Luxury Ski Spot Breckenridge Tries to Diversify Its Seasonal Economy

Skift Take

Breckenridge is the quintessential mountain town known for its picturesque village, ski slopes, and the wealthy clientele it, alongside Vail and Aspen, attract all winter long.

But like many seasonal destinations, Breckinridge’s business drops significantly when its affluent visitors head for more traditional warm-weather destinations.

Occupancy rates in the winter were consistently 20- to 30-percent higher in the winter than the summer over the 12-year period between 2006 and 2017.

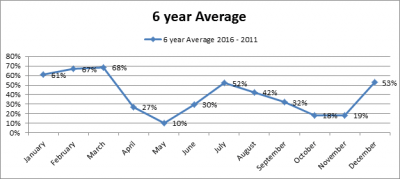

A month-by-month breakdown shows that while winter clearly boasts the highest occupancy average peaking at 68 percent in March, summer is also a popular time with occupancy rates reaching 52 percent in July.

Numbers are based on a six year average between 2011 and 2016.

The destination’s challenge periods are during spring and fall when average occupancy rates can fall to as low as 10 percent in June. This is what locals call mud season as rain turns otherwise ski slopes and hiking trails into mud.

Introducing creative food was one step to diversifying its appeal. For example, vegan pizzeria Piante Pizzeria boasting New York-trained chef Jason Goldstein opened last year. And local favorite South Ridge Seafood Grill added vegetarian and vegan options to its menu after moving to a new space on the main street.

However, a slow movement to attract the remote workforce, location independent creatives and businessmen with successful are now starting to bolster the town’s population during fall and spring.

“We’ve always seen seeing an influx of new seasonal residents at the start of the winter season, but in the past few years, the seasonal workers are moving to Breckenridge and Summit County and not seeking jobs. They’re coming, instead, with full-time, good-paying, professional jobs,” explains Amy Kemp, founder of local co-working space Elevate and a major advocate for branding Breckenridge as an outpost for remote workers.

“This is a huge shift and transformation for Breckenridge and other mountain towns. Many of them are choosing to stay beyond the ski/snowboard season.”

In addition to two co-working spaces Kemp organizes Camp 9600, a creative “unconference” that just wrapped its third year. Held in September, the event draws attendees from major outdoor and travel brands and publications.

“A big part of the success is because we schedule time for mountain biking, hiking and yoga and host many of the sessions at local bars and restaurants and coffee shops – so they’re able to experience Breckenridge versus sitting in a convention center all day in the middle of one of the most beautiful mountain towns.”

There are no statistics available that capture the increasing number of remote workers and freelancers choosing to move to Breckenridge and mountain towns, but Kemp says they are working with state demographers and local governments to try and better qualify the growth.

One can’t talk about a growing population of come-and-go residents without broaching the topic of Airbnb and the sharing economy.

Outside Magazine published a piece this summer looking at the impact short-term rentals had on Crested Butte, located three hours from Breckenridge, which spread quickly among the mountain towns. It has impacted workforce housing in each destination while also bringing a new livelihood for other residents.

“Mountain town folk have always been pioneers. They were the prospectors, the early adopters, the dreamers who risked everything and came west for new opportunities. Today, it’s no different. We’re still pioneers and for those locals who are willing to dig deep, work hard and dream big, technology and entrepreneurship will usher in a new ‘gold’ rush,” Kemp argues.

“Of course, there’s the risk of the boom and bust cycle of any ‘gold rush’ or tourism economy. So, the key is to diversify our economy. And, to create a year-round, healthy economy that can support locals.”