Skift Take

After years of being stuck in the past, new "smart" airports are embracing technology and data to improve the experience for both passengers and vendors. But progress is still slow, widening the gap between cutting-edge and archaic facilities. What's needed? More vision, less bureaucracy.

In late September, Beijing unveiled to the world Daxing, a glimmering $11 billion airport showcasing technologies such as robots and facial recognition scanners that many other airports worldwide are either adopting or are now considering.

Daxing fits the description of what experts hail as a “smart airport.” Just as a smart home is where internet-connected devices control functions like security and thermostats, smart airports use cloud-based technologies to simplify and improve services.

Of course, many of the nearly 4,000 scheduled service airports across the world are still embarrassingly antiquated. The good news for aviation is that more facilities are investing, finally, to better serve airlines, suppliers, and travelers.

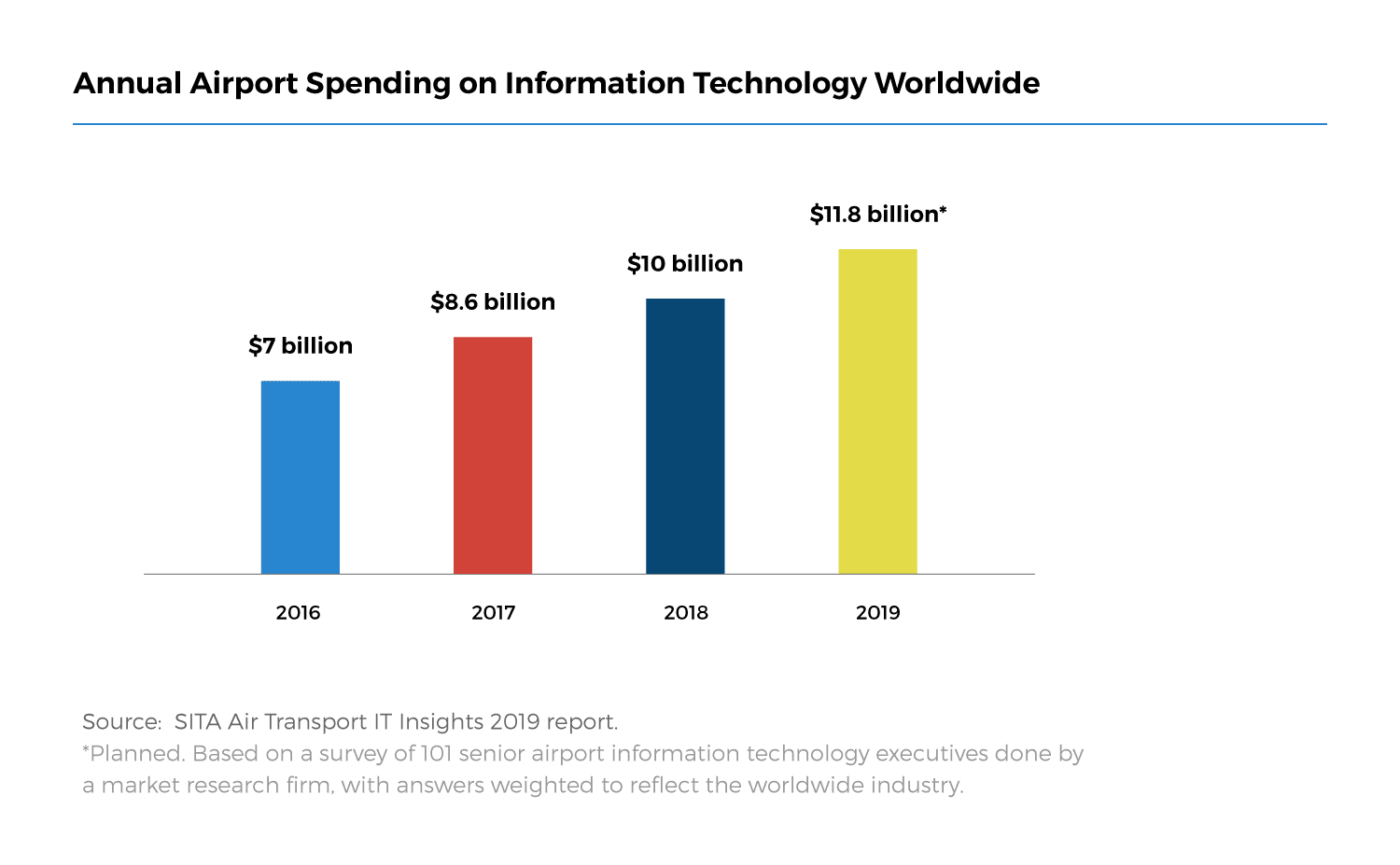

This year, airports worldwide will spend $11.8 billion — 68 percent more than the level three years ago — on information technology, according to an estimate published this month by SITA (Société Internationale de Telecommunications Aeronautiques, an airline-owned tech provider).

A few trends are driving the rise of smart airports. Flight volumes are increasing, so airports need better ways to process flyers. Airports need better ways to make money, too, by encouraging passengers to spend more in their shops and restaurants.

Data is growing in importance. Everything happening at an airport, from where passengers are flowing to which items are selling in stores, generates data. Airports can analyze this data to spot opportunities for eking out fatter profits. They can sell the data to third-parties as well.

Still, a few tensions complicate the transformation to smart airports. A key holdup is strained relationships and finger-pointing among stakeholders over politics, budgets, and process.

Things can go wrong. Just ask Germany. Berlin has spent $6 billion on a new airport that may never open. The story has earned its own podcast called How to F— Up an Airport.

Questions about how data is collected, how it’s shared, and who pays for the new equipment and software are often tricky to answer. After all, airport operators must collaborate with partners such as airlines, concessions, and authorities like border agencies — each with its own goals.

A digital divide may be opening as a result. The rise of smart airports may wrench apart a gap between largely behind-the-times U.S. airports and more innovative ones in parts of Asia, Europe, and the Middle East.

Skift spent months reporting on these challenges. We discovered some airports that are finding creative fixes.

Beijing’s Example

Daxin (pronounced dah-sshing) is at the top of the pecking order for smart airports. It’s applying on a grand scale many technologies trialed elsewhere.

Take robots, for instance. Most airports would rather not. For decades, robots have been little more than toys.

Yet Daxing is at the front of the pack when it comes to moving beyond gimmickry to having robots work with employees on real functions. For instance, Daxing has one robot patrol some of its rooms that house electric power equipment and fire alarm controls. The robot helps to reduce the need for human inspectors and security guards, according to press releases and state media.

Meanwhile, the airport is also testing in one parking lot a robot to grab hold of cars and move them when needed, built by vendor Liting Intelligent Technology.

Daxing leans more on facial recognition technology than airports elsewhere. While many other airports are doing tests of facial recognition as a form of passenger verification, Daxing has made it the default process.

In China, most nationals have their facial details registered in a national database. Daxing’s self-check kiosks can tap into that database to match if a passenger is who they say they are. While many other countries will resist that centralized approach, China’s example shows facial recognition’s potential.

The system isn’t seamless yet at the month-old airport. Foreign visitors continue to have to talk to agents at traditional check-in guests, and all passengers are manually checked by flight crew upon boarding planes as a backstop.

It’s still early days, with the first international flight having landed less than a month ago, but Beijing has a shot at achieving iconic status as a smart airport.

Consider how China Eastern Airlines, the largest carrier at Daxing, goes even further in the embrace of facial recognition. At its lounge, the carrier has equipped some employees with headsets like Google Glass. These headsets have cameras that can scan the faces of elite members of its loyalty program for instant recognition and then display relevant information on an eyeglass-like screen for the employee to provide more personalized service.

Emirates Takes a Tough Line

One tension the rise of smart airports creates is a growing world of haves and have-nots. A divergent technology strategy can, over time, weaken a low-tech airport’s haggling position with carriers when trying to lure more flight service away from a nearby, rival airport that’s savvier with tech.

Consider Dubai. Repeatedly over the past decade, officials in Dubai have said they planned to expand Al Maktoum International Airport, which today handles little passenger traffic, into a modern super-hub for Emirates’ global operations.

Until this year, the government suggested it soon would embark on a $36 billion plan that would allow the airport, sometimes called Dubai World Central, to handle 250 million passengers per year as early as 2030. The project would make the airport almost three times the size of Dubai International Airport, where Emirates is now based.

Despite the dreams, the plan is on hold, perhaps indefinitely. The delay is due, in part, to Emirates growing more slowly amid softness in key Gulf economies. At a September briefing with media, Emirates President Tim Clark identified another problem, too. Airport planners, Clark said, had been slow to embrace new technologies, and he didn’t want Emirates to move into a new airport that was obsolete on Day One.

“My own view is that the design as it was, given the scale it was, didn’t apply technologies to the level that they need to be applied in airport design and passenger flow,” Clark said.

For many years, Clark has been an evangelist for the airports of the future, arguing they must design public spaces differently. Eventually, he said, airports no longer will need sprawling check-in lobbies, maze-like border control areas, or even a central security screening.

“You’ll be able to walk into this wonderful mall of outstanding opportunity around which there will be some airplanes parked,” Clark said. “But don’t forget every step of the way you’re watched, surveilled.”

No one knows when a full shift will occur, assuming it ever does. Clark said he didn’t understand why an airport expansion slated to open in 2030 would need any of those spaces.

No airport will be completely ready when these technologies reach maturity. Yet Clark said a new airport, in Dubai, or elsewhere, should at least consider possibilities into account when designing public spaces.

“I’m not saying that the guys who did all the work so far so well did the wrong thing,” he said. “It’s just perhaps a review needs to take place now as to what it’s really going to look like and what it’s going to do.”

Emirates isn’t just talking about innovation. It’s also testing it. For instance, the carrier is testing at Dubai Airport the substitution of hard copy travel documents with alternative forms of identification such as iris scans and facial recognition for selected flights between Australia and London.

Airlines Are Championing Change

Clark is an airline executive, not a futurist. Nonetheless, he has concrete ideas about how airports in the coming decades will evolve, saying they’ll be almost nothing like today’s.

A tech-savvy airport can benefit an airline, Clark said, because the carrier will be able to re-deploy resources in higher-value services elsewhere.

In a best-case scenario at a well-designed new hub, Clark said Emirates calculated it could remove as many as 2,500 employees per shift just by removing the check-in lobby. He said passengers would hardly miss the check-in stands.

‘Imagine you’re coming curbside,” he said. “I’ve checked in, they know me. In fact, at home, the baggage label has been printed. I stick the bag on the machine, and it goes down the belt. And you just get in, and you walk. Boarding cards will be gone. Passports will be gone. An anachronism. Why do we need passports?”

At the gate, the situation would be similar, he said, with carriers also relying on biometrics. Some airlines are already using this technology, though passengers usually can opt-out.

“You have machines and robots doing it, so it’ll recognize you, and you’ll just walk up to the machine,” he said. “You just get on the airplane.”

Eventually, he said, security services will use artificial intelligence, facial recognition, and subatomic particle analysis machines to know who is a threat without searching bags or bodies. He acknowledged privacy concerns while suggesting those will work themselves out, if only because passengers will appreciate new freedom.

Security services, he said, can make more sophisticated calls about who is a threat when “they know that Max always travels with a razor, toothpaste, deodorant, et cetera,” Clark said. “I can tell you what you’re going to be wearing and carrying in your bag before you even pack it.”

Competition for Routes and Retail Spending Are Key Drivers

Competition for high-spending travelers is another factor fueling the spread of smart airports.

As recently as a decade ago, the biggest airports mostly catered to the whims of airlines, their largest tenants, which often sought the cheapest possible costs.

Today, most airports view passengers as key, said Sébastien Couturier, head of innovation and corporate venture at Groupe ADP, operator of Paris Charles de Gaulle and many other airports.

Airports know many passengers have choices among airports. A business or leisure traveler flying from Berlin to Tokyo can stop in nearly any major hub, including Frankfurt, Paris or even Helsinki.

If a passenger has a poor ground experience, “you will recall this airport in your mind, and you will try to avoid this airport next time,” Couturier said during an interview in September at the World Aviation Festival in London.

Another factor driving tech adoption at airports is that their operators are answering to a commercial incentive, an unmet demand for better shopping.

No airport has placed a big of a bet on retail as Singapore’s Changi Airport, which aims to be as much of a destination for shopping as a place to catch a flight. It generated about $2 billion, or about $20 per passenger, in non-air revenue last year.

This year, Changi opened Jewel, a $1.3 billion ($1.7 billion Singaporean) 137,000 square-meter retail, dining, and attraction landmark to boost revenue further.

Easier Airport Security May be Coming

Daxing airport isn’t alone. Several airports worldwide are turning to new technologies to up their game.

Passengers frustrated by having to remove liquids and laptops from their carry-on bags can take heart in a plan announced by London’s Heathrow.

The airport recently said it would spend about $63 million (50 million) on new computed tomography security equipment across terminals by 2022.

The technology, which is more sophisticated at scanning inside bags, might end the need for passengers having to put their liquids in separate plastic bags and remove laptops at security checkpoints.

In the meantime until the tech is proven, Paris is taking an intermediate step when dealing with the ban on larger liquids. While most regulators have banned liquids in amounts larger than 100 millimeters for at least a decade, many passengers still arrive at checkpoints with items that are not permitted regardless.

“The agent will take it from you and throw it into the garbage can in front of you,” Couturier of Groupe ADP said. “This is one of the biggest pain points passengers can experience.”

Officials at Paris Charles de Gaulle and Orly airports were looking for a solution, and they found it in a conspicuous place. Both airports now have post offices. Couturier joked the French postal service is not usually known for innovation, but here it provides a valuable service.

“They offer you the possibility to send back to your home this object, which is prohibited,” he said. The service, he said, has a customer satisfaction rate of more than 99 percent.

U.S. At Risk of Falling Behind

Compared with Paris, Beijing, and Singapore, U.S. airports have, broadly speaking, under-invested in technology.

A case in point: American airports typically leave U.S. Customs and Border Patrol in charge of zones for processing international arrivals. The agency, in turn, lacks a cutting-edge method to suss out wait times and passenger line, or “lane,” lengths.

The agency is aware of the problem and is testing options with vendors. That said, it may take years for it to deploy nationwide passenger tracking systems that use video, sensors, and other tools to help route passengers to the shortest lines and identify chokepoints that need resolving.

The issue here is a lack of investment. The tools already exist to make rapid efficiency gains. A variety of sensors and the recent debut of so-called three-dimensional cameras can pinpoint bottlenecks and their causes. Operators can study the feedback to inform their plans for renovating facilities and building terminals.

Already, the U.S. is behind. Think of the typical airport parking lot. Today, passengers at European airports, even small ones like in Manchester, UK, commonly pre-book airport parking online.

Not so in the U.S., where few airports tap the latest software to study the supply and demand of parking spaces and manage prices.

“Consumers are trained to order everything on their phones in advance,” said Alex Shartsis, CEO of revenue management vendor Perfect Price. “So why aren’t more airports making tech investments in response to consumer behavior?”

One exception is Raleigh-Durham, where the airport has this year been working with the vendor IDeaS to roll out dynamic pricing.

Beijing’s Daxing is already there. Drivers can access real-time information on their phones about available spaces to park in the lot by using an e-commerce app many Chinese have already downloaded from JD.com, an Amazon-like retailer.

What happens if U.S. airports become even more traumatic to use because of ever more antiquated aspects? Some events organizers might seek alternative host cities like Toronto, Edmonton, and Vancouver that have invested instead in making it easier for travelers to get in and out.

Perhaps the most tantalizing story of potential progress is in San Francisco.

United Airlines last month said it plans over the next year to work with tech giant Apple to improve the passenger experience in its part of San Francisco International. Linda Jojo, executive vice president of technology and chief digital officer at United Airlines, during a media event, didn’t provide details when revealing these nascent plans at a media event, though it’s easy to imagine possibilities for collaboration.

A Major Tech Takeoff From Many Minor Actions

Paris Charles de Gaulle focuses on simple innovations that improve the passenger experience. Yes, someday airports may use futuristic technology to rethink the entire passenger journey. For now, Couturier of Groupe ADP said it makes the most sense to fix little things that irritate travelers.

“The question is, how can we make the passenger journey more simple and smoother,” he said.

That extends to queue management. Recently, Groupe ADP updated the mobile application used by employees. It connected the app to sensors in each terminal, so workers have information about where the crowds are, and where they’re not.

“It’s a great way for them, in a huge infrastructure, to know exactly what is happening in terms of flow management so that they can reallocate resources in real-time situations,” he said.

To be sure, Couturier said he still spends plenty of time thinking about more radical changes that could come to airports in the next decade. Among them is how to use biometrics so passengers can go through the airport without friction. Charles de Gaulle has used biometrics for some security checks.

“The whole approach on this topic is to be able to make autonomous your journey through biometrics from the entrance of the terminal to the boarding gates,” Couturier said. “We will be ready by 2024 to have it deployed for all airlines in Charles de Gaulle and Orly.”

Beyond Paris and worldwide, tensions among various stakeholders are holding back broad progress as carriers test biometric forms of identification with tech from vendors like Clear and Veovo.

“Biometrics will be key to passenger experience, but we need to implement some standards and agree to the rules of the game, making sure players can share data in a safe way across borders and systems,” said SITA CEO Barbara Dalibard. “The industry needs to collaborate.”

The next frontier might be “emotional recognition” software. While still early and speculative, new software studies human responses to questions to suss out if they may be lying. Bucharest airport has tested Avatar, a virtual border guard, built by Discern Science.

A Trend Affecting Small Airports Also

“The perception is that the smart airport trend is only happening at large airports,” said Christelle Laverriere, a market researcher at SITA. “But we see smaller airports also streamline their processes with automation and better B.I. [business intelligence] software.”

Take the case of Uruguay. While its main airport, Carrasco, handles smaller volumes of passenger traffic, the airport also hands a high percentage of international travelers. Processing international passengers can slow down operations. So Carrasco airport has a lot to gain by embracing new technologies.

This year, passengers on all Latam Airlines Group international flights out of Carrasco airport in Montevideo, Uruguay, began to have the option of using self-service biometric boarding at departure gates using technology from Portuguese vendor Vision-Box.

Meanwhile, Indianapolis International Airport tapped vendor iinside to track passenger movements at security checkpoints with Lidar, which uses safe, invisible laser beams to detect objects both in motion and at rest. Other airports are doing similar experiments.

A Call for “Digital Master-planning”

Digital questions often aren’t on the minds of people writing the checks for airport refurbishment and construction or the contractors who are experts in, say, pouring concrete.

Airport planners sometimes outfit buildings without an eye on a digital future.

The humble parking lot showcases some potential problems. Let’s say autonomous vehicles catch on. If electric cars become commonplace, lots may need plentiful charging stations. Yet some of today’s concrete structures aren’t built to allow for that.

A related point: If airports want to maximize their revenue, they’ll want to vary parking prices dynamically by shifting demand. Smarter pricing necessitates automated sensors to track how full lots are.

New technology in airport lots will need reliable internet connections to work. That means overcoming the obstructions and signal interference that are common at many airports today. One fix may be fifth-generation, or 5G, wireless internet service, which can send more data faster. Daxin has 5G, of course.

For airports overall, hiring well can help future-proof plans. Since August 2018, Dallas Fort-Worth has put together a seven-person innovation team. Pilot projects at the innovative airport include having an EasyMile autonomous vehicle ferry passengers to and from a remote parking lot.

Another tension for airports to resolve is how to create more positive collaboration among their so-called stakeholders. An airport operator, the airport authority overseeing it, the airlines, the retailers running shops, and the local municipality may all have different data needs and their own data collection tools.

If the partners don’t share data in a way they all can access and interpret, the full potential of a smart airport will remain out of reach.

“Many large airports are way too protective of their perceived data monopolies,” Stephan Uhrenbacher, a tech entrepreneur who worked with many airports while trying to build a startup called Flio, said in a recent interview.

Uhrenbacher noted exceptions included Amsterdam’s Schiphol. Since 2017, Schiphol has been giving third-party developers access to non-critical business data to help encourage creativity.

“I’m quite surprised by the lack of digital maturity across the sector, with airports, airlines, and border agencies, in that we work in very siloed and non-standardized ways,” said Tara Mulrooney, vice president, technology, at Edmonton Airport in Canada.

“The positive way to look at it is that the air transport sector has a huge opportunity to improve by adopting proven best practices from other industries,” said Mulrooney.

Some airport operators are attempting to overcome inertia with “collaborative decision-making workshops,” where stakeholders work together to learn best practices in decision making and process design.

“Smart airports are more collaborative in sharing data with the different players, like the ground handlers, the retailers, the airlines,” said Laverriere of SITA. “It’s happening to some extent through investments in B.I. They’re aggregating the data and sharing the data and insights about the data.”

Vendors need to up their game, too.

“Airports need to push our tech vendors much harder to provide services like operational databases that are much more open,” Mulrooney said, who joined Edmonton Airport earlier this year after working for a utility. “Our industry’s enterprise software could be much better compared with what’s available in other sectors.”

A related headwind is so-called “vendor lock.” Imagine it’s 1999 again, and you’re an airport that hires a contractor to deliver Wi-Fi for passengers in your terminals. If you sign, say, a 10-year contract, you’re making a bet that the vendor will remain the most competitive option a decade from now. That’s risky.

What’s Next for Smart Airports Worldwide

Technology may help solve several pain points for passengers.

Take the need to reduce the need for passengers to haul their checked luggage to the airport. In London, a startup named Airportr is working with some airlines to pick up bags at a passenger’s home and take the bags to an airport for check-in. In Australia, Oacis provides airport baggage transfer and airline check-in at other locations, such as at ports for cruise lines.

In all such cases, the workflows require airlines and airports to sync up their baggage processing systems with third-party vendors.

The underlying concept behind these services is more profound than it may first look. Someday major airports could deliver luggage straight onward to a traveler’s hotel or home as a service on behalf of airlines.

“Smarter baggage management could save precious real estate at airports, especially air passenger traffic booms over the next decade,” said Bonny Simi, president of JetBlue Technology Ventures, the innovation and investing arm of JetBlue Airways.

China Eastern is tapping other technology to smooth the baggage-handling process. For instance, it’s offering electronic luggage tags that have screens displaying necessary details. The tags connect to sensors at Daxing via tiny radio transmitters. The tags can update passengers on bag location via the airline’s app. Qantas, Delta, and a majority of other significant carriers worldwide plan to offer some version of tracking power by the end of next year, SITA said.

Improving road traffic is another smart airport effort. In New Zealand, Auckland Airport has worked with authorities in the capital city’s central business district to reveal a connected view of traffic between the city and airport. The technology analyzes a mix of radar and Wi-Fi signals.

The data has enabled the city and airport to untangle traffic snarls, such as by optimizing traffic signal timings and anticipating delayed passenger arrivals.

The Auckland story points to a larger truth. Some cities see airport funding as a subsidy for wealthy, non-resident business travelers. Yet investing in a smart airport can provide dividends for everyone in the region.

“Airports are a microcosm for testing concepts that cities need to look at,” said Mulrooney of Edmonton. “They’re a great place for testing ideas like improving traffic flows that cities will need to adopt over time.”

Lodging is another improving area. Beijing’s Daxing opened with an in-terminal hotel, Aerotel Beijing, that lets guest check in anytime, rather than at a specified time of, say, 3 pm. Aerotel also lets guests book stays by the hour.

The airport hotel can do this because its operator has built a property management system for taking reservations and managing rooms to be more flexible than legacy systems.

Bag processing is also improving. In Japan, Narita Airport is installing between now and next summer 72 self-service bag drop machines across its terminals. While not new as a concept, self-bag check’s standardization should speed up flows before the 2020 Summer Olympics crush.

A decade from now, airports may commonly run “digital twins” where decisions are centralized and often automated and tests for new processes can be run virtually.

Making Gains in Accessibility

Smart airports take into account that some passengers may have physical impairments and need help with accessibility. New tech can paint a finer picture of airport operations and let operators fine-tune their wayfaring and accessibility services. Operators can provide more reliable service for wheelchairs and motorized carts, for example.

Airports like Miami and San Diego have put into place beacons that transmit radio signals and track passenger flows, which can help with accessibility. In a similar vein, All Nippon Airways (ANA) has tested self-driving electric wheelchairs at Narita.

Meanwhile, Pittsburgh International Airport has begun testing a smartphone app called NavCog that helps the visually impaired navigate through the airport. The app relies on signals from Bluetooth-enabled beacons to provide directional help.

New sensors can help boost accessibility. Amadeus Ventures has invested in Situm, a company whose technology detects signals like magnetic fields, Bluetooth, and Wi-Fi that smartphones emit. Situm merges those signals with data from the internal sensors of smartphones, such as the digital compass, gyroscope, and accelerometer. It plots all the data against venue floor plans.

Situm’s not the only game in town. Better indoor mapping technologies from companies like LocusLabs, for instance, can pinpoint every inch of a terminal. Data like that could help robots guide wheelchairs to precise locations.

In the meantime, many visually impaired travelers can use an app called Aira for help at 48 airports in the U.S., Canada, New Zealand, and Australia. Say you’re blind, and you go to the airport to fly. The Aria mobile app provides a real-time video feed of where you’re walking, which the agent can watch to guide you through the airport with voice-over instructions.

Blockchain’s Rare True Promise

The media and some investors have much-hyped blockchain, or distributed ledger, technology. So far, companies haven’t found many practical commercial uses. One exception may be with passport control.

“Blockchain has significant potential to be a better way to enable the exchange of passenger data across borders for immigration purposes,” said SITA CEO Barbara Dalibard.

The technology may help to address the regulatory problems around data collection and data protection. Blockchain-based processes may help validate the accuracy and integrity of personally identifiable information, while ensuring the underlying data is secured, can’t be read by unauthorized parties, and isn’t stored.

Cracking the problem of passenger identification could also let airports remove many of the points where travelers have to identify themselves.

Last month, a startup called Zamna aims to help the aviation sector use blockchain to share data. One of its investors and trial partners is IAG (International Airlines Group).

Currently, Kuala Lumpur’s main airport is testing a blockchain-based approach to sharing data. It is sharing facial recognition data for passengers on select flights on Malaysian Airlines.

The Climate Change Wild Card

The climate emergency may also pose a challenge.

The biggest unknown is whether aviation will grow at the same torrid pace if the public decides to cap carbon emissions. Banks, investors, and governments may someday pull back on lending and subsidies. Intensified storms and air turbulence may take the shine off of jet travel.

For now, many airports are focused on boosting their energy efficiency.

Norway’s largest airport operator, Avinor, has been a leader in sustainability. By the end of next year, Avinor believes it will have cut its controllable greenhouse gas emissions in half compared with 2012 levels.

Even small airports like Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania’s, have plans. Pittsburgh’s airport recently said it would be the first airport in the U.S. to operate its own power grid via eight acres of solar panels, supported by five gas turbines.

“As we went through the plans for the new terminal, it became a natural question of why can’t we power it ourselves?'” said Christina Cassotis, CEO-Allegheny County Airport Authority.

“Atlanta had gone down for a day [Atlanta’s airport lost power for 11 hours in 2017, paralyzing its operation.],” Cassotis said. “We all looked around and had that resilience question of, ‘Are we completely comfortable that, no matter what, we can operate?’ And felt that we really wanted to ensure resiliency while we improved our sustainability footprint and lowered our costs. We realized we could do it through the microgrid.'”

Solar panels are an easy win. Look at how Dubai Airports and Etihad Energy Services have plastered the panels at Dubai International’s Terminal 2.

Beijing’s Daxin is attentive to sustainability, too. Along with solar panels, the airport may use green power for at least 10 percent of its annual energy needs. It will tap geothermal energy and use software to power up and down electricity use based on demand.

An Optimistic Future

Smart airports are in vogue because of a dawning realization that the aviation industry will likely expand beyond its current capacity. Airports will need tech to handle the crush of more passengers.

If the middle-class continues to expand worldwide and if flying remains popular despite climate change, the world may double the number of jet airliners in service by 2040, predicts the industry lobby the International Air Transport Association.

Spending trends are a cause for optimism. Worldwide, this year airports will spend an average of 6 percent of their revenue on information technology. That is roughly double the amount they spent on conventional capital expenditures, SITA said.

Data will be a game-changer, letting airport operators turn uncertainty into opportunity. Yet airport operators need to stay focused on the traveler as they prioritize their tech investments.

“Automation, A.I., data management is in the larger service of providing more predictability in the passenger experience,” said Bruno Spada, head of Airport IT at Amadeus.

The most significant skills that operators need often aren’t so much technical as interpersonal. Executives need to tap good-old-fashioned diplomacy to bring partners together.

The smart airport trend is, after all, about something more than robots, scanners, and sensors. Exhibit A: Daxing — whose name in Mandarin can mean “great flourishing” — will signal to the world Beijing’s future.

“Once they were in the outskirts, supplementing cities, like train stations,” writes Olga Tokarczuk, the winner of the 2018 Nobel prize in literature. “But now airports have emancipated themselves so that today they have a whole identity of their own.”

Additional reporting by Skift Airline Weekly Editor Madhu Unnikrishnan.

The Daily Newsletter

Our daily coverage of the global travel industry. Written by editors and analysts from across Skift’s brands.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: airline innovation, airport design, airport technology, airports, amadeus, deep dives, emirates airlines, sita, smart airports

Photo credit: The main hall of Beijing Daxing International Airport in October 2019, one month after its opening. British Airways