Airbnb Well-Positioned Versus Peers Despite Pandemic Setback, IPO Filing Reveals

Skift Take

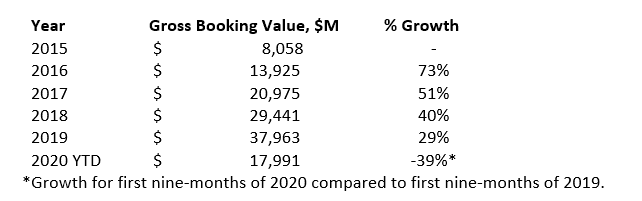

Airbnb was one of the fastest growing travel companies in the world before the pandemic hit. It grew gross bookings at an average annualized rate of 36 percent per year over five years. It hit $38 billion of bookings by 2019, up from $8B in 2015. Earning a commission of just under 13 percent, this translated to an impressive take of $4.8 billion in revenue for Airbnb in 2019, according to paperwork filed Monday for Airbnb's IPO, one of the most anticipated public offerings of the year.

But then Covid-19 hit. And Airbnb’s lofty growth was knocked off course. Year-to-date, the company has sold just under $18 billion of gross bookings. That’s down 39 percent from the same time period in 2019 and puts the company on track for a lower level of bookings than it saw in 2018.

Despite challenges posed by the pandemic, Airbnb did manage to post an operating profit of $418 million in the third quarter of 2020. This was partly achieved by a rapidly cutting costs, most notably turning off effectively all marketing spend and laying off 25% of its workforce.

Profits were also aided by a sharp rebound in revenue during peak summer vacation season as Americans experimented with restarting domestic travel, but with a twist. Rather than use a hotel, many preferred to stay in short-term rental where they could stay longer, fit more people, and have more control over their living environment. Revenues quadrupled sequentially, hitting $1.3B in 3Q, from $334M in 2Q.

The caveat is Airbnb's extreme seasonality. It regularly earns the majority, or even all, of its annual profits from the third quarter. So even with the swing to a 3Q profit, the company may still see its fourth quarter and full year numbers end up in the red.

Airbnb's Market Position and Cash Flows Give Advantage Over Peers

Beneath the hood though, there is reason for Airbnb to be optimistic. It is well-positioned in the short-term rental space which has been the least bad segment in all of travel. In September, for instance, Airbnb saw its gross bookings decline by 17 percent compared to last year. Let’s put that in context though, in the third quarter of 2020, Expedia Group saw gross bookings fall 68 percent year-on-year, Booking Holdings posted a 48 percent drop.

There is also the fact that Airbnb has demonstrated an impressive ability to generate positive free cash flow, earning $520 million of free cash flow between 2011 and 2019. That makes Airbnb stand out as one of the most impressive tech platforms to come out of its cohort of unicorn startups.

Tough Competition looms as airbnb leaves the startup world

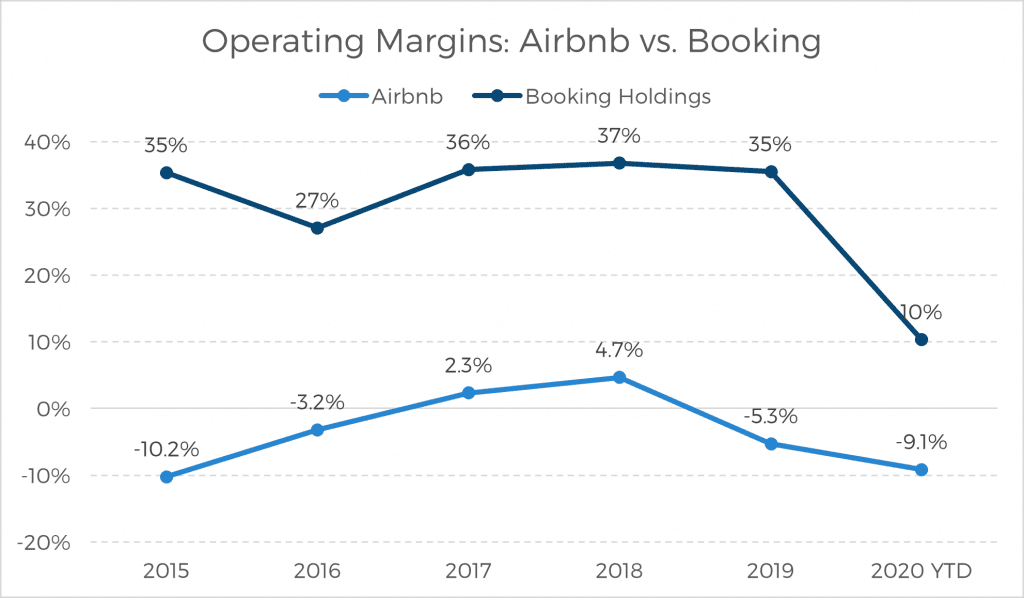

Much has been made of Airbnb's profitability. Many observers where shocked when Airbnb claimed an operating profit for the full year 2017 and 2018. This is because the company was being compared to other private unicorns with billion-plus valuations. This put Airbnb in the same league as infamous money-losing WeWork. In 2018, for instance, Uber reported 70 percent higher gross bookings but still managed to post a $2.8 billion loss compared to Airbnb's $171 million gain.

By these standards Airbnb is a super star. However, now as the company steps out into the world of public travel companies, it's relative performance may not look as strong. Airbnb has never achieved an operating margin greater than 5 percent of revenue. That's OK for an asset-heavy business, but asset-light online travel platforms are expected to earn far more. Booking Holding's by comparison consistently generates operating margins in the 35 percent range.

This is fodder for both the bulls and the bears. On the one hand it speaks to the huge potential Airbnb holds — can you imagine if it consistently earned a 20 percent-plus margin. But it also shows that the company is still young and has many growth and cost challenges ahead.

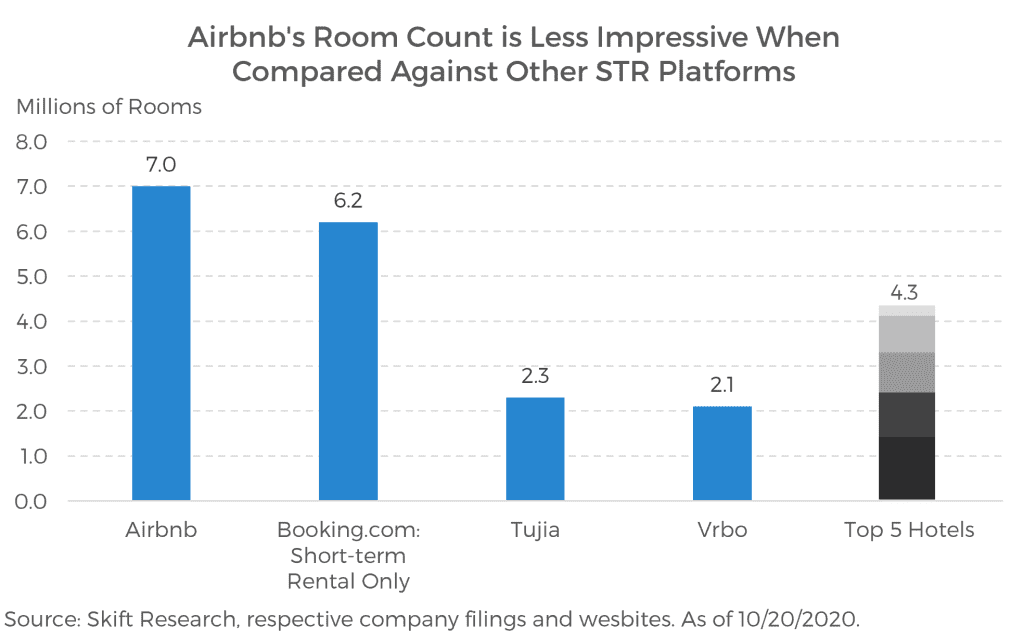

Booking Holdings, which has been working hard to integrate short-term rental listings onto its platform is also much closer to Airbnb in inventory terms than many realize. Yes, Airbnb’s is the largest platform in the space but Booking.com is not far behind with 6.2 million alternative listings in short-term rentals alone.

The bottom line is that CEO and founder Brian Chesky, has steered his ship well so far, but his greatest challenges may still lie ahead.

(This is story is breaking. Please check back for updates.)

From Air Mattresses to Quasi-Hotels

Chesky, Joe Gebbia and Nate Blecharczyk founded the company a dozen years ago in San Francisco as AirBed and Breakfast when they offered air mattresses for a fee in Chesky and Gebbia's apartment to attendees of a design conference to make their rent. Airbnb took an existing practice — renting second homes to travelers — revolutionized the model, and turned "getting an Airbnb" into a phrase that's a near-synonym for the entire category, at least in the West.

The trio no longer have trouble paying rent as the short-term rental giant and so-called unicorn, with a presence in more than 220 nations and regions, and boasting more than 7 million listings, built a globally recognized brand with a $31 billion private valuation before Covid-19 gut-punched Airbnb, the rest of the travel industry, and planet earth.

Airbnb didn't invent sharing homes. After all, HomeAway started taking vacation rental bookings in 2004, four years earlier than Airbnb, and the practice has been around for a couple of hundred years in one form or another. But Airbnb took the concept mainstream that an apartment owner or dweller could rent a spare room to a vacationing student or family, and there would be a level of trust between them to ensure a safe transaction and visit, all booked through a two-sided online marketplace that brought together potential guests with hosts.

There's no need to document here anew that there have been sporadic breaches of trust — witness Airbnb's press offensive all year to show it is clamping down on wayward house parties — and regulatory crackdowns around the world to ensure that apartment buildings and neighborhoods aren't getting short shrift.

Ripple Effect

Airbnb helped transform the hotel industry, with chains such as Marriott, Accor and Hyatt, launching or later abandoning their own homesharing answers to Airbnb, tweaking their designs, and trying to ensure that Airbnb doesn't encroach on their turf, which it has done to varying degrees. Online travel agencies from Booking.com to Trip.com Group and Expedia, which acquired HomeAway in 2015 for $3.9 billion, have ramped up their own portfolios of vacation rentals or apartments to offer leisure and business travelers the variety of accommodations' choice they're seeking depending on the occasion.

In its early days, part of Airbnb's brand-building was that it could offer travelers the chance to experience a vacation or business trip through the eyes of locals. Hosts, who might have owned an apartment or home or two, would often hang out with guests in the kitchen or on the backyard patio, and show them the tucked away restaurant down the cobblestone alleyway that wasn't listed in "Europe on $25 A Day."

Traveling Like a Local?

But over the years, Airbnb has lost some of that one-on-one charm, and that will be one of its ongoing challenges. There has been an increased corporatization of Airbnb with the advent of superhosts who own 100 rentals and operate quasi hotels, and venture capital-funded startups and arbitrage-minded speculators who view hosting and ownership as a real estate play.

"Small property managers (between 2 and 20 listings) comprise the largest portion of Airbnb supply, but larger property managers are also growing fast," according to a Transparent report last week. "Those professionals hosting over 100 listings have grown in number the most considerably."

Many of the mom-and-pop hosts around the world that still use the Airbnb platform cringe at the way professional hosts and large property managers seem to soar in Airbnb's display algorithms.

Airbnb provided its own tally about individual hosts versus professional ones in the S-1 statement. "As of December 31, 2019, 90% of our hosts were individual hosts, and 79% of those hosts had just a single listing. Additionally, as of December 31, 2019, 72% of our nights booked were with individual hosts. For individual hosts who had at least one listing in 2019, the average number of listings was 1.3," Airbnb said.

Big Comeback Story

Even before Covid-19 wreaked havoc on Airbnb this spring, the company faced substantial challenges. Some research indicated that its growth rate in its core short-term rental business in various markets around the world was slowing as regulators from Barcelona to Paris and New York City got bolder and intervened.

Airbnb layed off 25 percent of its workforce in the Spring, took on $2 billion in debt from private equity firms, repayable at high interest rates, and global bookings slowed to a trickle.

Up until then, liquidity hadn't been a major issue for Airbnb, which announced in 2019 that it intended to go public this year. Airbnb raised some $6.4 billion from high-profile venture firms such as Sequoia Capital, Greylock Partners, Andreessen Horowitz, General Catalyst Partners, and dozens more. Airbnb has acquired more than 20 companies along the way including, HotelTonight, Luxury Retreats, Accomable, and CrashPadder.

CEO Chesky had been in the midst of preparing the paperwork for an initial public offering, and possibly readying the launch of a flights product to go along with hotels, experiences and multi-day tours, when the coronavirus pandemic seemed to sabotage those plans.

He announced at that time that the transportation offering had been sidelined, as had ongoing investments in ramping up the hotel product that had been spearheaded by its 2019 acquisition of HotelTonight.

The IPO push pre-Covid was geared mostly to enable employees to exercise soon-to-expire stock options, rather than needing to raise a huge coffer of funds.

Anyone viewing travel demand in the West in March 2020 would have given Airbnb little chance of going public in 2020. But bookings for the alternative accommodations' sector, particularly in non-urban areas, rose sharply this summer, putting an Airbnb stock listing back on the table.

Although Expedia's Vrbo, growing from a much smaller base and because of its whole-home bent in non-urban areas, seemed to be the category's growth leader in the United States, particularly in the second quarter, and into the third, Airbnb came back strongly, as well.

In a major comeback story, Chesky took his S-1 draft out of a drawer or folder, and filed it with the Securities and Exchange Commission on a confidential basis in August, which led up to initial public offering registration statement becoming public today.

Memories of those air mattresses in San Francisco are a nostalgic bit of business history now.