What Happens When a Mistake Fare Goes Sideways?

Skift Take

One of the main reasons that I got into the travel industry as an early grad was for the pursuit of airline mistake fares. For many, finding and participating in mistake fares is like an adult version of an Easter egg hunt. They’re almost impossible to find. Each egg has something completely different inside. But when they do show up and when they do work out, the prize can be amazing.

Over the years, both the consumer and the industry sides of the hunt have developed into a science. Sites like Flyertalk and Milepoint fastidiously monitor and report on low and mistake fares in a community setting. Airfarewatchdog manually searches thousands of fares each day reporting on the best prices. The Flight Deal even has an algorithm to automatically monitor and flag millions of fares for discrepancies.

On the airline side, revenue managers have done their best to eliminate as many mistakes as possible, going so far as to monitor the public forums for any egregious errors. For them, a mistake fare is a huge liability; ten thousand tickets sold at $5 instead of $500 can make a $5 million dent, so it’s in their best interest to monitor and regulate the tickets.

In between those two parties is the Department of Transportation, which enforces clear rules protecting consumers against any changes in fare after the purchase point.

Despite parties watching from three sides, mistake fares can and do happen. Depending on the carrier, its management and the route, some lucky passengers have enjoyed $10 fares to Hawaii and $187 fares to Abu Dhabi. In those cases, fares fell squarely within the protections built by the DOT.

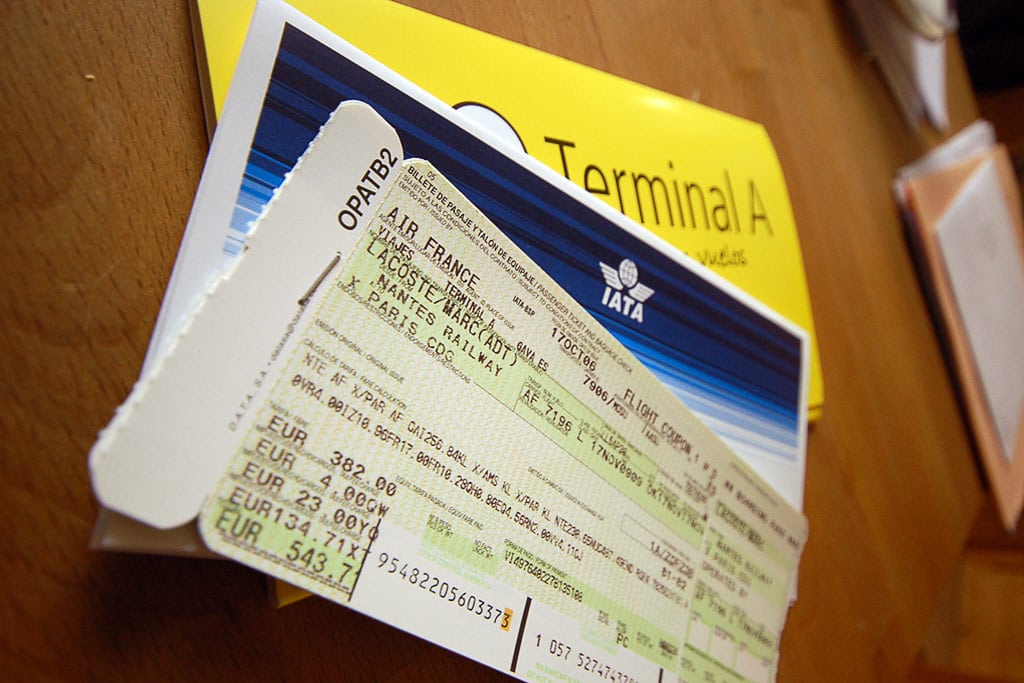

Other fares, however, are not so simple. Last week, a mistake fare published by United sold tickets in Business class from the EU to the U.S. for as low as $51. The error wasn’t necessarily published by the carrier but rather by a third party that converts Danish currency to American dollars — so fault is difficult to assign. And it required that all of the people who purchased the fare to say that they lived in Denmark. Other inconsistencies in price can come from online travel agencies that sell tickets on behalf of carriers, the Global Distribution System (GDS) that publishes the fare, or a handful of other touch points that the tickets travel through during booking. In short, there’s plenty of room for error and for reasonable deniability in the ticketing process. And if airlines have grounds to fight and cut their financial losses, they will.

In cases like United’s business class error, that makes sense. An airline can’t have full control over 100% of the ticketing process and when an ancillary service fails, it can’t be their fault. When the fault is clearly on their side, like in the $10 fares to Hawaii, it’s also fair for the airlines to stick to their commitments — and in that case they did.

At the end of the day though, each mistake fare is subject to an airline’s willingness to support the ticket and to the DOT’s protections overhead. In some cases, for better or worse, the airline gets a pass and they don’t have to honor the ticket — the DOT, for what it’s worth, is currently looking into United’s business class snafu. Other times, passengers are allowed to open their Easter egg and take home the prize. Either way, the hunt will continue.