Inside the Clubby Business of Government Travel: A Skift Deep Dive

Skift Take

Chris Babb, founder of Washington, D.C.-based The Group Tour Company, remembers getting a letter from the federal government inviting him to bid on a major government travel contract.

Babb was intrigued by the dollar amount of the contract — it was large, especially for a small, family-owned business like his. So he began to read through the 100-plus page document he received, which went into the details of the contract, as well as the bidding and approval process.

Babb found the document nearly incomprehensible. “It was written specifically for someone who was already in the government contracting business,” he said. “As an outsider, you would have to basically hire someone who knew about writing proposals for government [contracts] to even get a foot in the door.”

For a small company, the cost just wasn’t worth it. Babb gave up.

This was years ago, but the experience was enough that Babb has since avoided government contracts completely — even when invites pop up in his email.

“I just hit delete,” he said.

Babb is not alone in his frustration. The government spends billions on travel each year through contracts with private companies, authorizing millions of government workers to purchase plane tickets, rent cars, book hotel rooms, and hire travel management agencies. But these contracts can be hard to come by — especially for an outsider like Babb — and many are concentrated among a small network of companies. Over the past two decades, some of these networks have gotten progressively smaller, as contracts become consolidated.

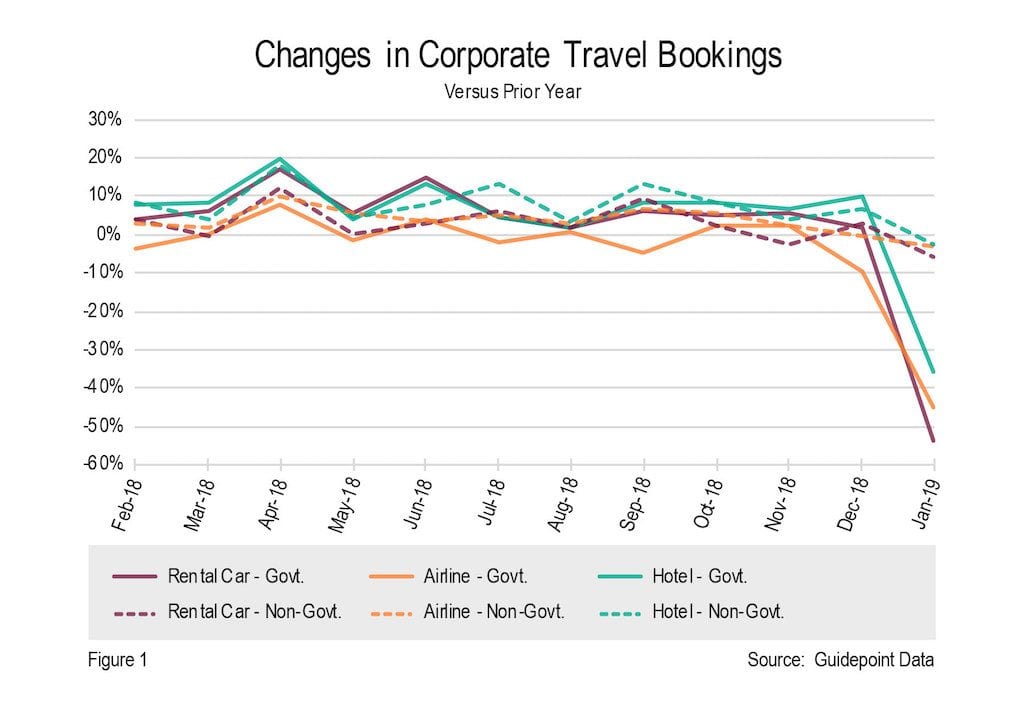

The most recent government shutdown in the U.S. helped shed light on this often overlooked sector of the travel industry. The federal government spent $33.6 billion on travel in 2016, according to the most recent data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, and during the 35-day political stalemate, much of this spending was put on hold. Rental car agencies experienced a 53.4 percent drop in transactions during the month of January compared to the year before, while airlines experienced a drop of 45 percent, and hotels 35.6 percent, according to a corporate travel report from data firm Guidepoint.

“Overall, public sector travel experienced the largest year-over-year decrease in spend of any of the 34 economic sectors tracked,” the report stated.

This matches up with news that came out at the time. In January, Delta reported a revenue loss of $25 million for the month, due to the fewer number of government workers traveling for work or leisure. In February, Southwest Airlines estimated that the government shutdown would reduce first quarter earnings by $60 million, in part because of the number of government travelers put on hold.

And it was not just airlines, hotels, and rental car agencies that felt the sting. Adtrav, a travel management service that does about 30 percent of its business with government agencies, saw its government portfolio cut in half during the shutdown, according to Adtrav CEO Roger Hale.

“We had a bunch of customers who pretty much said, ‘We just can’t travel, we don’t have any funds,’” Hale said. “While the government was shutdown, if you look at our whole government portfolio, I think we ended up being down about 50 percent across all of them.”

A Small World

And yet, despite the importance of government travelers to the industry, the government travel system is still largely unknown to outsiders.

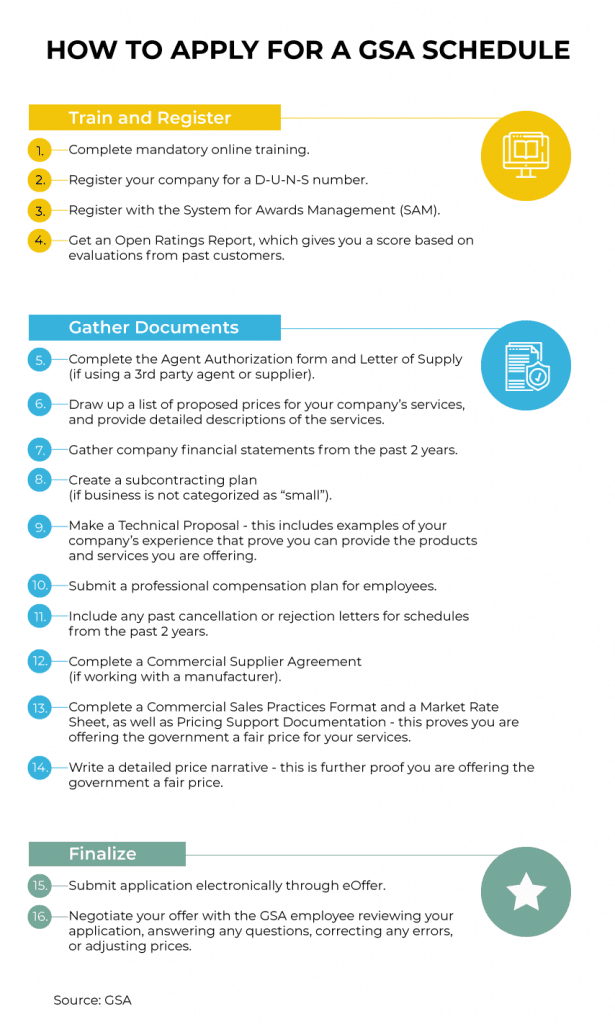

In part, this is because the world of federal travel is quite small and self-contained. In order to work with the government, companies must undergo an approval process, overseen by the General Services Administration (GSA), the federal branch that manages public sector travel and other services. After answering a wide range of questions, qualified companies receive a CAGE code — standing for Corporate and Government Entity — giving them the GSA stamp of approval. Once a company has this code, it can then bid on short-term contracts.

Companies that want longer, more lucrative contracts, however, need to undergo a second and much lengthier approval process. If approved, they will join a short list of other heavily vetted companies — called a GSA schedule — and will finally be eligible to bid on larger, multi-year contracts.

“The GSA [schedule] is a step above. It’s not so much an endorsement — it’s a listing. You’ve achieved your CAGE code, and after that, you go in and say, ‘I’d like to be able to be put on the GSA list,’” explained Bruce Boillotat, former government liaison for the Baltimore-Washington chapter of the Business Travel Association, a trade group focused on corporate travel.

"It’s basically a hunting license," Hale said of the GSA schedule. "It's not a contract to actually get any business. It’s basically saying you meet these minimum standards and you’re free to hunt and go out and call on federal agencies."

The Big Players

But of the thousands of companies with CAGE codes, only a small number actually make it onto the GSA schedule.

Take travel agent services, for example. Of all the travel agencies that have likely been approved to work with the government, only 23 are listed on the GSA schedule. Out of this 23 one big name jumps out: CW Government Travel, the government side of corporate travel management company CWTSatoTravel, which has by far the largest presence in the space.

In 2017, CWT recorded a whopping $309.8 million in sales through the GSA, while the next highest on the list, Adtrav, recorded only $3.3 million. Out of the 23 companies, the majority had sales in the thousands of dollars, while 6 companies - BCD Travel, El Sol, MIT MNN, Rio Grande, Rodgers, and Travel, Inc. - had zero dollars.

For a full list of the companies on the schedule, and their sales, check out the chart below:

In part, this is because CWTSatoTravel has been working with government agencies for decades. In 1989, when Congress first required federal agencies to compete their travel requirements, the company won one of the first contracts, with the Department of Defense, an agency with one of the largest travel budgets across the federal government.

It also has a heavy presence on the civilian side, contracting across multiple agencies.

“CWT runs a site called FedRooms,” said Richard Markus, referring to the U.S. government’s official hotel program. Markus serves as the vice president of programs and education at the Baltimore-Washington chapter of the Business Travel Association. “The GSA outsources the entire hotel booking arm to CWT, to manage through this site called FedRooms," he said. "They’ve had it for a long time.”

“It’s that long history and the fact that CWTSatoTravel focuses on meeting government travel requirements,” said Nicholas Vournakis, president CWTSatoTravel, of how the company gained such a presence in the space. “We train our personnel on the various laws, policies, and regulations on government travel and design our processes — centrally billed accounts, reservations, ticketing — around those requirements.”

Concur is another major player. In 2013, Concur became the sole travel and expense technology provider for GSA's updated electronic travel services system (called ETS2), which processes the travel of roughly 90 civilian agencies, an estimated $1.5 billion over 15 years. CWT contested this immediately, however, and SAP Concur was only the sole provider for 30 days.

SAP Concur currently has task orders for 36 federal agencies, which collectively provides travel and financial management services for over 70 agencies.

“We’ve got a very large implementation covering the civilian side of the federal government that’s been running for several years,” said Dave Ballard, senior vice president, public sector, of SAP Concur in an interview with Skift. In addition, the company has several active and pending contracts with the Department of Defense.

What are the benefits?

The arduous approval process to get on the GSA schedule acts as a buffer, keeping out many companies that do not have the time or resources to undergo it.

Government agencies are required to use small businesses for 23 percent of their overall contracting dollars, split up between different sectors, with travel being one. Small companies, veteran-owned companies, and minority-owned companies even get extra "points" for their status - but those points only go so far. The way the application and bidding system is designed makes it extremely difficult for outside companies to get in, and government agencies frequently fall short of their small business goals.

"Even though we’re a family-owned, small business enterprise, and we would have gotten points for that," Babb remembers, "the man hours and the cost just meant it wasn’t worth the hassle."

“It’s a rather byzantine process,” Markus said. “[The government] need[s] to collect a ton of data, some of it would be considered pretty confidential. They don’t want to approve a vendor that disappears or can’t come through. So they request all kinds of financial statements and examples of contracts with clients and those kinds of things. And a lot of companies don’t necessarily feel comfortable sharing that stuff with anyone.”

So it begs the question: Why go through with it? The first and most obvious reason, of course, is that the contracts can be very large, often encompassing entire agencies. For some businesses, the steady sales more than makes up for the hassle.

“If you know how to do the business, it’s a nice addition — it's like having any account,” Adtrav’s Hale said. “And the nice thing is, they’re large accounts. Another account we have is the Department of Energy, nationwide. So that’s a lot of people doing a lot of travel. So the volume there makes it attractive to have that business.”

Markus put it a little more succinctly. “I don’t know if there’s any bigger purchaser of anything than the U.S. government,” he said.

Apart from the size, government contracts can add some much-needed stability to a business in the travel sector, allowing it to diversify.

“The government business is not subject to the economic cycle like corporate business is,” Hale noted. “So it’s a nice offset. Like in 2007 and 2008, when the economy was going down, our government business was pretty steady. So that’s from my perspective why we pursued it.”

increasing Consolidation

Yet some of these contracts are going to fewer and fewer companies, with a handful of big names winning a large percentage of them.

In 1999, when online booking became popular, the GSA began to alter its travel system to keep up with a changing world. Previously, it had done statewide contracts — now, as it gradually took its operations online, it shifted to nationwide contracts. This opened up the bidding process to a wider group of companies, but it also paved the way for consolidation later on.

For instance, one reason CWTSatoTravel has such a presence in government travel is that it bought part of the competition. Up until 2006, CWT and SatoTravel were two separate companies, competing with each other for government contracts. But in 2006, “CWT acquired Navigant International, Inc., which had previously acquired SatoTravel. At that time a new M&G Division was formed from the CWT and SatoTravel government teams,” Vournakis explained.

At the same time, some government agencies began to increasingly favor an embedded contract model. This means that large, established operators like CWTSatoTravel and Concur would be more likely to win contracts, but they could choose to give out some of that business to subcontractors. As the GSA has continued to refine its online travel system, embedding has become the norm, according to Hale.

“Now you basically just work with Concur and CWT,” Hale explained. “There is a much bigger appetite now for federal agencies to use the embedded model as opposed to contracting separately for their services.”

Of course, big companies like CWTSatoTravel and SAP Concur are encouraged to use subcontractors. In fact, while applying to get on the schedule, these companies must create a plan detailing how they will use smaller companies as subcontractors. However, this plan is just that - a plan - and in practice, it is up to the larger company's discretion when, why, and to whom it will give business.

This means that even companies that manage to make their way onto the GSA schedule might not get any business as subcontractors. Take the list of 23 travel agencies for example - 6 of those companies made no sales at all, despite being on the coveted schedule.

“There’s still some opportunity out there, but the vast majority of federal agencies are using the embedded model for their travel solutions. There’s some small commissions that some folks have, but the opportunity is much less. There’s a lot of those companies on that schedule that really don't have any business.”

For many, the arduous approval process just may not be worth it when chances for business are so slim.

“I think the opportunity is limited for a new entrant to come in and secure a bunch of business. And the process to get on the schedule is laborious. It’s very laborious. It’s not rocket science, it’s just long and hard.”

Department of Energy networking summit, 2018. One of Adtrav's largest contracts is with the Department of Energy. Credit: Department of Energy

hundreds of Regulations

Not only is the approval process so difficult, but working with government agencies poses unique challenges. Companies are tied to stringent rules and regulations, and not all have the capacity to handle it.

“The thing about government is, it is its own discipline,” Markus said. “There are reasons that not every company does government, because it’s really complicated.”

“The biggest challenge is working within a very large set of regulations to follow,” said Concur’s Ballard. “And you’ve also got a very large organization. Whether it’s civilian or defense, you’ve got literally millions of folks that you’re trying to keep compliant against a set of regulations that’s often hundreds and hundreds of pages long.”

In this way, the difficult approval process can serve an important protective purpose. A lot of companies are just not set up to handle the extra work involved.

“When you’re dealing with the government, the penalties for failing to be compliant are significant. So you’re really protecting both the traveler and the employee," Ballard said.

“These folks are highly demanding, and you must fulfill their expectations,” Boillotat added. “If you do not, you will not keep them for a long period of time, and you will lose your reputation within the government sector immediately. Because no matter how big our government is, it is probably one of the smallest communities you will ever know in your entire life.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated the sales figures for CWT and Adtrav from government travel contracts for 2017. CWT booked $309.8 million in sales, and Adtrav $3.3 million.