Delta Air Lines Doesn't Want to Be Pigeonholed as a Transport Company

Skift Take

Is a major global airline a transportation company meant to shuttle passengers to their destinations on time? Or is it a consumer brand, like Apple or Starbucks, that connects with customers on a more emotional level?

Historically, most U.S. airlines have positioned themselves as transport experts, though some increase spending on customer experience and marketing as profits permit. But last week, at an investor day in New York, Delta's executives sought to persuade the financial community their business is less an airline and more a consumer brand with a deep (and potentially more lucrative) connection to customers.

"This is increasingly not an industrial transport brand," chief marketing officer Tim Mapes told analysts. "It is one that we ourselves view as a trusted consumer brand."

In another industry, that's normal talk. Visa isn't just a payments company, and while Starbucks has fine coffee, it's probably not tasty enough to justify its substantial price premium. But customers trust Starbucks, and they're not only willing to pay more for its products, often (erroneously) believing them to be superior than what corner coffee house serves, but they're also more open to sharing data with the company.

Unlike Starbucks, U.S. airlines generally haven't been respected by customers. Instead, many consumers love to complain about them, calling out airlines for service failures, cramped seats, new fees, and sometimes spotty on-time performance. Now, though, Delta may be breaking from the pack, allowing it to establish closer bonds with customers.

Delta isn't Visa, Apple or Starbucks yet. But a decade after merging with Northwest Airlines, Delta is inching closer to trusted brand status, something the U.S. airline industry hasn't seen in a long time, if ever.

"This is a step forward in the category collectively, and for Delta specifically," said Tom O'Toole, clinical professor of marketing at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University. "This is a real advance."

Wringing Revenue From Customers

O'Toole should know. Before joining Northwestern, he was chief marketing officer at United Airlines, guiding its brand positioning after it merged with Continental Airlines. He said all three major U.S. global airlines improved their marketing since returning to profitability after the financial collapse and fuel spike of a decade ago, but none so much as Delta, the first of three to merge with a big competitor, in 2008.

“The brand in some fundamental and sustainable ways is creating customer relationships that arguably can produce superior customer lifetime value,” he said.

Indeed, for Delta, this is not just a matter of semantics, which is probably why it shared its strategy with Wall Street. Customers who view airline travel as a commodity are more likely to search for the cheapest fare, eschewing an option if it costs $5 more. But passengers who trust a brand may pay more, while sharing more data. "The brands you love are likely to be brands you're more willing to give greater information to," Mapes said.

Attached consumers also more likely to buy into the airline's loyalty ecosystem, a big business for Delta and other U.S. airlines. American Express, which manages the airline's co-branded credit card, directly will contribute $3.4 billion to Delta's revenue this year, up from $1.9 billion as recently as 2009. (How much American Express pays Delta for each frequent flyer mile is a trade secret, but insiders say card companies pay between 1.25 and 1.5 cents, per mile.)

Delta likes American Express co-branded account holders for other reasons, too. Mapes told investors customers who have Delta’s co-branded credit card spend 11 percent more per ticket, on average, than customers who don’t.

“People pay more as they are in our program,” he said.

More engagement could lead to even more revenue, Mapes told analysts. As customers develop a deeper connection to a brand, he said, they’re more likely to open or respond to messages from it, opening more chances for Delta to sell ancillary products.

“Starbucks [may] e-mail you or text you and say, 'Last week you bought three lattes, if you buy a fourth one this week, you'll get blank,' right?,” he said. “It's the simplicity of that idea of pulling you through a curriculum.”

In a post Monday, analyst Brett Snyder, who blogs as Cranky Flier, noted customers who willingly participate in the airline's "curriculum" may no longer see it as a ruthless entity that wants to take as much of their money as possible. Even when they must pay more for a better experience, Snyder said, Delta's most loyal passengers still like the airline.

“Anyone can sell a ticket, and really, anybody can slap on a bag fee,” Snyder said. “What’s really hard, however, is finding a way to upsell people and have them still like you for it. Delta’s has been leading the charge in this area to the point that other airlines have become jealous.”

How Delta Got here

Delta didn't get so far ahead of its U.S. competition just by increasing its marketing spending or changing its brand positioning through traditional media strategies.

A lot of its success comes from its focus on customer experience and reliability. It has a better on-time rate than other large U.S. airlines, fewer flight cancellations, a more consistent onboard and airport product, well-regarded premium cabins, a functional digital strategy and a friendly, mostly non-union, workforce.

“They are not doing it primarily through brand marketing," O'Toole said. "They are doing it based on customer experience."

Other strategies also have helped it facilitate trust. Recently, Delta embarked on a strategy to turn younger customers into lifelong loyalists. And it knows these customers have different expectations than passengers in their 50s and 60s.

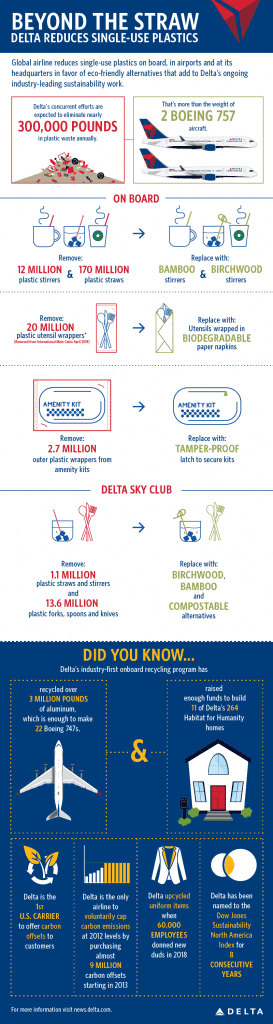

As it seeks to position the brand to make it attractive to the sub-40 set, this year Delta has prioritized diversity among its workforce, pulled a discount for the National Rifle Assocation, flown high school students for free to an anti-gun rally and announced it soon will stop using single-use plastic items, including stir sticks, wrappers, utensils and straws.

“Millennials are about 61 million people, $44 billion in spend,” Mapes said. “Increasingly, they're making decisions in ways that are very different than what an industrial transport company would focus on. They're making decisions that if a company mistreats its employees, they will actively switch from that brand. They will switch and buy more from someone they see as not only socially responsible but outspoken and actively engaged in the causes that are important to them.”

So far this year, Mapes claims this strategy is working, telling analysts the airline has measured a 38 percent increase in "intent to recommend" from its millennial customers.

Other customers are becoming more attached to the airline's brand, at least according to Mapes' preferred metrics. He told investors Delta is the only U.S. airline described in human terms during focus groups, with business travelers using words like, “caring” and “warm.”

A senior executive from least one competitor did not agree. JetBlue Airways has long advertised that it brings "humanity back to air travel," so Marty St. George, the airline's executive vice president for commercial, took to Twitter to push back on Mapes' claim.

He went with a one character response —a face emoticon with one raised eyebrow.