Skift Take

The Green Book helped black Americans move about safely during segregation, but it also sparked the growth of black leisure travel and fueled entrepreneurship in the community for years to come.

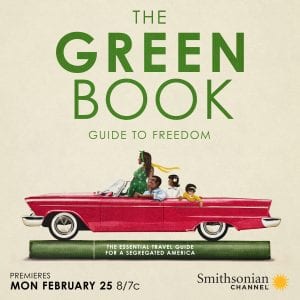

A new Smithsonian Channel documentary about the Green Book — which helped black Americans travel safely during segregation — goes deep into the early, successful entrepreneurship behind the business of black leisure travel.

In mainstream culture, The Negro Motorist Green Book is now enjoying a resurgence of interest, most visibly in the film Green Book, which is up for several Academy Awards, including best picture. The Smithsonian documentary set out to delve deeper into the factual history of the subject.

“Victor Green knew there were enough black people in the country who would not only use this guide for safety, but wanted this guide for pleasure,” said author Candacy Taylor in the film. “He knew his market. He was a businessman.”

The documentary, The Green Book: Guide to Freedom, written and directed by Yoruba Richen, premieres on February 25 at 8 p.m. EST on the Smithsonian Channel.

The documentary, The Green Book: Guide to Freedom, written and directed by Yoruba Richen, premieres on February 25 at 8 p.m. EST on the Smithsonian Channel.

The Green Book arguably addresses safety first, but it also propelled incredible growth in black leisure travel. The book provided listings of hotels, restaurants, and gas stations that welcomed black clientele in an era when lynchings were rampant, sundown towns didn’t allow black people after dark, and many businesses were whites-only. The book was first published in 1936 by postal worker Victor Green in Harlem, New York.

Even though Nat King Cole performed the song Route 66, he couldn’t stay at many of the establishments along it: 44 of the 89 counties along the Mother Road contained sundown towns. Black road trip accidents actually spiked during this era according to one local sheriff, because of the fatigue related with being unable to stop for the night.

“For most African Americans, regardless of class, there was always some sense that things could go terribly wrong,” said Allyson Hobbs, associate professor at Stanford University, to Skift. “At best maybe you get pulled over and get a speeding ticket. Or maybe you get pulled over and get harassed, or you’re humiliated in front of your family. Maybe you stop at a restaurant or hotel and they won’t allow you to stay there. Maybe you stop at a gas station and they won’t let you get gas or use the bathroom.”

The Business of Black Leisure Travel Takes Off

The Green Book proved so useful and popular that Green expanded his business model. In 1948 he added a travel service through which readers could book reservations for businesses listed in the guide, and thereafter, resorts catering to black travelers flourished: American Beach in Florida, Atlantic Beach in South Carolina, and Murray’s Dude Ranch in California.

Idlewild, the iconic black resort in northwest Michigan, took off during this time as well. Much of its success hinged on having its own black-owned gas station and other businesses, and a safe space for black vacationers to swim when integrated public pools were a hotbed of controversy.

The A.G. Gaston Motel is also among the most famous Green Book establishments, located in Birmingham, Alabama, and its design was based on the Holiday Inn chain, to create something like accessible luxury. A.G. Gaston lived to 103 and his net worth at the time of his death in 1996 was over $40 million.

Behind all this growth was a trend that white America didn’t see coming: “Regular people populating something called the middle class, taking time to have excursions across the nation, to go to Yellowstone Park, or to go down to the beach,” said Marquette Folley of the Smithsonian Institution.

Interestingly, North Dakota resisted listing any businesses in the Green Book, claiming that there were not enough black tourists for it to make sense.

After legal segregation ended in 1964, black travel businesses saw a dip in business as black travelers were slowly but increasingly allowed to stay in white-owned establishments. Those white-owned businesses had much more money to work with and black businesses struggled to compete.

Decades later, black leisure travel looks very different. The black travel movement itself is like a modern-day equivalent of the Green Book, a digital space in which black travelers share information about safety, acceptance, and pushing boundaries — which airlines treat black flyers well, and which homeshares allow black vacationers to book and stay without harassment or denial of service. In fact, both the Green Book and the modern-day black travel movement are rife with female entrepreneurs.

The Daily Newsletter

Our daily coverage of the global travel industry. Written by editors and analysts from across Skift’s brands.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: black travel movement, civil rights, road trips

Photo credit: Carol Jenkins, the niece of A.G. Gaston, stands in front of the famous A.G. Gaston Motel, a major listing in the Green Book. Smithsonian Networks