Skift Take

U.S. airlines are still struggling to recoup their higher fuel and labor costs. But as their fourth quarter results showed, they’re making progress. How? With help from some strong revenue tailwinds.

A sharp drop in fuel prices midway through the fourth quarter of 2018 was welcome. But it didn’t prevent U.S. airlines from paying 24 percent more for their fuel this fourth quarter versus last. So once again, industry margins declined. But not much.

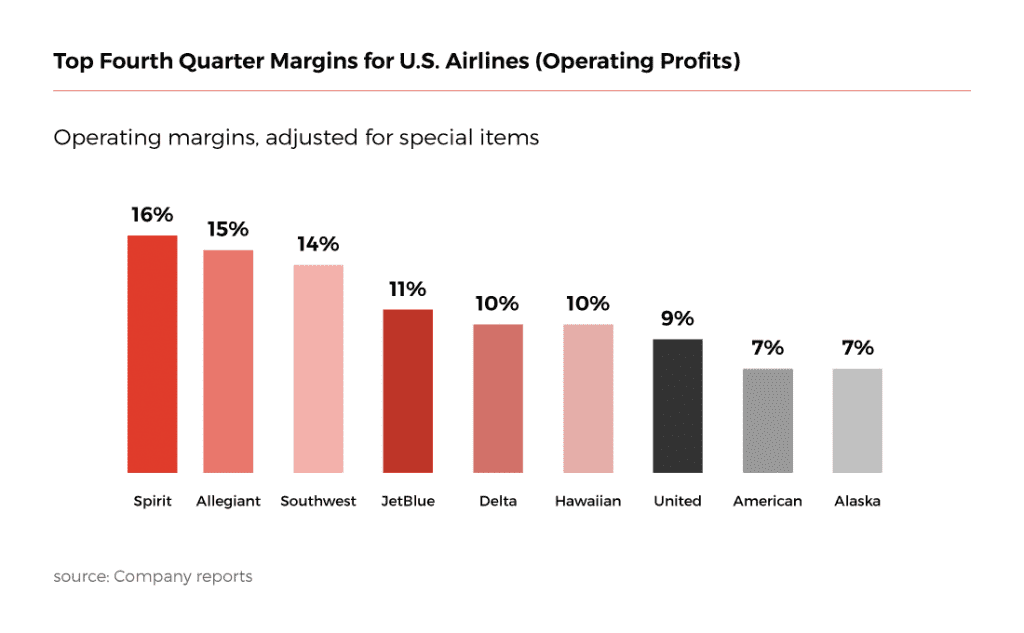

The country’s nine largest scheduled airlines that have reported (Frontier hasn’t yet done so) collectively earned a 9.7 percent fourth quarter operating margin, down just slightly from 10.4 percent a year earlier. Full-year margins fell more substantially, to 10.4 percent from 13.1 percent.

But by the second half of 2018, industry fares began firming, helping to offset much—but not all—of the steady fuel inflation that persisted through mid-October. Better pricing helped mitigate ongoing labor cost inflation too. In the second and third quarters, not one major U.S. airline managed to increase its margins year-over-year. But by the fourth quarter, a few—led by Spirit—did.

The big story last quarter was indeed stronger revenue trends, aided by firmer pricing. As airline executives often say, revenues eventually catch up to higher fuel prices—it just takes time. But maybe too much time. Because remember that 10.4 percent operating margin for all of 2018? Well, it was the worst industry figure since 2013.

That said, anyone with memories of last decade will feel supremely pleased with double-digit industry margins of any kind, even if just 10 percent. Sure, 2015’s 17 percent operating margin was nice. But replicating that every year is hardly the measure of success. Maybe a better measure of success is comparing U.S. airlines with their counterparts abroad. In that regard, they’re still big winners, still benefiting from the consolidation that European airlines now seem eager to mimic.

U.S. consolidation is done, albeit with some synergies from past mergers still left to harvest, most importantly at Alaska Airlines. United and American too are just now realizing benefits from fused flight attendant workforces. That’s not why revenues were so strong last quarter, though, rising 7 percent on just 5 percent more available seat miles capacity. Every U.S. airline except Hawaiian, in fact, grew revenues more than capacity, some substantially more.

What are the reasons why revenues were strong, beyond just a firmer pricing environment?

13 Takeaways

For the U.S. Big Three, demand was strong both at home and abroad, and both for business and leisure. But more specifically, they benefited enormously from flourishing long-haul premium demand, even more specifically in three key markets: Europe, Asia and domestic transcontinental. JetBlue also benefited from the latter.

JetBlue was likewise among the carriers benefiting from strong domestic short-haul business demand—this was most helpful for Southwest. The Big Three benefited as well, to be sure, if not quite with as much satisfaction as they got from the long-haul premium bounty. Alaska was a winner here too, although its top business markets from Seattle and California came under heavy competitive fire.

Thank heaven for Florida: Ultra low-cost carriers keep piling into the sunshine state, with seemingly endless success. The trend applies to the Caribbean too. And it helps JetBlue, Southwest and the Big Three as well. What makes Florida and the Caribbean thrive, of course, is strong inbound tourism from economically booming cities across the eastern U.S.

Originally designed as an ultra low-cost carrier repellent, basic economy fares are helping airlines upsell to higher fares, thereby increasing revenues. Now Hawaiian is preparing to offer a basic economy fare option—and it doesn’t even compete against ULCCs. JetBlue is adopting it. Alaska now has it. And the Big Three are spreading the concept far and wide, even across the Atlantic.

The basic economy phenomenon stems from a broader segmentation effort that clearly and concisely markets different sets of products to different groups of customers with different needs and wants. Southwest, the most highly bundled U.S. airline, is not playing the basic economy card.

To really get the most out of their segmentation efforts, U.S. carriers need to achieve consistency in what they offer customers across all booking channels. Unfortunately for them, this has not been the case.

They’ve been running full-speed ahead with advanced merchandising and customizing on their own websites and mobile apps but have been hobbled in their ability to do the same through travel agency channels. That’s changing, however, and providing yet another revenue tailwind.

IATA’s standards for its New Distribution Capability are helping, as third-party booking sites increasingly can offer a wider selection of an airline’s products from preferred seating to early boarding. So do evolving relationships with global distribution systems. There’s more work to do, though. As a United-Expedia dispute shows, moving ahead sometimes involves confrontation, not just cooperation.

Some once-trendy initiatives like seating densification have largely run their course, further reconfiguration work at JetBlue, American and others notwithstanding. What’s still very much in fashion, by contrast, is partnering with airlines abroad. Some newish partnerships, such as Delta’s joint venture with Korean, are still just ramping up.

And many more await regulatory clearance, including Delta’s proposed joint venture with WestJet and its bid to unify its transatlantic joint ventures with Air France/KLM and Virgin Atlantic. Heck, it might even buy a piece of Alitalia to keep it an ally. American has its own set of promising partnerships with LATAM, China Southern, Aer Lingus and perhaps Qantas.

United hopes to fortify its Latin American credentials with an Avianca/Copa joint venture. Will it next—finally—share transborder revenues with Air Canada? Hawaiian is giddy about forming a JV with Japan Airlines. Alaska is doing interesting things with Qantas and might even affiliate with the Oneworld alliance. Might even Southwest opt for cooperation with airline partners abroad?

Ancillaries are still a growth area too, thanks to success in raising bag fees, bundling offers, revenue-managing fees and more effective distribution and customer targeting. Loyalty plans, too, remain massive cash cows, supporting lucrative credit card deals. There’s some long-term concern, though, that airlines might be reaching peak co-branded credit card revenue, with future rounds of negotiations perhaps less fruitful. Spirit, for one, is revamping its loyalty plan.

Behind the scenes, airlines are getting better at revenue management. How? Through experience, in part, but also better revenue management science and better data. Southwest took a big leap when installing its new Amadeus reservation system, which enabled revenue management optimization by origin and destination rather than just an individual flight leg, accounting for connecting traffic. JetBlue says it doesn’t really need that (because few of its passengers connect). But it’s shopping for a new reservations system anyway.

New airplanes are more cost efficient, for sure, but can also help with revenues. United’s new B787-10s, for example, are the right planes for certain transcon and transatlantic routes. American is aggressively adding 787s. Delta is re-fleeting with twin-aisle A330-NEOs and A350s. Everyone except Allegiant is adding MAXs or NEOs. And the A220 is on a roll, entering service with Delta last week and winning big orders from JetBlue and David Neeleman’s new startup.

Also interesting are things carriers are doing with older planes, i.e., United turning 70-seaters into plusher 50-seaters. Will JetBlue take A321-NEO LRs for Europe? Yes, it seems, if it can get Heathrow slots. One final note about U.S. fleet strategy: Carriers haven’t been afraid to defer or cancel orders (i.e., United no longer wanting A350-1000s). They haven’t been shy about switching (Hawaiian dumped A330-NEOs in favor of B787s). And they’ve refrained from the biggest wide-bodies—no A380s or B747-8s, that’s for sure, but no B777-Xs yet either.

There’s a new appetite for growing in places where growing is physically difficult, in other words, at gate-constrained airports. Spirit, for one, is ready to move when gates become available. American’s single biggest revenue initiative is growing at new gates it will get in Dallas DFW, Charlotte and Washington DCA.

United focuses on it most, but it applies to American and Delta too: enhancing regional connectivity, especially at mid-continent hubs. It certainly seems to be working at hubs like Houston, Chicago and Denver. The idea: Put more two-class regional jets in small cities, creating new demand for other flights via hub connections.

But there’s a problem: Pilot scope clauses limit regional jet outsourcing, and one thing the Big Three will never do (for cost reasons) is fly regional jets with mainline pilots. Delta uses mainline pilots for B717s and A220s, which works well in many markets, but not the smallest of markets. United, for its part, wants pilots to accept scope clause changes.

U.S. airlines are achieving revenue growth by investing in better planes, better punctuality, better seats, better food, better lounges, better technology and so on. Anyone crammed in a middle seat on a densified plane might react with disbelief. And a growing chorus of antitrust scholars say the U.S. airline industry is too concentrated, citing poor service as a manifestation of consumer harm.

But it’s true: Even as airlines like Spirit choose to aggressively compete on price—evidence perhaps that the sector is not over-concentrated—others are spending enormously to compete on service. Showers in first class like Emirates? Not quite. But direct-aisle access, lie-flat seats? They’re now standard for premium fliers on American, Delta and United. Ditto for high-speed Wi-Fi, in all classes on most airlines.

The final point on revenues is that they really do respond to movements in costs. With a lag? Yes. But over-concentrated or not, the U.S. airline sector adheres to some measure of cost-plus pricing. When fuel prices remain depressed for long enough, fares will fall. And vice versa. They achieve this, more precisely, primarily through capacity moves—when fuel prices fall, airlines grow more quickly (because the unit-cost benefits of growth are more attractive when fuel is cheap), and fares fall in response to the additional supply of seats in the marketplace.

And… well… vice versa. The question now: Will Q1 fares and revenues fall in response to the late-2018 fuel price drop? Fuel prices, to be clear, have come up a bit in early 2019. Demand, meanwhile, is still super strong. And all those airline self-help revenue initiatives are still doing their part. There might yet be some revenue growth momentum left.

Editor’s Note: This article first appeared in the Feb. 11 edition of Skift Airline Weekly.

The Daily Newsletter

Our daily coverage of the global travel industry. Written by editors and analysts from across Skift’s brands.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: airline earnings, airline weekly, U.S. airlines

Photo credit: In the second and third quarters, not one major U.S. airline increased its margins year-over-year. But by the fourth quarter, a few—led by Spirit Airlines—did. 248108