Skift Take

Aviation has terrible gender optics, and not just with pilots and engineers. The C-suite is nearly void of women for flimsy, unacceptable reasons. In this deep dive, women on the commercial side of aviation share how it feels to hit the glass ceiling in 2019, and occasionally break through.

Of all the sectors in travel, aviation has one of the most glaring gender gaps. The image of a male pilot and a female flight attendant has long been standard, and the executive ranks don’t look much different.

Very few women occupy airline c-suites, even now, as the Time’s Up movement shines a light on gender inequality in the workplace. Just 3 percent of CEOs in aviation are women, compared to 12 percent in other industries, according to the International Air Transport Association.

“We’re in 2019, and we are not moving as quickly as we should,” said Christine Ourmières-Widener, CEO of UK carrier Flybe and one of the most prominent female airline CEOs today. She added that we should not, and need not, wait another generation or two to achieve gender parity.

The industry’s response is just as lackluster as the numbers themselves. American Airlines, United Airlines, Delta Air Lines, Southwest Airlines, and JetBlue Airways — all of which have male CEOs — all declined to comment on the importance of pursuing gender parity, or the importance of male mentorship.

IATA, whose CEO is also male, declined a dialogue as well, despite that its own research illustrates the sad state of affairs. The closest thing to a comment Skift received was from a Southwest spokesperson: “We have a few efforts in the works, but nothing ready for prime time.”

So why are airline executive suites such a closed shop for women? In some ways, the problem is familiar. A lack of female executives means fewer role models and fewer paved paths to the top.

But aviation is also a STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) field, and this complicates recruitment on both the commercial and technical sides of the business. The path to becoming an airline executive is very different than becoming a pilot or an engineer, but the two career paths do have something in common: For many women, the entire field presents anywhere from unfamiliar to openly hostile.

“It’s a business that revolves around big boys’ toys, engineering, and industry regulation. The only areas where women have a large role is at check-in and serving in-flight meals. At least that is the perception,” said a report from aviation intelligence provider CAPA. Fortune magazine ranked Delta Air Lines No. 26 on its list of 100 best workplaces for diversity, citing that its workforce is a striking 41 percent female, the highest percentage of any airline on the list — but this figure doesn’t show how few women are employed at senior levels.

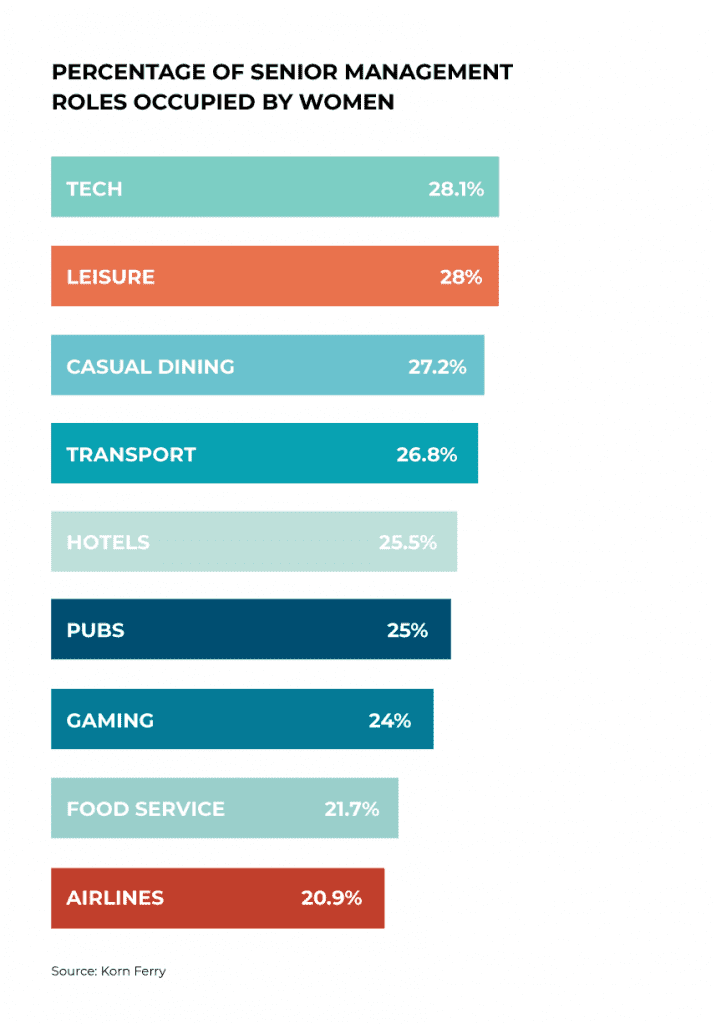

In 2018, CAPA found that only 6 percent of airlines globally had appointed women to senior executive positions, and between 2010 and 2015, the number of female CEOs and managing directors barely rose from 15 to 18. Of all the sectors in travel, leisure, and hospitality, airlines had the lowest percentage of women occupying senior manager positions at 21 percent, according to a UK-focused report by management consulting firm Korn Ferry.

Ourmières-Widener of Flybe has ample experience on both the commercial and technical sides. Formerly she was CEO of Dublin-based airline CityJet, and an engineer at Air France working on the famous Concorde, before which she earned a master’s degree in aeronautics and an MBA. She said both the commercial and technical career paths feel foreign to many women, but this isn’t insurmountable.

Christine Ourmières-Widener (right) studied both the commercial and technical sides of aviation. Photo by Flybe.

“You don’t have to be an airline geek to manage an airline,” said Ourmières-Widener, citing easyJet’s former CEO Carolyn McCall as evidence. McCall was once one of the most well-known female CEOs in aviation; after seven years she left easyJet in 2017 to join UK broadcaster ITV. Kuwait Airways also had a female CEO for three years, Rasha Al Roumi, who departed in 2017. Both women were replaced by men.

Then again, some women simply don’t want to join what appears to be a hostile boys club. Qatar Airways CEO Akbar Al Baker famously said a woman couldn’t do his job at a press conference following an IATA meeting in June. Years of objectifying imagery coming out of Virgin, featuring Richard Branson touching and leering at female flight attendants, make for bad optics as well.

There could be two promising paths to diversifying the upper ranks of aviation in a long-term way.

The first involves active recruitment of women into the executive pipeline accompanied by mentorship — male mentorship being indispensable. The second requires even more patience: introducing aviation into the lexicon of young girls so that when they are considering careers, it appears on their radars like any other field.

Maybe within the next 20 years there'll be some women in the photo! https://t.co/lemEYRDfJx

— Kerry Reals (@KerryReals) February 1, 2019

Women Still Have to Make the Business Case for Diversity

One persistent problem is having to make the business case for diversity, despite how well-documented it is.

Companies in the top quartile for gender diversity are 15 percent more likely to have financial returns above their respective national industry medians, according to a McKinsey report. Plus, in the UK, greater gender diversity among senior executives corresponded to the highest performance uplift in the data set: For every 10 percent increase in gender diversity, earnings before interest and taxes rose by 3.5 percent.

“If more women occupied the U.S. airlines’ executive suites, I doubt you would have seen LeggingsGate, StrollerGate, or the recent Delta fiasco where a family was kicked off an overbooked flight because one of their children’s seats was resold,” said Kendall Creighton, communications director at passenger advocacy organization Flyers Rights, to Runway Girl Network.

Leaving women on the sidelines means that aviation is opting into a half-size workforce, according to Sara Nelson, international president of the Association of Flight Attendants. Nelson reported hearing from men: “Wow, I thought I was progressive and forward-thinking, but it never occurred to me that this would double the size of the workforce we’re trying to attract.”

“That is exactly why you need women in executive positions,” said Nelson.

Women Still Hit a Disrespectful Glass Ceiling

Even with evidence that female executives are good for business, women must still convince men to take them seriously, according to Rexy Rolle, vice president of operations and general counsel at Bahamian airline Western Air.

Rolle said she once walked into a civil aviation meeting, made a pitch, and was answered patronizingly by a man who began his rebuttal, “Well, sweetheart …” Rolle said that early in her career, “There definitely was a sentiment of ‘This is a young little girl, what is she doing telling me that I’m wrong, or telling me that she should be provided x, y, and z?’” Rolle said she has received many other demeaning gender- and age-based comments throughout her career.

Rexy Rolle of Western Air sees more gender-based discrimination than racial discrimination. Photo by Rexy Rolle.

Rolle is even more of a rarity than a woman running an airline — she’s a black woman running an airline — but she said that gender discrimination was actually a bigger problem for her than racial discrimination. This may result from her being based in the predominantly black Bahamas.

With so many male gatekeepers, being taken seriously is crucial to getting the green light on a project, or landing the next promotion. Liliana Petrova, former JetBlue director of customer experience, was active in JetBlue’s female mentorship program and rose up the ranks over seven and a half years, but ultimately, JetBlue did not allow her to advance to the more senior level for which she was poised. “What they gave me was a VP job, but they didn’t [actually] make me VP,” said Petrova. “Now I’m a VP at a different company,” she said, having joined the food industry.

“You’re treated as if you’re one of the assistants or a secretary. You’re not taken seriously and you feel really boxed out,” said Creighton about attending the Aircraft Interiors Expo, a major show with serious potential for career advancement. She said the attendees of this show are, famously, almost all white men. Basic networking, much less finding a mentor, has been difficult for her. “Kendall is usually considered a male name. Then all of a sudden I’m left out in the cold when they find out this is a woman,” she said.

Kendall Creighton of Flyers Rights has struggled to crack the boys club at trade shows. Photo by Kendall Creighton.

“Surprisingly, my fellow male aviation journalists are the most disrespectful,” Creighton added by email, having referenced an exclusive, boys club atmosphere. “The culture is vastly anti-female and culminates up to the executive suite level.”

Similar frustrations cropped up for Nelson of the Association of Flight Attendants. Nelson told Skift about being the only woman in a roomful of men, being asked to explain to men — on behalf of all American women — why some didn’t support Hillary Clinton, and hearing a man declare that there could never be a female president of the AFL-CIO.

At earlier stages in her career, when a conversation would get especially technical, Mylène Scholnick had to really emphasize her credibility in order to be taken seriously in a room full of men — she’s a senior advisor at consulting firm ICF and an advisory board member of the International Aviation Women’s Association. Scholnick even knows what it’s like to be the only woman at a 30-person dinner. “It’s the old men’s club. It’s always been that way.”

Scholnick noted that having children can be a major barrier for some women on the executive track — without a robust support system at home and at work, women may be forced to pull back considerably or even drop out of the workforce. On the other hand, she also believes in empowerment from within. “We need more grit and more guts to be able to get there,” she said of the c-suite.

“The system is not helping, but we have to be a little bit stronger,” said Scholnick.

Richard Quest: six men in suits will now discuss gender equality. #IATAAGM pic.twitter.com/HARL50vImb

— Will Horton (@winglets747) June 4, 2018

Aviation Has a Visibility Problem in Business School

Business school is an important pipeline for the c-suite, but unfortunately, aviation is often not part of the career-development conversation for women.

Women entering the commercial side of aviation “have the same problem as engineers: There are simply not a lot of women there,” said Dawna Rhoades, professor at the David. B. O’Maley College of Business at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University. She said only about 27 percent of the entire university’s students are women. “We don’t have a problem getting women from India and China that have very technical backgrounds,” she said, noting that growth in female faculty outpaces growth in female students.

“When I came here in ‘96, I could count the number of female faculty across this campus who had a Ph.D. on tenure track on one hand.” Today, about half of the faculty in her department — which is management, marketing, and operations — are women.

Madison Dietrich pursues a B.S. in aviation business administration at Embry-Riddle. Photo by Embry-Riddle/Connor McShane.

“Aviation is not well-known as a career path if you compare it to technology, to banking, to consulting,” said Scholnick of consulting firm ICF. She noted that many in the industry are trying to promote lesser-known aviation jobs in finance and marketing. On the other hand, she said that in countries like Kenya and Ethiopia, aviation is actually a much more visible career path, in part because there are fewer careers from which to choose.

“I don’t hear them say airline very often. It would have to be prompted,” said Carolyn Goerner, clinical professor of management at the Indiana University Kelley School of Business, about her female students. This is partly because some business school students don’t have a clear idea yet of their preferred field, but also because aviation is more complex, legally and operationally, than many manufacturing businesses. She said it would be easier for many students to consider working at Boeing than, for example, American Airlines.

Familiarity is crucial for the direction a career takes, and airlines don’t feel familiar to enough women in business school, especially foreign airlines, said Goerner. And if a female student does have that familiarity, or the willingness to go the extra mile to get acquainted, she will need confidence to spare.

One of the top questions Goerner has for female students considering a male-dominated field is, “Are you sure you’re OK with the scrutiny that will bring? She’s going to get more attention just by nature of who she is.”

✨✈️🏆 Congratulations to all of the Crystal Cabin Award winners! Here's the full list: https://t.co/bSwhqo9YKw #CCA18 #CCA2018 #AIX18 #AIX2018 #PaxEx #AvGeek #innovation @HamburgAviation @aix_expo pic.twitter.com/XyI1vg1l6H

— APEX (@theAPEXassoc) April 11, 2018

Male Mentors Are Indispensable

When a woman is working at an airline, mentorship on three separate levels is key, said Goerner of Indiana University: having a senior male mentor to signal the mentee’s qualifications to other men, working with women higher up on the ladder (if there are any), and having a safe space with peers.

Flybe CEO Ourmières-Widener echoed that a mentor — who isn’t a supervisor or a friend — is crucial, and that mentor is likely to be a man in aviation. In addition, all of her mentors except one were men, and they helped her develop.

When supporting women as they climb up the corporate ladder, “It’s really important for men to be the loudest,” said Rexy Rolle of Western Air.

What’s just as important is that those male mentors allow women to land speaking roles at conferences, interview opportunities, and other chances to make their faces known so they can enter that executive pipeline. Ourmières-Widener said the talented women are there, they just don’t make it onto the executive track for lack of visibility afforded by delivering public presentations.

Signals from male CEOs are important. Carolyn McCall’s male replacement at easyJet, CEO Johan Lundgren, took a 4.6 percent pay cut to match his predecessor’s salary — more meaningful would have been to raise women’s salaries to match their male counterparts.

The culture at JetBlue was generally supportive for Liliana Petrova, its former director of customer experience, and she participated in a female mentoring group she described as “like therapy.” But, JetBlue was lacking in other ways.

“We had a very supportive group of men, but one section of the group had that boys club thing,” said Petrova. “We were never not taken seriously, it was more that we hit the ceiling,” she said, finding ample support for her ideas and projects in JetBlue President and COO Joanna Geraghty.

Me Too Backlash Causes Gender Segregation at Senior Levels

There’s new tension surrounding male-female mentorship in the era of Me Too, in which male celebrities have been publicly dethroned by their assault victims. As a result, some high-profile men will no longer take on female mentees, for fear of a career-ending accusation. This fear was discussed at Davos and echoed by U.S. Vice President Mike Pence.

This growing fear is turning into paranoia and strict gender segregation, which is hampering women’s professional progress. Some male executives now see women as trigger-happy false accusers whose primary objective is to remove men from power, when in fact, Me Too is about protecting women from assault.

“That really is a guilty conscience,” said Nelson of the Association of Flight Attendants about men claiming that Me Too is an attack on men.

The number of male managers who are uncomfortable mentoring women has more than tripled from 5 to 16 percent in the era of Me Too, according to a 2018 survey by Lean In and Survey Monkey. Fewer than two-thirds of survey respondents said a work meeting alone with a member of the opposite sex was appropriate, according to research conducted by The New York Times and Morning Consult.

Dawna Rhoades of Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University hasn’t seen male mentorship decline inside the school, but outside, she said Me Too backlash is a concern. Rhoades admits that while the university’s Business Eagle career-acceleration program is going strong, formal female-specific mentorship is lacking. “The university has tried a little bit, but nothing sustained unfortunately.”

Not only does male management need to break up the old boys club — stop exclusively hiring young, male versions of themselves who went to the same schools — but they need to recruit through new avenues to freshen the pipeline. Then, they must ensure that those women are not passed over for growth opportunities when they finally join the team.

Qantas for example tries to incorporate diversity into its entire hiring and retention system — from top to bottom — and Southwest Airlines has prioritized hiring women as well, according to Scholnick of ICF. Scholnick herself said she never had a formal mentor, but did have encouraging bosses, for example when she worked at Hong Kong-based Metrojet.

“Oscar Muñoz has been very clear to lift up women and try to diversify in the executive offices,” said Nelson of the Association of Flight Attendants about the CEO of United Airlines, who worked to secure Jane Garvey as the carrier’s first female board chair. “He also responded immediately to our calls,” she said about her association speaking out on sexual harassment.

The Business Side Needs Youth Programs Like the Engineering Side Already Has

Airline c-suites could actually take a cue from their MRO (maintenance, repair, and overhaul) counterparts, who appear to be more proactive about speaking to young girls. There’s no conventional wisdom for the lack of women in airline c-suites according to Bloomberg, but there’s a clear explanation for the lack of women in MRO roles: Young girls have long been discouraged from entering science, technology, engineering, and math.

Many youth initiatives already exist in the more technical areas of aviation. Girls in Aviation Day is entering its fifth year, targeting girls age seven through 18, and holds events globally through chapters of Women in Aviation International. Various summer camps exist as well, including PreFlight in Texas.

The importance of familiarizing young girls with aviation is “absolutely crucial,” according to Goerner of Indiana University, not just to inspire future female pilots but to normalize the entire field. “Start getting into robotics and those sorts of third grade competitions early,” she advised.

The importance of childhood exposure to the business side of aviation was highlighted by Barry Butler, president of Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, in an essay on Runway Girl Network:

“Madison says accompanying her father on sales trips sparked an early fascination with planes and airports. By the age of 13, she was watching Shark Tank and taking notes while her friends watched Hannah Montana.”

To similar effect, JetBlue President and COO Joanna Geraghty told Skift’s Brian Sumers about coworkers recounting her success to their young daughters.

“Had I not shared that passion with my parents, I probably would not have naturally gone in that direction,” said Rolle of Western Air.

The Flybe CEO echoed the importance of family support with any STEM field. “I was lucky to have a very strict education,” said Ourmières-Widener. “[My parents] pushed me in the STEM direction.”

The carrier has a growing program for young girls called FlyShe, aimed at introducing girls to the technical aspects of aviation, but also to open their eyes to the commercial side and the possibility of executive leadership roles.

“I was a tomboy and my mother loved it,” said Ourmières-Widener, “but in some families that’s not acceptable.” When her own seven-year-old daughter asked for a Barbie like her friends had, Ourmières-Widener bought her Legos as well. “I’ve never been a fan of Barbie,” she said, citing its outdated vision of how a woman should look and act.

Rolle spearheaded an initiative called Gyal on a Mission, referencing the slang term for girl, which aims to open young girls’ eyes to all types of careers in aviation, from executives to pilots. She has also held numerous high school job fairs in the hopes of showing young women that other roles besides flight attendant and ticket taker are open to them.

Gender Parity Doesn’t Have to Wait

Some feel that change comes at a glacial pace, especially when it comes to diversity. It’s a common refrain that women must wait for the old male guard to die out, literally, before a more inclusive system can be instated. But there are real steps to be taken right now when it comes to exposure in business school, mentoring, public speaking, and diversifying the executive pipeline.

“The guys at the top have to think about gender diversity all the time,” said Scholnick of ICF. When male executives organize a dinner, promote from within, and select people for public speaking, women must be recognized for their qualifications. “They are so afraid to bring in people who are a little bit different,” she said, saying that the old boys club recruits so heavily from the same schools and channels.

Flybe’s Ourmieres-Widener doesn’t want to wait for gender parity, and doesn’t think we have to.

“If it’s a priority, you just have to deliver,” she said. “That’s it.”

The Daily Newsletter

Our daily coverage of the global travel industry. Written by editors and analysts from across Skift’s brands.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: association of flight attendants, deep dives, discrimination, flybe, gender, gender diversity, jetblue airways

Photo credit: Even in 2019, airlines have very few women in senior management positions. Skift