Skift Take

Airlines need to shift from forecasting models that rely primarily on historical data to ones that analyze real-time demand. That's how Amazon and other e-commerce companies handle pricing. No wonder travel tech players PROS, Amadeus, Sabre, and Flyr spy an opportunity.

The pandemic caused a plunge in demand that has stumped the software that airlines use for pricing. The airlines have been responding by changing how they forecast demand. The changes are shaking up revenue management, a specialty that airlines have spent hundreds of millions of dollars on in the past decade.

While demand has plunged more than 70 percent on many routes, airlines have tried to keep their pricing power. United cut its domestic U.S. one-way ticket prices only 10 percent year-over-year to $228, including taxes and fees, during the second quarter, according to most recent data yet released by the U.S. Department of Transportation and analyzed by travel data company Cirium. Frontier trimmed fares only 8 percent on average, to $68. Delta trimmed 14 percent to $208, on average.

As airlines rethink their fares, loosening rules, trying continuous pricing, and adopting artificial intelligence techniques are on the agenda. One common goal is to simplify what their customers see.

“We’re making the airline easy to do business with,” said Vasu Raja, the chief revenue officer of American Airlines, during the a Bernstein investor’s conference in October. “That sounds like a strange thing for those who’ve been around the world of airline revenue management for a long time because probably in no company has there been such, in some cases, byzantine pricing and customer policies.”

Many airlines dropped or loosened up restrictions on change fees and refunds. More changes are likely.

“In a world where there’s simply not enough customers or demand, which by the way, is a problem that the airlines have never had to do any other crisis, it’s imperative that we are easy to do business with,” Raja said. “So many of the things that we’ve clung to, like a historically driven yield management forecast, or certain attributes of the network that impact competitive pricing, are really going to start to change.”

Simplification refers to what customers see, not the pricing process. The complexity of these calculations are mind-boggling, as a scan of patents for revenue management techniques filed by travel tech giant Amadeus and the revenue management team at American Airlines in the past few months reveal.

Until the crisis, the revenue management software was a reliable guide for airlines.

“Demand is pretty predictable in normal times,” said Justin Jander, director of product management at PROS (Pricing and Revenue Optimization Solutions). “As an individual flyer, you probably think your behavior isn’t predictable. But generally speaking, when you’re flying millions of passengers per year, you can really get a pretty good feel for demand.”

Yet the pandemic skewed the typical patterns of peak and low seasons — and the patterns of boom and bust economies, too.

“There’s a lot of talk now about throwing away all your historical data,” Jander said. “But even though demand is way down, there are still signals that are useful from what happened in the past, such as the seasonal shape of demand and how weekdays tend to differ from weekends. So the real challenge is to add newly relevant signals and blend them in.”

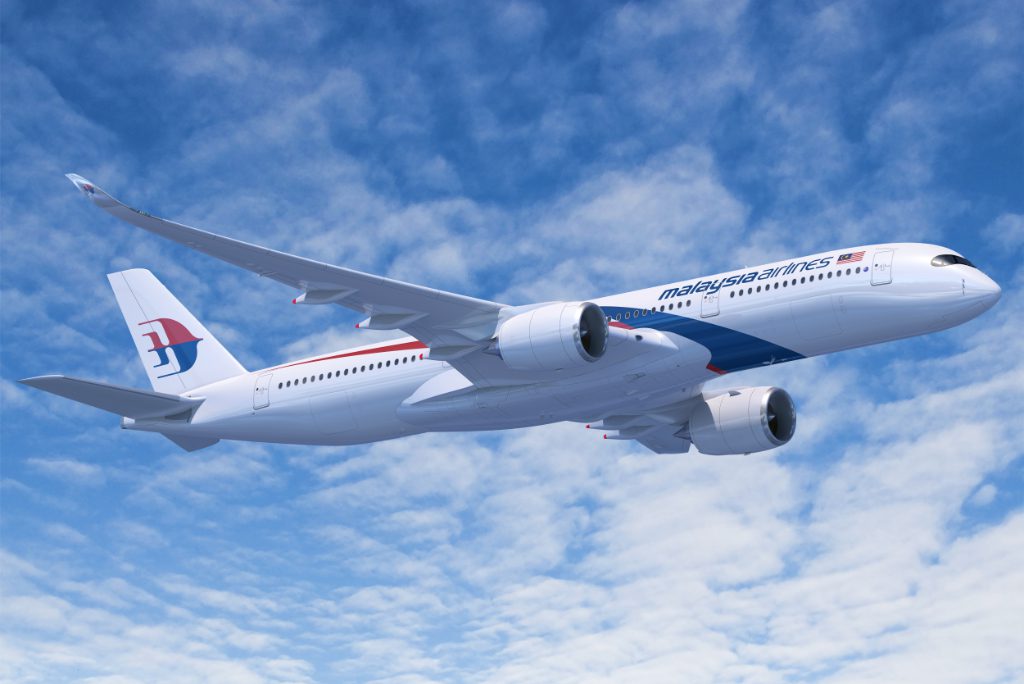

PROS, a public company based in Houston, has helped airlines with revenue management since its founding in 1985. It has since diversified its client base, but approximately 40 percent of its revenue comes from selling revenue management services to airlines. It has a significant share of carriers flying international routes, like Malaysia Airlines.

Earlier this year, PROS set up a task force with 17 customer airlines. It got anonymized bookings data from the airlines and paired data with external sources to figure out which signals today are best at predicting booking trends. For example, if there is a reduction in infection rates at a destination, how far behind do bookings lag — and for which departure dates? By pooling data, the task force was able to draw conclusions that were more precise and reliable. PROS has been updating its models to account for the telltale signals, such as infection rates.

The relevant signals may change as the pandemic unfolds. Vaccinations may have an unintentional social side effect of creating more public conflicts, according to Stat. That might protract the public health crisis in many countries, leading to an uneven or erratic recovery in flight demand.

Inspired by Amazon’s Pricing

The pandemic forced airlines to loosen their grips on their traditional ways of pricing tickets. That’s opened a chance for them to borrow techniques polished in the retail sector.

E-commerce companies tend to set prices by heavily weighting how customers have been shopping and buying in recent days, rather than look at data from years past. Airline tech providers have used 2020 to tweak their approach to more closely mimic that logic.

“Airlines need a forecast that can capture the most up-to-date demand patterns based on as little as a few months’ worth of live sales data,” noted Thomas Fiig, director and chief scientist, airlines research and development at Amadeus, in a blog post this year. “To overcome this challenge, our revenue management research team have developed a novel demand forecast that we call Active Forecast Adjustment (AFA), which can quickly adapt to changes in market demand.”

Alaska Airlines went live in September with the revenue management system that takes advantage of this Amadeus tech.

Testing Continuous Pricing

Since October, several airlines and tech companies have been experimenting with continuous pricing, another new innovation.

Continuous pricing aims to dynamically adjust fares in response to “real-time” demand signals. It aims to overcome the typical lag that happens when relying on historical trends and rough rules of thumb.

“Typically, there were two fares filed in the marketplace, and you could either charge, say, $100 or $200,” said Jander of PROS. “Well, what if there was enough information to tell you that you should charge $150 based on traveler search signals? That’s where our dynamic pricing methodology allows you to be a little more aggressive and roll out prices that aren’t those fixed static price points.”

Some backstory, first. Most airlines have a pricing team and a so-called revenue management team.

The “pricers” decide what fares make sense for particular products without necessarily analyzing demand. For example, if a plane ticket is restricted and only available for sale two weeks before departure, the pricing team may give it a different fare than they would for a last-minute ticket.

The pricing teams have tended to set fares in 26 stair-step levels. Each booking class has a band of fares. When seats sell out in one class, computers promote seats in a costlier one.

Revenue managers tackle other parts of the puzzle. They forecast how many of each type of passenger will care about each product, such as how many people will be buying two weeks out from departure.

Next, revenue management software will suggest what fares to put out to the market, based on the pricing team’s forecast and some estimates of those travelers’ value, or propensity to spend. Revenue managers then use their expertise to tweak the system’s recommendations. If a revenue manager knows a significant sports event might drive unusual demand at a particular destination on a specific day, they may push the fare up.

Continuous pricing takes a more dynamic approach by having fares fluctuate based on demand signals in the market, such as a surge in online searches for a particular route.

Lufthansa Group on October 20 began to offer “continuous pricing” through its direct connections, starting with most fares in Europe. British Airways also recently began experimenting with offering continuous pricing via some agencies.

Experts expect many larger airlines to take inspiration from the organizational model of most low-cost carriers by blending their pricing and revenue management departments. The goal is more coordination between pricing and demand forecasting teams.

Flying Blind When It Comes to Pricing

PROS competes with others in providing revenue management solutions. Sabre and Amadeus are other major players. Some other companies that sell either revenue management or related tools include Accelya (owned by Warburg Pincus) and Infare, a 20-year old Danish company that provides airfare benchmarking data.

A newcomer to the sector is Flyr. The startup launched in 2013 as a consumer service to forecast the price of airline tickets. But it pivoted three years ago, thanks to an insight it got from mentors and investors at JetBlue Technology Ventures.

Flyr now sells Cirrus, a “revenue operating system” that the company says stands out in how it uses contextual information to inform pricing decisions by applying concepts in artificial intelligence and machine learning.

“We use a technology called embeddings, which you will find in natural language processing, where the sequence of words in a sentence tells you a lot about its meaning and helps you to translate it,” said co-founder and president Alex Mans.

“We have built a similar thing for airlines,” Mans said. “We can understand patterns on routes, origins, destinations, departure times, competitive profiles, and how they relate to each other, using a neural network across the airline. This insight allows us to extract signals from the network where it is relevant and apply it to a single flight or a single market, even if you don’t have an explicit signal on that flight or that market in the form of bookings or demand.”

“So where a legacy system might be flatlining its pricing strategy because it has no signal or new information, we can change that pricing more effectively because we can transfer knowledge across the network to specific flights,” Mans said.

Similar innovations are percolating in the market.

Travel tech giant Sabre alternatively offers Revenue Optimizer, which promises to enable an airline to take “a 360-degree approach” to forecasting and analyzing revenue streams. The solution promises to show a current view into the total revenue potential of each flight by forecasting all relevant revenue streams, including ancillaries and codeshare flights.

In November, GOL, Brazil’s largest domestic airline, finished its migration to Sabre’s Revenue Optimizer solution.

As airlines rethink their approach to pricing, they may find themselves soon rethinking their organizations, too.

The software isn’t likely to replace revenue managers, experts said. But the tech may shift where revenue managers focus their attentions. Next-generation tools may direct analysts to focus on the flights and markets for which the expected revenue at departure is rapidly declining so they can manually fine-tune their tactics. The tool will let revenue managers prioritize markets where the most dollars are up for grabs versus competitor airlines.

That work will be critical as airlines try to push fares back up from recent lows.

The shift in job focus means that revenue managers could, over time, more actively work with network planning analysts to decide which routes should get which types of planes and how frequently a carrier serves those routes. To get to that point, airlines will have to break down traditional departmental, data, systems, and process silos.

The long-term impact of the pandemic could upend the very operational core of airlines forever.

The Daily Newsletter

Our daily coverage of the global travel industry. Written by editors and analysts from across Skift’s brands.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: amadeus, demand, dynamic pricing, flyr, forecast, pricing, revenue management, sabre

Photo credit: A Malaysia Airlines Airbus A350-900. The carrier is a customer of PROS, a revenue management solutions provider. Malaysia Airlines