Skift Take

It's hard for resorts and hotels to justify costs related to preparing for climate change in the coming years when they can easily pass along costs to future owners. What Miami and other cities need is a sense of shared responsibility.

Florida tourism and climate experts are speaking today at a U.S. Senate field hearing to discuss the threat of rising sea levels, beach erosion, inland flooding and other climate change impacts to the state’s multibillion-dollar tourism sector.

Sen. Bill Nelson (D-Fla.) called the Earth Day meeting in Miami Beach to underscore the need for South Florida to adapt to its changing coastline. The area “is the most threatened by sea level rise in the continental U.S.,” he said last month.

The event will also highlight resilience measures that local governments are already taking, including plans in Palm Beach County to concentrate housing and infrastructure on higher ground and an effort in Hallandale Beach to move the city’s entire drinking water supply away from the ocean.

“It’s going to cost big resources to get cities to be climate resilient, and obviously the tourism industry has a huge stake in making sure that happens so they can continue to flourish,” Christina DeConcini, director of government affairs at the World Resources Institute, told Skift.

Florida tourism—the state’s biggest economic engine—raked in nearly $72 billion in 2012, and about one-third of that money going to Miami.

The southernmost region draws tens of millions of visitors each year to its extensive beaches, swampy parks, coral reefs and luxury oceanfront properties, all areas that are particularly vulnerable to climate change. About three-fourths of Florida’s entire population lives on the coast.

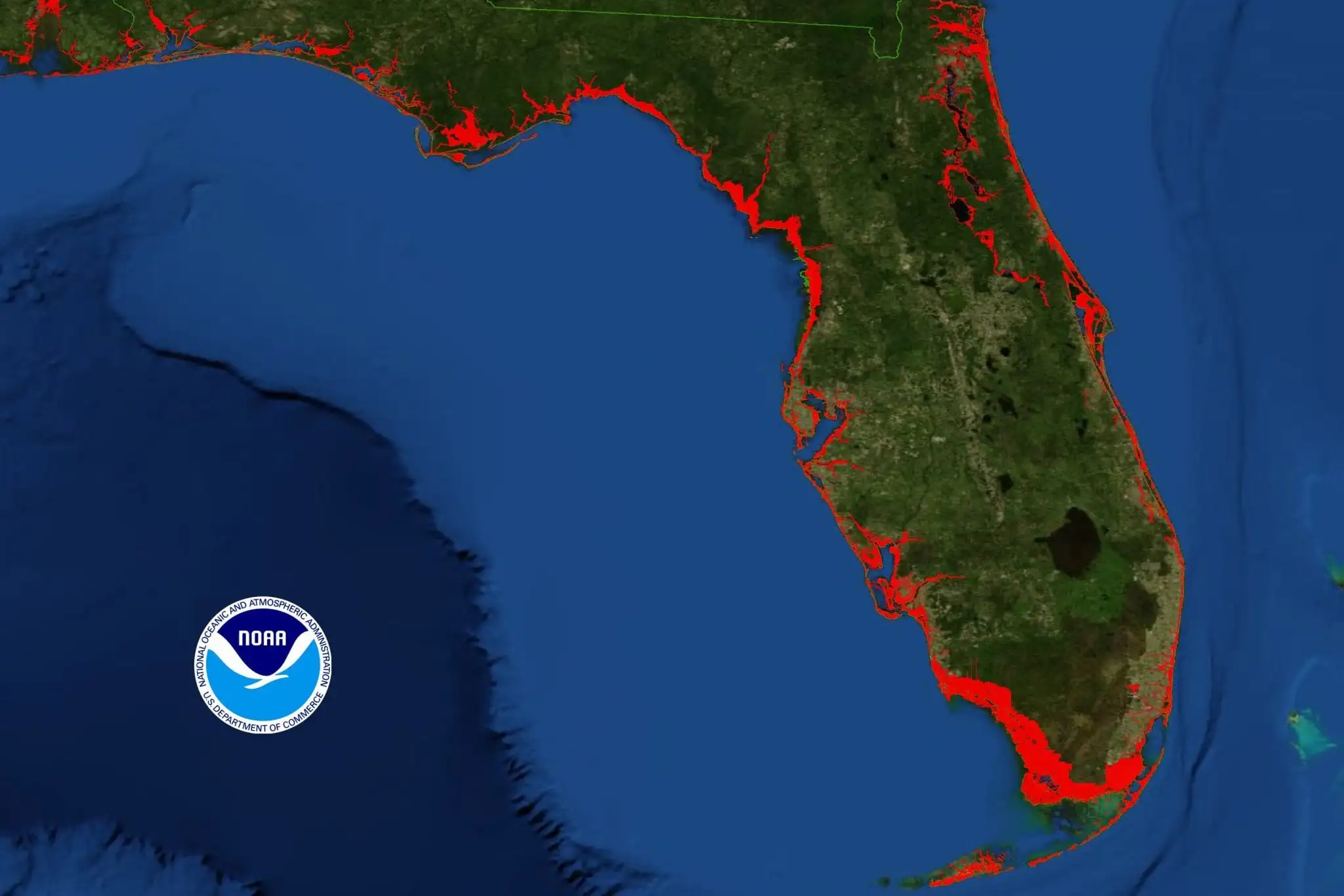

Sea levels in South Florida are projected to rise between nine inches and two feet by 2060, and by up to three feet by 2100, according to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The rise would steadily exacerbate existing problems such as eroding beaches, powerful storm surges and salty seawater flowing into drinking water sources. Higher seas would also amplify the amount of damage from tropical storms and hurricanes.

The financial stakes for Florida’s tourism sector are high. As much as $4 billion in taxable real estate could be wiped out by a one-foot rise in sea level, according to the Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact, a four-county collaboration on resilience and greenhouse gas mitigation. At three feet, the loss could total $31 billion, with major sections of the Everglades, the Florida Keys and the Miami region under water.

Despite the huge risks to tourism, climate experts say that tourism leaders are not doing enough to address the threats. “The tourism industry has done very little to prepare itself for the future,” said Len Berry, who directs the Center for Environmental Studies at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton. “They’d much rather take a short-term view … because [investors] are planning on getting their money back before sea level rise gets to be a major problem.”

Will Seccombe, who heads the state’s tourism marketing agency Visit Florida, responded in statement, writing that the organization’s 12,000 industry partners “are actively engaged with their local authorities on beautification and sustainability efforts.”

The Greater Miami Convention & Visitors Bureau did not return requests for comment by deadline. William Talbert III, the bureau’s CEO, is set to speak at the Senate hearing about the economic impacts of climate change to Florida’s tourism industry.

Such criticism of tourism leaders isn’t unique to Florida. Across the Caribbean region, “coastal tourism has its head in the sands,” said Daniel Scott, the Canada Research Chair on Global Change and Tourism at the University of Waterloo.

Scott co-authored a recent study of nearly 1,000 major coastal resorts in the Caribbean and found that, at three feet of sea level rise, more than one-quarter of the properties would be partially or fully flooded, and more than half would experience significant beach erosion damage. “We think there’s a fair bit of risk there, and [the owners] don’t seem to be looking at it either from a property value or an adaptation perspective,” he said. “Sea level rise is a mid- to late-century issue, and they’re worried about the next quarter.”

In the next few decades of climate change, coastal destinations will likely have to ramp up their beach replenishment efforts, straining existing sand supplies and creating competition for new sources. Properties and cities will have to adopt stricter building and infrastructure designs and update their emergency response plans due to increased flooding and wind damage from storms. Hotel operating expenses could rise as owners pay higher flood insurance rates and invest in expensive backup water and power systems.

Still, Scott said that the forecast is not all doom-and-gloom for coastal tourism. Destinations and properties that do prepare for climate impacts “can gain market share just by being the least impacted of a group. There is a business case for doing these things.”

He said key to climate-ready tourism is “destination resilience” planning, in which private companies collaborate with local governments on regional strategies. Property developers and municipal leaders, for instance, could develop zoning regulations to scoot all new beach resorts back from the water, eliminating concerns by proactive owners of a competitive disadvantage. Scott and his research colleagues plan to develop a first-ever destination resilience plan in Jamaica, Tobago or Saint Lucia.

Berry of Florida Atlantic University said the insurance and re-insurance industries will be critical to pushing tourism sectors to take climate action. In vulnerable coastal areas, flood insurance premiums could rise to such a degree that project economics no longer make sense, forcing developers to build on lower-risk locations.

Berry said he is hopeful that the Senate hearing can foster awareness about both risks and solutions among Florida’s tourism players. “The business folks at the hearing can’t go away feeling complacent when they hear these messages,” he said.

The Senate field hearing will be webcast live at 10 a.m. EDT on April 22 via the Senate Commerce Committee website. Click here for more details.

The Daily Newsletter

Our daily coverage of the global travel industry. Written by editors and analysts from across Skift’s brands.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: climate change, florida, green

Photo credit: The most recent modeling data for a three-foot rise in sea levels, which climate scientists project could happen in Florida by 2100. U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration