Skift Take

Travel is supposed to be the grand connector. Yet, whether consciously or not, the travel publishing world seems to be failing to seize a moment to champion what it always has championed — that travel helps reduce prejudice, bias, and bigotry.

Russia’s been in the news a lot lately —just not the travel news.

Normally, year-end “best of” annual travel lists – like Lonely Planet’s enduring Best in Travel series or the New York Times’ 52 Places to Go – give extra weight to destinations celebrating big anniversaries or hosting major world events. Both put Canada’s 150th birthday at No.1 in 2017, for instance, and each had Winter Olympics-host South Korea’s Winter Olympics in their list this year.

But in 2018, Russia is not getting love from publishers, which comes as a surprise since so much has been happening there. In 2014, Sochi hosted the Winter Olympics, and 2016 marked the centennial of the iconic Trans-Siberian Railway. In addition, this year 11 Russian cities are set to host the World Cup.

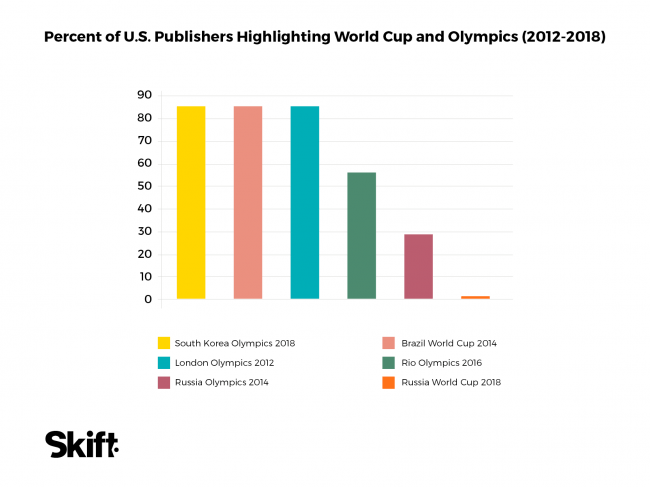

Yet none of eight major U.S.-based travel publishers Skift surveyed (see chart) picked Russia as a go-to place in 2018. And in 2014, during the Olympics, only two of eight —National Geographic Traveler and Travel & Leisure — picked Sochi as a must-visit destination.

Of course, a big event doesn’t necessarily ensure inclusion as a “best place to go.” But the Olympics and World Cup are really big — more than 21 million Americans tuned into the Sochi Olympics nightly, and about 3.2 billion worldwide watched the last World Cup.

The World Cup is a lot bigger deal than what’s happening in Malta, the recently-named the 2018 European Capital of Culture. Malta, however, was endorsed as a “place to go” by six of eight publishers.

Given the importance of the World Cup, it makes one wonder: Do U.S. travel publishers have a bias against Russia?

Note: Skift surveyed The New York Times, Lonely Planet, Conde Nast Traveler, Travel & Leisure, National Geographic Traveler, CNN, Afar and Frommer’s

What Publishers Say

Dan Saltzstein, an editor of The New York Times’ travel section, said by email the newspaper’s “52 Places to Go” list comes from “hundreds of pitches” from writers.

“Not every event gets a destination on the list,” he said. “We aim for a geographic and thematic diversity.”

Saltzstein noted the Times mentioned the World Cup in a sports event round-up for the year and said the newspaper is planning a last-minute travel guide for the World Cup. And beyond the curated lists, the Times’ travel section has covered Russia, too.

Russia last became a “place to go” for the Times in 2012, with the newspaper citing an update at the Bolshoi Theatre and a new Moscow sex shop for the country’s inclusion. Since then, the Times’ list has spanned the globe, including mentions of Azerbaijan, Zimbabwe, Switzerland (seven times), St Helena, the Falklands, Greenland, Serbia (twice), Republic of Congo (twice), Chile (five times) and Space. Even Alabama made consecutive editions, in 2017 and 2018.

Lonely Planet’s process for determining the “best in travel” starts similarly — with suggestions from staff and more than 200 freelance writers — but goes to an in-house panel of judges to debate and vote on winners and, a process that should ensure there are no gaps. (Disclaimer: Robert Reid, writer of this story, was on the panel from 2009-2014.)

This year, seven of the 10 countries Lonely Planet picked were celebrating milestone birthdays or hosting major events. South Korea was No. 2. But, as with the Sochi Olympics four years ago, Lonely Planet did not pick Russia.

“This year we felt the other 10 countries that made the list had a stronger offering,” Dora Ball, a London-based commissioning editor for Lonely Planet, said by email.

“Particularly when we considered that a number of the reasons for Russia’s nomination had been covered the previous year in our coverage of Moscow as a top 10 city to visit in 2017.”

But Russia is Difficult

While the editors may be playing coy, one possible reason for a possible Russian “blockade” — subconsciously or otherwise – is that it’s never been an easy country to visit.

Russia’s visa process remains one of the world’s most complicated, and savvy travelers with extra money often use an outside agency to obtain one. A visa costs $144 for a single-entry visit for American passport holders.

Of course, visiting the Republic of Congo is an expensive hassle too. Unlike with Russia, there are no nonstop flights from the United States, and the country charges $200 for a visa that takes three months to process. Yet The Times has plugged the Congo twice since 2013, and Lonely Planet once.

Brazil’s visa, at $160, is also more costly than Russia’s, and requires applicants to send passports to one of 10 U.S. consulates well before a trip. But the eight publishers surveyed collectively put Brazil, host of the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics, in their top destinations 10 times over those two years. This suggests Russia’s tricky visa process isn’t the deal-breaker.

Then again, one could argue the best case against recommending travel to Russia can be found in the U.S. State Department’s travel warning.

The State Department ranks its travel advisories from 1 to 4. The strongest alerts are “4,” or “do not travel,” a ranking reserved for the most unstable and war-torn nations, such as Afghanistan, North Korea, Syria, and Yemen. The next ranking of “3,” or “reconsider travel,” includes Sudan, Nigeria, Turkey, Venezuela, and Russia.

In the warning, Russia is flagged for incidents of “terrorism and harassment,” specifically in the Crimea and the Caucasus areas, including Chechnya. The UK’s Foreign Office warns against travel specifically to this region too, though it notes there is “no indication that British nationals or interests have been specific targets” of terrorist activities.

The U.S. ranking may be too heavy-handed. The area identified in the warning comprises 75,800 square miles, or 1.15 percent of Russia, and does not include any World Cup locations. A traveler who skipped Moscow solely because of its proximity to the Chechen capital of Grozny, 1,152 miles away, is as foolish as one who cancels a trip to Chicago because of a 2016 nightclub shooting in Orlando.

It’s a grisly business to compare murders and acts of terrorism, but statistically Russia is no more risky for visitors than many places in the United States or Western Europe. Most of them have a “1” ranking from the State Department.

Is Travel a Political Act?

No one is saying it, but it’s certainly possible Russia has been left off these “best places to go” lists because of the likelihood the Kremlin interfered with the 2016 U.S. elections. It’s beginning to feel like a growing Cold War redux.

In the past, the travel community has veered clear of political entanglements, but it has sometimes penalized governments and policies with unofficial “travel boycotts.” It happened in Burma, now known as Myanmar, when the democratically elected leader Aung San Suu Kyi was put under house arrest, and South Africa during apartheid.

There is no evident travel boycott of Russia today, and that’s as it should be. Still, there is an issue. Russia and Russians have long been hit with negative stereotypes, and that affects how outsiders view the country.

A 2017 Pew Research Center study found only three countries where populations had a favorable view towards Russia: Greece, the Philippines and Vietnam.

It’s not likely that Americans – including writers and editors – fully grasp the extent the damage that decades’ worth of negative coverage has made to influence our general perception of a one-time ally.

It seems different for China, which likewise hasn’t always had a chummy record with the United States, but still is favored by travel media. Lonely Planet has included China four times in their past five “Best in Travel” lists. And the Times has featured China 12 times since 2012, making it a more popular choice than France or Italy (each with 11 mentions).

Meanwhile, Russia is all but shut-out. Among the eight publishers surveyed, Russia garnered five recommendations — two by National Geographic Traveler — of 1,005 total “places to go” picks in the last five years.

It’s a shame because travel isn’t really about government or politics.

In an oft-quoted essay from 2000 called “Why We Travel,” Pico Iyer claims travel is about “seeing the world clearly, and yet feeling it truly.” We don’t travel to a government, this common argument goes, but for person-to-person encounters that break down barriers between different peoples, languages, religions, races, clothing types, diets, or even whether they spell “traveler” with one or two L’s.

Travel publishing regularly echoes this sentiment. Rick Steves wrote a book and created a documentary about going to Iran called Travel is a Political Act. A Travel & Leisure essay defending “why we travel” begins in a Soviet car in 1989. And Paul Brady of Conde Nast Traveler says it’s the very uncertainties in the world that make it “the time to travel.”

I’ve spent a half year over four trips in Russia, twice taken the Trans-Siberian railway to Vladivostok, and lived and studied in Moscow during college. Most Russians you meet don’t want to be judged by their leaders, just as most Americans don’t care be judged by theirs. And Russians, I’ve come to learn, can rank amongst the world’s cuddliest sweethearts.

For example, many get positively giddy over finding mushrooms, which they charmingly “collect” (sobirat) rather than “pick.” If you befriend a local, they’ll take you on very long walks, and often gift you a book. No country I’ve seen has more flower shops. Last year, I visited a hole-in-the-wall rock club down a dark, un-signed St Petersburg alley, and a rat scurried past as I approached. Inside, indie rockers had set out colorful blankets on a spotless floor to sit and watch a dreadlocked musician wail over an acoustic guitar.

These are important images that don’t get picked up outside Russia much.

Travel is supposed to be the grand connector. Yet, whether consciously or not, the travel publishing world seems to be failing to seize a moment to champion what it always has championed — that travel helps reduce prejudice, bias, and bigotry.

The Daily Newsletter

Our daily coverage of the global travel industry. Written by editors and analysts from across Skift’s brands.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: russia, tourism, travel media

Photo credit: Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyani (center) rode to mark the launch of a city bike program in 2013. Moscow Department for Transport and Road Infrastructure