Skift Take

Brands have overtaken independents in the U.S., and that trend looks set to repeat itself abroad. But independents have held up better than expected in the past year. Perhaps the U.S. market is reaching an equilibrium.

Some industry observers speculated that the pandemic would speed up consolidation of the hotel sector, as owners of independent hotels might find cost and other pressures too difficult and would essentially sell out to the big brands. So what was the state of the independent hotel sector in 2022, as the pandemic subsided, according to just-released numbers?

In recent years, only about one-third of the roughly 60,000 hotels in the U.S. have remained independent, making the country arguably the world’s most consolidated hotel market.

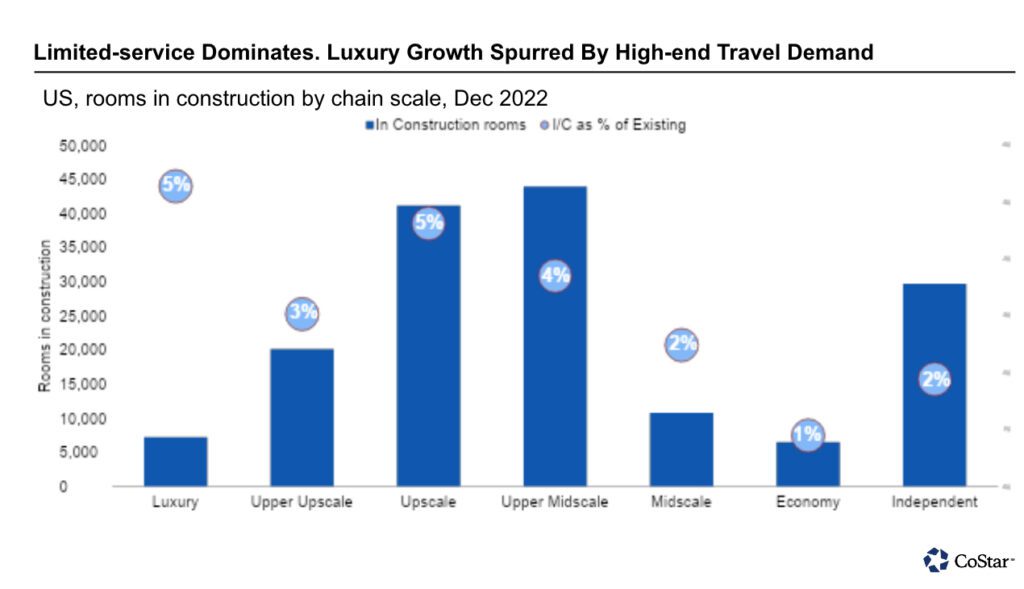

The gap between independents and brands truly yawns when you look at the hotel development pipeline. As of late December, unaffiliated hotels representing approximately 30,000 rooms were in construction — a growth of about 2 percent, according to STR, the gold standard for hotel performance benchmarking. Yet branded and franchise hotels had a whopping 131,000 rooms under construction.

“We are becoming a country of brands,” said Jan Freitag, national director of hospitality analytics at CoStar Group. “It’s what the banks like, it’s what the owners like, and it’s what the customers want.”

The trend isn’t only a U.S. phenomenon. In Britain and Ireland, the independent hotel sector contracted around 12 percent between 2010 and 2019, according to estimates by Whitbread, the parent company of budget lodging brand Premier Inn. Rising bills for energy and workers’ wages may prompt many independent hoteliers to exit the sector and enable Premier Inn to take share, the company forecasts.

While independent hotels have faced long-term challenges, the pandemic didn’t necessarily hasten the “brandification” of American hotels.

In 2022, growth in the segment of hotels not affiliated with a brand or franchise was anemic, but there wasn’t a decline, per se. In the U.S., at the end of 2022, STR said there were 25,544 independent properties representing 1,511,716 rooms. Compare that with 2019, when there were 25,839 independent properties with 1,531,627 rooms.

Those numbers are net totals. In 2022, for example, 359 independent properties, representing 24,488 rooms, closed, STR reported. But more than that opened, making up for the loss.

Independents did struggle a bit more than hotels that were flagged. Last year, 214 branded and franchise hotels representing 21,070 rooms, closed. Given that there’s a bigger pool of branded hotels than independents, that means independents had a higher percentage closure rate than branded properties.

As context, the long-run average for U.S. permanent hotel closures in the decade before the pandemic was 29,000 rooms a year. That shot up to over 60,000 in 2020, about 35,000 in 2021, and about 45,000 last year. The pandemic did lead to a shaking out of the U.S. hotel sector, but independent hotels weren’t disproportionately affected in absolute numbers.

“It’s long Covid for the hotel sector,” Freitag said. “It was two years of a tough slog, and now you have refinancing woes in a rising interest-rate environment. Some owners may think it’s no longer worth it.”

The brandification of America is an ongoing trend for a few reasons.

“Having a big loyalty program matters tremendously,” Freitag said, noting that millions of consumers find the rewards programs highly motivating as a game to play.

Distribution costs are another factor.

“From an owner’s perspective, if you’re truly independent, you’re putting all your money in Google’s basket, basically,” Freitag said. “You have to drive people to your website, which, I’m not disagreeing, can work for some properties in specific locations — but that’s a tough battle.”

Joining a soft-branded collection is one of the middle paths owners take. Rather than own a purely independent hotel, owners sign up their property to “a collection.” Choice Hotels invented this practice in 2008 with its Ascend Collection, now the largest soft brand, with more than 300 properties. Hilton has collections called Curio and Tapestry. Accor has Emblems, MGallery, and Handwritten. Marriott has Autograph and Tribute. And so on.

“Coming out of the pandemic, we’ve seen that a lot of independent boutique hotel owners are longing for support from big groups such as Accor in reaching customers around the world without losing their identity and personality and characteristics that they have put in their blood, sweat, and tears over many years to achieve,” said Alex Schellenberger, Accor’s chief brand officer.

Soft brands are for owners who want to retain control of their distinctive properties while still benefiting from a big brand’s giant loyalty program and distribution engine. They come with fewer rules, or standards, to follow. Plus, their fees may not be as high as with a traditional hard brand in a comparable category.

There’s a case to be made that U.S. hotel brandification has gone about as far as it can go. If you own a property in a desirable location, you’ve either flagged or decided to stay independent. You’ve survived the pandemic, a worst-case scenario, and the trauma forced you to rethink operations in ways that may make you more efficient. New trends in cloud-based technology and social-media-based advertising may have somewhat leveled the playing field for some types of properties competing against the big brands. Perhaps most of the future attrition will come from older properties fading out of the system.

“Owners of properties that might be, say, 60 years old with an outdated design like exterior corridors, might decide the highest and best use of a property commercially is as something else, like an Amazon warehouse,” Freitag said.

What’s more, the secular trend should force a strategic rethink by the larger brand companies. The prospect of a smaller market means the brands need to find ways to become more cost-efficient and fight more intensively for share. That may lead to mergers.

More likely, it will lead to ambitious foreign expansion. In Europe and much of the world, most properties remain independent. The brandification of the world is still in its early stages.

CORRECTION: This story originally said there were roughly 160,000 hotels in the U.S., and I regret the error.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: branding, brands, future of lodging, hotel brands, independent hotels

Photo credit: A common area at the Bluebird by Lark hotel in Lake Placid that opened this month. Photo by Matt Kisaday. Source: Lark Hospitality.