Online Travel Has Many Problems, and Everyone's to Blame

Skift Take

A fascinating new study commissioned by the Travel Technology Association details how Delta Air Lines over the last few years has adopted a Southwest-like approach and has removed its fares and schedules from dozens of smallish online travel sites but also from bigger players such as TripAdvisor, CheapOair, Hipmunk, Vegas.com and Travelzoo's Fly.com, among others.

Delta's goal, along with parallel actions by other U.S. major carriers to limit distribution in a variety of sometimes-subtle ways to online travel agency sites and travel comparison sites such as Kayak and Skyscanner, is to keep fares artificially high by making it much more difficult for consumers to shop around and scrutinize competitors' fares side by side.

That's one of the conclusions of the report, Benefits of Preserving Consumers' Ability to Compare Airline Fares, which was authored by Scott Morton, a Yale professor who served from 2011 to 2012 as deputy assistant attorney general for economics in the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Anticompetitive Behaviors?

There are plenty of antitrust and anticompetitive issues to consider in the report about the airlines' behavior.

By analyzing how rate comparison services in industries as wide-ranging as term life insurance, books and CDs, and automobiles led to rate drops, the study estimates that U.S. airlines' efforts to restrict the wide distribution of flight and services information and to drive traffic to their own websites would lead to U.S. leisure and unmanaged business travelers paying an additional $6.7 billion in airfares and discourages some 41 million passengers from flying because of the high cost of flights.

That $6.7 billion estimate doesn't even take into account higher fares that business travelers, a key focus of the airlines, might be paying because of airlines' lack of fare distribution and transparency. So the estimate would be considerably more lofty if road warriors were included.

How does it work?

The study cites Southwest as having a sometimes-undeserved reputation as a low-cost carrier because of the way it severely restricts travelers' abilities to compare its fares with competitors.

"... recent research shows that the lack of easy access to Southwest’s price information on price comparison websites actually makes Southwest prices higher under certain circumstances," the report states. "This study examined whether Southwest, which does not make its prices widely available to consumers through OTAs, is able to command higher average fares (despite its reputation as a low-fare carrier). The author finds that Southwest’s distribution model prevents travelers from immediately observing competing fares from rival airlines. For last-minute bookings (which the author contends have the highest search costs), Southwest has higher fares on its own website than the best available comparable deal obtained from an Internet site (Orbitz) that allows direct comparison of airlines’ offers."

The Airlines Have Clamped Down Behind the Scenes

Consumers don't realize it when they visit online travel sites but in addition to Southwest historically boycotting online travel agency and metasearch distribution and Delta cutting off its fares from dozens of sites, the study outlines how U.S. airlines, including American, United, and Delta, have also:

- Barred sites like Kayak and Skyscanner from referring travelers to online travel agency sites such as Expedia and Priceline to book flights;

- Told online travel agency sites they can't provide flight information to sites such as Kayak, Hipmunk and Skyscanner;

- And prohibited global distribution systems such as Sabre, Amadeus and Travelport from supplying fare information to "unauthorized" online travel sites.

These steps are all designed to stymie travelers from comparing ticket prices airline to airline, and that helps carriers avoid competition and keep their fares high.

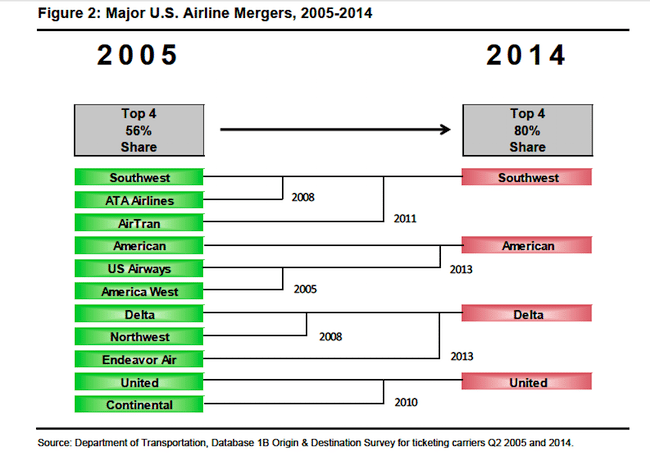

All of these actions take place as the wave of airline mergers (Delta-Northwest, United-Continental, Southwest-AirTran and American-US Airways) has whittled the dominant U.S. airlines to four, which control 80 percent of one-way and roundtrip passengers.

The report goes on to provide commentary on the airlines' market-controlling behaviors. As a rule, they are loathe to increase capacity to keep airfares high and refuse to lower fares despite declining fuel costs.

"Airline executives have recently made statements about pricing 'to demand,' rather than to costs. This is a statement about market power. Under perfect competition, price is equal to marginal cost. Falling marginal cost is largely passed through in the form of lower prices. A monopolist, on the other hand, prices to the demand curve and above marginal cost," the report states.

Airline executives such as United CFO John Rainey aren't shy about touting the better position U.S. airlines are in these days because of a “lack of fragmentation.”

On pricing for customers, Rainey says: “We’ll unbundle products or rebundle them in a way that they are willing to pay more for them."

It's a game of merely repackaging products to squeeze out more money from travelers.

An Important Omission

Morton's report was commissioned for the Travel Technology Association, with members including online travel agency, metasearch sites and global distribution systems. The report is on target in most respects but it doesn't delve into another reason that airlines have been reluctant to distribute their ancillary services through the global distribution systems and the online travel sites: To a great extent, the distributors have been slow and have done a lousy job of offering preferred seats and bag fees when made available.

If the online travel dynamic in the flight sector is problematic, then rate restrictions in the hotel arena have also skewed the market and hampered competition and consumer choice.

The European Union, and individual countries within it, are taking the lead in rolling back certain online travel agency rate restrictions that largely prohibited hotels from offering varied rates to different outlets.

Under pressure from EU countries and courts, Booking.com and HRS (Hotel Reservation Service) have agreed to a certain loosening of these contracts between hotels and the company, and other big online travel companies such as Expedia will inevitably be drawn in.

It remains to be seen whether Booking.com's and Expedia's market clout with their hotel customers will inhibit increased competition and whether any of this will trickle down to the U.S., where the laws that might cover rate parity are different from those in Europe.

Oh Google

In considering some of the big problems and issues that permeate the selling of travel online, we'd be remiss if we didn't mention the way Google, with its virtual search engine monopoly in many markets, hogs search results by pointing users to its own products high up on the page even when other "answers" from competitors might sometimes be better for consumers.

The EU has filed charges against Google and, depending on the outcome, perhaps this will one day shame U.S. regulators into taking up the matter anew.

Google's practices in this realm are a conundrum that not only adversely impacts Google's competitors in travel in a big way but also hurts consumers.

[gview file="https://skift.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/CRA.TravelTech.Study_.pdf"]