Ireland’s Tourism Success Is Under Threat by Brexit: A Skift Deep Dive

Skift Take

The only indication that you’re crossing over a border is a slight change in the color of the road surface and a different road sign. Nothing else. The green fields, the cars, the sky, and the houses are the same wherever you look.

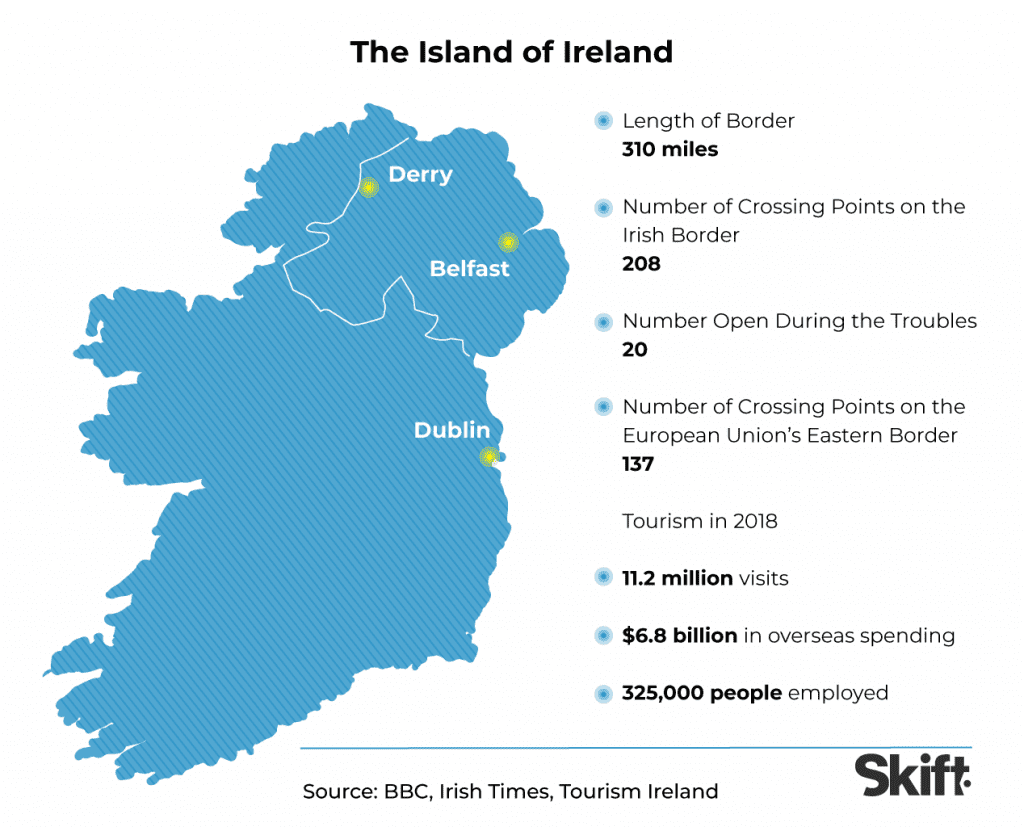

Racecourse Road, just outside Derry, is one of the 208 crossings between Ireland and Northern Ireland. These days the checkpoints that became such a visible symbol of the split between north and south are long gone, but a unique set of circumstances has brought the border back into question.

Since the 2016 referendum, Brexit has consumed UK politics. Last Tuesday, MPs rejected for the second time the agreement Prime Minister Theresa May struck with European leaders, and there is still uncertainty on how, when, or even if the United Kingdom will leave. One thing, however, is for sure: Leaving the European Union will have significant consequences on both sides of the border.

Tourism is an industry that relies on the smooth movement of people, something the EU, with its abolition of internal borders, has helped facilitate. The United Kingdom’s increasingly acrimonious departure puts all this in jeopardy, with some suggesting it could cost the Irish sector more than $430 million (€384 million). Not only that, but the specter of violence looms large once again.

Irish tourism has performed remarkably well in recent years, but Brexit, and all that it entails, could threaten everything.

Tourism on the Island of Ireland

To get a sense of the peculiar way the island of Ireland is marketed as a destination, you’ve got to go back in time. Up until 1921, Ireland was one country and still part of the United Kingdom. Partition split it up into two entities, Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland. Northern Ireland — made up of six of the nine counties in the province of Ulster — was predominantly Protestant, while Southern Ireland was mainly Catholic.

Despite a desire for independence, both Irelands were part of the United Kingdom. This didn’t last long, and after the Irish War of Independence, the Irish Free State — eventually renamed Ireland — was born. The problem for those who wanted a united Ireland was that a majority in the north didn’t want the same thing and so opted out.

This state of affairs has lasted almost 100 years and, for a large part of the twentieth century, resulted in plenty of bloodshed.

In 1998 the United Kingdom, Ireland, and politicians in Northern Ireland signed the Good Friday Agreement, a major milestone in the peace process. The agreement identified six areas of cooperation between Ireland and Northern Ireland, one of which was tourism.

The idea was that a single organization, Tourism Ireland, would market the destination of Ireland internationally while working with the two tourist boards on the island.

“It basically meant that the jobs that were being done separately by the Northern Ireland tourist board [Tourism NI] and the Irish tourist board [Fáilte Ireland] are now done by the one company. We work seamlessly internationally,” Tourism Ireland’s CEO Niall Gibbons said.

The coordinated approach has helped both jurisdictions, but there was a much bigger reward.

The Peace Dividend

Up until the peace process kicked in during the 1990s, travel between the two Irelands was much more difficult than it is today. Checkpoints and road closures were a fact of life for those people crossing the border. And although there are still outbreaks of violence, it is not at the same level seen throughout the period known as The Troubles.

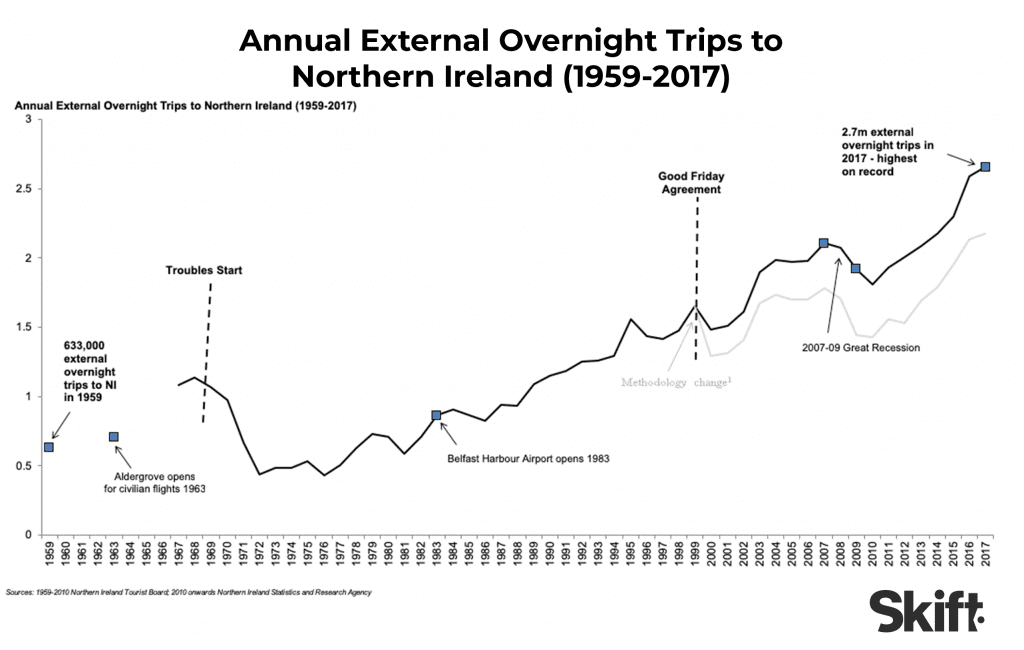

It is impossible to quantify the benefits of peace and remove them from wider macroeconomic factors, but it makes sense to assume that tourism, especially in Northern Ireland, has benefited.

“I suppose the biggest transition of the Good Friday Agreement was peace and…being able to sell Ireland as an all-Ireland experience with less concern for overseas visitors and actually crossing that border and going to the north of Ireland,” said Ruth Andrews, special advisor to the Association of Visitor Experiences and Attractions.

“Peace has meant that it’s brought confidence over time to international visitors to being less uneasy about traveling to the north of Ireland.”

Eoghan O’Mara Walsh, CEO of the Irish Tourism Industry Confederation (ITIC), agrees.

“All you need to do is look back 20 years ago, when the peace process started. So prior to that tourism numbers were much fewer into Ireland, both north and south. And since then the tourism numbers have — okay we’ve had ups and downs and stuff — but overall tourism numbers are in a much more healthy position,” he said.

“And that’s partly because we’ve been able to market the island overseas as a single destination, but also the fact that there is no border, and literally you drive from Dublin to Belfast without even knowing you’re going from one jurisdiction to another.”

The island of Ireland is certainly in a good place in terms of tourism. Numbers have grown steadily since the global financial crisis of 2008–2009, and a host of new openings have helped generate a buzz around areas that were maybe not as familiar to overseas visitors.

Fáilte Ireland launched the Wild Atlantic Way in spring 2014, a touring route that stretches from Cork in the south to Donegal in the northwest. Ireland’s Ancient East followed in 2015, and in 2018 came Ireland’s Hidden Heartlands, a brand campaign featuring the Midlands region.

“There’s absolutely no doubt that by creating the destination brands here in the Republic…that just makes it more apparent to the visitor of what there is to do and see. It brings those parts of the country to life, if you like, because [of] the stories we can tell around them and how we can then help to actually spread tourism,” said Andrews, who is also CEO of Ireland’s Incoming Tour Operators Association.

Northern Ireland has also had a couple of big openings in recent years. The Giant’s Causeway cut the ribbon on a new visitor center in 2012, the same year Titanic Belfast, a monument to the city’s maritime past, opened. There has also been a steady influx of visitors keen to see some of the locations used for filming HBO’s Game of Thrones TV show.

In 2017 the external tourism market, including Great Britain and Ireland, contributed $865 million (£657 million) to the Northern Irish economy, up 7 percent over the previous year.

“[O]ur ambition would be to see the value tourism in Northern Ireland double over the next decade in the same way it did over the past decade. There’s no reason why that shouldn’t happen,” John McGrillen, Tourism NI CEO, said.

Across the whole of Ireland, 2018 was another record year for tourism, with 11.2 million people visiting and an overseas tourist spend of $6.8 billion (€6 billion). Compare this to 2009, the year after the financial crash, when overseas visitors totaled 7.6 million and brought in $3.8 billion (€3.4 billion). In less than a decade, numbers have risen 47 percent, while spending is up 76 percent, without adjusting for inflation.

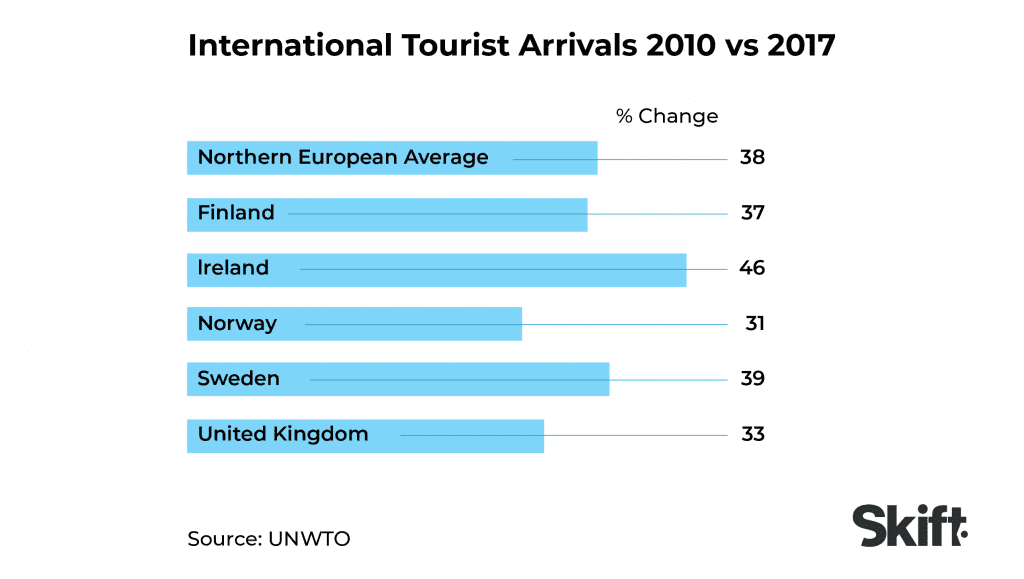

Of course, this success isn’t due solely to Ireland and Northern Ireland’s unique pulling powers. The wider economic growth enjoyed by many since the financial crisis has helped, and other countries have similarly experienced significant growth.

Thanks to its long history of emigration, Ireland is a beacon to many who long to revisit their ancestors’ homeland, and moreover, Aer Lingus — now in much better financial health — has strengthened its transatlantic business.

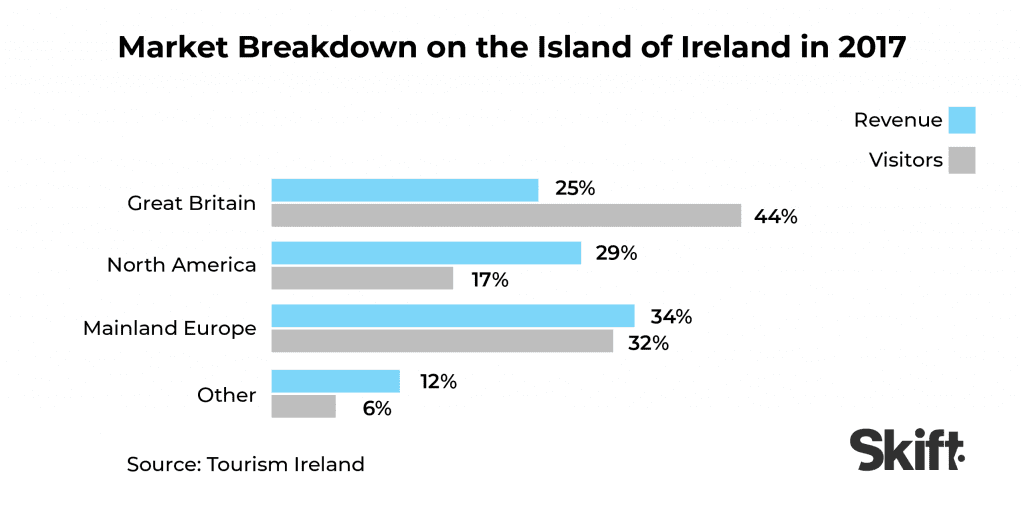

A key factor of Tourism Ireland’s strategy is attracting more European visitors, which makes it less reliant on the British market. “[T]hat started back in 2014. That’s when we started on the path to market diversification and…reducing the heavy reliance there was on the GB [Great Britain] market. To the point now where GB is still really important for us, really important volume market, but in terms of the holiday revenue, when you get down to holiday makers it’s about 18 percent of the total spend,” Gibbons said.

Great Britain — which is England, Scotland, and Wales — still made up 44 percent of the Ireland and Northern Ireland’s visitor numbers in 2017 and 25 percent of all revenue, or $1.6 billion (€1.4 billion) — not an insignificant sum.

The Backstop

Over the last couple of years, what is known as the Irish Backstop has played a key role in Brexit negotiations — and the subsequent disagreements. Essentially it is a fail-safe mechanism that kicks in under a special set of circumstances in order to keep the border between Ireland and Northern Ireland open.

The United Kingdom — including Northern Ireland — is leaving the EU and its customs union, but Ireland will still be a part of both. So there would be two different rulebooks on the island of Ireland. After a two-year transition period, the idea, in theory at least, is that the United Kingdom and European Union would secure a trading deal, thereby keeping the border open.

But what happens if the two sides don’t agree to a deal? Well, Prime Minister May and her EU counterparts have negotiated this backstop, which would see Northern Ireland stay closely aligned with the EU and therefore its southern neighbor. A lot of people hate this, and it’s one of the reasons why May has struggled to get parliamentary approval for her deal, which, at the time of writing, she is still trying to secure.

“The trouble is you either have a customs union and no border, or you have no customs union and then we have a border, it’s very simple,” economist Clemens Fuest, president of the IFO Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich, said.

Almost nobody wants a return to a hard border. In the event of a no-deal Brexit, the United Kingdom said it would not impose border controls, but its recently revealed solution is one-sided and temporary. Of course, were May to get the deal through the Houses of Parliament, then the border threat would diminish. At the same time, that threat might not go away entirely because the whole process of the United Kingdom leaving has become so acrimonious. There would still be a risk for an accidental no-deal even if the European Union grants the United Kingdom an extension.

What is perhaps more disturbing is that Brexit tensions have once again inflamed tensions over the status of Northern Ireland.

And herein lies the problem: Tourism Ireland markets the island of Ireland, and that includes Northern Ireland, which is part of the United Kingdom. This arrangement worked fine when both were part of the European Union, but from March 29 of this year, this will cease to be the case if the EU doesn't agree to a deadline extension. If Prime Minister May secures a deal, the United Kingdom will avoid the very worst-case scenario, but if not, we’re in uncharted territory.

There are two massive problems. The first is economic. If the United Kingdom — and this includes Northern Ireland as well — crashes out without a deal, there is the very real possibility of a recession. What will this mean for the island of Ireland?

Remember that Great Britain made up a quarter of all tourism spending in 2017. If those visitors cut back — something that hasn't happened so far — the island of Ireland could take a serious hit. Fáilte Ireland deems the risk serious enough that it is putting $5.7 million (€5 million) into a fund to help businesses prepare for Brexit.

“As we await the final outcome of Brexit, and with the situation changing on a daily basis, it is still difficult to quantify the range and scope of impacts that Brexit will have. Our key message to tourism businesses is ‘prepare and diversify,’" said Paul Kelly, Fáilte Ireland CEO.

"Any tourism business which does not have Brexit contingencies as a central focus of its 2019 business plan needs to act fast."

Ireland — as opposed to Northern Ireland — could also suffer if the the value of the pound falls even further in the coming months, making the United Kingdom a more attractive destination for overseas tourists.

The second big issue is what, in fact, will actually happen to the border.

The Walled City

The city of Derry lies on the banks of the River Foyle in the northwest corner of Northern Ireland, just a few miles from the border. It was built with money from London guilds, which gave it the name Londonderry, although most people just call it Derry.

In 2013 Derry became the United Kingdom’s first City of Culture, and this year will mark the 400th anniversary of the famous walls that surround it.

The city’s more recent history is tied up with The Troubles. In 1972 it was the site of the Bloody Sunday massacre, one of the ugliest episodes of the conflict, where British soldiers shot and killed 14 innocent civilians. Derry’s proximity to the border makes it a potential flashpoint for Brexit negotiations.

Paul Doherty runs Bogside History Tours, an operation unafraid to deal head-on with the city’s difficult past and its relationship with the rest of the United Kingdom.

“The British aren't really used to people telling them what to do and telling them they can’t do whatever, because they just got away for centuries of colonialism and imperialism,” he said.

And this intransigence could have a knock-on effect on people living in Derry and elsewhere: “The worry for me is tourism, obviously. I mean, is tourism going to be affected by big queues of traffic on the border? And if there are queues of traffic on the border, people will be more reluctant to sit in maybe an hour or two of traffic. Nobody really knows.”

A border would likely harm Derry’s push for tourism growth, and it wouldn’t be the only place caught up in the battle between the United Kingdom and European Union.

Northern Ireland’s border with Ireland is 310 miles long. Given the history and the difficulty of erecting a border, it seems insane that it is even up for discussion. Whatever happens, passport checks probably wouldn’t be necessary, but any form of border would have a psychological effect. Even talking about it as an issue has proved divisive.

JJ O’Hara and his family run a number of tourism businesses in County Leitrim close to the border with Northern Ireland. He is also part of a community group called Border Communities Against Brexit.

He said that bookings from English tourists were down about 12 percent. O’Hara attributes this decrease to the exchange rate and to people not feeling welcome.

Dublin and other parts of Ireland might be insulated from this type of uncertainty, but for people like O’Hara who live and work close to the border, it poses a very real threat. “[P]eople they’re afraid that there’ll be any backlash if any border goes up. The local people are not accepting of any type of border,” he said.

O’Hara’s company is building a $4.5 million (€4 million) holiday village, which he said was now in “jeopardy” because of the Brexit uncertainty and the impact it might have on the tourism market.

It also threatens to turn back the clock to a time when there wasn’t peace on the island of Ireland. “We don't want the British helicopters in the air and 20,000 soldiers on the ground again. The bombing — I mean, no one wants to live through that again. The blown-up bridges, the blown-up roads,” he said.

Winter Is Coming

If some kind of border does reappear, it would make things much tougher for Northern Ireland in particular. That’s because most of the international arrivals come through Dublin, thanks largely to Aer Lingus’ expansion since joining International Airlines Group in 2015.

The carrier offers 15 North American destinations, bringing a steady influx of tourists from places like New York, Philadelphia, and Seattle. In contrast, Belfast’s only transatlantic route is a seasonal service to Orlando, which mainly caters to customers going from east to west.

And although Tourism Ireland has marketed the island as one destination since the Good Friday Agreement, the southern part of the island is the main focus. Interestingly, however, the most visited attraction for Chinese visitors — a target group for any destination — is actually the Giant’s Causeway in the north.

The new Giant's Causeway Visitor Center opened in 2012 and received $7.9 million (£6.1 million) in European Union funding.

According to Tourism Ireland, two thirds of the North American and European visitors coming to Northern Ireland come via Ireland. A hard border would make the destination a more difficult sell.

Phil Ryan, one of the owners of Inroads Ireland, a tour operator specializing in trips around the island, said he has already seen a drop in interest in the company’s northern tours, especially compared with those that run in the west and south.

“I’m putting that down to just sort of negative press in regards to Brexit, and people just don’t know what’s happening, you know. This sort of confusion, uncertainty, they don’t know what their dollar is going to [do] or [if] it’s going to be euros or pounds, that kind of thing,” he said.

Given the confusion surrounding the border and what is going to happen with Brexit, Ryan said it made planning trips more difficult.

“[Y]ou have the common travel area, so that basically means you can go between the north and the south without any real issue, but if you happen to have extra paperwork just to cross the border — even if it is an imaginary border — that sort of adds extra complexity and makes things a little harder going forward,” he said.

“It does make you wonder, for the few days that we spend there, is it worth continuing to go into the [North]?”

A border wouldn’t just make it physically more difficult to get between the north and south. There could also be the possibility of a divergence in regulations that could affect things like coach vacations.

“In real terms without a withdrawal agreement, the United Kingdom would no longer be a member of the EU customs union, and that will cause extreme difficulties for our members,” Kevin Traynor, national director of Coach Tourism and Transport Council of Ireland, said.

“Particularly if there’s a hard border and effectively we go back to the regime where we have a customs clearance and customs officials. It will cause excessive delays, increased journey times, it’ll increase costs particularly in the area of administration.”

Bigger Problems

Looking at all this, it’s easy to feel pessimistic about tourism on the island of Ireland — especially in the north and the border areas in the south — but Brexit isn’t the only uncertainty hanging over the industry in 2019. There are other factors that some people think may play a bigger role.

It’s worth remembering that Ireland isn’t the only country that has enjoyed a tourism boom since the financial crisis. Most of the world has seen increased demand. Ireland and Northern Ireland are therefore not unique. Iceland, for example, has seen a 355 percent rise in tourism numbers since 2010, according to the United Nations World Tourism Organization.

“I’d be very much of the view that macroeconomics, as an economist, matter an awful lot,” Professor Jim Deegan, director of the National Centre for Tourism Policy Studies at the University of Limerick, said.

“And therefore, to me, GDP growth in other markets, exchange rate changes in other markets, are very, very important. The branding, the marketing matters…in my view. But if I was putting money on what matters most for Irish tourism, I would always bet on the macro economy and exchange rates.”

Deegan said that deteriorating issues between Italy and France and between the United States and China are potentially more concerning for global tourism.

“So, there are circumstances that we haven’t seen for some time, where both internationally and at the European level, that these factors could significantly impact upon tourism. And in my own view, these factors, ironically, might turn out to be much more of greater importance for the medium term in Ireland, than will the Brexit downturn,” he said.

Within Ireland itself there are also potential problems. The country’s government increased the rate of VAT on tourism services by 50 percent, which equated to a $521 million (€466 million) hike.

“[W]e’d be very critical of the government in regards to their taxation policy in relation to Irish tourism in the last budget. And we argued, and unfortunately it’s been unsuccessful so far, but we’ve argued that that hike should be deferred by at least 12 months to allow the shape of Brexit to come to pass,” ITIC’s O’Mara Walsh said.

"So, if it’s a soft Brexit or a hard Brexit or a mediocre Brexit, at least we’d know the lay of the land, before you start hiking tax rates on a vulnerable sector."

In Northern Ireland, there’s another issue that campaigners believe is hurting the tourism industry: air passenger duty (APD).

The aviation industry across the United Kingdom likes to blame this tax for all manner of ills — including the recent collapse of Flybmi — but the government has so far been reluctant to abolish a guaranteed stream of cash. The situation, however, is more acute on the island of Ireland, where there are two different rates and only 100 miles between Dublin and Belfast international airports.

“[W]e believe that with further investment in new product and new visitor attractions, and if we could resolve the APD issue and get current activity from the airlines, there’s no reason why we could not continue to grow at five and six percent per annum,” Tourism NI’s McGrillen said.

The government abolished APD on long-haul routes in Northern Ireland in 2013, but it still exists on short-haul European routes and adds an extra $18 (£13) per flight.

“It’s a short hop and that tax is significant. In my view, it impacts upon our competitive advantage or creates a competitive disadvantage,” he said.

“But, I think the other challenge is, if people are coming from Europe, they tend to be coming for a very short break. They tend to stay, typically, close to where they land, and therefore getting people into Belfast directly is important to get people to spend more time in Northern Ireland.”

An Unwelcome Return

For most people living in and around the border, a return to the checkpoints and customs offices of the past seems inconceivable. But with the United Kingdom still undecided about what type of Brexit it wants, uncertainty about the fate of the border is at a high level. Even with a Brexit deadline extension, the clock would still be ticking. And we should remember that even if Prime Minister May gets her Brexit deal through, there are still further hurdles to overcome and the possibility that in two year’s time after the transition period, we return to the same arguments.

Crossing the border in Ireland is as easy as getting in your car and driving to the other side, but it wasn’t always the case. There was a time before the peace process and the Good Friday Agreement when getting across was much more difficult. With the majority of North American and European tourists entering the Emerald Isle through the south, Northern Ireland could lose out on major tourist growth for the next decade should Brexit complicate border crossings once again.

“Years ago, what you had in that back road when the conflict was on, was big concrete-filled metal containers called dragon’s teeth, where you couldn’t physically drive over the border. You could walk over it and jump over it. All barbed wire and all the rest, you know?” Doherty said.

Whatever happens with Brexit, it’s brought back some unpleasant memories and risks fracturing the very industry that the island of Ireland has worked so hard to build as a single destination.

Update: Fáilte Ireland launched the Wild Atlantic Way and other destination brands.