Skift Take

One would hope that a company that has the ears of both the youngest and the most affluent travelers would take its responsibilities seriously: Not only by the way they handle the legal side of the issue, but also in how they lead the conversation in addressing the questions that these laws raise.

Apartment rental site Airbnb’s revolutionary simplicity has made it easy for tens of thousands of people to both list and discover lodging options in private residences and book them easily, quickly, and safely. But a basic search on Airbnb.com for New York City lodging demonstrates that more than half of the available bookings on the popular vacation rental website are likely illegal according to New York State law. Hosts of these units are subject to fines ranging from $1,000 for a first offense to $20,000 for repeated violations, according to a New York City Council bill passed in October.

Airbnb is aware of the problem. It lobbied and spoke out publicly against the passage of the New York State law in June of 2010 that banned a particular yet very popular type of short-term rental in New York City, but it did not make changes to its site when the law went into effect in May 2011. State officials say that Airbnb’s public promises to work with the city on a solution to its illegal short-term rental problem does not extend beyond a heavy lobbying effort to change this law.

David Hantman joined Airbnb as its Global Head of Public Policy in October. He told Skift in an interview that making Airbnb work in New York City is a priority. “We can’t possibly keep up with the law in all the cities,” Hantman says. “Is there a model city? What we’d like to do is figure out a way to make New York the model city. We think we are creating a system that’s better than the current situation. My main goal is to get laws that clear the way for our hosts.”

Airbnb’s promise

Alongside TripAdvisor and smartphones, few companies or products have had as great an influence on how people travel over the last decade as has Airbnb. With smart technology and equally smart design sensibilities, it took the existing concept of vacation rentals, made everything more efficient and reliable, created new markets in urban areas, and got a new generation of consumers hooked on the concept.

“We take something that’s already happening and we make it safer and better,” says Hantman. “We have a rating system so that you get better users, and most of the people renting out their place are responsible neighbors who are invested in getting quality renters.”

It has spawned knock-offs around the world and prompted big-wigs like HomeAway.com and VRBO to rethink their products. Since it was founded in August of 2008 it’s facilitated over ten million nights’ worth of bookings. And it’s just plain fun to use.

Airbnb has signaled that it’s in it for the long haul and it’s got big money to keep it going. In November it signed a ten-year lease on an office in San Francisco. In late October, PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel’s investment of roughly $150 million valued Airbnb at $2.5 billion. This year it’s opened offices in London, Paris, Sao Paulo, Moscow, and other cities in Europe and Asia.

But like the rest of the vacation rental industry, Airbnb has big challenges ahead. It allows listings that are illegal in many of the company’s largest markets including San Francisco, Hawaii, and Paris.

It also faces challenges from local municipalities eager for tax revenue, either in the form of income tax from the owners who use the site or from Airbnb based on arguments that it acts more like a hotel offering inventory than a classified advertising site. (Users are responsible for reporting income to the IRS on their own, but a recent crackdown on owners from rival VRBO in South Carolina demonstrated that sometimes they need cajoling.)

Both of these challenges represent big hurdles along the way to an IPO. The former could wipe out a significant amount of Airbnb’s inventory as well as certain types of users — namely anyone who wants to stay in New York City for less than 30 days in a space they do not share with a local. The latter could force them to pay back taxes on transactions, as Expedia, Priceline, and other online travel agencies have had to do in some municipalities.

Unlike old-school vacation rental websites that merely serve as online bulletin boards connecting owners and renters, Airbnb collects a fee on each transaction rather than charging a user to advertise a unit. This puts it in a position of knowing which units have been rented, for how long, and for how much.

Airbnb doesn’t see itself as a traditional vacation rental website. “We talk about it as a platform,” Hantman says. “We’ve created an ability like eBay that enables people to get together and make transactions. It’s about the hosts and the guests more than it is about us.”

New York, New York

In New York City, one of Airbnb’s largest markets, roughly half of the apartments listed on the site are illegal according to state law. Airbnb has made money off the illegal listings since May 1, 2011 when a law passed by the New York State legislature the previous summer banned short-term rentals in the city. After the law went into effect, Airbnb did nothing to disable listings that break the law nor warn consumers that they were breaking the law.

Prior to May 1, 2011, enforcement often proved difficult because the law did not define a threshold for permanent or transient occupancy, with time periods ranging from 30 to 90 days. Residents had been complaining to local leaders for year about illegal units and conversions, so the city worked with State Senators and Assemblymen to streamline the law to make both compliance and enforcement simple.

The new law defined transient occupancy as less than 30 days and stated that the dwelling’s owner must be present for any rental shorter than 30 days. Additionally, the law strengthened enforcement by defining the use of any single unit of a residential building for transient guests as illegal, not just multiple units within the same building.

This made the difference between a legal and an illegal apartment rental in New York City very clear: If a listing offers an entire apartment in a Class A dwelling — which represent all but a few dwellings in the city — for less than 30 days and the host is not present during the rental, it’s illegal. If the listing is for a room or a space in a dwelling and the host will be present, it’s legal. Also legal under the law are traditional B&Bs, couch surfing, and home swaps as long as money doesn’t change hands.

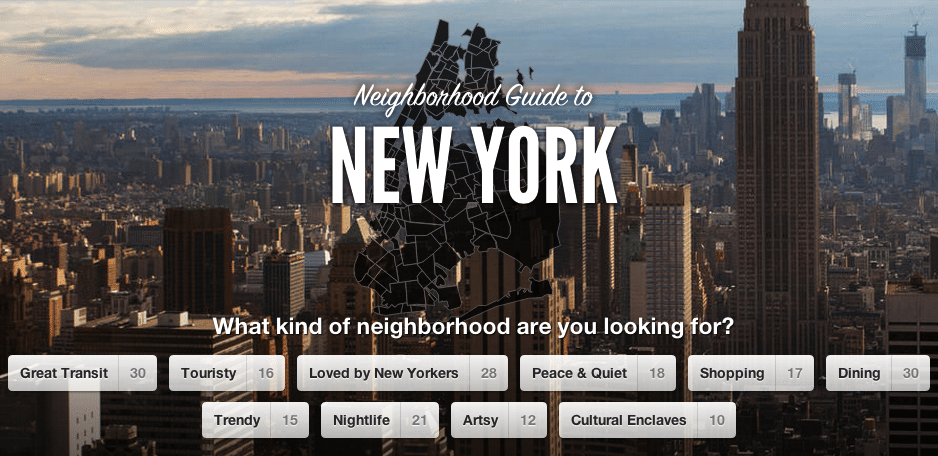

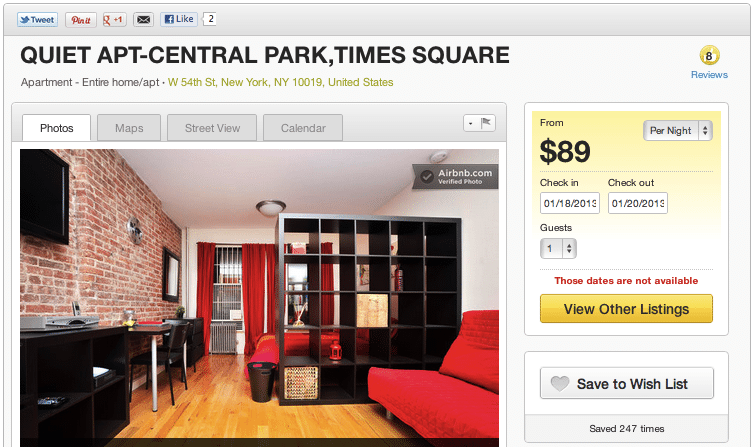

The simplicity of this is easy to see using Airbnb’s search tool. Searching for a two-night rental over the weekend of January 18 in New York City you get a total of 6,176 options if you don’t specify room type, price, or any other options. If you click “Entire home/apt” there are 3,200 results, all of which are illegal under New York law.

New York City investigates illegal hotels and apartment rentals under the Office of Special Enforcement. “We get complaints everyday about illegal hotels,” New York City officials told Skift. “We look at all of them on a case by case basis.” Enforcement activity picked up quickly in 2011 as the city issued 1,897 violations to landlords as a result of inspections for illegally converted residential buildings into hotels – an increase of 244 percent over the previous year.

The Office of Special Enforcement also vacated 51 additional locations – a rise of 75.9 percent from 2010 – for posing immediately hazardous conditions, including lacking fire alarms, adequate sprinkler systems and creating firetraps, for both residents and to the general well-being of the community.

Airbnb doesn’t think the law is clear enough. “It’s a matter of opinion,” Hantman says. “Even for full apartment listings under 29 days some are legal.”

The good

When Airbnb talks about its benefits and its robust community, they’re thinking of examples like Seth Porges. Porges owns a duplex condominium in the Williamsburg neighborhood of Brooklyn. He has a second bedroom that he rents out on Airbnb. “I have tenants virtually every single night. Most stay about a week,” he told Skift. “I’m booked probably 28 days of the month, on average.” And he reports the income on his taxes.

The 91 reviews of his listing are almost all glowing. User Ambika writes “I can’t say enough about Seth and Wray. The house is lovely, the room is awesome and they’re two of the coolest, most friendly, fun, kind and helpful hosts you could ever find.”

“Airbnb has proved absolutely life-changing,” says Porges “It allowed me to fund my startup—the fashion app Cloth and provided me with enough economic security to weather being laid off from my last job until I had things figured out. It’s been the best, most rewarding, and easiest way to make money that I’ve ever encountered.”

The bad

Many of Airbnb’s New York listings are by hosts like Jordan. Jordan offers one listing in the East Village and another on the Lower East Side. Airbnb users are enthusiastic about the properties. User Sherree says “Comfortable and felt like home from the minute we walked in. Jordan really friendly and helpful.”

The properties run afoul of the law, though. Because Jordan isn’t living at the apartments — one listing reads, “However, being that I do not live that close to the apartment …” — and they are available for stays of 29 days or less, they are illegal.

Airbnb’s listings are filled with similar landlords who have two or three units they rent out. Enndy has studios for rent on 54th, 56th, and 57th streets on Manhattan’s west side. The reviews are glowing but the units are illegal and the people who rent them face fines starting at $1,000.

Although the city is using its limited resources to go after bigger fish, they often snag these small players, too. Earlier this month The New York Times‘s Ron Lieber reported on the $40,000 fine one man faced for five violations of the law.

New York City officials provided Skift with an example of a property they found on Airbnb that the city recently shut down. A three-family home on the 500 block of Greene Avenue in Brooklyn was vacated for overcrowding following an inspection by the city. Inspectors found inadequate exits and no sprinkler or fire alarm system. It was crowded, too: The home was occupied by 44 guests.

The ugly

The New York’s illegal hotels market pre-dates the arrival of modern vacation rental websites. Traditionally, a landlord or building manager replaces tenants with year-long leases with some Ikea furniture and a listing on an apartment rental website for a short-term stay. In some cases regular tenants start being forced out to make way for by-the-night clients or leave in frustration.

“It’s not something you signed up for,” city officials told Skift. “Not knowing who’s coming through the lobby door isn’t how people want to live.”

In extreme cases, the postal service stops delivering mail at the residence.

“The vast majority of Airbnb listings are multiple units by the same entity,” says Sarra Hale-Stern, District Office Director for New York State Senator Liz Krueger, who sponsored the legislation that made short-term rentals illegal. “It’s not Aunt Suzy going off to London for the month. It’s corporate entities doing it 12 months out of the year.”

For years, Airbnb’s most famous host was Toshi, who acted as a middleman for owners who needed someone else to shuttle tourists around, hand out keys, and manage listings. Eventually, the Toshi name turned too toxic and he was forced to change his operating name to Smart Apartments LLC, but the listings remained on Airbnb.

In October New York’s Office of Special Enforcement sued Smart Apartments for operating more than 200 illegal short-term rentals in more than 50 buildings. The action against Smart Apartments points to a new tactic the city is using. “With Toshi, they’re looking at online false advertising as part of their lawsuit,” says Hale-Stern. “Consumer protection law is a new angle and it will be interesting to see where this takes them.”

The city has an injunction keeping Smart Apartments from operating or advertising, and it’s seeking both penalties and $1 million in punitive damages. Although the listings for Smart Apartments have since been removed from Airbnb, at press time listings that corresponded with addresses listed in the city’s complaint were still discoverable through Google.

Hantman couldn’t comment specifically about why Toshi/Smart Apartments operated for so long on Airbnb despite media attention and complaints from neighbors, but he did confirm that the listings were now off the site.

The challenge

In public interviews and private exchanges, Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky and other company leaders have either placed the blame on Airbnb’s users’ failure to read its Host Obligations or have made non-committal claims that they’re working with local authorities to iron out problems.

New York City and New York state officials say that claim is a one-way road. Hale-Stern says, “Airbnb has reached out a number of times to the city to convince them they should change the law to make their business model legal. Airbnb has not shown any interest whatsoever in being helpful. It’s shown no interest whatsoever in taking the illegal listings off the site.”

David Hantman says that it’s not that easy. “We are a platform that serves 34,000 cities,” he told Skift. “New York is a big one. We try to be as open as we can and we are trying to keep our hosts better informed. We want to avoid becoming legal advisors who are required to know the law in every market we operate.”

Airbnb’s first public foray into discussing its New York problem was on its new Public Policy blog. Hantman used it to respond to a New York Times story about Airbnb hosts receiving violations from the city. He wrote “in many cities, laws are confusing and unclear.”

“New York tried hard to stop the illegal hotel industry,” Hantman told Skift. “Laws that stop that make sense.” But that doesn’t represent the typical Airbnb host, he argues, “half of our people use the money they make to pay rent.”

A spokesman for Senator Krueger has a different take on this. “We see a big divergence in what people like Airbnb say and what the market really is,” he says. “That’s what they talk about when their CEO goes on CBS, but that’s not how their listings work. The bulk of their business is illegal hotels. It’s one thing for them to say on camera that their model is this nice thing, but it’s simply not true.”

Dwell Newsletter

Get breaking news, analysis and data from the week’s most important stories about short-term rentals, vacation rentals, housing, and real estate.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch