Skift Take

By crushing passengers knees, airlines might just be shooting themselves in the foot.

The dogma of the aviation industry has been that the corporate buyer is the steadfast and profitable customer and aircraft interiors design has always been focused on attracting and retaining this customer.

Corporate customers fly out of necessity, paying whatever fare it takes to get to the next meeting. Also out of necessity, they will pay a premium to sit in a seat that keeps them productive.

By comparison, the Economy flyer has traditionally been a seat filler, a booster of load factors with corresponding cost efficiencies but not a reliable boost to revenue. This price-sensitive market is variable. Economy passenger numbers can be reduced whenever the economy takes a downturn.

These basic principles have long decided the product, marketing, and cabin design strategies of airlines, as they still do today. But changing passenger profiles, a changing global economy, and the hard-and-fast decisions airlines have made with their cabin product may have set in motion a dynamic with long-term negative repercussions for airlines.

Selling Pain

As industry analyst, Addison Schonland, Founder & Partner of AirInsight explains, by increasing the density of the Economy cabin, airlines “can boost capacity without adding to the fleet. Of course, as they shrink the coach section they force many to pay more to be able to have an ounce of comfort.”

This is a key element of the up-selling strategy employed by airlines today to boost revenues, shored up by unbundled pricing strategies which offer to sell the pain away. Features such as fees for seat selections, higher fares for exit row seating, and Economy Plus cabin offerings have become part of the new normal in airline product planning.

Analyst Robert W. Mann, Principal at R.W. Mann & Company, himself an industry veteran with direct experience developing airline products and strategies for American Airlines, Pan Am, U.S. Airways, and TWA, believes today’s Economy product has become punitive.

While Economy was never equal to the premium product, he confirms what many passengers say: that standards in Economy have now dipped too low for comfort.

“The legacy version of upsell was an acceptable level of service in Economy, to which you added desirable amenities in premium,” he says. “Now there seems to be a conscious diminution of space and services to push sales to the forward cabin. A large percentage of passengers simply can’t survive there. A 30-inch pitch is not tolerable for taller North American passengers. Basic Economy pitch won’t do for many, except for shuttles. It forces a survival-based purchase up, just to get that extra space. But if you have to get any work done, you can’t even use the laptop in Economy Plus. That forces you into domestic First class, if you’re a productivity buyer. You have to buy into the front cabin. That’s differentiation by punishment.”

As Mann sees it, traditional carriers are driving passengers to competition which may not provide a better product, but at least sets honestly low expectations.

“Airlines are not readying themselves for the pushback,” says Mann. “Corporate buyers get inducements to buy premium tickets. Elite frequent flyers have the options of upgrades, but airlines have misjudged the push back from the back of the plane. While economy passengers don’t represent the majority of revenue, they do represent the majority of customers. It supports the growth of ULCCs (Ultra Low-Cost Carriers).”

Out of Proportion

The unintended shoring up of low-fare competition results in a vicious cycle downwards, forcing those traditional airlines to match low-fares, even as loss-leaders. They also wreak havoc with cabin product configurations and proportional fares. When the baseline fare for the lowest product has a low price point, it affects the pricing dynamics in the forward cabin.

“Airlines must maintain a ratio of 6 or 7 to 1 against the lowest fares in Economy, to keep people from buying down,” says Mann. “There is a clear resistance to paying 8 to 10 times the Economy fare. There must be a measurable tangible service in both the hard and soft product, a differentiator which attracts passengers. Service is the determinant of perceived value, and the price points must have a correlation to that.”

In short, airlines have to find ways to make the higher fare justifiable. For luxury travelers, those affluent passengers who will buy the highest premium tickets out of pocket and fly at the highest fare tier more as a vanity purchase than anything else, the complete product must match high expectations. True First class products and services are expensive, while true luxury travelers may be affluent enough to fly private jets. On the whole, they are unreliable sources of income.

Check the Label

The bread and butter premium passenger is the executive corporate buyer, but post-crisis corporate policies have made buying a ticket labelled First class unacceptable. This has led airlines to reduce or eliminate First class product, replacing it with a product labelled Business class that still meets a high standard of comfort and luxury.

Premium, by any name, must meet a reasonable fare differential, as Mann states. The expense to develop premium products must be covered by seat a steady stream of customers, not lost to upgrades.

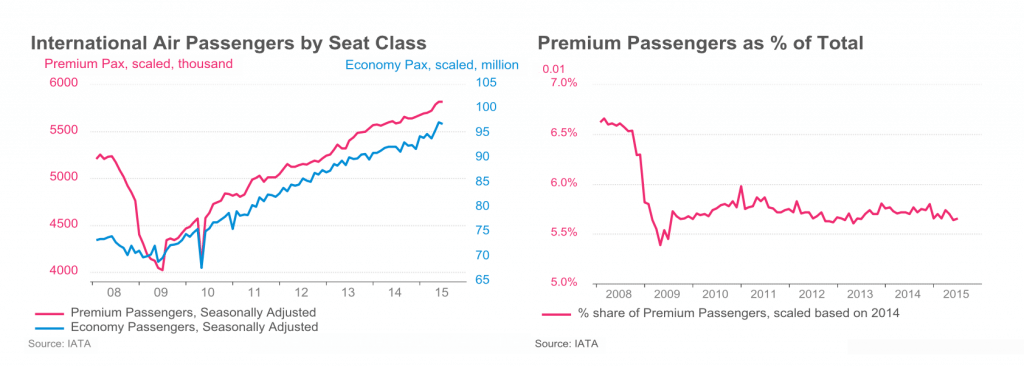

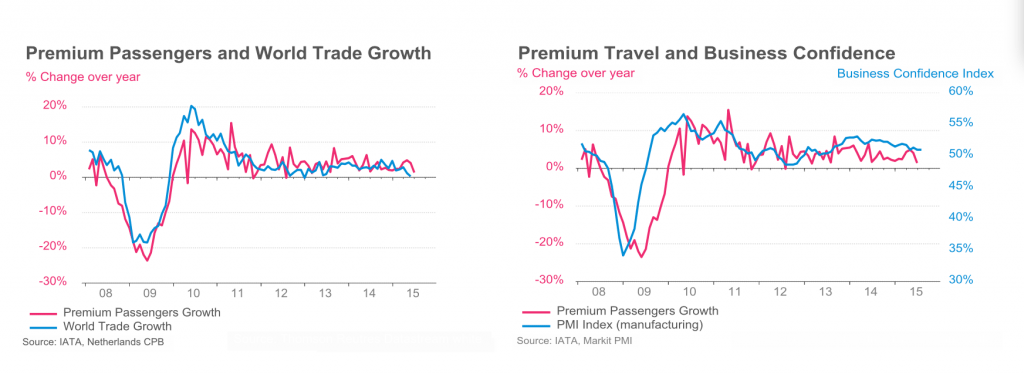

There are signs from The International Air Transport Association (IATA), that the premium stream could be slowly drying up.

“Growth in premium travel has been reflecting continued weakness in business travel demand drivers, with global business confidence being dragged down by emerging markets,” IATA states in its latest report on the sector.

IATA’s report validates Mann’s view that economy passenger numbers are only boosted by low-fare competition with Ultra-Low Cost carriers. “Growth in economy class travel—the more price sensitive travel market—has been supported by lower fares over recent months,” the report states.

IATA attributes lower fares to the fall in oil prices, something airlines could reverse if they needed to, but attributes the decrease in premium ticket sales to factors airlines do not control. “Premium passenger numbers have been growing but at a relatively slower pace due to overall weakness in business travel demand drivers.” Those travel demand drivers are world trade and business confidence.

A New Breed of Business

Some industry experts point out that the rise of an entrepreneurial class, the freelance economy, has created a new breed of business traveller who could fill premium seats, if the product were attractively packaged.

Because this traveller lacks a generous expense account, a fare differential of seven times the cost of an economy seat is a non-starter. Finding no adequate middle-ground, that passenger will endure punishment at the back, along with the variable economy leisure traveller.

If that is the growing class of worker for this new millennium, the aviation industry, stuck in its 20th century mindset, is building resentment in tomorrow’s core business customer.

Demanding Circumstances

“Economy demand can match price points if energy prices go back up, but we’ll face a reduction in frequencies,” says Mann. “It becomes a sunken effort. Airlines have invested a lot in Basic Economy. There’s risk attached to making experience in the back so bad that it limits demand.”

That demand will be limited is arguable, given the spike in passenger numbers IATA expects in coming decades. But those growth projections are based on sound economies, especially in Asia, something present reversals in the market would call into question. Regardless, if the economy downturns with those who can opting out of travel plans, corporate policies tightening again, and the remaining gap to be filled by disgruntled entrepreneurs trained for pain, perceiving little difference between flying flagship or flying budget, the repercussions could be lasting.

Schonland sees an additional problem in the works for airlines: just keeping up with growth. He attributes recent reduced frequencies and shifts to larger aircraft to a shortage of qualified pilots. “Using bigger planes means making money from the same crew cost knowing they will go from less than 85% load factor to approximately 90% on a bigger plane. So we are seeing fewer flights with bigger planes moving the same number of people at similar cost.” These staff-driven fleet decisions are themselves difficult to reverse. The Air Line Pilots Association ALPA, which argues against the concept of a pilot shortage, suggests the pressure to compete with low-cost carriers has led to starting wages that make the pilot career path unattractive.

In fairness to airlines, the industry has never been a profitable one. Even with today’s best performance, airlines are far from reaching financial numbers that would impress the markets. That too is part of the problem. Wall Street seems to hate it when airlines make passengers happy.

“In a choice between caring about the customer and caring about shareholders, the customer loses every time,” says Schonland. That’s just how it goes. Which is why you see such a vitriolic reaction to the success of the ME3 (Gulf Carriers). These new airlines focus on the customer and it shows. The US carriers hate the idea of these carriers growing their footprint in the U.S..”

Despite a highly differentiated product and luxury comforts unimaginable on other airlines, the Gulf Carriers are not immune to the pressures of filling seats. Etihad just announced an unbundled fare structure. Emirates announced earlier this year that it wants to switch to a two-class A380 with higher density, in key European markets where flying First class would be frowned upon, and Qatar Airways, while keeping some room for first in its A380, has focused on its Business class product, allocating a significant cabin footprint to rows of nested Business class flat-bed seats.

No Going Back

Changing cabin configurations and updating cabin product cannot happen fast enough to deal with sudden shifts in the passenger mix, and that has always been the challenge for airlines. Once resources are committed to a cabin lay-out. Be they full or empty, those cabins fly. The average life of a cabin configuration is ten years. Planning for new interiors programs can require up to five years lead-time.

Mann believes that traditional airlines may already have done irreversible damage to brand positioning by offering by competing down on fares, increasing cabin density, and matching a ULCC unbundled product sales strategy.

“The die is cast and it’s gone,” he says. “The Ultra-Low-Cost model isn’t going away. The low cost carriers are the ones to watch. They would see the turn in the market sooner than anyone, and it’s clear the market has turned.”

The Daily Newsletter

Our daily coverage of the global travel industry. Written by editors and analysts from across Skift’s brands.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: airlines, inflight, low-cost carriers

Photo credit: An 11-across configuration on an Airbus plane. Airbus