Skift Take

We're not saying flying cars won't exist; they already do. But at this point, it's ludicrous to expect the market to grow beyond a niche offering for the wealthy anytime in the next few decades. Don't buy the hype.

Based on frothing media reports, one could legitimately expect travelers to be zooming around the skies like George Jetson in flying cars within in the next five years instead of being stuck in the back of an Uber or Lyft during rush-hour.

The reality, however, is much more complex. Not only is the degree of difficulty in designing a safe and efficient flying car exponentially more extreme than building an aircraft, but regulations on noise, fuel efficiency, and safety all point to serious challenges for companies attempting to bring these vehicles to market in a widespread rollout.

The positives are immediately appealing; faster trips, reduced accidents, and less traffic congestion as fewer travelers and commuters use ground transportation options. These vehicles would also be powered by electric batteries instead of fossil fuel, causing less pollution and leading to more sustainable outcomes than traditional commercial aviation or most automobiles.

Uber announced late last year that it plans to test a fleet of flying cars at the Expo 2020 World Fair event in Dubai, fueling the perception that this field of technology is perhaps more advanced than it appears. Innovative cities around the world, as well, have signaled that they are open to providing these types of solutions to residents.

Dubai has announced it is ready to operate a fleet of single-passenger flying cars developed by Ehang, a Chinese company which is known for producing consumer drone devices. These autonomous aerial vehicles are expected to be introduced in July, according to Dubai’s Road and Transport Authority.

German company e-Volo has also partnered to bring its vehicles to Dubai later in 2017.

“The opportunity is really huge, and Dubai’s aim is to be a pioneer in this field,” said Alex Zosel, co-founder and chief innovation advisor of e-Volo. “They are driven by making these laws and working hard on the regulatory parts for these kinds of aircraft. We believe that a lot of other cities are following Dubai’s lead.”

At the Paris Air Show in June 2017, a variety of companies showed off prototypes of flying cars intended to fly with and without pilots.

There is also the challenge of how this technology intersects with the field of urban and transportation planning. While companies investing in flying cars would like to portray the field as utopian and a step forward in connectivity, the reality is that other simpler forms of transportation may be better-suited to solving the problems faced by cities and commuters.

“I find the territory of driverless cars frustrating because we’re getting slightly more balanced in the debate, but there is an almost myopic view that this is inherently a wonderful thing for society,” said Glenn Lyons, associate dean at the Faculty of Environment and Technology at The University of the West of England, Bristol, and an expert in sustainable urban transportation networks.

“It has moved from it being a pipe dream for decades that we may have autonomous cars, and only in the last two or three years has there been this hype around it. To so quickly, on the back of that, be moving to yet a new hype cycle on new flying personal vehicles, my instinctive reaction is one of being appalled because it raises the questions of what the motivations are for this by the [companies involved].”

Uber Wants to Lead

Let’s start with an examination of a lengthy whitepaper released last year by Uber detailing its ambitions in the space along with the technological and regulatory hurdles faced by flying cars, or vertical take-off and landing vehicles (VTOLs).

Uber has identified this type of vehicle, which doesn’t need a runway to land and takes off like a helicopter, as its target for the mass-produced flying car but other startups have created functioning flying cars that do need a runway or will only work over water.

These vehicles work by using more than a dozen rotors to propel flyers around; the more rotors the better, since redundancy is important for safety. How long they can fly depends on whether the model is designed for short or long flights; the Volocopter model set to debut in Dubai this year is intended for flights of 20 to 30 minutes before recharging, while others may fly longer distances. The less a vehicle weighs, the less thrust is needed to take off, so lighter vehicles hold the most promise.

The idea that flying cars will become mass-market vehicles in the near future is called into question by the report.

“An essential question is whether VTOLs can achieve a sales price point below the current price of commercial helicopters,” states the whitepaper. “If VTOLs are expensive, then the market size will be limited due to poor value for consumers, which feeds back to further limit vehicle production.

“This snowballs into VTOLs being a cottage industry for the wealthy not unlike Lamborghinis. Although helicopters have existed for decades, their commercial appeal has not grown to the point of breaking out of the low production and high vehicle cost cycle. In fact, global non-military rotorcraft production is projected to total just 1,050 in 2016.”

There is a case for looking at the flying car market as a space more similar to helicopters in commercial aviation than regular automobiles.

“We’ve had elites in urban areas that have helicopters,” said Lyons. “Do I think flying cars are going to replace cars? No, but it is feasible to think they have a market share of five percent. Who will use them: privileged high flyers who cause noise and pollution. It’s hard to see a path of development [for flying cars right now], and I think we need to avoid this separation between individual and collective transport.”

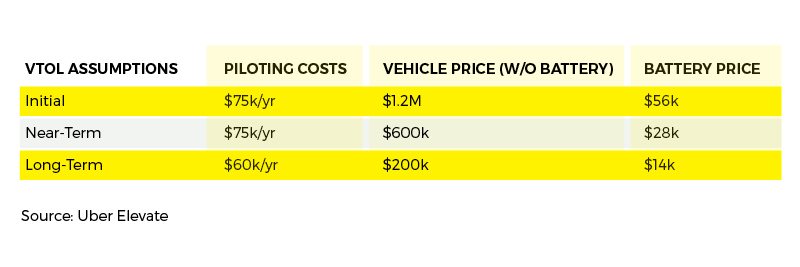

Uber breaks down the potential cost of operating these vehicles:

These costs, understandably, are much higher than that of a traditional automobile.

Without getting too deep into the weeds on the costs of being an Uber driver, buying a fleet of flying cars and operating them would represent an entirely new model for Uber. All things being equal, they’re likely to partner with whichever company wins the battle to create the most reliable, and cheapest, flying car model.

For e-Volo, which is just one of many players in the space, testing the vehicles now will allow them to ramp up production and make them more affordable.

“Not everybody can buy this, it’s really not cheap; it’s more of an early adopter luxury thing,” said Zosel. “It’s just like a taxi; if you produce a lot of these aircraft the price goes down. If you produce 100,000 a year, it can be much cheaper. We think [these vehicles are] for everyday use in urban space and will become affordable.

“We think that [the market is] coming fast and we want to produce 100,000 of these things within 10 years, not 20. Uber, for example, have their vision. Uber’s plan is to earn money with their ecosystem like they earn money with cars but don’t own cars. We don’t know if Uber is the player to control the system in the future. Our plan is more of an urban thing in bigger cities; Uber’s vision is that they see more [of an opportunity] between the cities at longer distance, and the aircraft have to be faster and fly longer distances.”

The ridesharing giant does not own the cars its drivers use, although it does lease cars to drivers in markets around the world where car ownership is limited. Obviously it’s easier to lease and maintain a $30,000 Honda Civic for a driver than a $200,000-plus airship.

“As we described throughout our analysis, we believe the urban air transportation ecosystem will only be successful with the participation of entrepreneurial vehicle manufacturers, city and national officials from across the globe, regulators, users, and communities who will be keen to interact with one another to understand how the ecosystem can shape the future of on-demand urban air transportation,” concludes the Uber report. “While we have explored internally how to fast forward to a future of on-demand urban transportation, we have a considerable amount to learn from a wide, experienced and varied set of stakeholders.”

The report also glosses over an important factor regarding the companies that produce these vehicles: they want to sell more vehicles, not fewer. If the economic case isn’t there for the mass production of drones that carry human passengers or legitimate flying cars, it is possible they move onto other products with bigger potential markets.

“There’s been discussion of VTOL systems which in many ways are simply helicopters, and as Uber describes it in the initial deployments there will be a pilot in the aircraft,” said Bryant Walker Smith, an assistant professor of law at the University of South Carolina and an affiliate scholar at Stanford Law School’s Center for Internet and Society who teaches classes on the legal issues facing autonomous vehicles. “Pilots for passenger aircraft for some of the regional carriers probably don’t make much more than an Uber driver, so the economics in terms of labor might be there for a piloted aircraft.

“The other realm has been the extension of unmanned aerial vehicles into longer development that could at one point produce a version that could carry a non-pilot passenger. That’s a unique technology development from Uber’s VTOL, and then other companies sort of working inside those margins like Airbus that see this as a lucrative emerging field probably in the same way that automated driving was seen as something you need to be involved in lest the tech overtake you and you end up feeling behind.”

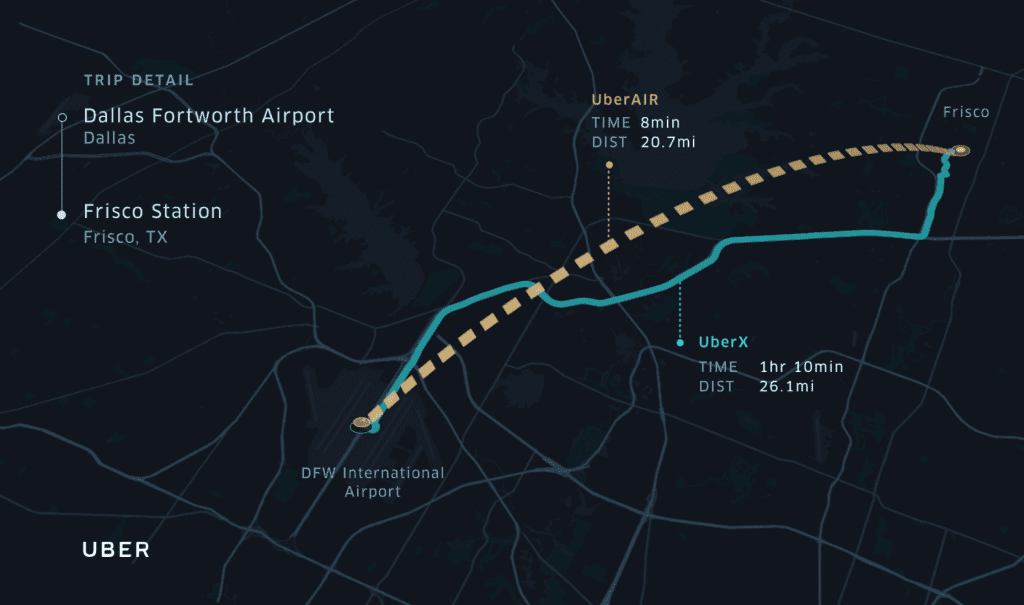

In a presentation at its Elevate conference last year, Uber laid out a vision for how its customers would benefit from the emergence of these vehicles as a complementary product offering to its ground transportation services.

A seventy-minute drive from Frisco, Texas, to Dallas-Fort Worth Airport becomes an eight-minute flight using Uber’s flying car fleet, excluding the time it takes in an Uber X to drive to Uber’s skyport facility to board the flying car.

All the regulations which will need to be developed by the Federal Aviation Administration and other groups are still being negotiated. Price also hasn’t been detailed but executives insist such a product would be priced competitively with Uber’s other offerings.

You can watch Uber chief product officer Jeff Holden’s full presentation on Uber’s flying car ambitions here.

Regulations

The regulatory road to mainstream use of flying cars is more straightforward than you might think.

The FAA only recently required drone owners to register their devices, so it is fair to expect it to take years to develop a comprehensive set of regulations regarding flying cars. But the FAA regularly grants waivers to companies that develop drones and other airborne technology.

In fact, the FAA has already granted waivers to companies developing flying cars. In 2010, developer Terrafugia was granted a waiver to remove weight restrictions for the test of Transition, an early model of a flying car that requires runways. Consumers can currently place a $10,000 deposit to reserve a model of the two-seat aircraft that can also drive legally on roads.

Terrafugia also received a waiver last year for a newer version of its Transition vehicle.

Compared to the arcane and complex regulations governing automobiles through the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), the FAA represents a far more attractive route for developers.

“Pilots are really important to the flight and they are wholly under the domain of FAA, along with aircraft and airspace; they’re a one-stop shop for a developer of these systems,” said Smith. “The FAA has a broad ability to provide exemptions, while NHTSA is different. If a car manufacturer can’t or doesn’t want to comply, that manufacturer has to seek a specific limited exemption that’s not economically attractive. The FAA can give much broader and effective waivers from its requirements and has a much more established process for figuring it out.”

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration is already developing an air-traffic control framework for drones, which could track unmanned flying cars that fly under 500 feet high in the air. The system is planned to be automated, providing data on aircraft during flight that can be used to prevent collisions and efficiently manage airspace.

There are also, of course, the internal hurdles a prototype must pass before being considered for wider public testing.

You can see partnerships between established vehicle manufacturers and global aviation startups as a sign of this; it may be better for companies outside of aviation to partner with others to help bring this technology to market. Startups can focus on crafting vehicles designed to cope with specific problems, like longer or more fuel-efficient flights, but may lack the muscle to mass-produce them and partner with governments on regulatory issues.

Toyota, for instance, has provided funding to Japan-based startup Cartivator, which is developing a drone-like vehicle that would fly 30 feet above the ground.

Aviation giant Airbus Group is developing multiple models of flying cars, including Project Vahana, which is applying lessons from the company’s helicopter division to urban mobility. It is also experimenting with skyports to accommodate flying cars, on-demand hailing, and unmanned aerial vehicles.

[vimeo 221950605 w=640 h=360]

There are many other companies working to create flying cars across the world. The competition is real for investor dollars and partnerships with the giants of travel and transportation. A look at the self-driving car marketplace overall can be instructive when examining the prospects of flying cars.

“It will be a necessary gateway when these technologies have matured to the point they have been deployed, but I think there is a perception that big companies are coming up with half-baked systems and going to a regulator and saying figure out if this is safe,” said Smith. “What that misses is the fact these mature established developers are not going to seek regulatory approval of a system that they’re not supremely confident in.

“The internal processes for the developers are very lengthy from the initiation of the idea to the prototyping to the development of the system. Even before that, they have concrete discussions where managers and engineers are going to be asking how do we know this is safe? What are our internal best practices? Waymo [Google’s self-driving car company] has now been testing its automated driving systems for years publicly and it’s not that a state hasn’t passed a law or they need or that certification that kept them from mass deploying.”

Consumer Perspective

There is also the greater matter of consumer behavior. Uber claims its goal with self-driving car technology, for instance, is to enable consumers to earn money by deploying their vehicles when they’re not using them, which is up to 98 percent of the time according to research. But as transportation becomes further commoditized, rapidly becoming a service for purchase, will a reduced need for travel due to innovations in communications technology ultimately subvert these trends?

“Mobility is a consumption behavior,” said Lyons. “Unless we’re looking at these tech companies as almost pseudo-philanthropists for society, they’re ultimately out to make money and you’re going to make less money selling cycle trips than flying cars. It’s a fundamental difficulty for us. We want economic prosperity and sufficient mobility; we don’t want limitless gratuitous mobility. I can’t see it being in the interest of the motor manufacturers to have less vehicles being used more efficiently unless that somehow increases demand so that after-sales create profits for them.”

Consumers are concerned about the safety of these vehicles. In a survey conducted by academic researchers Michael Sivak and Brandon Schoettle at the University of Michigan’s Sustainable Worldwide Transportation department, 62.8 percent of 508 U.S. adults polled said they are very concerned about the overall safety of flying cars.

Some 40.9 percent said they were very interested in owning a flying car, and 16.7 percent felt very positive about flying cars in general. Overall, automated flying cars would be preferred over pilot-operated models, which is surprising considering autonomous cars have yet to be deployed en masse.

“About two-thirds of respondents were familiar with the concept of flying cars prior to participating in this survey,” the report states. “For taxi-like versions, fully autonomous flying cars (self-driving and self-flying) were preferred over those operated by a professional with an appropriate pilot license… For personally owned versions, fully autonomous flying cars (self-driving and self-flying) were also preferred over those operated after obtaining an appropriate pilot license.”

A survey of 1,009 U.S. adults by Allianz Global Assistance and IPSOS found that 51 percent of those polled are not confident that flying cars will be safe when they finally enter service, and 48 percent aren’t interested in flying cars as a future mode of transportation at all.

It seems that consumers today are interested but uncertain about flying cars. But the consumer of the future, who is now a child, may have different thoughts about how flying cars could fit into their lifestyles as they enter the workforce.

The bigger question could be how society at large views a potential shift to aerial transportation in the mainstream at a time when some public transportation systems across the U.S. and elsewhere are struggling to cope with increased ridership.

“If we allow the tech companies to run away with themselves and create cities overrun with flying cars and autonomous drones, is that the only way of achieving a better future?” asked Lyons. “Wouldn’t it be wonderful to make cars more efficient and take them into a third dimension and solve congestion?

“What history has told us is that we’re not very good at locking in the benefits. When we provide more capacity, or make it more efficient, it induces more demand and encourages more use of that system. If we can use it more, we get more connectivity and interaction in society. But there is the real danger that we haven’t developed solutions which are as long-lasting as we had hoped. There is a strong connotation of toys for the boys here.”

Futureshock

The race to develop a flying car that is also a mass-market vehicle is only just beginning. Autonomous cars also face a long road to entering the mainstream.

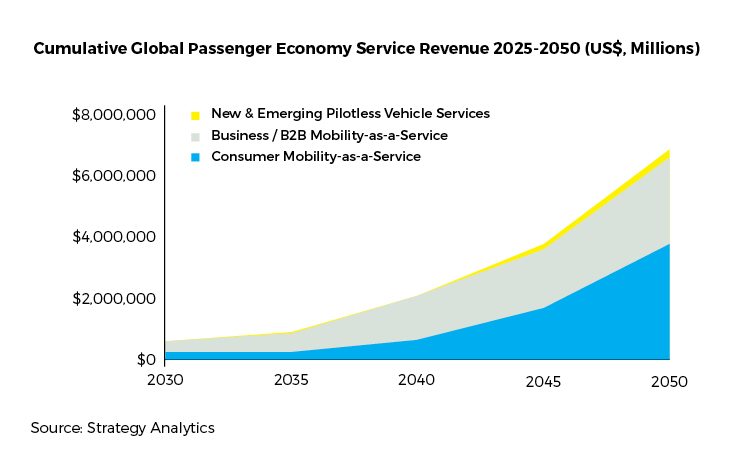

A recent Strategy Analytics report, Accelerating the Future: The Economic Impact of the Emerging Passenger Economy, shows the long runway that exists for both automated vehicles and flyings cars.

Pilotless vehicle revenue is expected to lag far behind both consumer and business mobility-as-a-service (transportation services provided by companies like Uber) even in the year 2050.

(The graph’s Y axis represents cumulative revenue among three sectors of the industry, showing that pilotless vehicles lag far behind more traditional transportation services.)

The group also doesn’t expect driverless cars to be manufactured in any significant capacity until the 2030s. Shifts in consumer desires and behaviors could be significant by then when compared to today.

“By the time driverless cars are envisioned to be delivered, let’s not assume the rest of society has stood still over those years,” said Lyons. “Right now, any envisioning of the future is with Google and smartphones standing still. I look forward and ask myself how will social practice change in the next 20 years. Will younger generations be less likely to be tied down to who they work for, where they live. Will they be using digital connectivity to enable this social [change]? Perhaps they’ll reach a point where they don’t need the rather dated idea [of commuting to an office each morning], although I’m not suggesting we won’t have a need for conventional transportation.”

There is also the bigger issue of Uber’s attempt to take ownership of the sector. As the company has moved to define itself as a platform for mobility-as-a-service, selling various types of travel and logistic services to consumers and businesses, it also has to eventually figure out a way to make money.

Waymo’s lawsuit against Uber, in which it has accused Uber of stealing its proprietary self-driving car technology, is a sign of the importance of this sector to the transportation giant as Uber seemingly inevitably prepares to go public.

With product rollouts being determined more by what is profitable for transportation networking companies than customers, will many end up being priced out from potentially game-changing technology advances like flying cars? How will manufacturers and travel brands be able to differentiate their products and market to consumers in such an environment?

“I wonder how socioeconomic inequality figures into these technologies and the public context,” said Smith. “Uber in particular has made the argument that this will be affordable for people who can afford Uber Black if not Uber X. That would be an interesting world if these were accessible. What always concerns me is that we’re seeing these technologies more likely initially deployed as luxury goods, and there’s clearly an increasing market for luxury goods that separate the wealthy from the rest of us.

“I don’t know how that figures into public policy or figures into the public perception of these products. It’s not like a new AI-based algorithm that affects pricing decisions on an airline website; we don’t see that face-to-face, we see self driving cars, unmanned aircraft systems, and single passenger or limited passenger shuttles. How will people feel about that if they feel threatened by technology in other ways. How will they feel about little [luxury] shuttles zipping over their head?”

Whatever happens in the U.S., the future is being written right now in the skies of Dubai. And it won’t be long until the flying car, once an emblem of the greater goals of mankind, becomes an option for travelers around the world.

The average consumer, however, may still have to wait.

The Daily Newsletter

Our daily coverage of the global travel industry. Written by editors and analysts from across Skift’s brands.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: flying cars, local transit, ridesharing, uber

Photo credit: Flying cars are a hot topic for the media, but potentially years away from becoming a mainstream transportation option. Visitors look at the flying car Pegasus 1, built by French entrepreneur Jerome Dauffy, at Paris Air Show. Michel Euler / Associated Press