Tourism Marketers Must Now Go Beyond Optics to Reach Black Travelers

Skift Take

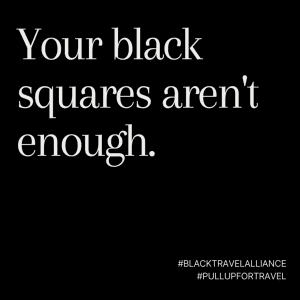

It was early June when many brands, tourism boards, and companies began posting the black squares. Ostensibly a show of solidarity for the Black Lives Matter movement — and the protests that swept across the world after the murder of George Floyd — the gesture quickly fell flat.

The reason for that was simple, say people in the Black travel community: The social media showmanship didn’t match past actions. “The travel industry is one of the whitest industries — which is very odd considering travel is supposed to be this innately inclusive place, but it doesn’t seem to be that,” said Martina Jones Johnson, a travel content creator and founding member of the Black Travel Alliance. The alliance formed in the wake of social unrest from George Floyd’s murder, and the ensuing pronouncements of “Black Lives Matter” from travel brands and companies.

For Johnson and her co-founders, the black squares were a tepid response to an insidious problem that has persisted forever in the travel industry — especially in the context of destination marketers and tourism boards. Tourism marketing is overwhelmingly white, which not only leaves out the huge market of Black travelers, but also perpetuates the racist stereotype that Black travelers don’t belong in certain spaces.

As numerous prominent Black thinkers, activists, and authors have noted in the wake of the recent protests, the national and international awakening about the racial injustice that people of color face feels different this time around. If there was ever a time for tourism boards to not only improve the diversity of their campaigns, but also more profoundly address the stubborn whiteness of the tourism marketing industry, now is that time.

It will come as no surprise that it also makes a lot of business sense to do so. The economic value of the African American travel market increased from $48 billion in 2010 to $63 billion in 2018, according to Mandala Research. And despite not being sufficiently catered for or marketed to, the Black Travel Movement has carved out a space for itself, challenging the idea that Black people don’t travel, or only want to visit certain destinations when they do.

In response to the black squares, the Black Travel Alliance launched the #PullUpForTravel campaign, asking destination marketing organizations and other travel brands to report publicly on five metrics: employment, conferences and trade shows, paid advertising and marketing campaigns, press, and philanthropy. Within 72 hours of launching the campaign, Johnson said they’d received 56 responses — 14 percent of which came from DMOs. Beyond this campaign, the alliance will also serve as an ongoing resource for Black content creators and a space for allies to engage.

The scorecard devised by the alliance points to the holistic nature of the problem. It’s not just a matter of improving representation and launching more diverse campaigns — though that’s important — but rather a total excavation of the many assumptions, blind spots, and practices that lie at the core of the industry.

Those include the relentless centering of white people in the travel experience; the dearth of creative and strategic roles that are filled by Black people, indigenous people, and people of color (BIPOC); and the opportunities and free trips that are given to white people, which beget ever more opportunities and free trips for white people. If the industry is to change and do better — which it must — all these things need to change.

Representation Matters

The reality is that traveling as a Black person is a different calculation, whether it be taking a road trip across America or visiting a luxury property abroad. Mandala’s 2018 report found that 15 percent of African Americans (the report was limited to the U.S.) said that fear of racial profiling would affect their decision to travel in the next 12 months.

That’s part of the reason why representation in travel marketing is so important. Some DMOs including Philadelphia, Detroit, Baltimore, and Bermuda have actively worked to make campaigns more inclusive, but everyone Skift interviewed for this piece emphatically said the overwhelming majority of tourism marketing campaigns they see do not reflect enough diversity.

“Marketing and advertising just using Black people in campaigns may be low hanging fruit,” said Jessica Nabongo, a travel entrepreneur, influencer, and founder of Jet Black luxury travel agency. “[But] that low hanging fruit will move people to go places."

The lack of representation is not only illogical in a business sense, it also actively perpetuates inaccurate and racist stereotypes that have real-world implications for Black travelers. One of the most prominent of these is the idea that Black people don’t belong in luxury spaces.

Nabongo, for example, described being asked by airline staff if she is off-duty crew while flying in first class multiple times. Meanwhile Margie Jordan, a travel agency owner and educator, recently wrote for Travel Weekly about her experience as a frequent Black traveler in the Caribbean — where she is often asked by fellow guests for restaurant reservations or to arrange a taxi.

Pick up any piece of luxury tourism marketing and “see how much diversity there is. It’s completely absent,” Jordan told Skift. “My example of the Caribbean — it’s really a place where I’m considered the help. If you look at their marketing, especially luxury, you see us depicted in there as the help. So I feel like the marketing has perpetuated that idea that ‘okay there’s a brown skinned girl over there, she must work here, let’s go get some towels from her.’”

Representation may be a first step on the long road to making travel marketing less white-centric. But it’s important that this representation isn’t done in a strategically watered-down way, one which ensures the message stays palatable to white people who are used to seeing themselves reflected everywhere they look. Nabongo notes that “it’s important that they target Black people — but not racially ambiguous Black people only, or not just a mixed race family, or just thin beautiful Black people. I think that diversity isn’t just race — it’s gender, body type, age, color. It’s not like we’re all one shade.”

More diversity in marketing campaigns isn’t just about attracting Black travelers to a destination, but also de-centering the white experience. Black people in majority white countries have, for centuries, been forced to imagine themselves in the place of white people in virtually every form of marketing — not to mention pop culture and public life. Part of the work of reversing white supremacy means white people need to be able to do the same.

“I feel like some people may see my company Jet Black and they come to the page and it’s all Black people, and say ’oh this isn’t for me. It’s only for Black people.’ But why would you assume that?” Nabongo said. “It’s not only for Black people.”

Press Trips and Influencers

Another place that the whiteness of travel marketing is clearly reflected is in press trips and the influencer economy, which has comprised a bigger and bigger part of the travel marketing world over the last ten years. Tiana Attride, editor at Here, the magazine of luggage e-commerce brand Away, recently wrote about her experience as a Black woman working in the travel industry.

“I can’t think of a press trip of any size — whether it’s been 60 people or 5 or 6 — I just can’t think of a time when I’ve not been the only Black person in attendance,” Attride told Skift. “Which is unbelievable to think about.”

She notes that these spaces have not necessarily been overtly racist towards her. But rather, it’s a covert feeling where everyone is white, unthinkingly giving more opportunities to and signal-boosting other white people and businesses, thereby making Attride feel like “an invader in a world not meant for me,” as she wrote. She notes that BIPOC-owned businesses are often left out of such trips.

“Most of the businesses I’m visiting when I’m on press trips are going to be white-owned, so that’s who’s getting the majority of the representation. In travel media, most of the people attending the trip are also white,” Attride said.

Not actively courting more people of color to be in these spaces is especially perplexing, Johnson said, because Black influencers, content creators, storytellers, and journalists are arguably far more qualified to market to Black travelers than the best majority-white creative agency will ever be. And travel brands are leaving money on the table by leaving them out.

“Why aren’t there more Black people telling Black stories?” Johnson asked. “When Black people travel and there’s history there, we want to explore that. The white content creator, journalist — they just aren’t telling those stories. It isn’t a part of their culture. They don’t care about it. There’s a huge gap of information and stories that aren’t being told.”

Extend the Invitation

Beyond baseline representation in marketing campaigns and on press trips and social media feeds, there is also the question of actively extending an invitation to Black people specifically. In other words, saying: “You’re welcome here.”

Notable and successful examples that targeted Black Americans specifically include the Go Back To Africa campaign by Atlanta-based travel firm Black and Abroad, as well as Ghana’s “Year of Return” campaign to commemorate 400 years since the first enslaved Africans were forcibly taken to the U.S.

Glenn Jones, the interim CEO for Bermuda Tourism Authority told Skift that “representation is obviously important … but I think it’s also important to extend the invitation. I’m a Black traveler and I certainly respond well when I feel I’m being invited to a destination and there’s a deliberate attempt to do that.”

Bermuda began doing just that in 2018 as part of their National Tourism Plan. Their goal is to double the amount of self-identified African American air travelers who come to the country by 2025, from 4 percent to 8 percent of their inbound market. They do this not only through representation in campaigns, but also by highlighting the nation’s Black cultural history in their marketing collateral and working with Black celebrities and influencers.

Jordan notes there is a great desire and appetite for these kinds of travel opportunities that tap into Black cultural heritage and history in different nations. But not enough tourism boards are elevating them, she said, leaving Black travel advisors to do the work themselves.

“There’s a huge movement of this among travel advisors,” Jordan said of seeking out cultural heritage tours. “What’s happening right now is that the way we’re finding things is we’re communicating in our own Facebook groups, we’re communicating and sharing these experiences — that’s how we know where to find those pockets of culture.”

But not all Black travelers may want to be marketed in that same way. Nabongo said for her — a first-generation American with Ugandan parents — she doesn’t necessarily want her race to be specifically marketed to beyond representation. However, she says, there is an opportunity for tourism boards to market and amplify the Black culture and history offerings in their destinations for all travelers, and in the process start to reverse the erasure of people of color from the history of these places.

“For example I know in Amsterdam and Paris they have these Black heritage tours — that should be a part of the tourism board’s [offerings,]” Nabongo said. “And that program shouldn’t only be marketed to Black people. The heritage of Africans in Paris or Black people in Amsterdam isn’t something only Black people should know about. It’s something that everyone should wish to explore.”

Look Inward

Even if tourism boards ostensibly try to get all of the above right, it can still go wrong. That’s likely to be because they are just thinking about the optics of their marketing output, not the leadership structure, ethos, and people that make up their organization and campaigns.

As Visit Baltimore CEO Al Hutchinson told Skift CEO Rafat Ali earlier in June, "My experience has been that if I had not been in the room to talk to folks in developing a marketing campaign, then it would have been very one-sided. It would’ve just looked one particular way, very white. It is a question of making sure we bring more thought leaders, people of color into the realm, into the conversation so we can have a much broader conversation and a much more honest conversation on what we’re trying to accomplish."

The Black Travel Allliance's Johnson said that's why employment is one of the criteria points on the Black travel scorecard: "We think from that flows getting other things right," she said.

Jones of Bermuda notes that while the diverse and welcoming campaigns are undeniably important, “the potential false narrative here is that the public rewards or scolds brands based on a few words on social media” instead of challenging destinations for a more holistic commitment to de-centering whiteness from the inside and out. As such, Jones said, Bermuda’s tourism authority is “trying to have a committed effort of representation, to articulate the island’s culture authentically, to permanently extend an invitation to Black travelers.”

Bermuda was one of the DMOs that responded to the Black Travel Alliance’s scorecard metrics, reporting that Black people comprised 40 percent of senior management team members, and that 55 percent of people featured in their top five ad spots in 2019 were Black.

Nabongo cautions destinations about getting too fixated on what they present in front of the camera, fearful of being called out, without thinking about the whole structure underpinning it. She recalls being asked to go on shoots where she has to bring her own foundation, do her own makeup, and advise on how to light her shots because the all-white creative team does not know how to work with darker skin.

That said, she is “cautiously optimistic” given the dramatic events of recent weeks.

“Something feels different. It feels like a real change is upon us. What I hope for in the travel space is that it isn’t just lip service. And while I get part of my money from being an influencer, I think it’s also about hiring Black photographers, it’s about hiring Black writers, and marketing executives.”

The Black Travel Alliance's Johnson said she wants tourism boards and destinations to finally treat the Black travel market as it deserves to be treated.

“As tourism boards go forth and make their plans and try to be more inclusive places, I would say to definitely remember that Black people do everything,” Johnson said. “We dive, we swim, we hike, we birdwatch, we do luxury. Don’t put limits on Black people. Don’t put us in your box.”