Lessons From the Demise of Another Failed Travel Startup

Skift Take

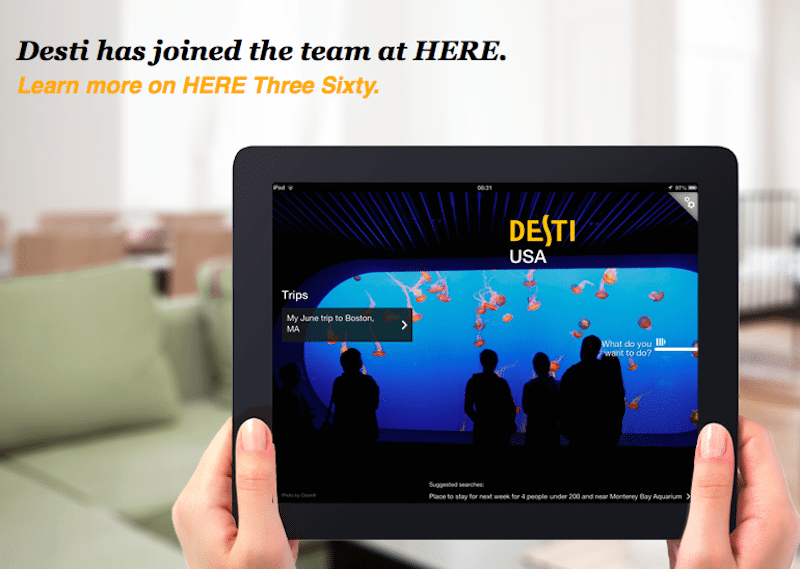

Another trip-planning startup, Desti, impacted by the harsh, cruel realities of trying to compete against much-bigger brands in the travel-consumer marketplace, has flamed out.

In late May, seven of Desti’s nine employees joined Nokia, and its Here maps and location-based services brand plans to use the startup’s semantic search technology to make Nokia maps more responsive and personal. Terms of the acquihire and technology grab were not disclosed. But they’re likely not what the founders were looking for.

The odds were heavily stacked against Desti from its beginnings in late 2011. A spinoff from SRI International, and with total funding of “more than $2 million,” according to Desti co-founder and CEO Nadav Gur, investors included Carmel Ventures and Horizons Ventures.

Gur, who had been the founding CEO of itinerary management service WorldMate, says Desti built a semantic search engine on the back end, analyzing reviews and articles about whether a hotel was known for quality service or whether it was kid-friendly or more nightlife-oriented, for example.

On the front end in the iPad app that was Desti’s go-to platform, Desti sought to provide answers to travelers’ detailed questions such as what is the best hotel in San Francisco for a family of four that’s on the beach and has great surfing for kids.

The premise sounds very similar to Hopper, which also has faced challenges in the extreme.

Gur tells Skift that he and his fellow co-founders Imri Goldberg and Mosi Shuchman, both of whom co-founded trip-planning site Plnnr, learned plenty of lessons along the way.

“It is extremely hard to compete in the consumer market in travel,” Gur says. “In discussions with other entrepreneurs in the space we concluded that you need to have unique inventory like Airbnb. Almost no one succeeds in B2C otherwise.”

In a nutshell, Gur learned that customers found hotels on the Desti app, and then would prefer to book them on the Web from major hotel or online travel agency brands.

“They will go to the channel they are used to,” Gur says. “All you did was help them find a hotel.”

Without getting the revenue and audience it needed to prove itself to investors, Desti got caught up in the Series A-round crunch in late 2013, which finds investors much less ready to bring seed-funded companies to the next funding stage.

Gur wouldn’t comment on the terms of the Nokia acquisition, and how Desti’s investors fared.

He claims the co-founders knew from the beginning that they could hedge their bets and be able to monetize the back-end technology in the travel industry or other verticals. “In hindsight, that is what happened,” Gur claims.

In a blog post, Don Zereski, Here vp of search and places, says the Nokia maps platform will use Desti’s tech “to create a new class of location services that implicitly understands who you are and what you are looking for, sometimes even before you ask.”

Zereski tells Skift: “We plan to use Desti’s Web mining tools to enrich Here’s places database. We first plan to integrate Desti’s semantic search into Here.com and the Here apps, then our platform offering.”

How big is Nokia’s Here brand? “You can find our maps in 4 out of 5 cars with in-car navigation systems,” Zereski says. “As cars become connected, our auto customers are migrating to use Here’s platform services, as well. In the consumer space, Here maps powers customers like Microsoft, Yahoo and Amazon.”

Gur, his co-founders and other trip-planning startups in similar straits, struggling to get into the conversation with big brands that are hardly aware of the startups’ existence, should have realized even before they started that their odds for success were very long.