsement but being discreet about it?

Those questions prompted the FTC to release updated guidelines last December and begin cracking down on how brands should identify and disclose native advertisements to consumers considering the growing use of social media influencers.

For consumers feeling frustrated with brands for not knowing which of their celebrity or influencer-featured social media posts are paid ads and which are not, the U.S. government has come down on the side of disclosure — although enforcement has been lax to date.

Many travel brands feature influencers or celebrities on social media with thousands or millions of followers that align with their brands. However, in many of these circumstances influencers were paid for their endorsements or to speak positively about a hotel or destination on Instagram or Snapchat.

But few brands clearly label these posts as ads and many don’t make any disclosures that these people were paid for their posts. Of course, any social media post from a brand is by nature an advertisement of products, services and experiences. The Federal Trade Commission, though, is concerned with posts that brands pay someone for rather than brands using and sharing user-generated content.

An excerpt of the updated guidelines follows:

“Because ads can communicate information through a variety of means – text, images, sounds, etc. – the FTC will look to the overall context of the interaction, not just to elements of the ad in isolation. Put another way, both what the ad says and the format it uses to convey that information will be relevant. Any clarifying information necessary to prevent deception must be disclosed clearly and prominently to overcome any misleading impression.”

“A basic truth-in-advertising principle is that it’s deceptive to mislead consumers about the commercial nature of content. Advertisements or promotional messages are deceptive if they convey to consumers expressly or by implication that they’re independent, impartial, or from a source other than the sponsoring advertiser – in other words, that they’re something other than ads. Why would it be material to consumers to know the source of the information? Because knowing that something is an ad likely will affect whether consumers choose to interact with it and the weight or credibility consumers give the information it conveys.”

“…The more a native ad is similar in format and topic to content on the publisher’s site, the more likely that a disclosure will be necessary to prevent deception. Furthermore, because consumers can navigate to the advertising without first going to the publisher site, a disclosure just on the publisher’s site may not be sufficient. In that instance, disclosures are needed both on the publisher’s site and the click or tap-into page on which the complete ad appears, unless the click-into page is obviously an ad.”

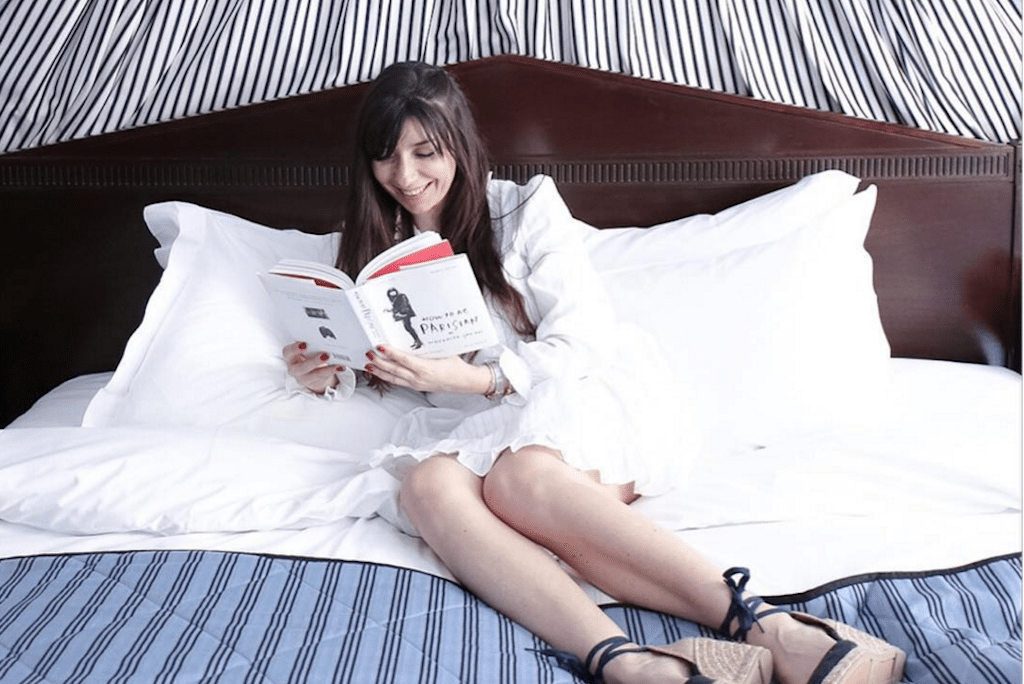

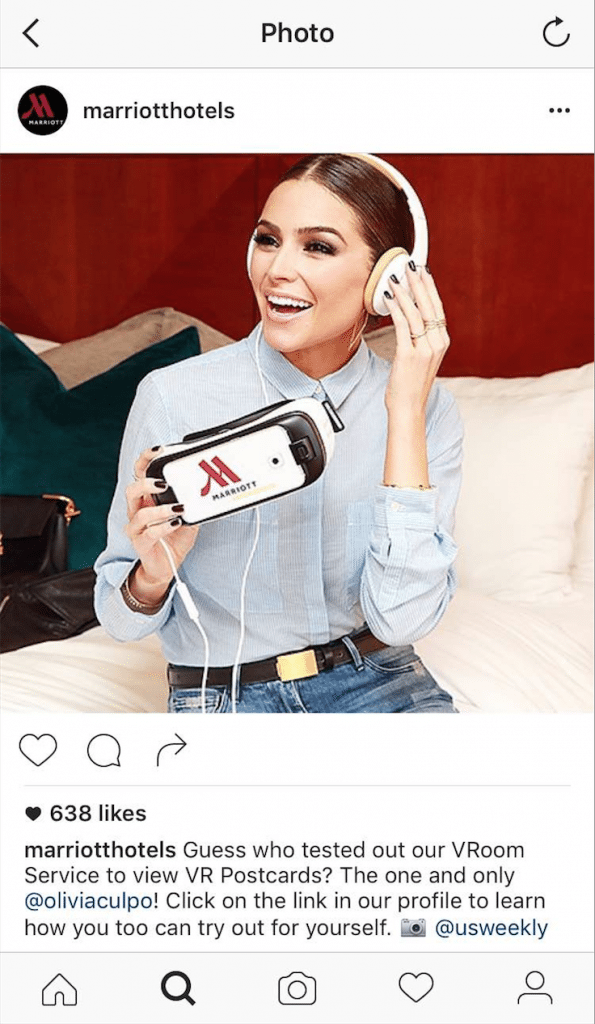

Below is one example of what the Federal Trade Commission may be referring to, although Marriott didn’t respond to a Skift request for comment. [Likewise, Starwood didn’t respond to a query about the fashion influencer, Marie Luv Pink, who appeared in the ad shown in the photo atop this story.] This post appeared on Marriott Hotels’ Instagram feed in September 2015 and features former Miss Universe and model Olivia Culpo, who has 1.3 million followers on Instagram alone, trying Marriott’s virtual reality headset.

It’s not clear if Culpo was paid for her appearance in the post (and there’s a chance she wasn’t) but it’s not far-fetched that she received some form of compensation. In fact, some influencers work virtually full-time in the role and receive ample compensation.

Complying With the Guidelines

Also at issue is influencers using their own Facebook or Instagram accounts, for example, to promote a brand without the influencer indicating whether they were paid. The Federal Trade Commission is concerned about transparency, said Enrique Dans, a professor of information systems at Madrid’s IE Business School, in a LinkedIn post, “given that brands are not explicitly named and effectively passing off advertisements as though they were simply messages.”

“The problem here is that a lot of brands are going about this the wrong way. Rather than trying to create relationships with people who might have some persuasive power in certain circles, many brands are simply applying brute metrics or using agencies whose interests are unclear, setting up tricky campaigns, often based on erroneous parameters.”

To comply with the guidelines brands must ensure their paid influencer posts identify the advertising:

- in clear and unambiguous language;

- as close as possible to the native ads to which they relate;

- in a font and color that’s easy to read;

- in a shade that stands out against the background;

- for video ads, on the screen long enough to be noticed, read, and understood.

Michael Ostheimer, a deputy in the Federal Trade Commission’s Ad Practices Division, told Bloomberg earlier this month that the commission doesn’t want consumers to mistake deception for endorsements. Using #ad or #sponsored, for example, might help some consumers understand an influencer was paid but doesn’t cover all the bases of the new guidelines, he said.

So far the Federal Trade Commission hasn’t brought any charges against a travel brand. But that could happen if travel companies and others aren’t more forthcoming.

Many influencers argue they genuinely like and support the brands that pay them to appear in posts and don’t view these situations as advertisements. Regardless whether that symmetry exists between influencers allegiances and brands’ marketing goals, the Federal Trade Commission now insists that brands identify the advertising relationship between brand and influencer.

The Daily Newsletter

Our daily coverage of the global travel industry. Written by editors and analysts from across Skift’s brands.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: ftc, influencer, marketing, social media

Photo credit: The Federal Trade Commission wants influencers, such as fashion influencer Marie Luv Pink, who was used by Starwood's Tribute Portfolio, to tell consumers when they've been paid by brands to post on social media. Marie Luv Pink / Instagram