Skift Take

Museums can be powerful drivers of tourism and the newest Smithsonian, which quickly became a black American mecca, sets the bar high. Case in point -- how many museums have a line to get into the gift shop?

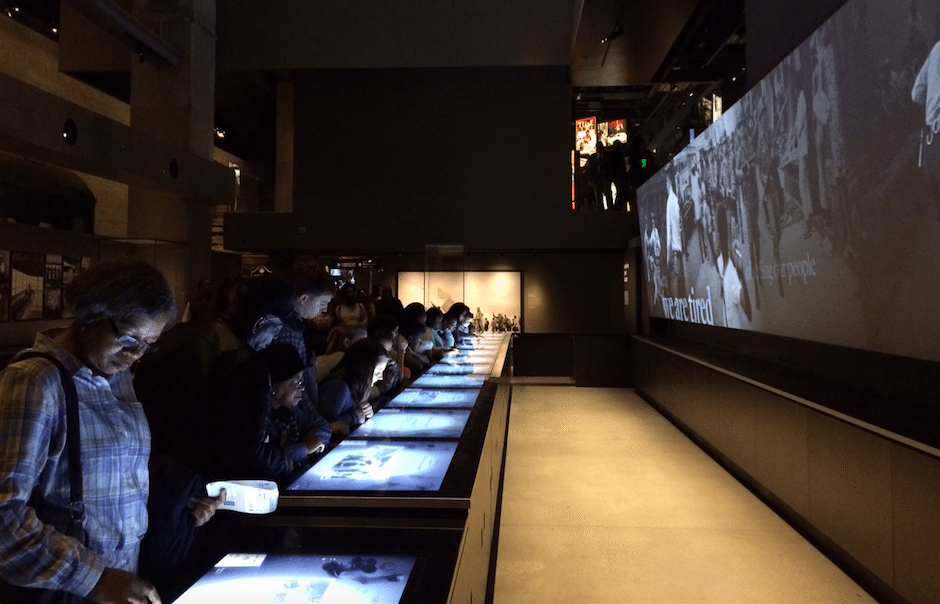

Today’s successful museum isn’t a stuffy old gallery fit for groups of bored schoolchildren — it’s a world-class attraction that visitors clamor to share on Instagram. A modern museum is expected to offer an acclaimed restaurant, a design-centric boutique with a lot more than branded pencils, and an immersive, photogenic experience in the galleries.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. sets the bar high. (The acronym NMAAHC is both clunky and unpronounceable, and doesn’t do the museum, which is the newest under the Smithsonian umbrella, any branding favors, so it’s referred to here as “the African American museum.”)

The museum opened to great fanfare in September 2016 at the end of America’s first black presidency under Barack Obama, after 13 years of planning with $540 million in funding. The building’s bronze architecture recalls a Yoruba crown; the theater bears Oprah Winfrey’s name; the grand opening saw Stevie Wonder, Patti LaBelle, and Common; and crowds from around the country and world quickly spread about the new black America mecca.

A Powerful Tourist Attraction

The African American museum is well-positioned as an attraction, as well as a valuable piece of cultural heritage. The museum released a special app for the grand opening that included a trip-planner, which helped visitors find hotels and restaurants, and navigate the city by car, ride-share, or public transit. Hopefully the museum will incorporate these features into its regular app.

In a conversation with Ta-Nehisi Coates at The Atlantic’s Washington Ideas Forum last fall, the museum’s director, Lonnie Bunch, said that the strength of the Smithsonian brand raised public interest and vice versa. “The Smithsonian moved because the public got excited,” said Bunch, who previously worked with two other high-profile Smithsonians: the National Air and Space Museum and the National Museum of American History.

The African American museum’s central location on the National Mall couldn’t be more tourist-friendly, an easy five-to-10-minute cab ride from Union Station, and the fact that it’s America’s only national museum devoted to black history means that it has little competition. It can coexist with other big-name museums on the National Mall that have different audiences and focal points, the way that New York’s Museum of Modern Art coexists with the more traditional Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The crush of visitors to the African American museum — breaking one million as of mid-February — required the museum to adopt timed tickets, which quickly booked up months in advance. A limited number of day-of reservations are snatched up daily at 6:30 a.m.

Tickets for June just became available on March 1 at 9 a.m. On that day the museum temporarily dedicated 75 percent of its Web capacity to the release; eTix increased its number of call center reps and 110,000 tickets were issued to the public before noon. Tickets for July become available on April 5.

Tickets are free, as with all Smithsonians in D.C., but although tickets don’t generate revenue directly, the crowds not only spend money in the shop and café, but raise the museum’s profile for hosting events and other revenue-generating activities.

The American Alliance of Museums reports that museums “directly contribute $21 billion to the U.S. economy each year and billions more through indirect spending by their visitors.” In addition, “There are approximately 850 million visits each year to American museums, more than the attendance for all major league sporting events and theme parks combined (483 million in 2011).”

According to a 2011 study conducted by Mandala Research on African American travelers, 30 percent reported visiting a museum that covered African American history, art, or culture while traveling, and 37 percent reported spending more money than anticipated on cultural and/or heritage activities while traveling.

At the African American museum’s grand opening in September, then-president Obama described the museum as one to visit repeatedly, an important part of D.C.’s tourism landscape. “Years from now, like all of you, Michelle and I will be able to come here to this museum and not just bring our kids, but hopefully our grandkids… and in the years that follow they’ll be able to do the same. Then we’ll go to the Lincoln Memorial, and we’ll take a view atop the Washington Monument.”

President Trump visited the museum in February, then said in a press conference that the museum “was done with love, and lots of money, right Lonnie?” turning to the museum’s director.

Nomadness Travel Tribe, a leader in the black travel movement with more than 15,000 members across three dozen countries, conducted a poll of its members on Facebook last week about the African American museum. Thirty-two percent of respondents already visited it despite the scarcity of tickets; 29 percent indicated they already visited and would also return; and 68 percent responded they haven’t visited but would plan a trip to Washington, D.C. with this museum as the focal point. Some respondents recommended three or more visits to fully experience it, and more than one respondent donated and became a Charter Member, which comes with priority access.

The museum reports that its “dwell time,” the length of time a visitor stays, averages six or more hours on weekends, which is remarkably long. Two hours has long been considered the usual maximum among arts administrators, but at the African American museum, visitors are clearly meant to stay all day.

User Experience

On a recent visit to what’s affectionately called the “Blacksonian,” I arrived at noon on a Friday to see tour buses unloading out front. In the spacious, light-dappled lobby, I approached the front desk. A staffer pointed me to the down escalator to begin my tour of the museum, which is designed to be experienced chronologically from the lowest floor on up. The staffer said that earlier at 11 a.m., “There was an hour wait to go downstairs. You’re lucky.” He said that crowd-wise, Mondays were the lightest days, and the fact that I arrived at lunch-time on a Friday, worked in my favor.

For more details on my visit, click here.

I waited in line for five minutes to descend to the lower-most level, where the narrative begins with the transatlantic slave trade. That’s much like Detroit’s renowned Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History, whose slave ship recreation is immersive and a bit frightening. Docents at D.C.’s African American museum were organized with microphone headsets, relaying instructions to the crowd: no flash photography, no photography whatsoever in the Emmett Till memorial.

The lower-most level was cramped, echoing the claustrophobia of the nearly-pitch-black room evoking the inside of a slave ship, featuring rusted shackles and pieces of wood and iron from actual vessels. The crowd, young and old, hushed and walked slowly through as a deep voice narrated the story. Bottlenecks were most prevalent in this lowermost level, but the layout allowed somewhat for taking different paths at one’s own pace.

The space opened up upon moving into the slavery era. Quotes from black leaders shined in gold high up on the wall and giant videos captured visitors’ attention. Gems such as Harriet Tubman’s shawl and Nat Turner’s bible prompted quiet discussion. One woman asked of another, “How could he read that tiny print?”

Later, in the Ku Klux Klan exhibit, a man spoke to a group of teenagers about dating a woman whose father owned a Klan robe. “He wanted to kill me,” the man recounted.

Visitors engaged with the content; parents spoke to children about their families, some wiping away tears, some unable to move forward from certain items.

On the second floor, while in line for the Emmett Till memorial, a young girl said to her mother about the density of information, “I can only get through so much.”

By this point I’d been in the museum for two hours and started feeling some fatigue; behind me an older couple from Philadelphia had been there four and a half hours.

After waiting in line for 15 minutes, I discovered that the Till memorial was quiet, reverent, and emotional. Till’s coffin was the centerpiece alongside photos and videos describing his disappearance and lynching. Docents encouraged people to move through faster to prevent a worse bottleneck. This floor featured additional interactive experiences, including a replica lunch counter to teach about sit-ins and a segregated rail car, the latter under construction.

I appreciated the well-balanced content, not leaning solely on celebrities like Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, and the tone was truthful. For example, the museum curators portrayed the Great Migration broadly from 1910 to 1970 and noted that black people escaping the Jim Crow South did not find the North to be a problem-free paradise. This insightful approach worked well for Louisiana’s Whitney Plantation, a museum now known for approaching the topic of slavery with brutal honesty, unlike most plantation tours in the Deep South.

The third floor of the African American museum opened up even more, light-wise and space-wise, featuring a Tuskegee aircraft hung from the high ceiling and the most uplifting material yet. A man photographed a young boy in front of a Black Power display and encouraged him to make a fist, smiling and saying “Come on, strong black brotha!”

After the final display, on the Obamas, visitors can duck into the stunning Contemplative Court featuring a cylindrical, light-filled waterfall in the center. The echoing gush of water was peaceful, surrounded by quotes including one from King: “We are determined… to work and fight until justice runs down like water and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

This room also serves a practical purpose: After several draining hours in the core of the museum (the lower three floors), this is a moment to physically recuperate. Recharging makes experiencing the rest of the museum — the café, the shop, and the upper three floors of galleries — possible.

After the waterfall, the Sweet Home Café is a logical next stop. It recently became a semifinalist for the 2017 James Beard Foundation Awards in the category of Best New Restaurant. This seems fitting in the current age of sophisticated soul food, when Harlem in New York is experiencing a tourism surge with hot restaurants like Marcus Samuelsson’s Red Rooster. Sweet Home Café’s executive chef, Jerome Grant, previously worked at the National Museum of the American Indian’s café, which won the 2012 RAMMY for Best Casual Restaurant.

Sweet Home Café experiences a lunch rush, but at an off-peak time like 3 p.m., I waited in line less than five minutes. The café takes regional cuisine (and storytelling through food) seriously, focusing on black traditions in: the Northern States, the Agricultural South, the Creole Coast, and the West Range. At $13, the pan-fried catfish po’ boy with red pepper remoulade and cole slaw on the side was crisp, fresh, and excellent, and seating was full (capacity is 400), hence the brief line to get in.

Seating is family-style at long tables, conducive to conversation about what everyone just experienced in the galleries. The tables are also reminiscent of lunch counters and the associated sit-ins. I spoke to a couple in their 50s for nearly an hour about how emotionally charged the exhibits were, and how relevant it is to their personal family histories of migration from South to North, and then later from North back to South.

Though no line topped 15 minutes on my visit, it’s notable that even the gift shop had a line. I waited less than five minutes but I know someone who waited an hour on her visit. The shop isn’t nearly large enough to accommodate the number of visitors, but it’s beautiful with glass walls and light filtering through the building’s intricate facade.

The shop had a decent array of meaningful books like W. E. B. Du Bois’ The Souls of Black Folk and a small $10 souvenir book on the museum; collectible housewares like mugs, glasses, and reusable water bottles; curated jewelry and folk art; and small affordable tokens like keychains. The Web store, on the other hand, offers far fewer items and recalls the dowdy gift shops of old legacy museums like New York’s Met, i.e. focused on expensive jewelry and basic apparel.

The upper three floors of the museum include additional exhibits and interactive experiences for kids, like sitting behind the wheel of a vintage car while using the Green Book to plan a road trip during Jim Crow. There’s also a forthcoming genealogy center.

I spent five hours in the museum, but easily could have stayed longer, as the museum is truly a multifaceted experience that can dominate one’s trip to D.C. A group of women gathered outside the gift shop and concluded their visit at 5 p.m., and one woman summed it all up. “That was so emotional, my God… I’m hungry. Let’s go eat.”

Room for Improvement

The café sees such high demand, and rightfully so, a small outpost elsewhere inside the museum could help thin the crowd. This way, visitors pressed for time could still grab a drink and a sandwich to refuel without leaving the building. The museum already did this with the jam-packed gift shop by placing a few items for sale on an upper floor. On the downside, a small café outpost might fail to deliver an important experience: sitting down and enjoying the food at one’s leisure and keeping the conversation going.

Since Skift pays increasing attention to the world of food and beverage, I couldn’t help but notice the potential for craft cocktails. If Sweet Home Café tells stories memorably and deliciously through food, why not through drink, not just in the café but in a separate bar with its own regional backstories?

Since people are traveling to D.C. specifically for the museum, adding more lockers would accommodate more out-of-towners. As popularity continues, more people will come bearing bags and other travel accessories they don’t want to drag through the galleries.

Effects on Peer Institutions

San Francisco’s Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD) is a Smithsonian affiliate, which means that MoAD has access to the Smithsonian’s 136 million artifact collection. MoAD deputy director Michael Warr thinks the new Smithsonian’s buzz will increase visibility for many related institutions. “When it’s getting this much love from the public, that type of audience participation from around the country and from around the world… being a professional in the museum world, we’re talking about that,” said Warr.

“I know how transformative it can be when you see yourself in history, and in institutions, particularly for young people, because that’s what happened to me when I was growing up… That’s what art and culture can do — put you in awe,” said Warr.

Along the same lines as the new Smithsonian’s storytelling through food, MoAD has a chef-in-residence program, which according to Warr is one of its most successful, most emulated initiatives. For the future, MoAD is also planning group tours to Washington, D.C. to visit the new Smithsonian.

The Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History in Detroit has a significant collection and delivers an experience similar to that of the new Smithsonian. The experience at the Wright is both immersive and emotional, the collection is highly regarded, and it’s among the largest African American museums in the country. When asked about how the new Smithsonian affects its peers, the Wright’s president and CEO Juanita Moore said, “It brings a lot of awareness, nationally and internationally, to the fact that these institutions exist… It gives people great pride in our institution, the fact that we have one too… it’s been really really nice.”

The two museums have already collaborated — the Wright temporarily took two exhibitions from the new Smithsonian even before it opened. Moore says the new Smithsonian has been “very proactive” in working with other museums, as well as understanding “how the brand of the Smithsonian can benefit other African American museums nationally.”

Moore explained that museums should seriously consider offering immersive, emotional experiences. “If you want to make your point and get people to pay attention… I think you have no choice but to be immersive… We compete with storytelling in so many ways, in movies, at theme parks.”

Museums As Destinations

When New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) completed its massive $425 million renovation in 2004, it reopened and raised the regular ticket price to $20 — shocking at the time. People weren’t accustomed to paying that much for an educational experience, but the sleek new museum delivers much more: upscale cafés that are part of Danny Meyer’s Union Square Hospitality Group, a design-centric store that’s heavily marketed with multiple locations, blockbuster exhibits that go viral like 2013’s Rain Room, and the kind of buzz most institutions would kill for. It draws international crowds year-round. MoMA now charges $25 for regular admission, and while it maintained its free Friday evenings, the full-price days are frequently just as jam-packed as the free nights.

San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art reopened in 2016 after a $305 million expansion. It offers dining by three-Michelin-star chef Corey Lee, an extensive design store, an eye-catching new facade that echoes San Francisco Bay, and a new user experience. The entry fee is $25, and with the new design it feels competitive with New York’s MoMA. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art, another major west coast player, is planning a $600 million redesign, for which it will break ground in 2018, aiming to reopen in 2023.

The Guggenheim in Bilbao, Spain is still a go-to example of a successful blockbuster museum. When the museum opened in 1997, the building designed by “starchitect” Frank Gehry to mimic the Nervión River alongside it, visitation spiked and put the industrial port city on the tourist map. Every mid-sized city in the world wanted its own Gehry to magically revive the local economy by replicating the “Bilbao effect.”

Washington D.C.’s National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) is a premier Native American cultural destination, though on a smaller scale than the African American museum. NMAI opened in 2004 with $200 million in funding. (Bunch noted in his conversation with Ta-Nehisi Coates that the creation of NMAI was not as contentious as the creation of the African American museum.) NMAI’s curvaceous exterior made it a standout piece of architecture, and Mitsitam Café is run by award-winning Navajo chef Freddie Bitsoie. The New York Times ran glowing reviews on both Mitsitam Café and Sweet Home Café — a rare event for museum eateries.

Chicago’s Millennium Park, a sculpture park unveiled in 2004, again involving Frank Gehry, is not a museum per se. However, it found incredible tourism branding success in the sculpture called Cloud Gate, aka “The Bean.” Seemingly no visitor to Chicago can resist putting a selfie on Instagram featuring that giant reflective piece of art. It’s now synonymous with the city itself, an unofficial logo.

Plans are in motion to create a National Women’s History Museum (NWHM) in Washington D.C., possibly on the National Mall, which has the potential for a successful launch like the African American museum. NWHM has been in the works since 1996.

The Daily Newsletter

Our daily coverage of the global travel industry. Written by editors and analysts from across Skift’s brands.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: food tourism, museums, smithsonian, tourism, washington dc

Photo credit: The newest Smithsonian offers visitors an immersive, all-day, multifaceted experience on African American history. Skift