Skift Take

The direct booking wars will not be fought by laying out the evidence to parliamentary committees, but in the hearts of consumers. Still, the arguments and the evidence are definitely worth reading

The conflict between hospitality brands and the online travel agencies that sell their products is in full bloom as we head into the summer of 2016, and it will only get more ferocious as the year progresses.

We said as much in our 2016 Megatrends Forecast magazine earlier this year.

Now a European Union Committee has come out with lengthy report on what it calls “Online Platforms and the Digital Single Market“, which includes detailed testimonies by various online and digital players across Europe on the pros and cons of going single market for digital businesses across the European Union countries. The report is the end of an “investigation” (read: testimonies) on how the largest online platforms use their market power and whether the current regulatory environment remains “fit for purpose.”

As part of that, online travel was a key part of this process, and players like Airbnb, TripAdvisor, Skyscanner, and British Hospitality Association also testified. One testimony particularly caught our eye: an anonymous testimony, very likely from a hotelier that has business in Europe, on the complaints it has against the big OTAs and online travel players, particularly Priceline Group, Expedia and TripAdvisor.

The anonymous declaration accused online travel agencies of adjusting prices based upon users’ browsing histories, among other things. As any follower of Google or Microsoft’s troubles in Europe would recognize, some of the complaints focused on parts of OTA’s businesses that were a direct result of their success at being good at what they do, as opposed to a grand conspiracy. But it also focused on elements of their business that have long bothered hotel chains, hotel operators, airlines, and others.

It is an engrossing read, primarily because in a series of 16 questions and considerations, it lays out a litany of complaints of the detrimental effects (from a European perspective) of too much concentration of power in the hand of online travel booking players. Also, we’re slightly biased because it mentions one of our previous stories as evidence as well.

We are extracting that anonymous testimony in full. Pour a cup of coffee (or tea) and dive in!

Summary and Key Asks:

The growth of online platforms, which are now at the heart of modern commerce, should be examined carefully. While they can bring benefits, there are also pitfalls to the emergence of online platforms. Online platforms can rapidly scale. They tend to have small payrolls and are often less capital intensive than the business that they intermediate – allowing them to achieve significant market power in short periods of time. A concentration of market power is rarely beneficial for consumers. It can also create a perverse situation where the business of providing a good or service is significantly less profitable than the business intermediating its sale.

This submission illustrates the consumer detriment currently being created by Online Travel Agents (OTAs), amongst the largest and most profitable of all online platforms. The market is dominated by a small number of OTAs which are using their market share to charge unfairly high rates of commission from hotels, and to introduce one-sided agreements (most-favoured nation and rate parity clauses) which prevent hotels from charging less when selling directly to consumers. This means that hotel guests are paying more for their room regardless of whether they use the online platform or not.

Several European member states, as well as enquiries into other sectors, have shown that there are simple steps that can be taken to improve transparency and re-balance the online hotel booking marketplace:

- Stop uncompetitive practices: The most effective action to create more price competition would be a ban on anti-competitive most-favoured nation and rate/condition parity clauses across Europe. This simple move would free all market participants to compete on price and quality, not simply through one-sided imposition of restrictive contract terms.

- Shine a spotlight on unfair and misleading commercial practices: OTAs are currently engaging in numerous practices such as advertising false discounts, search results which are distorted by commercial factors rather than the best deal for the customer, and hidden commission arrangements. Customers are not aware for example that a service that appears free in fact carries a hidden commission charge of somewhere between 15 and 30 per cent. We believe that it is appropriate to demand transparency from OTAs, asking them to explain clearly to the customers on their websites how their businesses really work.

- Search transparency: The basis for search rankings must be clearly presented. Customers should be clear when hotels are being promoted up search rankings because higher commissions are being paid, or to other non-price factors.

Defining Online Platforms

1. Do you agree with the Commission’s definition of online platforms? What are the key common features of online platforms and how they operate? What are the main types of online platform? Are there significant differences between them?

We agree with the Commission’s definition of online platforms. The Commission correctly recognises that they provide a wide range of services and adopt a range of business models. Our response focuses on the role of platforms within the online hotel booking sector.

There are primarily three different types of platform operating in this market, working in increasingly interdependent ways:

- Search engines (e.g. Google): These effectively act as the gateway to customer interactions on the web. The first step in many online hotel booking journeys is a web search for a term such as ‘hotels in Bournemouth’. This will return adverts paid for by other platforms and hotels, results returned by Google Hotels, Google’s new accommodation platform, and some organic search results ‘below the fold’. Search engine revenues come from advertising charged in relation to the positions companies want to achieve on the search engine results page (SERP). Increasingly Google is promoting its own ‘instant bookings’ service which is commission-driven and is akin to Google becoming at online travel agent (OTA) – please see below.

- Online travel agents (OTAs) (e.g. Expedia or Booking.com): These platforms allow customers to search for hotels, compare prices and then make a booking through their sites with the hotel providing the room. These sites set up contracts with hotels and B&Bs to secure inventory to do this.

OTA revenues come from the commissions hotels are charged for the bookings they intermediate. Whilst these used to be around 10 per cent, commission rates have increased dramatically over the last ten years.

Commissions charged by OTAs are typically 15-30 per cent of the value of the stay, although there is anecdotal evidence that they are sometimes even higher than this. In the UK commissions are generally paid on the VAT inclusive rate so the actual commission costs to hotels are closer to 18-36 per cent. Booking.com further supplements these commissions by asking hotels to pay for preferential placing – typically a further 3 per cent.

OTAs spend a large proportion of the commissions that they collect on metasearch where they bid against the hotels that pay them the commission. - Metasearch platforms (e.g. Trivago and Tripadvisor): These platforms compare prices offered across different OTAs and hotels. Metasearch firms make money through selling advertising on their searches like search engines. But rather than commissions, they charge a cost per click as well as for standard advertising. It is worth noting that two of the largest metasearch providers, Trivago and Kayak, are owned by the two large OTAs, Expedia and Priceline/ Booking.com respectively. Recently, certain metasearch players have moved into the booking space themselves – either through contracting with hotels for inventory or obtaining it through third party sellers. Notably, Tripadvisor has signed a deal with Booking.com to allow customers to book rooms directly on the Tripadvisor site.

Each of these models is different, but they share problems which we think regulators and consumers should be aware of. These relate to a lack of transparency, practices associated with their strong market position and consumer deception. We will elaborate on these further in our response.

2. How and to what extent do online platforms shape and control the online environment and the experience of those using them?

Platforms have a profound effect on the online experience. They act as gateways to other websites and apps, as intermediaries and as sellers of services. This places them at the heart of the huge numbers of transactions undertaken online. The implications of this for UK consumers are particularly pronounced because British consumers buy more online than other Europeans.

The market for leisure and business accommodation is no exception. Research by Nielsen shows that hotels are one of the top three most popular items British people plan to buy online[1], while according to the ONS, nearly 40 per cent of adults made travel arrangements online in 2014.[2] In July 2015, in the UK alone, Expedia, Tripadvisor and Priceline sites like booking.com were visited 144 million times.

Given OTAs only entered the market in the early 2000s, this represents a staggering transformation in the way hotel accommodation is sold and bought. Rapid growth and consolidation has allowed OTAs to develop considerable influence over all online sales through their very large marketing budgets. The Priceline Group (booking.com) is reported to be the biggest spender on Google AdWords, with a spend of nearly $1.8 billion in 2014[3]. By dominating in paid search, OTAs have increasingly become a ‘toll booth’ on internet sales of accommodation. This is borne out by a survey we conducted of UK hotels where 87 per cent stated they would prefer to use OTAs on an as-needed basis, but are compelled to use them if they are not be shut out of the online channel and from there the web.

Control of the Online Environment: How Search Results are Determined

One area of particular concern to us is the way that OTAs present search results. When a survey asked customers why they use OTAs, 82 per cent said it was ‘to get the lowest price’. From a consumer perspective, then, the OTA is doing its job if it helps guide them to the lowest price for a given location and class of hotel.

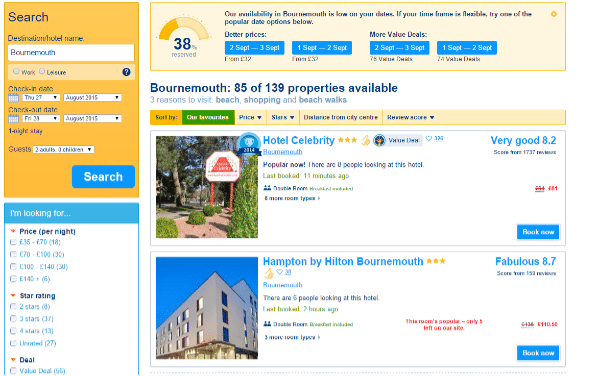

Because consumers do not look far beyond the first few search results, featuring high up in default search results is vital for a hotel to secure click-through sales.[4] Therefore it is important to note that OTAs do not sort hotel search results by price by default.

By default this booking.com shows ‘Our favourites’, not lowest price. Expedia shows ‘Recommended’ properties. The reason a hotel is displayed at the top of this list is not made clear and is an opaque mix of the commercial factors outlined above.

In fact, the top results are those ‘recommended’ by the OTA. The basis of this recommendation is opaque and is comprised of the following factors:

- Price: OTAs gain a percentage of the total booking from their commission rather than a flat fee as in the airline model. It is therefore in their interest to promote higher cost hotels, on which – all being equal – the most commission will be paid.

- Level of commission paid by the hotel to the site: hotels are told the more commission they pay, the higher they will appear in the sort results

- Conversion: The conversion ratio (i.e. the ratio of views to sales) that a given hotel achieves through the OTA (establishments fall in the sort order if people view the hotel listing but don’t subsequently purchase).

- ‘Competitive’ rates: Rather than some measure of value for money for the consumer, having competitive rates means that the accommodation provider agrees to provide the OTA with the same price for a room as they would to a customer booking directly with them through their website or calling the property directly. This is known as a ‘rate parity’ or ‘most-favoured nation’ clause and is typically forced on hotels in spite of the OTA’s high cost of sale.

Individual hotels are routinely threatened by OTAs if they attempt to offer the consumer a lower price through their direct channels (even when they have been permitted to do so to ‘closed user groups (CUGs) through national competition authorities’ commitments processes). 40 per cent of UK hotels surveyed reported they had been threatened in this way by a platform. This is rarely done in writing as the powerful OTAs can take unilateral action to punish hotels (such as by suppressing them from appearing on their websites).

What actually determines the sort order the customer sees (or even whether a hotel is displayed at all) is entirely shaped by commercial factors which, in apparent infringement of the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive, is not made clear to the consumer.

It is important to note that we know a consumer will rarely alter the default search on a website (ie. from the ‘our favourites’ or ‘recommended’ option). It would be more transparent for the OTA to display hotels in a list based on distance from the location the customer is looking for, or price – more objective factors that would actually help the user make an informed choice.

3. What benefits have online platforms brought consumers and businesses that rely on platforms to sell their goods and services, as well as the wider economy?

Businesses that rely on platforms: For businesses such as hotels (especially the smallest, which do not have large marketing budgets), it is argued that platforms can offer a route to a market that was not previously open to them. The platform can connect them to potential customers all over the world. Hotels now report[5] that the existence of such large players act as a disincentive for them to innovate to reach customers as their marketing budgets cannot compete:

‘The sheer size of the challenge would mean I would need to spend a budget too large to try and compete’

‘It is difficult to compete with the online presence of Booking.com’

‘OTAs are heavily impacting our bottom line so we have less money to play around with [for marketing activity]’

‘High commissions mean that marketing activity has to be curtailed’

OTAs have also worked out ways to restrict hotels’ ability to contact guests directly such as not providing the email address of the guest or not informing the hotel about the purpose of their trip. This makes it harder for the hotel to cater for guests’ needs and removes the ability of the hotel to create a direct relationship with the guest it is looking after.

Consumer benefits: The benefits for consumers of platforms, including OTAs, are widely held to be the convenience, choice and price comparison functionality they offer.

While we think there is a place for platforms in the market and that they can offer customers benefits, those benefits would be greater if they allowed consumers to make an informed choice. They could inform customers by being transparent about the way the search sort order is determined and how they make their money. UK consumers would also benefit if the insistence on rate parity was banned as it has been in France and Germany (and expected in Italy), thereby allowing hotels to use the powerful middle man where it provides value to the guest and the hotel and pass the benefits on to the guest.

4. What problems, if any, do online platforms cause for you or others, and how can these be addressed? If you wish to describe a particular experience, please do so here.

Just as in the offline world, intermediation by platforms can bring significant problems, particularly when those intermediaries have enough market power to engage in behaviours which undermine the interests of customers and their suppliers. These issues have been explored by two recent academic papers which find that, contrary to claims by platforms, online intermediation can drive up prices for all consumers, whether they buy direct from a supplier or via an intermediary.[6] We explore some of these problems further below.

Market Concentration

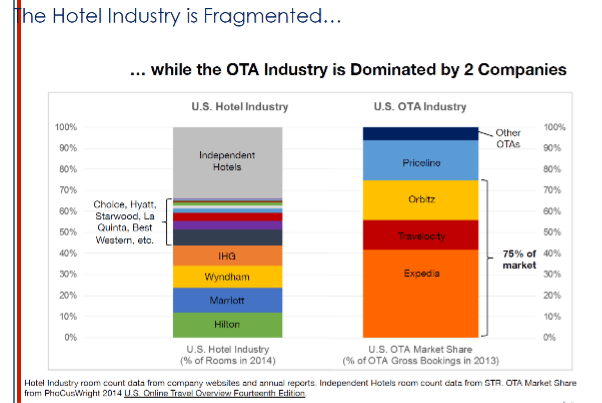

Concentration of OTA market power is of increasing concern. Booking.com had a market share of 39 per cent in 2013, which has since grown further still and now is believed to be between 60 and 70 per cent. Expedia and Hotels.com (an Expedia company) hold much of the remaining share of the online market. Forecasts show that the Priceline Group (which owns Booking.com) and its competitor Expedia will control 94 per cent of all online hotel bookings by 2020.[7]

This concentration contrasts sharply to the diversity found in the hotel business: in Europe, 60 per cent of hotels are independent and only 16 per cent of rooms belong to the top five hotel companies.[8] Even the world’s largest hotel companies have less than 1 per cent of the inventory displayed on the leading OTA sites. This gives OTAs huge control over the marketing and online sales of hotels, and in their bargaining power with their ‘suppliers’. If hotels – particularly small independent hotels – do not take the terms dictated by the OTAs they are effectively closed out of the online market. If left unchecked, this will lead to an increasingly dysfunctional market for both visitor accommodation providers and consumers. This dysfunction is manifested in several ways:

- The existence of rate-parity clauses in contracts between hotels and OTAs: Due to the power OTAs have in the online market, they typically insist on a clause in their contract with hotels saying that they cannot offer a lower price direct. OTAs want to prevent hotels from marketing any rate which is cheaper than the one that appears on their website – it becomes a ‘walk away’ point in contract negotiations with them and we have countless examples of threats made to hotels in this regard. This has the perverse impact that hotels cannot offer a lower price direct to the consumer, even though when selling direct they don’t have to pay a significant commission to the OTA. This frustrates genuine price competition. While these clauses have been banned in France and Germany, they persist in other countries including the UK.

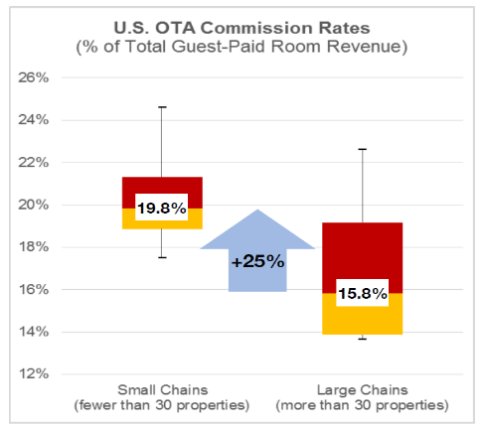

- The high level of concentration of market power in the hands of OTAs has driven up the commissions that they charge. When OTAs entered the market, commissions were typically around 5 per cent. They are now in the range of 15-30 per cent. Research from the U.S. shows that hotel companies with less than 50 properties pay even higher levels of commission[9].

- There is also increasing evidence that this is driving up prices for customers whether they book their travel online or offline.[10] In their study, Associate Professor Ben Edelman, Harvard Business School and Julian Wright, Professor, National University of Singapore find the following:

‘Price coherence[11] operates by making all buyers share the intermediary’s fees to sellers, thereby raising the price of direct purchases. This increases demand for the intermediary’s service, allowing it to charge more and increasing its profit. This mechanism operates through three related channels. First, when an intermediary charges sellers positive fees for intermediated transactions, price coherence results in all buyers sharing these fees through higher retail prices. This makes direct purchase (or purchase through another intermediary) more expensive, which increases the number of buyers joining and using the intermediary. Second, with price coherence in place, an intermediary does not face a reduction in demand when it raises seller fees, provided that sellers continue to participate. Finally, an intermediary can provide rebates or other benefits to buyers and correspondingly increase its fees to sellers, which further raises the cost of direct purchase and the benefits of intermediated purchases, thereby attracting even more buyers to join while ensuring that sellers remain willing to join.’ - At the same time, customers are unaware how much of the cost of their booking is swallowed up by just a few minutes browsing on an OTA website.

- Other sectors have also recognised the market damage created by price comparison websites (PCWs). In the energy sector, the collective energy switching website, The Big Deal, has accused the market leading PCWs of posing as consumer champions, whereas in actual fact they ultimately do not have the consumers’ interest at heart. The Big Deal said PCWs were not capable of providing “honest advice” due to their funding structure.

5. In addition to concerns for consumers and businesses, do online platforms raise wider social and political concerns?

Platforms raise a wide range of social questions, including:

- Data protection: How user data is used and the extent to which privacy is protected.

- Tax collection: Certain platforms only pay VAT on the rate they charge the consumer, that is the rate exclusive of their commission. If this booking was made directly with the hotel, or if OTAs paid VAT on the total the consumer actually pays the amount raised for the exchequer would be higher.

- Implications for employment: Typically platforms have very few employees, whereas the business they are displacing tend to be more labour intensive. Tourism and hospitality is responsible for nearly 10 per cent of employment in the UK.

- Treatment of small business suppliers: As mentioned, smaller businesses are less able to negotiate with powerful platforms and will sign up to unfavourable contract terms because of OTA market power. These conditions include rate parity clauses as discussed, last room availability clauses (where a platform demands access to inventory even when the establishment would be able to sell rooms on its own – in peak periods for example), difficult cancellation conditions and refusal by platforms to supply customer data (to prevent the hotel or B&B contacting the customer separately at the risk an OTA is not used for the next booking). These measures mean operating a small business in our sector is rarely profitable. Banks are increasingly refusing funding to hotels that don’t work with the larger brands because of the lack of profitability in the sector.

Platforms as Part of the Digital Single Market Strategy

6. Is the European Commission right to be concerned about online platforms? Will other initiatives in the Digital Single Market Strategy have a positive or negative impact on online platforms?

The Commission is right to be concerned. Platforms have become such a significant part of modern commerce and their positions are so powerful vis-a-vis the suppliers they work with that there should be a review of their practices and an attempt to bring more transparency for consumers to help them make an informed choice. This is important for the sustainability of one of Europe’s key industries and to ensure that consumers are not being misled.

In response to the second part of the question, the assessment of online platforms is the main way in which the Commission will assess platforms and their interaction with suppliers and consumers. However, the Digital Single Market strategy has implications for a number of initiatives that pre-date the launch of the strategy. This includes the competition investigation into Google. As explained in our response to Question 1, Google plays an active role in channelling customer searches towards paid adverts and Google’s own shopping service. It is possible that the competition investigation into Google Shopping, which is a separate initiative but should not be seen in isolation from the DSM, could have a bearing on its hotel booking platform.

The Commission is also in the process of modernising the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive to ensure that it remains relevant as an increasing proportion of purchases take place online. As is explained in more detail in our answer to Question 16, it is anticipated that the accompanying guidance to the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive will be updated to increase the transparency of common practices used by online travel agents. This could include making clear in the guidance that the criteria for determining search results and the use of commissions must be prominently displayed. Once again, this initiative pre-dates the DSM but shares a common objective with the strategy.

7. Is there evidence that some online platforms have excessive market power? Do they abuse this power? If so, how does this happen and how does it affect you or others?

We have outlined many of our concerns in relation to this question in our answer to Question 4. Our primary concerns are about the use of anti-competitive rate parity clauses and the existence of excessive commissions (and the systematic misleading of consumers through misleading advertising). Public policymakers are increasingly recognising that a problem may exist and are taking action:

- The Italian Parliament voted 434:4 against rate parity clauses in OTA contracts with hotels.

- France has outlawed rate parity clauses in the hotel sector as part of the Loi Macron.

- A German judge banned the (at time of investigation) leading German OTA from using them, saying that their impact on competition is ‘massive’.

- The Swedish Competition Authority closed its investigation into Expedia due to the company voluntarily changing its contract commitments with hotels in a similar way to Booking.com – Expedia can no longer stop hotels from offering other OTAs the same price or a lower one than they are offered. (We believe this will not solve the issue however).

While this is encouraging, a patchwork of different rules is emerging. Last year the UK Competition and Markets Authority banned ‘wide MFN’ clauses in the market for car insurance. This stops price comparison websites (PCWs) and car insurers from signing exclusive deals to offer lower prices. This was an effort to ensure there is greater competition between PCWs. While this is a step forward, we do not believe this approach solves the underlying problem as PCWs can still stipulate that the provider is not allowed to undercut them in the direct channel. If both leading OTAs continue to have a rate parity agreement with the hotels they work with, competition between OTAs will necessarily be non-existent, even if in theory they ‘allow’ for this to happen by telling the hotel they can offer a lower rate to other OTAs.

The UK CMA has closed its own investigation into hotel bookings, saying that it will monitor activity for the next twelve months and await further European developments.

Consumers Have a Perception of Choice, Where There Is Actually Little

Consumers may believe there are a large number of OTAs in existence but in fact many belong to two powerful players, Expedia and The Priceline Group. In turn, these large companies also own metasearch sites such asTrivago and Kayak. Through organic growth and acquisitions, these companies have become Wall Street giants. Priceline Group, the world’s largest OTA group has a market capitalisation of nearly $70 billion – greater than the four largest hotel companies combined.

The OTA market is highly concentrated. Many well-known brands are actually owned by just two companies. It’s expected that Priceline Group and Expedia will control 94 per cent of all online hotel bookings by 2020 (Source: submitting company’s data and market projections). They have hundreds of affiliate sites also creating the impression there is a lot of choice in the market.

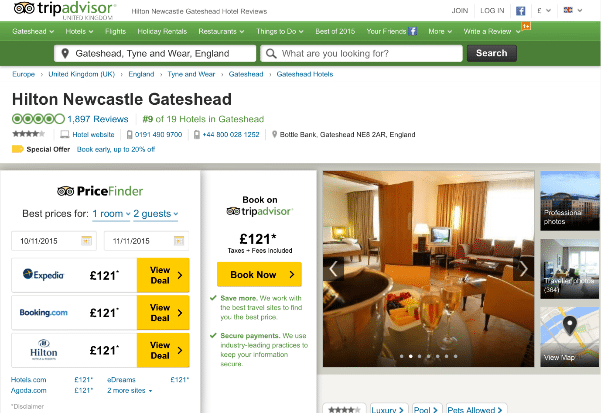

Until recently, leading OTAs insisted on parity between each other – meaning that the largest OTAs wanted to ensure a hotel does not offer a lower price to a competitor. While in accordance with recent competition authority investigations, leading OTAs have given up this contractual clause, in practice consumers are still not being presented with lower prices as you can see from the illustration below:

These images from a real search illustrate a rate-parity clause in action, with the same price being set across different sites.

Unilateral Contract Alterations

The standard terms and conditions of the large OTAs allow them to make unilateral amendments to their contracts. This is not something that one would typically see in a balanced relationship and shows the immense market power and indispensability of the large OTAs. Usually a contract is a bilateral agreement that would take both parties to such agreement to agree on any further changes rather than giving one party free hand to dictate terms.

An example of the way that this power is used was seen this summer. Following investigations by various national competition authorities into the use of most favoured nation clauses by OTAs, Booking.com proposed a series of commitments that they claimed would lead to more price competition, but which actually prevent hotel companies from offering customers cheaper prices as they are restricted from undercutting Booking.com. Following the acceptance of these commitments by regulators in only three countries (two of which have since been effectively overruled by their own legislatures), the two large OTAs (Expedia and Booking.com) informed hotels about changes to their contracts through email notification with very limited notice periods (four days) to understand and accept the changes. In the case of Booking.com, these changes were not agreed with hotels beforehand and introduced new terms that went beyond what was agreed during the commitments process.

Unilaterally changing a contract is not only poor business practice, it also demonstrates the power of these companies in relation to the small hotels they work with. Furthermore, the fact that the two market leaders sent similar emails to all hotels in Europe within three days of one another, setting out extremely similar conditions, is indicative of the level of synchronicity between the two large players.

Two Large Players – Co-operation

The Priceline Group accounts for 60 per cent of all OTA bookings in Europe, whereas Expedia has 75 per cent of the market in the US through its Orbitz acquisition[12]. The chart below illustrates the US situation compared to the relative fragmentation of the hotel market. The US hotel market is actually more concentrated than in Europe where branded hotels account for only 16 per cent of the market.

As described above the two large OTAs in this market follow one another in terms of their interactions with suppliers. Routinely, when one OTA makes a change to conditions the other will immediately follow suit. It is not in their interest to compete given their market power in two different markets.

The two leading OTAs are also a key source of advertising revenue for one another given the volume of advertising they place on each others’ respective metasearch sites – Kayak and Trivago[13].

8. Online platforms often provide free services to consumers, operate in two- or multisided markets, and can operate in many different markets and across geographic borders. Is European competition law able adequately to address abuse by online platforms? What changes, if any, are required?

As mentioned in our answer to question 7, there have been recent decisions in France, Italy and Germany to outlaw parity clauses in contracts between hotels and OTAs. Sweden and Ireland maintain them but have banned parity clauses between OTAs. Other countries are waiting to decide based on the impact of these new rulings, but a veritable patchwork of different approaches is emerging.

With tourism being the third-largest industry sector in Europe and bookings made across border every second, it is important to have to a well-functioning integrated, single market. We would advocate a Europe-wide ban of parity clauses. This would increase competition between OTAs and the direct channel and ultimately drive down prices for consumers.

9. What role do data play in the business model of online platforms? How are data gathered, stored and used by online platforms and what control and access do consumers have to data concerning them?

We do not have the information to answer this question.

10. Is consumer and government understanding and oversight of the collection and use of data by online platforms sufficient? If not, why not? Will the proposed General Data Protection Regulation adequately address these concerns? Are further changes required and what should they be?

We do not have the information to answer this question.

11. Should online platforms have to explain the inferences of their data-driven algorithms, and should they be made accountable for them? If so, how?

We have outlined our concerns with the presentation of search results in our answer to Question 2. In addition, OTAs provide other information that can be used to inform consumer decision making. Typically this is in the form of star ratings, customer reviews and popularity of the hotel with other customers. The CMA says that reviews informed up to £14.4bn of purchases in the travel and hotels sector. Reviews can be helpful to customers and help them make better decisions so long as they are fairly presented. Similarly it is important that the basis for star ratings given are transparent. Too often the reasons for a given rating are opaque and potentially open to manipulation.

12. Can you describe the challenges that the collaborative economy brings? What possible solutions, regulatory or otherwise, do you propose? The current regulatory environment and possible interventions

Enforcement of health and safety legislation which applies to accommodation provided through sharing economy platforms needs to begin. Currently no premises rented out to visitors are checked or risk-assessed even though they clearly fall under the scope of the fire safety guidelines (see the guide: Are you taking paying guests?[14]).

13. How are online platforms regulated at present? What are the main barriers to their growth in the UK and EU, compared to other countries?

OTAs are relatively lightly regulated. We would like to see more consistent application of consumer protection rules in the online market and a thorough review of their market power. We develop this further in our answer to question 16.

14. Should online platforms be more transparent about how they work? If so, how?

We believe that online platforms should be more transparent in two key areas. First, OTAs are not open about the source of their revenues. Customers are unaware that what appears to be a free, unbiased service actually carries a high price tag. We believe customers would be surprised to see how much of the cost of their stay is accounted for by commissions.

Whilst commission for price comparison sites in other sectors usually amounts to a few pounds, independent hotels pay up to 30 per cent of the entire value of a booking to OTAs (i.e. not just a cost per transaction). Even the largest hotel groups pay around 20 per cent in commission. For a week at a hotel charging £150/night a guest would be alarmed to discover pay £210 to the price comparison site for the few minutes they spent on the site to identify the accommodation. As price is key indicator of quality, without this information the consumer is also being misled as to the quality of the hotel room they are booking.

We believe, therefore, that consumers are not currently able to make fully informed purchasing decisions as they are not aware where their money is going. OTAs should clearly demonstrate on their website their commission structures and the nature of their relationships with suppliers.

Secondly, as we indicated in our answer to question 11, we have concerns about the way that search results are presented. Consumers use OTAs because they think they are seeing the whole of the market at the lowest price in one place. However, OTAs only show hotels contracted to them so they do not show the whole of market. Customers are typically not aware of this. Furthermore, because hotels can jump up the rankings by paying extra commissions, it should be clearly signposted on OTA websites how search results have been ranked and whether ‘recommendations’ are based on a higher commission paid by the hotel rather than more objective criteria based on what a customer might be looking for – quality/price etc.

There was a similar issue with energy price comparison websites which led to Ofgem, the industry regulator, setting a requirement for accredited sites to meet tighter standards on how tariffs are displayed. This is so consumers can be confident that deals aren’t hidden from view. Sites also have to list prominently which energy companies they have commission arrangements with, and make it clear that they earn commission on certain tariffs. We support a similar code for OTAs in our sector which show when commission has been paid to alter OTAs’ search results.

15. What regulatory changes, if any, do you suggest in relation to online platforms? Why are they required and how would they work in practice? What would be the risks and benefits of these changes? Would the changes apply equally to all online platforms, regardless of type or size?

We advocate the banning of anti-competitive most-favoured nation/rate parity clauses. Currently, OTAs say they drive lower prices through these clauses but we believe they may be having the opposite effect by preventing price competition in other channels and increasing pricing across all channels.

As seen in other EU member states, the banning of rate parity clauses is straightforward to introduce as it simply removes the ability of OTAs to contractually bind hotels to a minimum room price. There is a risk that regardless of the legality, platforms will simply threaten to drop hotels and B&Bs in their rankings (or altogether) if they don’t offer ‘competitive rates’.

However, we feel that banning parity clauses would give a fragmented industry the legal backing and justification to determine its own pricing, allowing it to undercut OTAs in the direct channel and to allow more robust competition between OTAs to the benefit of consumers.

We also recommend the introduction of rules which demand transparency on commission levels and a clear indication when commercial transactions (such as higher commission payments) are used as a basis from promoting (or suppressing) hotels in search results.

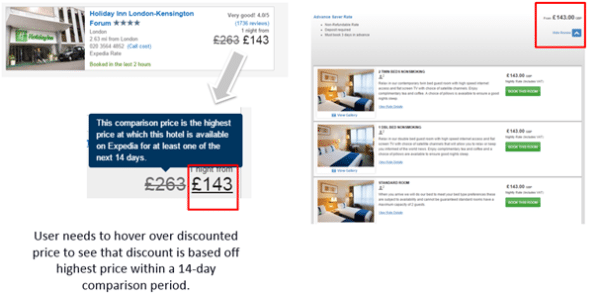

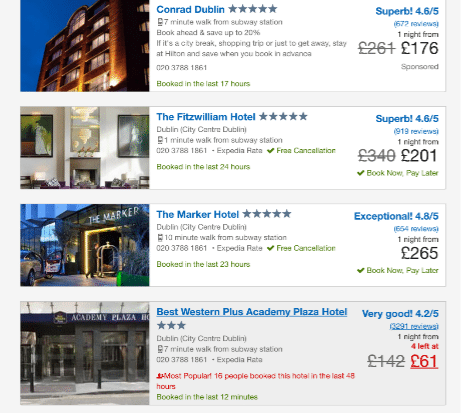

Lastly, we have discovered that OTAs frequently tell customers that they are receiving a discount when it is not actually the case. One method for doing this is to compare the cost of the requested dates with the cost of dates across a 14/30 day period on either side of the search and show a ‘discount’ calculated against very highest price available in that range. Therefore, if you request the cost of a room on a Tuesday, you could be shown a ‘discounted’ price which is simply the difference between the actual cost and what that room would cost on the most expensive day that month. This is not a discount in any meaningful sense.

OTAs purport to provide a discount, when in fact they are comparing the hotel’s actual price for that night and a more expensive one, and pretending the price difference a discount. Rate parity clauses mean these discounts are necessarily fictitious.

Trivago creating an illusion of a discount with Booking.com by comparing to highest rate listed (by another OTA – in this case ‘SuperBreak’). The £47 ‘saving’ is not actual because it does not relate to the initial seller’s offering.

The fact that OTAs are agents – that also insist on rate parity with hotels – means that any discount they offer is logically impossible.

The practices identified above appear to represent infringements of the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (which states that ‘material information’ should be provided to the consumer to allow them to make an informed decision. The responsible Commissioner, Vera Jourava has indicated that this should include commercial relationships determining sort order of results and advertising). The Directorate-General Justice within the European Commission is currently reviewing the Directive and its accompanying Guidance document with one objective being to make its application in how it relates to price comparison websites clearer. There is concern that current enforcement is not sufficient among Member States.

16. Are these issues best dealt with at EU or member state level?

The ultimate objective should be to create a level-playing field across the entire EU. Therefore, to ensure that standards are consistent and centrally applied, we believe that these issues, which are an EU-wide problem, should be dealt with at the EU-level.

In December, the EU will publish principles which clarify the applicability of the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (UCPD) to the current practices of OTAs. The UCPD was adopted in 2005 and transposed into UK law in 2008 through the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations and Business Protection from Misleading Marketing Regulation. The UCPD covers misleading actions and misleading omissions, both of which appear to be relevant to OTAs.

Once these principles are published, we are looking to the British Government, and other EU member states, to hold OTAs to account for the common practice of providing a seemingly impartial recommendation, which is in fact linked to levels of commission; failing to disclose the link between commissions and the position in the search rankings; claiming to offer substantial discounts and other practices in infringement of the the UCPD.

The European Commission is also well-placed to lead in this area given its decision to conduct a formal review of the UCPD under the Better Regulation agenda, which aims to improve and modernise existing legislation. The purpose of the review is to improve the framework for online purchases. Given that price comparison sites were highlighted in 2013 as an area where law was not being enforced and the Commissioner Jourova has recently called for more transparency in this area (see European Parliament Written Question E-002548-15), it is likely that the review will examine if the rules need to be tailored to explicitly cover price comparison sites.

Notes:

[1] http://www.marketingmagazine.co.uk/article/1314206/british-consumers-buy-online-europeans

[2] ONS: Internet Access – Households and Individuals 2014

[3] http://skift.com/2014/05/21/priceline-and-expedia-are-googles-two-most-important-advertisers/

[5] Survey conducted by author of this submission, 2015

[6] Benjamin Edelman and Julian Wright, “Price Coherence and Excessive Intermediation”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics (2015), Volume 130 (3) and David Ronayne, Warwick Economic Research Paper No 1056 (revised June 2015)

[7] Redburn Fundamental Research/ Travel and Leisure/ 2 March 2015

[8] Source: Phocuswright European Travel Overview, December 2013

[9] Data shown in accompanying graph is aggregated industry data from Kalibri Labs, LLC 2015

[10] Benjamin Edelman and Julian Wright, “Price Coherence and Excessive Intermediation” (see footnote 6)

[11] Price coherence, according to the article is where an intermediary (e.g. an OTA) contractually constrains a seller (e.g. a hotel) to sell at the same price directly as is offered via the intermediary. This prevents the buyer from considering the cost of the intermediary’s service.

[12] Phocuswright 2014

[13] Experian Hitwise analysis of online web traffic

[14] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/do-you-have-paying-guests

Note: Material above Contains Parliamentary information licensed under the Open Parliament Licence v3.0.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: regulation, uk

Photo credit: The fight between hotels and OTAs will be a long and tiring. Nana B Agyei / Flickr