Opening Closed Doors: Can Hotels Do More to Fight Human Trafficking?

Skift Take

M.A.’s story is not unique, but that doesn’t make it any less horrifying. After leaving home to live with a friend in 2014, she faced being kicked out of her temporary residence. It was around this time, a complaint in a civil suit alleges, she met a person who began posting graphic images of her on the now-defunct classifieds website, backpage.com.

Facing violent threats from her trafficker, M.A. claims she was forced to sell sex for a period just shy of a year and a half. She was subject to visits by up to 10 johns per day. The victimization took place at multiple hotels in the Columbus, Ohio region — including properties branded by IHG, Wyndham, and Choice Hotels, which are all named as defendants in the pivotal civil case. She managed to escape in 2015, and her trafficker was convicted and sentenced to prison in 2017. Though she is an adult now, it has not been made public whether she was a minor at the time of the abuses.

“During the time period she was trafficked, M.A.’s trafficker often requested rooms near exit doors,” the complaint alleges. “Frequently the trash cans in the rooms in which M.A. was trafficked would contain an extraordinary number of used condoms. The trafficker routinely instructed M.A. to refuse housekeeping services. The hotel rooms in which M.A. was trafficked were frequently paid for with cash.”

While M.A. may or may not have been aware of it at the time, all of those indicators above were signs of human trafficking — ones that have become common red flags to watch out for in the hospitality industry’s widespread trainings on the issue in the past few years. Her lawyers claim the hotel chains she stayed at “knew or should have known” she was being trafficked, and did nothing to intervene. The corporate brand hotel defendants as well as the individual hotel properties, which were also sued, deny all the allegations.

It’s a common misconception that human trafficking requires some kind of movement across borders. But in reality, human trafficking's defining characteristic is not movement, but exploitation — it's using some form of control to commodify human beings. According to the UN's definition, trafficking is the harboring, transporting, or recruiting of humans through force, fraud, or coercion for the purpose of commercial sex, forced exploitative labor, and other forms of servitude. The United Nations’ International Labour Organization estimated that 24.9 million people are trafficked globally into forced labor — 19 percent of which takes the form of forced sexual exploitation. Taken as one industry, all forms of human trafficking are worth an estimated $150 billion globally.

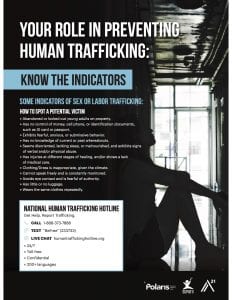

Both human trafficking and travel are inherently global industries. Because of that, the former intersects with virtually every facet of the travel industry, including airlines, meetings and events, tour operators, but especially in hotels. Hotels and motels are one of the most commonly reported venues for sex trafficking in the United States according to Polaris, a non-profit which operates the largest human trafficking hotline in the nation. A study from the Human Trafficking Institute found that 81.5 percent of the active criminal sex trafficking cases that identified a location in the U.S. in 2018 happened at a hotel.

To be sure, human trafficking is not a problem that hotel companies are responsible for creating. The privacy, anonymity, and discretion that their business models offer, however, does unwittingly provide the infrastructure for the trafficking to occur behind closed doors. And it doesn’t matter whether it’s at a high-end or budget property.

“You see these movies and think ‘Oh, it’s the scuzzy guy at the nasty motel.’ It is,” said survivor and activist Theresa Flores. “But it’s also businessmen and politicians, and they’re not going to go to the nasty hotel — they go to the nice hotel.”

It would be incorrect to suggest that the hospitality industry has ignored the issue of human trafficking. On the contrary, the world’s largest hotel company, Marriott, has gotten plenty of positive attention for its corporation-wide efforts since 2017. But the scale and nature of this shape-shifting issue — it happens in every country, at every socioeconomic level, at every kind of property — means it’s hard to measure whether these efforts have brought their intended outcomes. In addition, some critics say, some interventions might be unintentionally harmful to the people they’re supposed to help.

In addition, given a recent uptick in aggressive litigation in the U.S. — M.A.’s case being a leading example — it’s possible that brands are as motivated by protecting themselves from liability as they are by doing the right thing and putting forward an image of social responsibility. At the same time, newer, online-only players such as Airbnb and Booking.com find themselves in an even trickier spot: by reducing some of the face-to-face friction of travel, they’ve also reduced the primary way hotel chains attempt to intervene in such scenarios.

Awareness of human trafficking seems to be growing, at least anecdotally; January is human trafficking awareness month in the U.S, meaning press releases from hospitality brands about the issue are not hard to come by. It’s possible that the increased attention is happening in lockstep with the world’s messy examination of the power structures that have persisted for so long, through stories like #MeToo and Jeffrey Epstein. Whatever the reason, the pressure for the industry to get this right is ratcheting up. The costs of failing to do so are operational, reputational, and — most importantly — they are human.

Corporate Halo

In the context of hotels, when we talk about human trafficking, we’re often talking about sex trafficking. Though labor concerns are arguably just as prevalent, if generally less talked about by hotels. The hospitality sector has responded to the challenge of sex trafficking on their properties meaningfully, if not perfectly.

A benchmark report [link opens PDF] on the travel industry's response to this issue was released in September by ECPAT USA, a non-profit which focuses on ending sexual exploitation of children. (The organization has branches all over the world, with ECPAT International based in Bangkok.) Examining 70 anonymized companies’ actions on the issue, the franchised hospitality sector received a score of 49 percent. The owned and managed hospitality sector scored 43 percent. By comparison, aviation scored the highest score in the sector of 62 percent, while the average score across all sectors of the travel industry was 38 percent.

In addition, each of the seven major hotel groups recently contacted by Skift reported they currently have training policies in place for spotting the signs of human trafficking (see table). Not every company mandated it as a requirement of holding a franchise license. It's worth noting that some jurisdictions, such as the state of California, require some form of training.

| Requirement of being a franchisee? | How often? | Developed with? | Online or in-person? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marriott | Yes | Upon hiring, but revisited | Polaris, ECPAT | Online or in-person |

| Hilton | Yes | Upon hiring and annually | ECPAT | Online or in-person |

| Hyatt | Yes | Annually | Polaris | Online |

| Choice Hotels | No, but offered to franchisees | Did not respond | ECPAT & Dept of Homeland Security | Online |

| Wyndham | No, but offered to franchisees | Upon hiring & yearly (for corporate and managed employees) | Polaris | Online |

| IHG | Only in Americas; offered globally | Upon hiring & yearly (in Americas only) | American Hotel and Lodging Education Institute | Online |

| Accor | Did not respond | Did not respond | ECPAT | Did not respond |

All of the above companies have also joined The Code, an initiative of ECPAT International and the travel and tourism sector to protect children from sexual exploitation. Membership in The Code requires travel companies to implement a six point criteria, including things like providing training, putting a zero tolerance clause in contracts, and reporting annually on its efforts. Founded in 1996, The Code currently has roughly 375 travel industry members from around the world. Members pay a small annual fee to support its secretariat.

If that sounds like a lot of progress, it’s a relatively recent development. Broadcasting that your property is on the lookout for human trafficking doesn’t result in the same corporate halo as, say, eliminating plastics or protecting the rainforest by cutting down on linen replacement. Rather than the positive association other corporate social responsibility measures bring, the disclosure that human trafficking may be happening on a particular property risks raising a starkly negative association to guests. This is in part because guests assume it only happens at seedy properties, rather than the more sinister reality: it can happen anywhere.

The industry, however, has moved away from seeing human trafficking as purely a corporate responsibility activity. It’s equally an operational concern these days, something akin to "having fire insurance or training staff on food prep" said Damien Brosnan, a program manager at The Code. Perhaps hastening this shift was Marriott’s decision, in 2017, to mandate human trafficking training for every single employee (nearly 700,000 in all) at every single property as a requirement of being a franchise holder. The company was the first to do it, which was a watershed moment for the industry on this issue, according to Michelle Guelbart, a speaker and anti-human trafficking advocate who formerly worked as ECPAT USA's director of private sector engagement.

Marriott has also gone front-and-center with its efforts, engaging guests with placards visible in common areas at properties in the U.S. and Canada, and poster contests for employees to raise awareness back of house. The St. Pancras Renaissance Hotel in London’s Kings Cross, a five-star property that is owned and managed by Marriott, hosted an activation day last July educating guests and has also worked with the London Metropolitan Police on other awareness-raising efforts.

Jozsef Ladanyi, head of Renaissance St. Pancras’ safety and security, outlined some of the red flags that both back and front of house employees are primed to look for.

“At reception when someone checks in with a young underage-looking person, it seems like the family bond isn’t there — that trust — maybe the young person seems either intimidated or controlled. Maybe their documents aren’t read when asked,” Ladanyi said. “The person checking in pays in cash, no reservation made, hardly any luggage. If they stay for more than one night, you can see that maybe the victim is wearing the same clothes. They can ask for a room that’s close to exit or away from the lift or in a quiet area of the hotel. Method of payment is cash most of the time."

If a case of trafficking is suspected by an employee who reports it to a manager, hotel management and security generally have two options: involve law enforcement or call a hotline. Hotlines exist in various jurisdictions and countries around the world, some of which are run by governments, others by NGOs or civil society organizations. In the U.S., the federally supported but independently-run Polaris hotline can connect victims to a service provider and resources, and only involve law enforcement if requested. In 2018, 19 percent of Polaris' 41,088 total hotline contacts (calls, texts, emails, and webchats) came from victims themselves.

Whether a hotel contacts law enforcement or a hotline in a suspected case of trafficking will depend on the circumstances and policies. Some chains, such as Wyndham, Hyatt, and Hilton, told Skift their training advises management to make this call on a case by case basis, given an assessment of the information at hand. Others, like Marriott and IHG, said their training advises managers and security personnel to contact law enforcement when enough suspicious signs are present. Choice Hotels and Accor did not respond to a specific inquiry on the matter when responding to questions about their training.

But Does It Actually Work?

Despite all the movement on this issue in the industry, there is little empirical evidence that these prominent interventions — such as the use of hotlines, company-wide trainings, and public awareness-raising — result in lower rates of trafficking or an improved outcome for victims.

A 2011 literature review conducted in the Netherlands considered over 144 studies across 19,000 international titles in an attempt to assess the available evidence of these programs' effectiveness. It concluded that "policies or interventions to prevent or suppress cross border trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation have not been evaluated rigorously enough to determine their effect." The paper’s lead author from the Netherlands Institute for the Study of Crime and Law Enforcement — as well as two other human trafficking researchers Skift spoke to — was unaware of any systematic review conducted since.

Part of this, of course, is due to the nature of the crime. Underreporting is assumed, and commitment to the issue can vary by country — which means the quality of data collected does too. Even in the U.S., where the Department of Homeland Security has a dedicated campaign to address human trafficking, there’s never been a prevalent study done examining whether trafficking is going up or down in the wake of all these anti-trafficking interventions, according to Elaine McCartin, corporate partnerships and training manager at Polaris.

“When it comes to how to measure the efficacy of different interventions, it’s a struggle for everybody in the field because what would you even compare that number to?” McCartin said.

So why does this matter? Firstly, because a lot of resources are going into efforts like Polaris’ hotline. The 24/7 staffed hotline, which is its largest program, cost $4.3 million to run in 2018, partially funded by a grant from the Department of Health and Human Services, the rest by private donors. In addition, both ECPAT and Polaris receive funds from hospitality companies in exchange for providing training, which leaves some wondering if they might have an aversion to outsiders scrutinizing the efficacy of their training.

ECPAT International told Skift it is in the process of updating its e-learning modules for members of The Code, and is always open to input from the private sector and other stakeholders during that process. Executive Director Robbert van den Berg added that the organization's "experience has shown that when private companies receive free training, their commitment to follow up tends to be lower.”

McCartin of Polaris said the organization had “never been asked to have our trainings reviewed by third parties,” and that it is “always open to ways to improve the work we do.”

Kimberly Mehlman-Orozco, an author, researcher, and expert witness on human trafficking is pushing for more peer-reviewed research into the efficacy of these interventions. She said implementing interventions that have not been evaluated or rigorously tested by independent researchers is inherently problematic and possibly harmful.

Mehlman-Orozco doesn’t doubt that big companies are motivated to engage in anti-trafficking efforts as a genuine form of corporate responsibility. After all, she noted, “anti-trafficking is one of the very few truly bipartisan issues.” But an uptick in lawsuits recently appears to provide another motivation. "While it may be perceived as self-serving to some due to the increase in third party litigation, my experience is that hotels are genuinely committed to combating this issue in meaningful ways."

Such lawsuits in the U.S. are a particularly hot issue of late. There is a history of cases where franchise holders are alleged to have a direct knowledge of trafficking happening on their property or to have colluded with the trafficker. In M.A.’s case, Wyndham and Choice Hotels asked to be removed from the lawsuit arguing that M.A. did not plausibly allege that they were liable for any acts of their franchisees. In October of 2019, the judge refused to let them out of the case. M.A.'s lawyers say her case is one of the first times the federal statute called the Trafficking Victims Protection Act is being used to pursue corporate level chains in a civil case; it is moving towards a jury trial.

In other words: liability may no longer fall solely to the franchisee or branded hotel, it may also be corporate's problem. There are multiple similar cases making their way through U.S. federal courts. It’s worth noting that many of the crimes alleged in these suits occurred before trainings and interventions were as widespread in the industry as they are now. While the properties’ policies varied at the time of M.A.’s trafficking, Wyndham, IHG, and Choice Hotels all currently have training policies in place at the corporate level, as outlined in the table above.

Mehlman-Orozco — who serves as an expert witness in such cases — told Skift she finds these lawsuits broadly unhelpful for victims. Though they may result in compensation or support, she said, they also can re-traumatize victims and may result in companies being pressured into hastily implementing interventions to avoid liability, rather than figuring out what truly works for victims in the long run. She also questions the idea that the corporate level of a global hospitality company could feasibly have knowledge of activity at a particular property, where traffickers can go to great lengths to hide their activities.

“In my opinion they have not gone as far as a reasonably prudent company would go to stop this kind of conduct,” Paul Pennock, a litigator from the New York law firm Weitz and Luxenberg, said. He is spearheading a group of lawyers filing similar cases across the U.S. and estimates that as many as 1,500 victims have retained counsel on grounds similar to M.A.'s case, though not all have filed lawsuits. It's worth noting that Pennock says the firm has used advertising to alert sex trafficking survivors that they are willing to represent victims in these suits, a practice that some consider exploitative. He says he is operating out of a genuine desire to eliminate this issue from the hotel industry.

Skift requested comment from Wyndham, IHG, and Choice Hotels regarding M.A.’s case. Wyndham could not comment specifically on ongoing litigation, but said “we condemn human trafficking in any form. Through our partnerships with the International Tourism Partnership, ECPAT-USA, Polaris Project and other organizations that share the same values, we have worked to enhance our policies condemning human trafficking while also providing training to help our team members, as well as the hotels we manage, identify and report trafficking activities. We also make training opportunities available for our franchised hotels, which are independently owned and operated.”

IHG, which similarly could not comment on ongoing litigation, told Skift that “we condemn human trafficking in all forms and are committed to working with hotel owners to fight human trafficking across our industry and in local communities. As part of this, we provide mandatory human trafficking prevention training for all IHG-branded hotels in the Americas, and have been rolling out the program to all IHG-branded hotels globally.”

Choice Hotels did not respond to multiple requests for comment on the matter.

Chip Rogers, president and CEO of the American Hotel and Lodging Association, told Skift in a statement that the industry group launched its No Room for Trafficking campaign in 2019 ”designed to train every single hotel employee in the United States.” He added “every major U.S. hotel brand along with thousands of independent hotels have already begun training their employees … As an industry we recognize the severity of this problem across the globe and are encouraged that more than a million hotel employees have already been trained.”

'A Tricky Situation'

Whether these brands are providing training to limit liability for such cases or out of genuine concern — or, reasonably, some combination of both — there’s another critique. That is, the trainings are focused solely on simply identifying victims, rather than ensuring they get help once they are identified. Kate D'Adamo, a former community organizer for sex workers who now works in anti-trafficking policy and advocacy, said that represents a misunderstanding of how trafficking works.

“You hear trafficking and you might think: ‘Oh this person is obviously trying to run at the first possible chance.’ And that’s often not the case,” D'Adamo said. “Working with trafficking service providers” or organizations who provide resources and help to victims “sometimes it can take a really long time — even with someone you’re working with in an intimate space — to have the right conversation to say ‘okay this person wants my help, wants my intervention, and we have the time and resources to put them in a safe space.’”

In the absence of robust social services, the risk of re-trafficking is also high, she said. “People end up leaving a trafficking situation and reentering vulnerable situations of poverty that create the conditions for being trafficked,” D'Adamo said.

In addition, if law enforcement gets involved — if, say, a hotel called a hotline that refers to law enforcement or calls the police directly — D'Adamo said you could be putting a vulnerable victim who has had very negative experiences with law enforcement in the past exactly where they don’t want to be.

McCartin of Polaris told Skift that the organization is aware of the critique that it's too focused on identification. Through lobbying at the state and federal level as well as with other fact-finding programs on issues like immigration system reform and money laundering, Polaris also works to “help really address and go after these systems that are enabling exploitation to happen in the first place.” She added that the hotline operators are also trained to connect victims with resources such as local service providers, hotel rooms, flights, and transportation to escape vulnerable situations. While the hotline does sometimes refer to law enforcement, it does not do so by default.

ECPAT's van den Berg said that proper identification of victims is "an important first step towards justice," and that in addition to international advocacy work, its network members around the world "[provide] support to survivors, including through running shelters and offering recovery and rehabilitation." It added that "it is not, and cannot be, the role of civil society alone to solve this problem."

Another broad critique of these programs is the potential conflation of human trafficking with sex work. Indeed, many of the common red flags listed in human trafficking detection trainings are also signs of what could be non-exploitative sex work. (Despite centuries of feminist disagreement, sex work is, for some people, just work.) D'Adamo added that higher-end escorts — who tend to have a lower volume of clients — generally do not get targeted by such interventions, but lower-income sex workers disproportionately do.

It’s worth emphasizing that any minor involved in the sex trade is, by definition, a victim of human trafficking. The International Labor Organization estimates that 21 percent of the world's victims of commercial sexual exploitation are under 18 years old. Van den Berg said that while some of the warning signs included in ECPAT's trainings also apply to adults, the nature of the organization's work does not orient itself around adults who can consent to sex work.

McCartin admitted that potential conflation is a “tricky situation” and said Polaris’ training explicitly addresses the issue of conflation of sex work and trafficking by explaining there is a clear difference. “If we want [a victim] to be connected to the right types of services, they have to make that connection of commercial sex plus elements of force fraud or coercion. That’s how you get trafficking.”

Marriott said its training delineates between the two, with Global HR Leader David Rodriguez noting that "our managers — who would make the decision to contact law enforcement — are trained to know that no single indicator signifies human trafficking."

All of these critiques are not to say that everyone thinks these trainings and hotlines do no good. Indeed, no one Skift spoke to suggested scrapping them completely, and anecdotal evidence of their efficacy does exist. But “in addition to increasing our ability to identify,” with more evidence-based training programs Mehlman-Orozco said, “we need to have enough services to help them afterwards.”

D'Adamo added that more of a focus on victim consent before a report is made would be a better way to ensure a vulnerable person doesn’t end up somewhere they do not want to be, such as in front of law enforcement.

A Downside of Frictionless Travel

Another entire facet of the human trafficking problem lies in that other sector of the accommodation industry: short-term rentals. In ECPAT's aforementioned benchmark report [link opens PDF], the sector — which the report referred to as the “sharing economy,” and included ridesharing and homesharing — received the lowest score of 13 percent.

Notably, Airbnb, Booking, TripAdvisor, and Expedia (which owns HomeAway/VRBO), have not joined The Code, despite their traditional industry competitors being members. The Code's Brosnan said that while the operations of these companies are markedly different from traditional hotels, the non-profit would be willing to work with the likes of Airbnb to create a membership model that made sense, as it recently did with Uber in the U.S.

Most troubling is that, for traffickers who seek anonymity, the rise of short-term rentals could be viewed as a boon in an era where hotels have stepped up their identification efforts. “From a trafficker’s perspective, their goal is to run their exploitation business no matter what,” Guelbart said. “So they’re always going to be looking for the most anonymous, least risky way to do that.”

Airbnb began an ongoing partnership with Polaris in 2018 to train back-end customer service staff to respond to concerns that come from hosts, guests, and anyone else — including what to look for and when to escalate a matter to Airbnb’s Trust and Safety team. A rep for the company said it also uses “technology and machine learning to assess the risk of each and every reservation before anything is confirmed.” It declined to go into specifics of what it looks for on the record for fear of divulging information that would be instructive for would-be perpetrators.

Airbnb also screens all guests and hosts globally "against regulatory, terrorist, and sanctions watch lists," but it only performs background checks in the U.S. The company recently admitted to the Wall Street Journal that it's still finding and fixing vulnerabilities in that system. The company also told Skift it works on the matter with INTERPOL, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security's Blue Campaign, and is a founding member of the World Travel & Tourism Council’s (WTTC) global task force to help prevent and combat human trafficking, launched in 2019.

One thing Airbnb hasn’t done yet, however, is engage directly with hosts. That’s a problem, said Michael O’Regan, a senior lecturer at Bournemouth University’s Department of Sport and Event Management who studies the effects of Airbnb and similar companies.

“I think most hosts that I’ve spoken to would welcome some information and guidance around human trafficking,” O’Regan said. “But then again, you have all these issues around frictionless travel and platforms that make it so much more difficult for hosts to actually have any face-to-face interaction with their guests.”

He added that the issue of host engagement was especially important ahead of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics — of which Airbnb is a partner sponsor — as there is plenty of research that has suggested human trafficking rises during major global events.

Airbnb's rep told Skift that it plans to turn its focus to host education in the second year of its partnership with Polaris, “including the development of both online and in-person host trainings.” Polaris confirmed this. Airbnb’s rep also pointed to a recent trust and safety forum in Miami for hosts ahead of the Super Bowl, where the importance of alerting law enforcement or Airbnb customer support if exploitation is suspected was emphasized.

Guelbart said that while host engagement will be key, she sees a broader opportunity for what online players can do down the line if the right steps are taken. “Online booking websites have more opportunity to raise awareness with travelers than most do, so that’s a place I think they should also focus.”

TripAdvisor, which also offers short term rentals in addition to its massive review site, told Skift in a statement it recognizes that “there are very few information platforms at scale that have the capability or influence of TripAdvisor and we know we have a responsibility to do more to help. As such, we are in the early stages of investigating ways we can be a positive force for change when it comes to ending human trafficking.” It added that it is “working towards securing a partnership with an organization to leverage our global reach to educate travelers in our network and mobilize our global community to spot the signs of human trafficking.”

Booking.com, meanwhile, which is the second-largest short-term rental player by number of listings, did not respond to repeated requests from Skift to outline its policies on the issue of human trafficking as it relates to short term rentals. Expedia similarly did not respond to multiple requests.

The Big Picture

It bears repeating that human trafficking is a global problem present in many industries, not just travel and hotels. Indeed, the more one learns about the issue, the more one sees how the meta framework of economic inequality in the world leads to so many vulnerable people being trafficked in the first place.

When asked how she would stop human trafficking if it were up to her, D'Adamo semi-joked it would be matter of: “universal basic income, guaranteed right to housing, dissolving national borders.”

Her economic justice wish list points to the enormity of the task at hand — one that, arguably, corporations cannot be held entirely responsible for. But that said, in the context of the travel industry, there are clear areas of improvement according to advocates and academics: hotels engaging with more victim-centric services at the local level; improving the evidence-based nature of trainings and interventions, including examining how they are administered, how often, and their content; and having a more nuanced understanding that the sex trade is a gradient. In other words, your suspected victim might not be a victim at all.

At a societal level, Mehlman-Orozco would like to see less focus on blaming third parties like hotels, and more on "identifying better mechanisms to address the root causes of sex trafficking and hold the actual offenders liable for their crimes."

As someone who has worked on the issue for a decade, Guelbart senses that the current reckoning with the world’s power imbalances has brought new, much-needed spotlight on this issue. That's something that needs to continue.

“The world that we’re in now in which we’re questioning power structures is one that lends itself well to changing this,” Guelbart said. “The issue of human trafficking at its core is about power and control."

And, as the hotel industry is discovering, those are not easy forces to confront.