Skift Take

Ever since Naoshima, Japan, became home to a number of contemporary art museums, sculptures, and installations, the island's identity as an "art island" has become intertwined with its history and culture. Naoshima now represents a way for other destinations to think about how tourism, and art tourism specifically, can be used to revitalize communities while preserving tradition and demonstrating respect to heritage.

Skift Senior Research Analyst Rebecca Stone is traveling the globe over the next year as part of Remote Year, a program that brings together working professionals to travel, live, and work remotely. She'll spend a month in 12 cities around the world that include Cape Town, Lisbon, Valencia, Sofia, Hanoi, Chiang Mai, Kyoto, Kuala Lumpur, Lima, Medellin, Bogotà, and Mexico City. And every month she'll take you along for part of the journey with a feature about her observations based on firsthand reporting and data about the changing travel industry. She'll do the jet lag. All you have to do is kick back and enjoy her compelling dispatches.

When my trendy, graphic designer friend asked me if I wanted to check out Naoshima, Japan, I said “yes” without knowing where it was, what it was, or why we should go there. I’m always down for an adventure after all.

The Seto Inland Sea, also known as Setouchi, is a body of water in the southwestern half of Japan. Within this beautiful sea lies an island called Naoshima, which, up until the 1990s, no one really knew about. Nevertheless, today it’s popularly known amongst avid travelers as “the art island.”

The morning our adventure began, I woke up in Tokyo, one of the largest cities in the world as measured by population. I scrambled through Shibuya Crossing, which is one of the busiest intersections in the world, to catch an early train heading south. After three different trains, including one high-speed bullet train known as a “Shinkansen,” and a ferry ride, I found myself pulling up to a strange, dreamy island, looking part industrial, part beautifully curated, and part wistfully desolate. I wasn’t in Tokyo anymore.

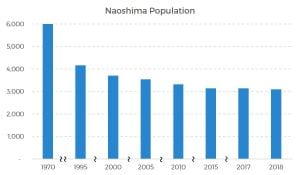

Naoshima is a 5.5 square mile island that was historically a fisherman village but is now home to a Mitsubishi smelter and refinery, the island’s primary employer, as well as numerous contemporary art installations, sculptures, and museums. As the resident population has been declining, Naoshima has seen a dramatic increase in tourism due to wealthy travelers flocking to the island to check out its world-renowned art exhibits and installations. Naoshima may have been developed into a perfectly contained and curated destination for contemporary art tourism, but the island still feels somewhat like a time capsule holding remnants of its history and culture.

Arriving at Miyanoura Port, Naoshima looks beautifully curated, rather industrial, and somewhat isolated.

Hanging out in Sou Fujimoto’s “Naoshima Pavilion” in Naoshima’s Miyanoura Port area while waiting for the bus to our guesthouse in Honmura, on the other side of the island.

Of course, Naoshima is still navigating that delicate balance of maintaining tradition versus accepting modernity. The sleepiness of its residents, cafes, restaurants, and guesthouses and the eerie quiet of the coastline at nighttime both spoke to the island’s history in a way that can really only be felt rather than explained. However, contemporary sculptures now dot the island’s hills, art houses converted from homes and buildings abandoned by local residents blend in with normal neighborhoods, and modern art museums of grey cement coexist with the land, albeit somewhat formidably.

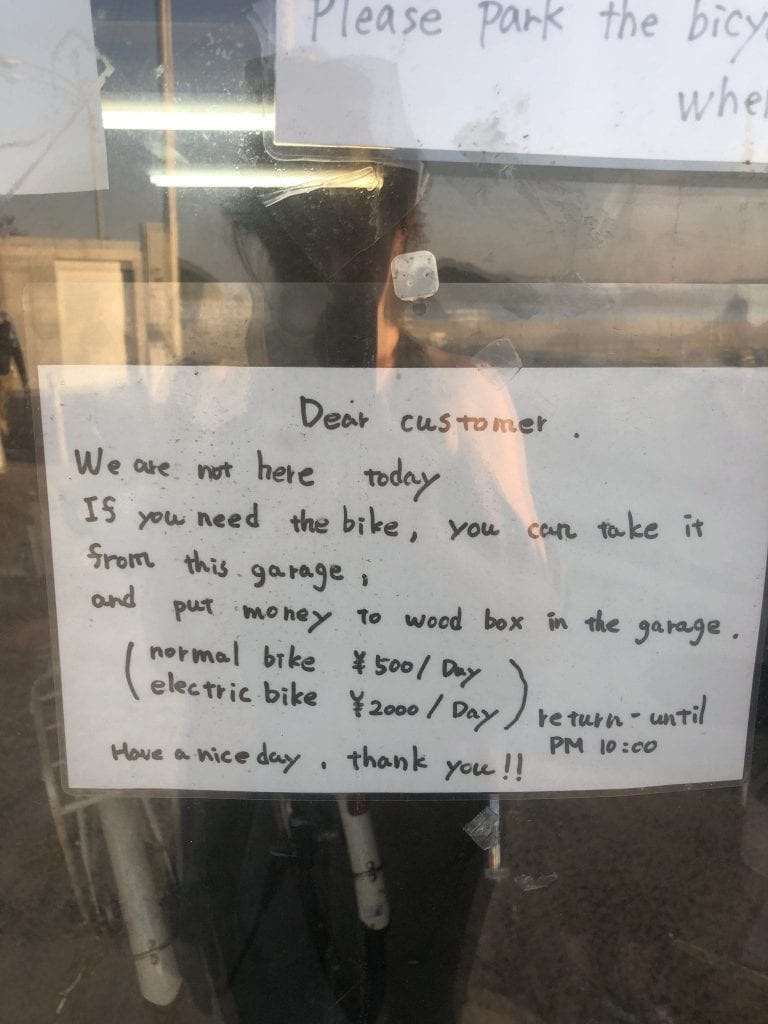

The residents of sleepy Naoshima were generally laid back and trusting. This is a sign outside a bike shop from which we rented bicycles for our stay.

Naoshima represents a way for other destinations to think about how tourism, and art tourism specifically, can be used to revitalize communities while preserving tradition and demonstrating respect to heritage. At the same time, it offers new ways to think about how to best repurpose the old with the new as well as how to create noninvasive ways for visitors to enjoy places they have never been to before. The successful development of similar areas may offer a way to reduce the overcrowding of other destinations and limit issues of seasonality.

Putting Naoshima on the Map

To give some more context on its remoteness, Naoshima is actually an archipelago of 27 islands out of the 3,000 located in the Seto Inland Sea. Three of those islands (including the main Naoshima island) have inhabitants. The main island has ebbed and flowed economically and ecologically over history as the fishing industry declined at the beginning of the 20th century and as the smeltery industry increased. Technological advances resulted in changes in types of employment and drove younger people to leave the island, which in turn caused Naoshima to face a declining, and aging, population and an unstable economy. The population of Naoshima has declined 1.4 percent on a compounded annual basis since 1970. For reference, the population for all of Japan, which has also been declining, has declined 0.4 percent on a compounded annual basis since 1970.

Source: Kondo, Junko. City Population. Chizuru Morofuji, a licensed guide at Triple Lights tours

Note: Data for all years not available.

The rebirth, so to speak, of Naoshima occurred as a result of private corporate philanthropy. Soichiro Fukutake inherited Fukutake Corporation, a Japanese education and publishing company, from his father and used his wealth and passion for art to buy a huge chunk of land on the south side of Naoshima. Fukutake, who has demonstrated views of anti-urbanism, went on to rename the family company Benesse Corporation, as Benesse is a combination of the Latin words for “well-being.” Working with famous Japanese architect Tadao Ando, the Benesse House Museum opened in 1992.

Next came the Art House Project starting in 1998, which began with the process of restoring certain abandoned or rundown houses on the island and turning them into works of art. The buildings are mixed in throughout the local community of Honmura. Some maintain the distinct architecture of the district, while others look like art exhibits themselves. In one art house, called Minamidera, which was built on the former site of a temple, one sits in a completely pitch black room. It was so dark that my friend whispered to me, “I can’t tell if my eyes are closed.” Then, a soft white light slowly appears in the distance. I couldn’t tell if I was imagining it. I’ll save the rest for when you visit.

A street located in the Honmura district of Naoshima where the Art House Project is located. Photographer: Annika Wikberg

This art house, called “Haisha,” meaning “dentist,” was the former home and office of a dentist. Photographer: Annika Wikberg

In 2004, the Chichu Art Museum opened. “Chichu” literally means “in the ground” in Japanese, and the museum is aptly named given only the entrance is above ground. The museum blends in perfectly with the earth from above, but interestingly is filled with natural light as you walk through different exhibits, which include a room containing five of Claude Monet’s Water Lilies series and James Turrell’s Open Sky, which features a square, stone room that opens up to a skylight you could gaze at for hours.

All across the island are different ways to view and experience the work of both local, Japanese artists, as well as international artists. There are museums like the Lee Ufan museum dedicated to the Korean artist, installations like American artist Teresita Fernandez’s Blind Blue Landscape, and sculptures like Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama’s Pumpkin. Some works blend in. Some stand out like a sore thumb.

Adjusting to a New Landscape

You can probably guess what the significant development of art has meant for this tiny island. Visitors went from 36,000 in 1992 when the Benesse House Museum opened, to 107,000 in 2004 when the Chichu Art Museum opened, to over 720,000 in 2016. That’s about a 13 percent compounded annual growth rate since 1992. Compare that to the 1 percent decline in the population I mentioned earlier.

Source: Survey by Kagawa Prefecture conducted by Carolin Funck in a chapter included in the book “Tourism in Transitions, Recovering Decline, Managing Change,” edited by Dieter K. Müller and Marek Więckowski. Kaida, Naoko, “Study Trip Report: Naoshima and Teshima,” 2012. Chizuru Morofuji, a licensed guide at Triple Lights tours.

Note: Data for all years not available.

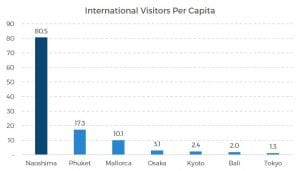

In fact, we took a look at visitors per population for a number of island destinations as well as popular Japanese cities and found that Naoshima’s ratio of visitors to resident population is astounding. We note that the other destinations use international overnight visitors, for which Naoshima had no data available. We estimated the number of international overnight visitors by assuming 40 percent of visitors are foreign (as indicated by public relations at Benesse House Museum) and that 86 percent of those visitors stayed overnight (in line with Tokyo, though this is likely overestimating the number of overnight stays given Naoshima is an island, making day trippers much more likely than in Tokyo). The point still stands: Naoshima had almost 800,000 visitors in 2016, relative to a population of 3,000 people.

Source: Mastercard’s Global Destination Cities Index. City Population. The Japan Times, Benesse House Museum.

The documentary, “Naoshima (Dream on the Tongue” (2014) by Claire Laborey, communicates how some locals feel about the development of art on their home. Toward the beginning of the film, a local says, “The island was taken over by contemporary artworks. Old houses were turned into artistic installations. Strange objects were growing along the way. An underground museum was dug into the mountain.”

“I was born on Naoshima …Today, it’s called ‘the island of art.’ For me it’s ‘the island making money with art.’”

In addition to the investment of the Benesse Corporation and corresponding art development impacting the landscape of the island and the lives of locals, the increase of tourism has resulted in the types of issues that occur in overcrowded destinations.

“The morality of the tourists is declining, not as much as is seen on the mainland [Japan], but bicycle riding is a big issue,” Matsuki Kayoko of All Japan Tours noted. “The tourists ride bicycles on the right side of the road, ride at top speeds, and stop in unnatural places to make U-turns in front of cars. It’s difficult to drive around, and although we’re grateful for the tourists to come, this is quite troubling.”

Given Naoshima is so small, riding bikes is one of the easiest ways to get around the island. My friends and I tried to be respectful and aware of Japanese road rules while riding around to various art exhibits.

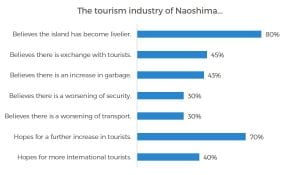

A survey of the tourism industry in Naoshima conducted by Carolin Funck in a chapter included in the book “Tourism in Transitions, Recovering Decline, Managing Change,” edited by Dieter K. Müller and Marek Więckowski, found that the overall attitude about the rise of tourism is very positive with 80 percent citing that the island is livelier as a result of tourism and that 70 percent hope for an increase in visitors.

However, there are definitely things that need to be worked on. Of the tourism businesses polled, 43 percent believe there is now too much garbage, and 30 percent believe there are issues with security and transportation. And, while they’re hoping for an increasing number of visitors, only 40 percent want those visitors to be foreigners. For reference, there were 40 valid responses in the survey, including 16 restaurants and 10 accommodations providers. 14 were located in Miyanoura, 17 in Honmura, and the rest throughout the island.

Revitalizing Communities and Creating Something New Through Art Tourism

Although there have been negative aspects resulting from art development on the island, it is now hard to separate the old from the new on Naoshima. The island’s history basically created a blank canvas for art tourism to expand. Art oxymoronically blends in and pops up everywhere. Stark, cement museums juxtapose historical homes. A normal neighborhood street becomes an art exhibit. Naoshima’s different identities all blend together.

Exploring the island was both beautiful and bittersweet. Progressive and antiquated. Serene and stimulating. Relaxing and thought provoking.

“Naoshima is a sort of border between dream and reality,” Claire Laborey’s documentary calls out.

I had never really thought about tourism specifically for art before going to Naoshima. Now I understand all of the different, innovative things that art tourism can do and how beneficial it can be to a destination. Art tourism can revitalize communities and balance tradition and modernity by maintaining cultural identities, creating jobs, engaging the local community, and finding ways for travelers to enjoy art in a noninvasive way.

Maintain Cultural Identities and Heritage

The way the Chichu Art Museum blends in with the earth and the way the art houses fit within their communities are just two ways that Naoshima has tried to maintain the original look and feel of the island.

“In the ‘Art House Project,’ a number of houses have been restored to preserve their traditional Japanese styles,” Matsuki of All Japan Tours explained. “But they aren’t out of place with the contemporary art style of the town. Although Go’o Shrine was rebuilt as contemporary art, it still reflects a taste of a Japanese shrine.” Previously abandoned and forgotten buildings are now so much more — they are beautiful, irreplaceable, and represent Japanese culture and the identity of the island.

In 1996, the focus on Naoshima shifted “toward commission-based site-specific works, and the completed pieces started to be exhibited as permanent displays inside and outside of Benesse House Museum,” according the Benesse art website. In this way, works can be created specifically for Naoshima island that don’t detract but only add to its identity. Junko Kondo, a student of the University of Jyväskylä noted in her Master’s thesis, “Revitalization of a Community: Site-Specific Art and Art Festivals, A Case of Art Site Naoshima,” that “some site-specific artworks in Naoshima are entwined with social changes, local history, identity and culture, and they seem to represent a rural life of Japan.”

The opening of the Naoshima Bath “I♥︎︎湯” (I Love YU) in 2009 is an example. Public communal bathhouses are of historical significance to Japanese culture as they represent places to gather, to share stories, to relax. The Naoshima bathhouse, designed by Japanese artist Shinro Ohtake, has artworks directly integrated into the building. In this way, people who visit can experience both art and Japanese customs. Fukutake indicated that he hoped the bathhouse would demonstrate his “feelings of gratitude to the people of Naoshima for their support of the previous various art projects executed on the island.”

In addition, the Setouchi Triennale is held every three years, with the next upcoming event in 2019. The purpose of the event, held over the course of 100 days and on 12 different islands in the region, is to celebrate the specific identity, nature, and culture of the Setouchi region through its various artworks. The 2016 event welcomed one million visitors to the area.

“The increase in art-driven tourism to the region has greatly contributed to the restoration of the Seto Inland Sea, supporting island sustainability within the Kagawa Prefecture,” said Tomohiro Muraki, director of Setouchi Tourism Authority. “We recognize that the contemporary art in the region is a key point of interest for many foreign travelers, and serves as a gateway to experiencing the culture, craftsmanship, culinary and history of the Setouchi Region. Referencing the local influences and unique character indicative to each island and prefecture, the art has lent itself to be an incredible way for visitors to learn about the distinct way of life within the region.”

Unique cultures and identities are cause for celebration, and art tourism can help travelers better understand different destinations’ heritages and histories.

Create Jobs, but More Importantly, Engage the Locals in Their Community

Carolin Funck’s work in “Tourism in Transitions, Recovering Decline, Managing Change” also discusses how the population increased from 2010 to 2015 in the Miyanoura and Honmura districts of the island as accommodations and restaurants increased. In addition, from 2005 to 2010, 30 percent of immigrants to the island were in their 20s, and another 30 percent in their 30s, demonstrating that younger people are becoming more interested in returning to Naoshima for employment opportunities and a different way of life.

The number of accommodations went from 14 to 23 from 2009 to 2012. Employees at the Benesse hotels went from 55 in 1999 to 193 in 2009.

“The art tourism market … brought money which can [help] build good infrastructure, transportation, [and add] convenience to their [locals’] daily lives,” Morofuji of Triple Lights explained. “The number of buses and ferries has increased. The café or guest house business creates employment.”

Perhaps more importantly than the economic development of destinations via employment creation, art tourism has a duty to engage the local communities themselves.

“The most successful point of this project is that Benesse’s project staff [has] tried to make the town people participate in the projects. At first, they didn’t show interest in the project which Benesse was promoting on the south area of the island,” noted Morofuji of Triple Lights. “As they participated in the event or helped the artists produce artworks, the islanders got a grasp of the project gradually. The participation of the local people can be a key point to keeping the appropriate balance between tradition and modernity.”

Kondo explains how art development has caused locals to care more about their island, become more attached to the artworks themselves as they are able to see the development process, and rediscover ordinary parts of Naoshima that they might have otherwise previously dismissed. As the number of visitors exploring the island has increased, locals have looked to take better care of their own homes and communities and become more proud of their beautiful island’s identity.

“Furthermore, I would like to believe (and propose) that the local residents in Naoshima have more than feelings of attachment and acceptance toward artworks,” She states. “I question, what if the experiencing of art is already embedded in our everyday life which intensifies joy, happiness, and all other valuable things in our life, or the art experience is something that can be learned over time, and especially when artworks exist close to living environment. In other words, so-called ‘visual literacy’ can be developed and expanded as there are various artworks exposed to the public.”

Yayoi Kusama’s “Red Pumpkin” is now part of the environment of Naoshima; a greeting upon arrival in Miyanoura. Photographer: Annika Wikberg

Provide a Way for Travelers to Enjoy Art in a Noninvasive Manner

Art tourism offers an interesting way to redistribute travelers and reduce issues of seasonality. For one, art can be enjoyed regardless of weather. I ventured to Naoshima in October — not your typical island getaway season.

The Chichu Art Museum also recently implemented an online ticketing system to control the flow of visitors. “I’ve been to the museum twice after starting this system. I can tell it is working really well,” highlighted Morofuji of Triple Lights. “The waiting times for entering the exhibition rooms of Monet or James Turrell have reduced, and the long line for entry has become shorter.”

There are also other islands in the region such as Teshima, Inujima, and Omishima that offer additional museums and art installations for travelers to experience and enjoy. Perhaps with the ongoing growth of these destinations, travelers will eventually choose to visit this beautiful region over other overcrowded destinations like Bali and Phuket, smoothing the overall number of travelers seeking island getaways in the Asia Pacific region.

Art tourism has the distinct opportunity to try to do and be something different. “One of key issues for management … [is] how they control the number of the visitors, reduce congestion, and have visitors feel [the] unique, luxurious, and enjoyable atmosphere of the island,” Morofuji of Triple Lights noted.

“The distance between artworks and spectators [is] … extremely close in Naoshima. The visitors to the island literally could spend intimate time with works of art for a whole day,” Kondo explains in her Master’s thesis. “To put it simpl[y], visiting Benesse Art Site Naoshima could not be compared with an experience of visiting a city museum. The atmosphere of an island is unique. An island tends to preserve its custom undisturbed … Surrounded by sea, the source of life in the island has been [dependent] … on nature. Time flows differently. Naoshima is small in scale but has different faces.”

“Beauty appears in the gap between what is intentional and unexpected … Beauty appears as soon as a space cut out from daily life is created.” “Naoshima (Dream on the Tongue)” (2014) by Claire Laborey; George Rickey’s “Three Squares Vertical Diagonal”

Falling in Love with Japan and Finding Restoration in the Pause

I had previously reached out to the Benesse House Museum for an interview for this article. Their public relations team got back to me, kindly denying my request. However, before he ended the email, he wanted me to know that, “From our side, we do not aspire to become a touristic destination. We focus on the revitalization of the islands of the Seto Inland Sea through art, and hope to provide environments and opportunities for each visitor to pause and think about modern society and what true well-being (i.e. “Benesse”) might be.”

Up until my visit to Naoshima, my time in Japan had been somewhat challenging. There was more culture shock than I realized — my loud voice and relatively laid back attitude made me consistently feel like I was disturbing the peace. This is coming from a Type-A, rule-following, personality, too.

As I took the ferry back to the Uno, the town on the mainland from which I would take four trains to get back to Kyoto where I was based (perhaps all along, part of Naoshima’s allure is its remoteness), I found myself in awe of the beauty of Japan. And not just its nature, its water, and its mountains.

I thought about my friends and I sitting barefoot and cross-legged around a tiny table at a restaurant in the Honmura district of Naoshima at dinner one night enjoying grilled octopus and rice with raw egg. I thought about how the manager of our guesthouse walked me all the way to the bus stop to make sure I didn’t get lost. I wondered how many times I had bowed and would bow to people during my time in Japan in order to show respect. I thought about the vivid, completely unique experiences I had with art during my time in Naoshima that were different than anything I had ever experienced before.

I had fallen in love with the art and finesse of Japan — the delicacy of its practices, the kindness of its people. I found respect in the simplicity of lines, of light, of soft smiles. I felt revitalized in the assessment of true well-being. I found restoration in the pause.

“In front of each work , I ask myself: ‘what is it?’ But it doesn’t keep me from feeling something.” “Naoshima (Dream on the Tongue)” (2014) by Claire Laborey; Yayoi Kusama’s “Pumpkin”

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story misstated that there were three of Claude Monet’s Water Lilies series at the Chichu Art Museum instead of five; that Yayoi Kusama’s yellow pumpkin sculpture is called Yellow Pumpkin. It’s officially called Pumpkin. The story also misstated that the ratio of foreign visitors is approximately 70 percent when it is 40 percent, according to information provided by public relations at Benesse House Museum.

The Daily Newsletter

Our daily coverage of the global travel industry. Written by editors and analysts from across Skift’s brands.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: climate change, data and discovery, destinations, japan, skift on the road, skift research, sustainability, tokyo, tourism

Photo credit: One of the most famous sculptures on Naoshima Island, Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama’s "Pumpkin," stands alone in twilight. Skift