Channel Shock: The Future of Travel Distribution

Skift Take

The travel industry is always fixated on what’s new and sexy.

Whether it’s booking a hotel using Amazon Alexa, or checking your Priceline booking from your Apple Watch, we tend to focus on incremental improvements to how consumers book and experience their travel. Yet, the main system that sits underneath the snazzy interfaces, which actually connects hotels and airlines with online booking sites and travel agents, has its roots in a handful companies originally founded by U.S. and European airlines.

If you’re not deeply entrenched in the fields of travel distribution and technology, you may not know that the same type of technology has been used since the 1960s to handle transactions between travel providers like airlines and the companies that purchase travel for travelers.

After general aviation began to surge following World War II, orders for air tickets were placed by phone. Digital tools were developed to automate how airlines track and sell their inventory beginning in the 1960s.

These systems, commonly known as the global distribution systems (GDS), have done much to determine the shape of the global travel marketplace and continue to shape it to this day.

This technology completely transformed how people traveled beginning in the late 1970s, once travel agent terminals were rolled out to allow direct access to these systems; travel agents could place remote bookings from their offices, streamlining the booking process as global air travel began to expand.

Things have changed in the last two decades. As the Internet democratized travel booking, allowing consumers to search online, travel agents have been marginalized when it comes to leisure travel in the U.S. Travel agents still play a stronger role in other parts of the world. But online travel agencies and travel management companies still place bookings using GDS platforms, since they offer the most comprehensive collection of travel inventory across the globe.

Likewise, most travel providers need to remain part of a global distribution system for consumers and business travelers to easily find and book their products.

Today, four companies dominate the travel distribution landscape: Amadeus, Travelport, China’s TravelSky, and Sabre, the original company to develop this technology when it was a division of American Airlines.

Could this change one day? Do new technologies, like direct connections between airlines and travel agencies or consumers, pose a threat to the dominant role played by global distribution system providers in the travel ecosystem?

Skift spoke to executives at the world’s largest travel distribution technology companies about how they are moving forward in the marketplace, along with leaders at smaller technology companies providing solutions for areas where global distribution system technology has lagged.

History of global distribution systems

In the beginning, airlines developed their own technology to inventory and sell their flights. The Semi Automated Business Research Environment, Sabre for short, entered operation in 1963 for American Airlines through a partnership with IBM. The system essentially created a digital database of flights that could be reserved by phone.

In 1976, Sabre debuted terminals designed for travel agents to remotely access airline reservation databases without needing to call in. This helped revolutionize the ability of travel agents to shop for flights and empowered them to further expand their role as an intermediary in the travel industry.

Travel agents could search the database for flights meeting their clients' needs, and book them remotely. While complicated, using unintuitive symbols and nomenclature, these systems became commonplace around the U.S. and Europe. Many of these seemingly arcane formats and scripts are still used today.

“Every airline decided to have their own reservation system but imagine from the point of view of a consumer or even a travel agency, if you just wanted to do a comparison, that comparison was very cumbersome,” said Decius Valmorbida, senior vice president of travel channels at Amadeus. “So from a resources point of view, you have similar competitors, similar airlines that have infrastructure in parallel. So the creation of the GDS was to solve this issue which is with a single infrastructure, you can serve multiple airlines and therefore that brings the cost advantage and a cost efficiency to the industry so that's good. It brings tremendous benefits to travelers and travel agencies because it provides easy comparison and an environment that is tailored for the consumer to make their choices.”

Sabre itself was spun off from American Airlines in 2000 into a public company, then acquired by a private equity group in 2007, only to go public once more in 2014.

Travelport got its start as United Airlines’ Apollo and Galileo systems in the early 1970s, essentially a competitor of Sabre, and evolved over time into a full-fledged travel technology company that became independent in 2006.

Amadeus was founded in 1987 by a group of European airlines including Air France and Lufthansa, creating a European challenger to the U.S. distribution systems and it went public in late 1999.

The three major global distribution systems — Amadeus, Sabre and Travelport — are all public companies today.

Regulation in both the U.S. and Europe for a time played a major role in positioning these systems as something of, however flawed, an impartial marketplace in an ecosystem that is increasingly defined by competition and complexity.

Beginning in 1984, U.S. global distribution systems were highly regulated, the result of a growing global travel industry and the effects of the major players that sold travel products also controlling the systems for distributing them.

This led to the distribution companies listing products by preferred partners at the top of search results, causing travel agents to book fares for clients that appeared superior but often were not.

The U.S. Department of Transportation effectively deregulated the global distribution systems in 2004; now that the companies had been separated from the airlines which had founded them, less strict regulation was necessary to ensure a competitive travel selling marketplace.

“Any display bias by the systems would not be comparable to the practice of grocery stores selling preferential shelf positions to their suppliers,” states the deregulation ruling in the 2004 Federal Register. “Unlike the grocery store shelf, which the shopper sees and can easily scan, the traveler never sees the system display used by a travel agent, and systems can create display bias that obscures the service alternatives to a much greater extent than the shelf position used by grocery store suppliers. Airlines would be willing to buy bias because it would be effective, and its effectiveness means it is likely that a significant number of consumers will be booked on inferior services when other services would better meet their needs.”

In the end, rules prohibiting display bias were removed. Since the bulk of airlines were using the global distribution systems to sell their tickets, a rule against bias had become unnecessary in the view of the U.S. government. Since these systems now had content from virtually all the major airlines, the search results basically spoke for themselves and there was no need to essentially trick agents into booking less attractive flights. This ruling created the landscape that exists today.

However, agencies still can bias their own displays to favor preferred partners. Travel agents book with bias, usually depending on airlines they have preferred agreements with that end up earning them override payments if they reach a certain level of volume each year.

Concerns were raised once again in 2011 about display bias, but bias in the GDS was seen by the government as less pernicious than similar behavior conducted by online travel agencies in an attempt to present consumers with certain flights they receive money to promote above more suitable flights.

New rules for the global distribution systems were not adopted following the warning from the Department of Transportation, but guidance was given on the type of competitive behavior it would like to see in the marketplace.

In the end, consumers and travel companies ended up with three giant companies controlling the majority of how air tickets are listed and sold.

“I think of it a lot like an advertising network basically,” said Wade Jones, president of Sabre Travel Network. “We're the connective tissue between the buyers and sellers. I will say oftentimes people will want to diminish the value of the GDS but there's so much more to it because in the beginning it was pretty simple...

“The other thing, when people are provocative around saying things like, ‘It's just a pipe. You don't actually have any customers, the agencies have the customers and the corporate. You don't actually have any inventory because that comes from the suppliers.’ I think we're in good company because you look at the likes of Uber, which is the largest transportation company in the world and they don't own any cars. Airbnb is the same thing, largest hospitality company and they don't own any properties. Facebook's the largest media company in the world and they don't create any of their own content.”

Today, the race is on to crack the Asia-Pacific market, which has been strongly resistant to the influence of these companies. In 2015, Sabre acquired leading Singapore-based global distribution system Abacus, which was created by a consortium of Asian airlines for much the same reason as the original U.S. global distribution systems.

China, the world’s fastest growing travel market, relaxed restrictions on foreign travel distribution companies entering the market five years ago. It had forced its travel agents to use TravelSky, a China-based global distribution system, and Travelport was one of the first North American companies to partner with TravelSky. Africa is another hotbed of investment as its countries become more connected by air travel.

Current Landscape

Today, three main players still dominate the North American and European global travel distribution system landscape: Amadeus, Sabre, and Travelport. Amadeus is the largest player in the travel agent air booking market, with a self-reported 43.5 percent market share in Q1 2017, followed closely by Sabre’s 36.3 percent.

They also offer travel technology services like airline information technology products, travel agent interfaces for connecting to their global distribution system network, and revenue management tools for hotels and airlines to help price and merchandize their products.

These three companies make the bulk of their money off air bookings; in particular, they earn huge margins by charging license fees, service fees, and transaction fees for bookings and access to their networks. Hotel bookings comprise a small portion of their booking business, about 10 percent, due to the complexity and fragmentation in the global hotel distribution marketplace.

| Air Bookings | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amadeus | 535,000,000 | 505,000,000 | 467,000,000 | 443,000,000 | 417,000,000 |

| Sabre | 445,050,000 | 384,309,000 | 321,962,000 | 314,275,000 | 326,175,000 |

| Non-Air Bookings | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amadeus | 60,000,000 | 61,000,000 | 59,000,000 | 59,000,000 | 61,000,000 |

| Sabre | 60,421,000 | 58,414,000 | 54,122,000 | 53,503,000 | 53,669,000 |

Business for the global distribution system companies is a mixed bag so far In 2017. Despite facing headwinds, particularly due to the uncertain state of travel in Europe, Amadeus grew revenue and profit in the first half of 2017. The company is working on a reservation system solution for InterContinental Hotels Group, which is set to launch later this year, and slightly grew its share of the overall air booking market.

Sabre, under new CEO Sean Menke, slashed 900 jobs last week in an attempt to tighten its belt and focus on its most profitable products, while European bookings were weak in 2017 following Alitalia and Air Berlin's recent financial problems.

Travelport experienced a slight growth in revenue year-over-year in the second quarter of 2017, and re-signed Delta Air Lines to its platform in a move that bodes well for the rest of the year.

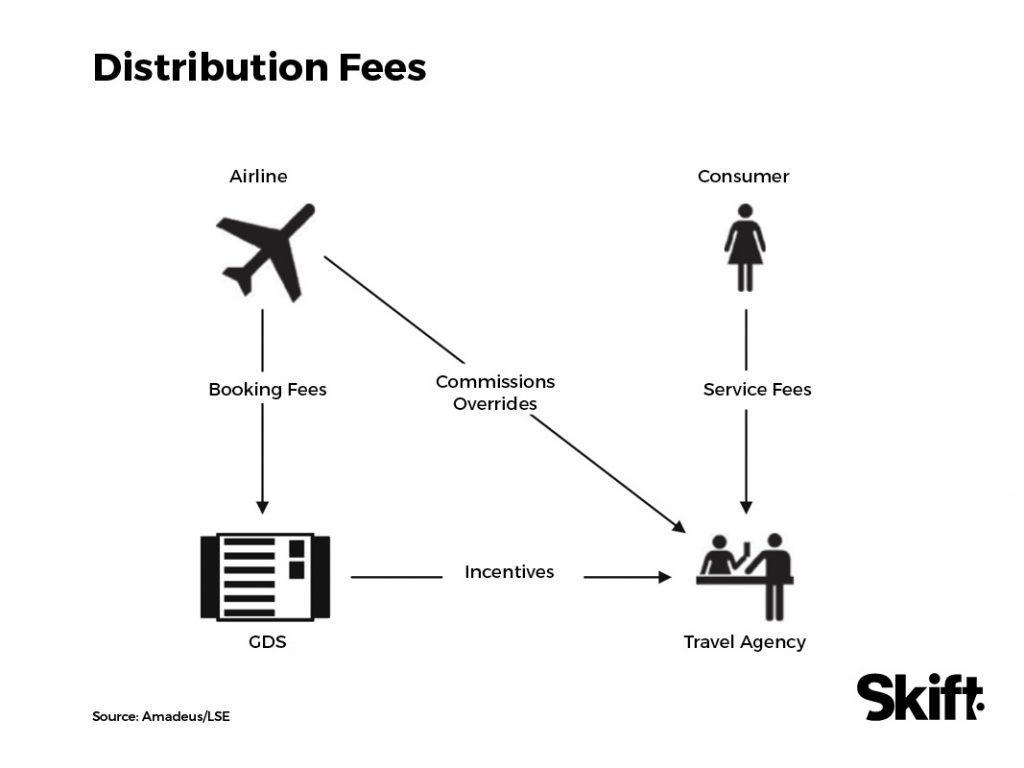

The key piece to the continued dominance of global distribution systems is the cost they charge per transaction. Fees for an air booking are usually between 2 and 4 percent of a ticket, and about 20 percent for a hotel booking. Business models differ from company to company for travel providers, travel agents, reservation systems, and other areas.

In other words, for a percentage of a booking’s price, an airline receives access to a global network of travel sellers ranging from travel agents to online travel agencies. Airlines also pay for software-as-a-service access along with other fees for implementing system access and consulting on various issues. The bookings made through these systems tend to be more complex, and expensive, than simple flights a consumer can book for themselves online, granting a higher fee to the global distribution sytem than a mere flight would.

These fees, argue the global distribution system companies, represent a sum much lower than it would take to build a new distribution system or perform the marketing needed to encourage the bulk of travelers to book directly on an airline website. While ostensibly a small percentage for airlines to pay, it adds up when a billion seats are being booked each year, and includes other payments for access to the systems and other services.

Sabre lays out this dynamic from its perspective in the 2013 S-1 filing it made before it went public for the second time.

“Travel suppliers incur a booking fee which is, on average, only approximately two percent of the value of the booking by using the GDS,” states the filing. “Therefore, the revenue generated through the GDS leads to a return on investment that is attractive compared to the incremental cost, in part because many of the tickets sold on the GDS platform are more expensive long-haul and business travel tickets (particularly those originating outside the home country of the airline) as well as tickets with additional booking complexity (e.g., multiple airline itineraries). These platforms also offer a particularly cost-effective means of accessing markets where a travel supplier’s brand is less recognized by using local travel agencies to reach end consumers.”

In the last decade-plus, the airlines seemingly blew their chance to break away from the global distribution systems. American Airlines first experimented with direct-connect technology in the mid-2000s, allowing online booking sites and some travel management companies to access American's inventory, and now almost every airline has an API available for direct searching and booking.

It’s complex technically to actually search for a fare using a global distribution system; fare data has to be loaded into a database maintained by ATPCO and SITA while scheduling data is located in another system, OAG. And the system has to finally check with the airlines themselves to see if a seat is available. It can take awhile so airlines can't update fare prices as often as they would like. There are dozens of other systems and solutions out there that allow airlines to manage this complexity.

Yet, a widespread shift away from global distribution system bookings never happened — despite years of prognostications that the end was drawing near.

"GDS fees paid by airlines were over $7 billion last year and global inducements to agents were over $3 billion dollars," said Al Lenza, a veteran airline industry consultant. "All the $3 billion flows through back to the travel agents and corporate accounts, and there is no interest in participating in a reduction of that $3 billion.

"Whenever Farelogix is doing a direct connect or Concur has a new technology, the first thing that the intermediaries do is say that it's inefficient and that's gonna raise [an airline's] costs. But Sabre is nothing more than 400 direct connects. The real reason is the $3 billion dollars. [Agencies] don't want to give it up and the GDS in essence provides a protection for those revenue streams by holding a gun to the airline. The gun is: If you try to pull out because you don't like the pricing, the revenue disappears if you’re not in the GDS, and especially if you are an airline that has always been in the GDS."

There's also the matter of so-called full-content agreements, in which an airline agrees to place all fares available through other channels on the global distribution systems, as well. Airlines don't like this, because it affects their ability to market and merchandise, but often have to play ball to receive better terms from a global distribution system provider.

While there’s been a dramatic shift in how consumers book travel in recent years, the global distribution system providers are still growing their top lines.

| Net Revenue in Millions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue 2016 | Revenue 2015 | Revenue 2014 | |

| Amadeus | $5,259.9 | $4,601.3 | $4,019.3 |

| Sabre | $3,373.4 | $2,960.9 | $2,631.4 |

| Travelport | $2,351.4 | $2,221 | $2,148.2 |

Amadeus has perhaps focused the most on the airline information technology space, hoping to broaden its product offerings and stay relevant as a travel technology company beyond its stature as a global distribution system provider. Its early 2016 acquisition of Navitaire, which provides merchandising and reservations services aimed at low-cost carriers, shows this commitment, while the other global distribution system companies have also introduced more robust airline IT capabilities in recent years.

Payments also comprise a growth area, along with dashboards for travel agencies that incorporate rich content.

| Non-Distribution Revenue in Millions | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amadeus | $1,820.3 | $1,381.7 | $1,132.4 |

| Sabre | $1,019.3 | $872.1 | |

| Travelport | $120.9 | $125.9 | $117.5 |

“What we see is growing interest and usage of single-use virtual cards,” said Jason Clarke, senior vice president and managing director of agency commerce for Travelport. “We see that will continue to grow as we look out, certainly in the next few years. I think there'll be more opportunity in the payment spaces as we move forward with different economic models and different content models that are naturally out there too."

Corporate travel plays a major role in the ecosystem. Travel management companies receive a fee for placing bookings through a global distribution system. Airlines pay the global distribution systems for bookings and also give large override payments to the travel management companies based on the volume of flights they sell. In this model, every player is incentivized to continue to use the global distribution systems — except the airlines.

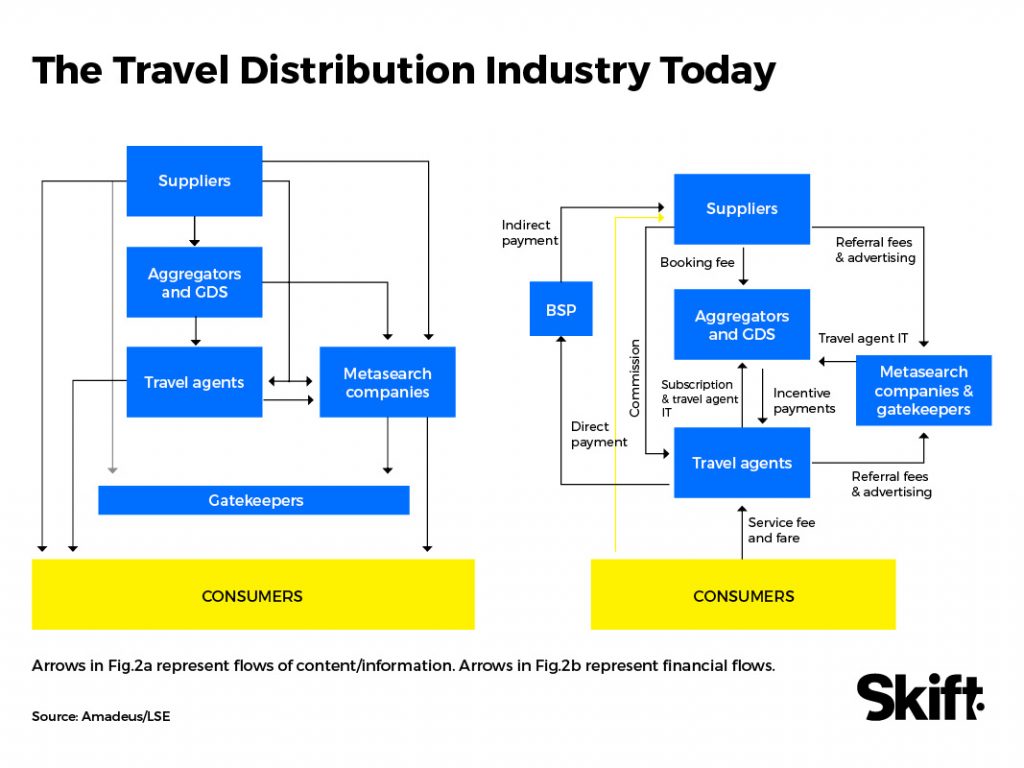

There is also the matter of disruption from relatively new industry players, ranging from online travel agencies to metasearch sites and even Google or Facebook.

“If the GDS fits from a technology point of view, do we have newer technology available in the market that could do a better job than the GDS?” asked Valmorbida “Do you need an intermediary at all? Do you still need that aggregation role and why an aggregation role is really needed? Maybe there are more modern ways of doing that. These are the questions the marketplace is raising and these are the questions that I believe we have answers for. We're still quite optimistic that there's a bright future because the very essence of why we're here continues to exist.”

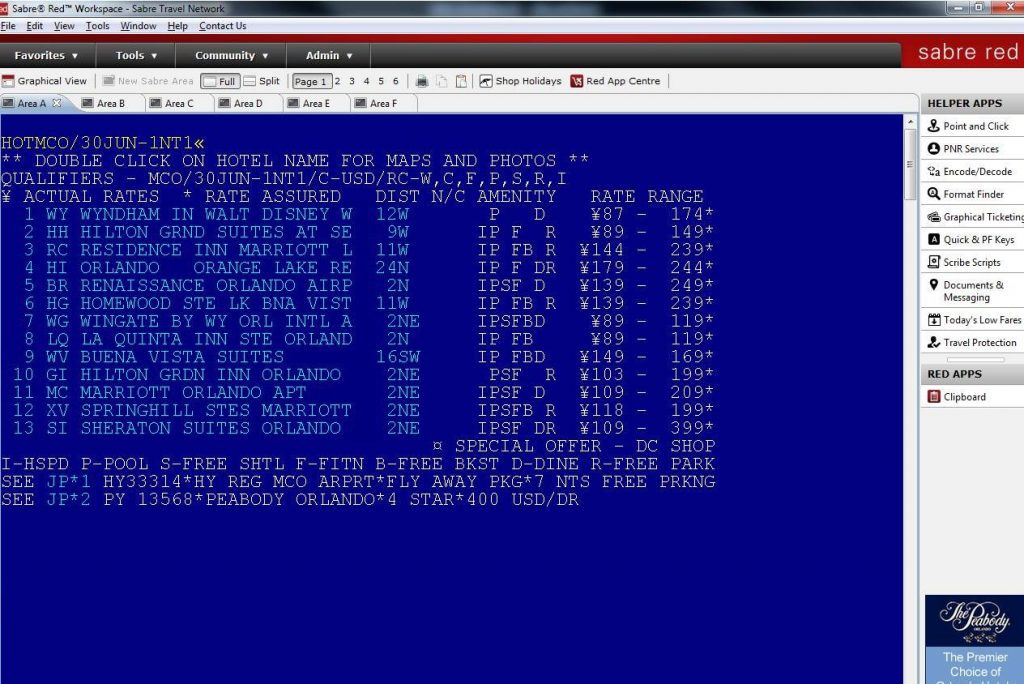

Relatively new travel agent desktops like Sabre Red, which sidestep the arcane language of traditional global distribution screens by using a graphical user interface, also show how important simplifying these tools are to younger travel agents who might balk at using symbols and text commands to search and book flights as older agents age out of the workforce.

Recent consumer trends bear out how the wider travel ecosystem will continue to shift in coming years. Just 11 percent of the U.S. travelers polled for MMGY Global’s 2017 Portrait of American Travelers used a travel agent in 2017, down from 15 percent in 2016. More than half of travelers are booking their air travel directly through an airline’s website or mobile app, while a third do so through an online travel agency.

The report also found that four in 10 U.S. travelers consider search engine results when making reservations.

"Google is beginning to dominate the travel planning process with 40 percent of travelers telling us they are using the search engine, making it the most popular website for Americans' travel planning,” said Steve Cohen, vice president of insights at MMGY Global. “It's especially popular among millennials, including millennial families, couples and singles. Google's predictive capabilities have made it an integral part of nearly every stage of the planning process.”

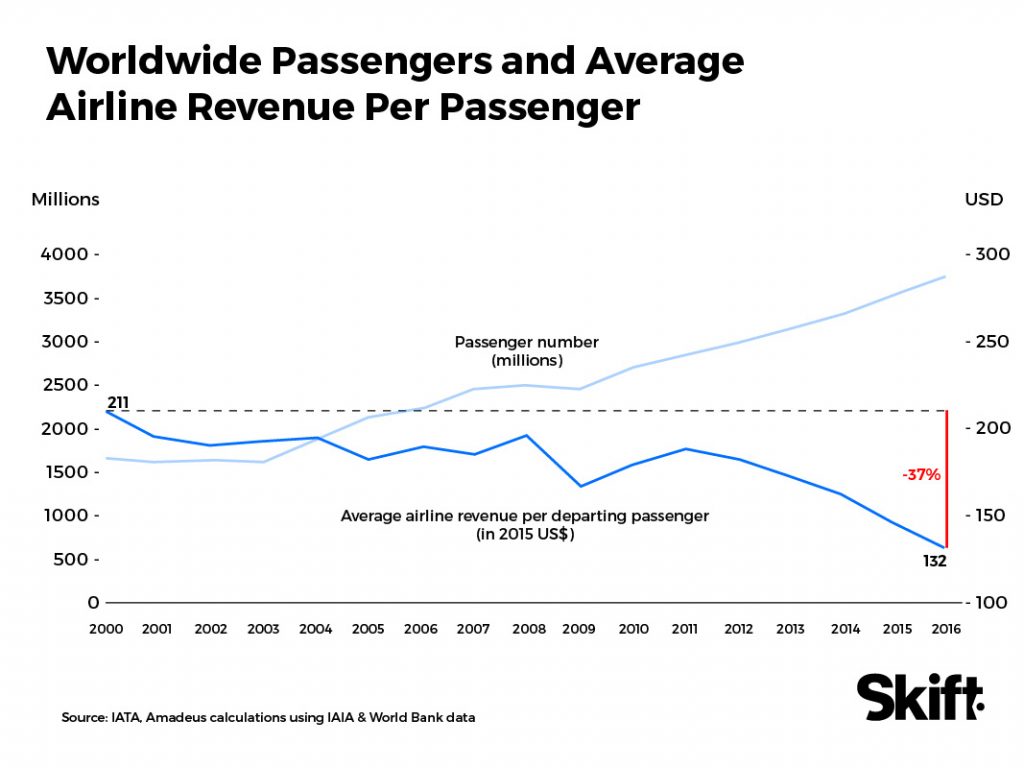

Based on consumer behavior, therefore, disintermediation could be the wave of the future. A recent report from the London School of Economics and Amadeus posits how these trends will affect the world’s major air carriers.

“While direct distribution can be effective for [full-service carriers] with strong brands in home markets, reaching consumers in international markets requires global networks provided either by GDSs and travel agents or by gatekeepers and metasearchers,” reads the report. “Big brand airlines could expand global direct sales in collaboration with gatekeepers such as Google and Facebook by paying higher fees for advertising and traffic acquisition. However, the power of the airlines to negotiate will decrease as the search control of gatekeepers increases. At the same time, smaller [full-service carriers] will need to rely on the transparent comparisons provided by GDSs to compete effectively.”

Backlash Against Global Distribution Systems

European airlines over the last few years have perhaps been most active in exploring distribution models outside the global distribution systems. Lufthansa placed a surcharge (about $16) on global distribution system transactions made by travel agencies in 2015 in an attempt to shift bookings to other channels. British Airways added a similar fee (about $11 per leg of a trip) earlier this year on bookings made through Sabre, Amadeus, or Travelport. These airlines are, for the most part, looking to reduce their distribution costs.

"Once an airline is passing along a GDS surcharge, then all of a sudden if the GDS raises the airline's prices the cost goes up [for flyers too]," said Lenza. "It's easier to be in the system than confront and battle to the death and be in the system [anyway]. You're better off paying more. You hope that the market keeps you as you build tools to be efficient for people to behave, Clearly Lufthansa moved a little faster than they needed to, but it seems they're gaining ground on interfacing with third parties."

There’s also the matter of disputes between certain airlines and the global distribution systems. The evidence in a lawsuit leveled by US Airways against Sabre shows that different airlines pay different transaction fees, based on other aspects of their contracts with the global distribution system. Reporting on the trial by The Company Dime showed that airlines like Southwest Airlines paid close to $2 less than Continental Airlines (now United) or US Airways (now American) did in 2010.

Southwest Airlines, which has pursued mostly a direct strategy to consumers over the years, chose to provide Sabre with a low ability to be booked, causing many travel agents to book Southwest flights directly online or through workarounds, and recently moved to Amadeus’ Altéa platform for both domestic and international reservations.

Other information contained in the court documents shows that online travel agencies and travel management companies often rely on one global distribution system for the majority of their bookings, showing the market-shaping ability and staying power of the agreements between these companies.

It’s no wonder some airlines have considered ways to wrangle better terms from the global distribution systems or have tried to move away from them to save on costs.

Hotels represent a small portion of distribution revenue for the distribution system companies, about 10 percent. There are many challenges in the hotel market for the global distribution systems, particularly the fragmentation of independent hotels and small chains, and the costs they impose on a booking, around 20 percent compared to two percent for air bookings.

Part of this is simply the difference in business models between airlines and hotels; airlines want each plane full, whereas a successful hotel has 60 or 65 percent of its rooms sold each night. This has ramifications for merchandising through a channel with transaction fees. Hotels also have different target markets; a 12-room lodge doesn’t need the distribution access that a 300-room business hotel does.

At the same time, this fragmentation poses a problem to travel agents, since it can be hard to find hotels in areas your client may be traveling to.

“Content is king, and if you look at the online travel agents that we're working with, they're very diverse and they have a massive range of hotels that they all connect to,” said Jason Lewis-Purcell, vice president of GDS for Siteminder, which provides transaction and revenue management solutions to hotels. “The GDS suffers [compared to online travel agencies] because it doesn't have a variety of content. It is really mainly four star-plus hotels that are on there. If you look at the travel management company market, the big guys like American Express and Carlson Wagonlit, their clients are usually quite high-end so they can service them. But when you come to these consortia markets where it is independent agents coming together, and it is really important that they don't lose clients, they need to be able to find that client accommodations along with their airfare. And that is where they suffer because they can't find accommodation on the GDS in every single destination that they need to.”

There are plenty of startups working to develop new solutions to the distribution problem areas, trying to ease the pain often created by the reliance on global distribution systems. We'll take a look at some of them later in this story.

Supplier Shock

Perhaps the most significant dynamic for travel companies selling products through the global distribution systems is whether the costs they pay for selling on the channel are worth it. For most airlines, it is. Others, particularly many low-cost carriers, sell directly or through direct-connects with online travel agencies to avoid these costs.

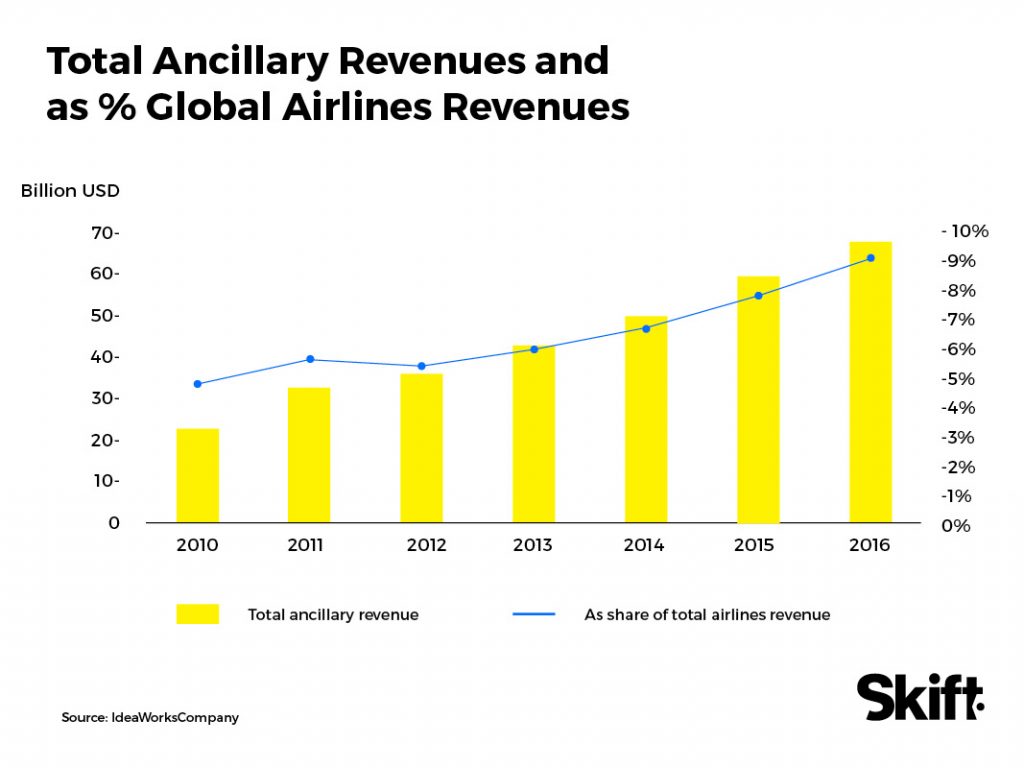

Complicating this is the importance of revenue management and add-ons to airlines and hotel companies.

The airline industry has been lurching forward towards adopting the International Air Transport Association’s New Distribution Capability paradigm for years, which essentially simplifies transactions between different members of the ecosystem by using XML coding language and allows for selling ancillary products like seat upgrades.

Yet, because airlines don’t have to use this technology, individual airlines have adopted it at a different pace. The rise of merchandising and ancillary products, however, has coincided with the adoption of this relatively new IATA standard. Traditional global distribution systems haven’t previously allowed for much customization in this area, being hampered by limitations in their fare basis code systems.

Today, they do offer new technology to enable this kind of customization and revenue management, but there is wide disagreement about how nimble this technology is.

“What I found in joining Sabre was that there was a lot of friction between the suppliers of travel and the GDS,” said Sabre’s Jones. “I thought it was really important for us to be reduce that friction and a really important part of that was making sure that we could present our supplier partners' brands and their products and good and services in a consistent way so that we can talk to them about optimizing their marketing across all channels. You're having then a distribution discussion versus a direct or an indirect.

“I do think that the lack of capability of the GDS probably drove suppliers to try to shift their customer acquisition to the direct channel. So as we build out our capabilities and have a reasonable cost of distribution, combined with the fact that the traveler that is acquired through the indirect channel tends to travel more frequently and buy higher priced tickets. Once you solve for that grand experience in the indirect channel, I think you can reduce friction with the suppliers and that's been a really important component of our product landscape and our roadmap.”

The emergence of branded fares and ancillaries has led the global distribution system companies to play catch up when compared to what airlines can offer through their websites or call centers. This has perhaps led to another opening in the marketplace akin to the mid-2000s.

Airlines are hesitant, however, to pay a global distribution system a cut of each ancillary transaction like they do for bookings; it makes little sense to subject this new revenue stream to the same model that has held them back with respect to merchandising fares. It also allows more advanced and comprehensive marketing and merchandising, based on the data each airline has, if these components are sold through direct channels.

There are also multiple tiers to the New Distribution Capability standard; while most airlines have implemented some aspects from level one, there are three levels of certification available to airlines and travel sellers. Only a handful of companies offer full level three capability.

One of the challenges with the standard is that while it represents a new one for airline transactions, using XML, airlines aren’t required to implement any or all of them. This has led to some airlines, like American Airlines, leading the way on integration, while others have lagged behind for a variety of reasons.

“[It was a mistake for GDSs to] not embrace the concept of NDC early,” said Jim Davidson, CEO of Farelogix, which helps facilitate connections between travel sellers and airlines. “By the time NDC was introduced to the market, it was clear that the existing airline connectivity to the GDSs would not scale or accommodate airline demand for differentiation. Again, the GDSs dug in hard early to fight any change in distribution technology and connectivity, which over time will cost the GDSs significantly as they are either bypassed or made less relevant by new commercial and distribution models. They could have championed this and managed its development, rather than losing total control of it.”

A Different Path

American Airlines announced in June that it had received New Distribution Capability level three certification, allowing it to operate with the same level of complexity when merchandizing through global distribution system channels as offerings received on its direct channel. This is big for corporate travel, allowing the airline to sell ancillaries and bundles through corporate booking tools. None of the big three distribution companies, however, offer New Distribution Capability level three capabilities (Sabre remains level one).

A little-known element of American Airlines’ strategy could be the most consequential moving forward. Some 20 years ago, airlines stopped paying commissions to travel agencies on air tickets. This thoroughly disrupted the travel agency community, and it still has never really recovered; many agencies have moved to a service fee-based model instead of relying solely on commissions or overrides, but the damage helped essentially gut the industry in the U.S.

Under American Airlines’ new distribution program, however, agencies placing a booking directly or through an intermediary using New Distribution Capability level three will receive a $2 payment per segment. This nominally represents the return of a commission model to agency air sales.

The goal is not only to incentivize agencies to use the technology standard, but to help spur innovation in the space. Agencies can give a piece of the commission to their technology provider, giving an incentive to smaller companies that they wouldn’t normally receive in the distribution space. If other airlines follow American Airlines and eventually offer a similar commission, innovation and disruption could follow.

“The reality is the airline industry doesn’t move very quickly when it comes to distribution,” said an airline distribution executive. “Let’s imagine American Airlines is not the last carrier to go down this path and some others decide they want to offer an financial incentive. This is something that could be potentially problematic for the GDSs. The GDSs charge a flat fee for every booking and pay a different amount to travel agents.

“For the vast majority of small or medium size agencies, this is an opportunity to earn something whereas they don’t earn something today. A lot of the incentives for big agencies are not there for small and medium agencies, so they will become a target. Small or medium agencies start taking up these offers, and GDSs lose the ability to cross subsidize bookings.”

A widespread return to airlines incentivizing agencies for bookings instead of just commission overrides could hit harshly against the bottom line of global distribution system companies; if less money comes in from airlines using the global distribution system platform, there will be less money to spend to encourage travel management companies to place bookings through distribution systems, potentially shrinking booking volume in the process.

Global distribution system executives say that despite the apparent battle between direct and indirect channels, airlines will eventually adopt an approach of offering the same products across all channels, much like in traditional retailing.

“We feel that with a process of maturity, airlines will come to realize that being on every channel and having a price transparency across channels is the best option,” said Amadeus’ Valmorbida. “We have seen other customers who applied channel discrimination in the past understand that trying to influence the behavior of consumers is a costly exercise and sometimes a fruitless exercise, because customers have a lot of choice...

“That's the typical behavior we see in retail or in other industries as well. The fashion industry, telecom industry, consumer goods industry, we see a number of players where you end up pricing a PC, a phone, and mobile phone the same price across every channel even though you know that different channels have different costs but it's the best way to achieve a broad range of distribution and going for your operational efficiency.”

With their dominant position in the marketplace, however, it of course benefits the distribution systems to have airlines adopt an omni-channel approach. Buying complex airfares, also, isn’t the same as buying a gallon of milk (whole, skim, or one percent?) from the supermarket or a pair of socks from Amazon. These travel products aren’t just commodities you can get anywhere, but experiences for consumers or business travelers.

A big part of the missed opportunities for the global distribution systems involves the shopping process. When booking on an airline site, for instance, the consumer is often given images and a better idea of what to expect onboard. While GDSs have caught up by creating new travel agent interfaces with this kind of rich content, it’s still hard to expect airlines to place their faith in a channel that not only increases cost of sale but allows them less continuity in the marketing process.

“GDSs are investing a lot of time, money and development effort to merchandise travel better but the most obvious gap that I see is around flight shopping,” said Jonathan Savitch, senior vice president of business development for Routehappy, which provides rich content to airlines. “It’s still a pretty opaque shopping experience, compared to shopping for hotels, for example. In that case, I get a pretty solid understanding of the amenities, quality and product experience. But for flights you don’t know what you bought until you board—long after the ticket transaction. It’s especially frustrating because everyone has caught on to the pricing game—there’s usually only a few dollars difference among the major carriers—but we’re still at the early efforts of merchandising the products rather than just the price. I think most shoppers would pay something to be more comfortable, eat better, or enjoy Wi-Fi and entertainment.”

Future Disruption

Despite the preeminence of Amadeus, Sabre, and Travelport, there is room for new players in the travel distribution space to emerge.

The big problems for these upstarts, however, include access to travel content that the global distribution systems already have through deals and long-term relationships with airlines and hotel chains.

The areas that travel distribution giants have struggled in, particularly airline merchandising and hotel content, are being disrupted by small companies making smart investments in areas of the travel ecosystem that have undergone change in recent years. Not that the global distribution companies haven’t made major strides in the area.

“What keeps me awake at night is that this is an evolving model all the time, and the need to aggregate new content in a faster and a more simple way, is one of those challenges the industry has,” said Travelport’s Clarke. “As content becomes more and more fragmented, you have to continue to aggregate. We've got a 40 year history of aggregating complex global content. I see that getting more complex as we go forward. Our task is, how do we do that at scale, at speed, to make sure that we provide relevant consumer choice? In the intermediary channel, you have sort of an unbiased, unfettered access tool of that disparate content that's out now. It's not a simple task.

"Content is a minimum. It's the relevance of the content, it's the speed that you provide it at, and it's the full and richness of that content, including these things such as ancillaries and imageries and the ability to consume and buy that content, is actually sort of where it's moved. I may be proved wrong, it's just how I feel.”

From the travel agency and online booking site perspective, however, there is a sense that the global distribution system companies can’t be relied on to create technology solutions that would disrupt their own place as intermediary of choice.

“I predict there will be a tipping point – which I think we are close to – where travel agencies will begin to take more control over their technology decisions and begin to incorporate more aggregation technology, which will become more readily available as more airlines support a direct model,” said Farelogix’s Davidson. “The GDSs want to protect their market position and revenue model at all cost. That is clear based on what has been revealed in the lawsuits and trials.”

The technology behind blockchain could also one day redefine how travel companies market and sell their products.

If you keep hearing the term "blockchain," but still don't really know what it is or does, no shame—this video is for you. pic.twitter.com/t6VMVMapJY

— MIT Tech Review (@techreview) July 24, 2017

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

Winding Tree, one effort to develop a blockchain ledger for travel selling, posits that a decentralized marketplace will be beneficial to almost every industry player, from travel providers to consumers, except for the global distribution system companies.

“A lot of people are asking me whether the online booking sites or GDSs have to go, and the answer is no,” said Maksim Izmaylov, a founder of Winding Tree who previously founded hotel technology company Roomstorm. “They don't have to. What has to go is the rent-seeking business models, the abuse of power that they're exercising and that they are able to exercise today. The path between the ability to exercise monopolistic power, and actually doing that, is very, very short.

“If someone has the power to make millions and billions of dollars, I guess it’s just human nature: people will do it. Maybe it's not a single person in those companies that is responsible for that, but the whole company somehow, just naturally it's going to happen. The GDSs and booking sites, and all those middle men, they don't have to go… [but] If you remove that very easy source of revenue, of course they will innovate.”

Blockchain technology may seem complicated, but its core features are simple. In this case, travel providers and sellers can access the platform with tokens that can be acquired from Winding Tree, which allows them to list inventory and place transactions on the group’s blockchain ledger. They’ll be able to sell products for nearly free, instead of having to pay a GDS for access to their database or to facilitate a transaction like they do today.

Those transactions will be secure, due to the technology of blockchain, which hashes data, and the thousands of computers around the world which would carry a copy of the ledger.

“All those [distribution] problems we can now solve with a few simple rules,” said Izmaylov. “The idea is behind bringing the blockchain technology to the travel industry, and we're solving problems like network inefficiencies. Blockchains, fundamentally, allow us to reduce the cost of networking, and the cost of audit, because we have a completely transparent ledger. At the same time, we'll lower the barrier for entry for new entrants, therefore, [eliminating] one of the problems today in the travel industry: we cannot innovate.”

He gives the example of a fledgling travel booking startup trying to break into the industry which can’t because it needs to negotiate for access to a global distribution system to access content and pricing information. The cost of accessing the system can kill a startup that isn’t well-capitalized. There’s also the matter of industry politics, important for getting access to global distribution system content; too disruptive a concept, and your company may be denied access.

A blockchain-based platform would eliminate this challenge, allowing travel companies to list their products and sell them on a platform offering a lower distribution cost than a traditional GDS, and anyone can buy the tokens needed to participate in the marketplace.

“What we're replacing here is not just the technology,” said Izmaylov. “It's not just to decentralize the marketplace. What we're proposing is a change in the governance model. Today, for example, we have a bunch of different players. We have IATA. We have, of course, Sabre and Amadeus, which were created by a group of airlines. The fundamental problem with those organizations is they can innovate once a year or in the case of IATA, for example, once in five years. It just doesn't make any sense. That's why the industry is 10 years behind, and that's why I'm saying that the whole system has grind to a halt.

“We need to radically change and rethink how we innovate. We need to decrease the feedback time between what customers, travelers, or businesses around the world actually need, and what anyone who can produce good software can deliver. That's what we're changing here, so with Winding Tree the idea is that one part of that platform is the actual marketplace, where suppliers of travel can create their inventory, can sell their inventory to travel agents, which could be a mom and pop shop, or a website, or an iPhone app. Doesn't matter. It's just a set of APIs.”

Winding Tree itself is looking to set up as a Switzerland-based non-profit, and is planning its initial token sale later this year. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission ruled that tokens in the blockchain ecosystem should be treated as securities, which may complicate the group’s effort in the U.S.

This approach, in its current form, faces other challenges. If many travel companies don’t use the platform, it won’t have enough relevant content to be an effective alternative to a global distribution system. There is also a question of governance; since the companies and individuals who use the platform will have a say in how it is run, corporate or political interests could shape its development.

There is also the possibility of the global distribution system companies or another travel company creating a private blockchain. Instead of being able to buy tokens and use the system which is distributed across public networks and governed by a public group, a company could use the technology and only allow access to its internal teams and selected partners. This could theoretically allow these companies to move away from wider global distribution system distribution by offering a lower cost of distribution to select clients, akin to a direct connect.

Webjet has already developed this technology for internal use, according to a report from Coindesk, and other larger players are also working on new systems using this technology.

Next-Gen Distribution

The utility of blockchain in travel distribution has yet to be proven, but there are other startups doing innovative things that could move towards the mainstream.

Some companies ease the process of connecting a travel provider's system to the global distribution system; Farelogix is probably the most successful of this subset. Others, like Routehappy, provide more advanced revenue management and marketing tools to airlines.

New booking sites are also popping up powered by direct connections with airlines, and are poised to provide airlines with the ability to sell and market their products with more flexibility. With the travel industry booming, and the global economy growing, travel providers are now able to experiment with new channels in ways they might not be willing to during a downturn.

Berlin-based Flyiin represents a new way for airlines to sell flights. By connecting with airline APIs, the service will allow consumers to search flights from multiple airlines and add-ons using an intuitive interface. Users can specify up front what types of flights and what kinds of ancillaries they want, and have the full cost rolled up into their search results.

The service is really a messaging platform at heart, instead of a search platform; it crunches airline fare information on the back-end and aggregates messages from airline APIs into easily digestible results for consumers.

"Ten years ago, on behalf of Amadeus, a colleague of mine and I made a tour of 24 airlines around the globe," said Stéphane Pingaud, co-founder of Flyiin and a former Amadeus distribution executive. "The whole point of that tour was to see how the GDS should evolve in the future to better meet the needs of partners. What came out of this is what this product is trying to address, that concept of marketplace. It's just now it was technically possible because of the airline wanting to have a direct interaction with consumer and travel agent, and to market the fares in a way that isn't a commodity.

"They want a lot of data, because the airline gets the search request directly, and can use it to get real-time behavior on whats going on: what kind of product are [flyers] attaching to which destination, for instance. It's totally impossible through the GDS. It's all been very clear to me that the GDS will never be bypassed as a channel, because the value is no longer so much in the tech prowess of their platform but more about their reach and numbers of points of sale."

The site will launch a beta version later this year for users in Europe, but still hasn't sorted out its exact business model. The thinking is that allowing airlines more control over their offerings and bringing them higher-yielding customers, in a marketplace with rich content and without booking fees, will be extremely attractive to airlines, leading them to support the channel.

"It makes sense they pay a price for [GDS] reach," said Pingaud. "What pisses off clients is that if you are paying a price that keeps rising and your channel doesn't actually improve. You're subsidizing a market share game across the GDS. If the GDSs were to do something like us and reinvent the way your airline product is being marketed to travel agents, the airlines will be delighted. The problem is to do this you have to be bold and build a system from scratch."

There are other areas besides flights that have drawn interest from innovative companies. Peakwork, which provides dynamic packaging tools, caches data from travel provider APIs to provide a more refined way for booking sites to construct packages and for consumers to search for attractive package deals. It's also a channel for tour operators to avoid paying large fees to the global distribution systems for distribution.

Peakwork partners with the distribution systems to provide some flight content for its clients, which include major tour operators like TUI, and has partnered with online booking sites to produce more intelligent packages. Packaged travel is one area which the global distribution systems aren't well-equipped to handle due to the nature of their search and booking technology where different trip elements are siloed. They've also launched a trial with Google to provide flight and hotel package metasearch in the UK and Germany.

"The markets are much more fragmented and there are many more players disrupting the GDS space," said Annika Kessel, senior vice president of global business and managing director of Peakwork. "The one key factor is where younger companies will say that GDSs are big legacy systems who made their business model off low look-to-book ratios and that has to change. Search has to be flexible. You can basically send an open search to the API without getting the departure or origin, and I think GDSs with their decades of systems with increasing complexity are not able to deliver the best results."

The need for dynamic packaging also speaks to a broader trend in the global travel market; while the North American traveler isn't used to buying travel packages, other regions around the world have embraced packages, with half of UK trips, for example, being booked as packages. This sort of wider global focus is something that is hasn't been adopted by North American travel companies.

"The U.S. understands packages differently than a European customer or an Asian customer," said Kessel. "European customers are more used to buying packages and living in an environment where packages are constantly advertised. The trend is that the market is only slightly increasing, but in Asia-Pacific with heavy growth of travel demand, that's where packages are at a very pivotal point and there will come a lot of growth. We believe the package market size is around $300 billion and the overall travel market is $1.2 trillion."

There's also the reality that exploring partnerships with companies like Google and Facebook, which already command a huge presence in travel inspiration and search, is the wave of the future, even if Google has held back from a full push into selling travel because of its lucrative business selling advertising to travel companies.

"What we see is that now there is a very large consolidation happening [in travel distribution], like the Kayak-Momondo deal," said Kessel. "When it comes to these big media companies, they can't be seen as an enemy. It's important for [travel companies] to get into the channels that will dominate more and more of the ecosystem. All the media houses are so good as a marketing engine, but they need [travel companies] at the shortest possible value chain by placing the products directly into their marketplace."

An Unclear Future

It’s unclear what exactly the future holds for the global distribution system companies, but new technology certainly will guide the evolution of the travel distribution ecosystem. As New Distribution Capability adoption continues to grow for airlines, smaller players will likely have more of an opportunity to create innovative solutions that may not involve the distribution incumbents.

“Everyone wants to be fast like Amazon but there are lots of reasons even Amazon doesn’t sell flights,” said Routehappy’s Savitch. “I think two things need to happen in parallel. First, GDS tools need to continue to improve. Sabre’s new Red workspace is a good example of better merchandising and those kinds of richer platforms can’t come to market soon enough. Second, incentives need to better align. American Airlines’ recent NDC announcement is a good example and I think it’s one the industry will build on.”

There's also the specter of search and social networking companies, with their direct access to consumers, making a stronger push into selling travel. The idea of playing ball with yet another intermediary, even if they charge a fee for access much lower than that of the distribution systems, is not yet an attractive choice for travel companies when they can continue to push consumers to their direct channels.

"What role are Google, Facebook, and TripAdvisor going to play?" asked Lenza. "Are they less scary than the current players that exist out there? There's been engagement with these guys in many dimensions, trying to get them to be friendly with the industry and support direct initiatives rather than become another intermediary. No one can predict how they will play this, but Google is a huge threat."

Representatives of each of the big three global distribution system companies said their goal moving forward is to work with industry partners to make sure everyone’s goals are aligned, something that has been missing in the last decade as airlines have pursued consumer-direct strategies.

But if Facebook is suddenly willing to open up its user base of more than one billion people around the world to travel companies in a more comprehensive way, expect many to jump on board.

“I think if we're not sober about the amount of competitive activity in the travel space, it would be naïve,” said Sabre’s Jones. “We think a lot about emerging technologies and disrupters to the GDS. People have predicted the demise of the GDS for a very long time. But I will say that what gives me some comfort is that the role that GDS plays in aggregating in the number of hoteliers, travel companies, cruise lines, etc. I think that's going to continue to be an important role for aggregation and technology companies that have the ability to do that and become more flexible which is, obviously, our area of focus.

“We need to apply some retailing principles, some merchandising principles that apply to all kinds of markets, not just the travel market. So how do we help advance the travel market to be able to retail and merchandise products, not be an improvement over the old products in travel, but to be consistent with what customers expect across all types of merchandising and retailing platforms, whether that be Amazon, Alibaba, Airbnb, and others.”

Yet, companies like Airbnb or Uber didn’t exist 10 years ago. The pace of transformational change in travel, enabled by technology, has sped up. Global distribution system companies, however, are well-positioned to remain relevant to the travel marketplace in years to come.

There’s also the prospect of some sort of transformative change, whether using blockchain technology or some other unheralded solution that could remove friction from the marketplace and drive down costs for travel companies. And what about the effect these kinds of solutions could have on consumers and travel agents, empowering them to make more well-informed travel purchases with the ability to make changes to their bookings as they see fit?

Companies around the world are creating innovative solutions to the problems in the global travel distribution marketplace. It's only a matter of time until they hit the mainstream.