How Artificial Intelligence Determines Which Airline Stories Go Viral

Skift Take

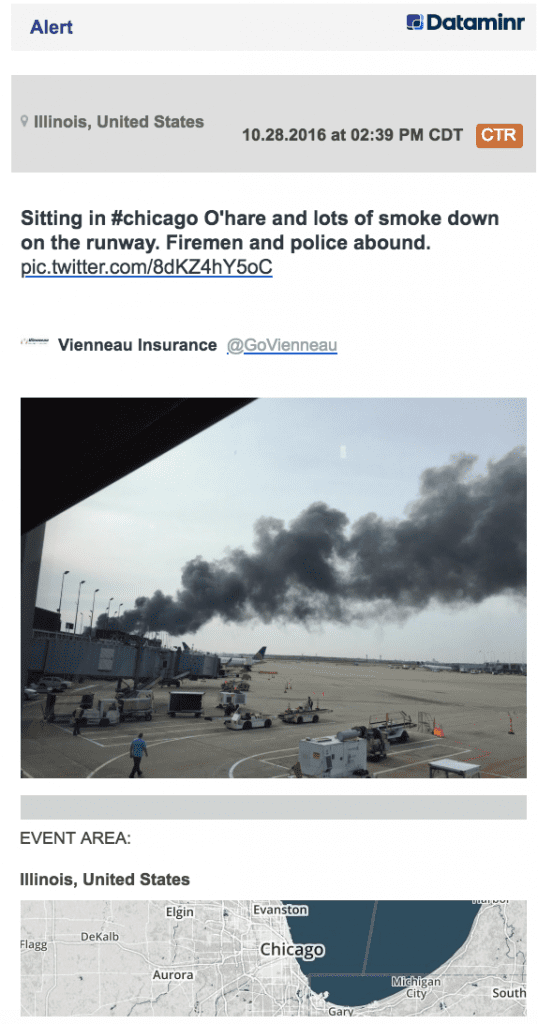

Early one afternoon in October 2016, CBS News correspondent Kris Van Cleave was taking the day off, having brunch with three friends in Los Angeles, when his phone began pinging. With increasing urgency, colleagues were sending a tweet, showing a smoldering American Airlines aircraft at Chicago O'Hare. They asked, what did he know?

He reached American Airlines spokesman Ross Feinstein just after 161 passengers and nine crew members safely evacuated from the burning Boeing 767-300. Soon, Van Cleave filed a basic story about an incident the NTSB would later say was an uncontained fire in the airline's right engine, caused by a failed turbine disk. Pilots aborted takeoff when the plane reached reached 154 miles per hour, making this among the more serious U.S. incidents of the past decade.

A few years ago, his quick reporting might have constituted a major scoop, but this day, Van Cleave was keeping pace with competitors, most of whom learned the news as he did. Rather than acting on a tip from a viewer, or a top-secret airport source, they received an alert from Dataminr, an artificial intelligence-driven platform that monitors tweets and other media to provide early-warnings to brands and newsrooms.

Using a secret algorithm — no one is sure how it works, and the company shares few details — Dataminr picked up on social media chatter from O'Hare, and alerted subscribers, including American's Feinstein, who said, "my phone was going off like you wouldn't believe." Feinstein said Dataminr's alerts gave him "about a minute or two" head start before he heard the news through official channels. "Social media just moves so much faster than someone can type an email or make a phone call," he said.

In this case, Dataminr provided a valuable service. But the platform is changing how airline corporate communications departments interact with journalists, and how reporters decide what becomes news. For every newsworthy story flagged by it, including crashes, reservation system failures, or even celebrity meltdowns, it calls attention to thousands of issues that probably should not make news, like a passenger tweet storm about an airplane cabin that is too hot or too cold, or a fender-bender on an airport roadway.

“One of the great things about Dataminr is that it will flag you to something that may be happening,” Van Cleave said. "The thing that is challenging about Dataminr is that it will flag you to things that might be happening. It can get a lot of people spun up when people see this Twitter alert that ‘my plane is on fire,’ when it reality it is not.”

But journalists and airline representatives have no choice. Dataminr is driving the conversation, they say, and they need to be part of it.

"It's a system I love to hate and I wish I didn't have to use it,” Feinstein said.

Dataminr alerted clients just after an American Airlines Boeing 767 suffered an engine fire in October 2016.

Making Sense of the Firehose

Dataminr began in 2009, founded by three former Yale University roommates, who figured they could use advanced math and analytics to make Twitter more manageable. All the news was there — people often call Twitter a "firehose" of information — but it's difficult to make sense of it, at least quickly.

Dataminr's service became popular among governments and intelligence services, who could use it to monitor hotspots — it can provide early news on terrorist attacks — and bankers, who could use it to guide trading decisions. Four years ago, in an early example, Dataminr found a Tweet from an expert alleging Home Depot had been the victim of a credit card breach, allowing its subscribers to react on public markets before the company's stock dropped.

"It's about knowing first, so they can act faster," Jonathan Barrett, Dataminr's managing director for Europe, said in an interview.

Traders remain important clients but Dataminr has not been so cozy with some governments since 2016, when Twitter, also Dataminr investor, cut off access to U.S. intelligence agencies, according to a Wall Street Journal report. Still, Dataminr remains a favorite among its investors, and in June closed a $392 million funding round at a $1.6 billion valuation, more than twice its 2016 valuation, Axios reported.

Now, it increasingly sells to newsrooms — about 450 news-gathering operations use Dataminr worldwide — and to corporations, with American, Delta Air Lines, United Airlines, and Allegiant Air among its customers. (A spokeswoman for Dataminr declined to say how many airlines worldwide use it services, nor name them.)

At Delta, corporate communications has used Dataminr for about a year, spokesman Michael Thomas said. He declined to detail how the airline uses it, but said, “It is just one of the many tools in our toolbox to be monitoring what’s going on, not only at Delta but across the industry.”

American began subscribing to Dataminr in early 2016, after corporate communications staffers started receiving phone calls about relatively minor events, Feinstein said.

“We would have some sort of disruption and we would have 10 media calls within a matter of minutes," Feinstein said. "We couldn't figure out what was going. We said, ‘Where are you getting this from?' The timing was always odd. That's when we realized, this was Dataminr.”

Over the past two years, Feinstein said Dataminr has flagged many useful tweets for Feinstein and his colleagues, including:

- American 1090 in March 2017, when a flight from Chicago to Miami diverted to Jacksonville, because of reports of smoke in the cabin. Dataminr found a tweet from a user with 44 followers, who had written, “Flight attendant attending to smoke. Plane headed to ground at speed. No word why." He posted a picture of a cabin crew member with a fire extinguisher.

- An early report on Cubana Flight 972, which crashed after departing Havana's airport in May, written in Spanish by a journalism student with 338 followers.

- Reports of a serious security situation developing in Seattle in August. One woman, with 596 followers wrote, "Pilot says a Verizon employee hijacked another plane." The post was close to accurate, with one exception: The employee worked for Horizon, the airline. The employee later crashed the airplane.

- A post by rapper YG in August. He uploaded a profanity-laced video to Twitter saying he had been kicked off an American flight from Los Angeles to New York because of racism. American said it was because he was drunk. (A month later, Feinstein also learned through Dataminr that another rapper, Wale, had accused the airline of racism.)

Minor Stories Become News

All of those incidents might have made news a few years ago, though it could have taken a while for reporters to learn about them.

But Dataminr also finds stuff reporters might not have known about and may not constitute news. Local reporters might call Feinstein, or another airline's representative, to ask about something as mundane as a go-around, a diversion or an unscheduled landing. Flyers may get spooked, but at an airline as big as American, with 6,700 flights a day, those events happen more often than most passengers realize.

"The national reporters understand that planes divert and have mechanical issues," Feinstein said. "Local media outlets also subscribe, and anything in aviation will drive media attention these days."

Often, local journalists ask about incidents that might be noteworthy to people on the plane, but probably not to others.

Often, local journalists ask about incidents that might be noteworthy to people on the plane, but probably not to others.

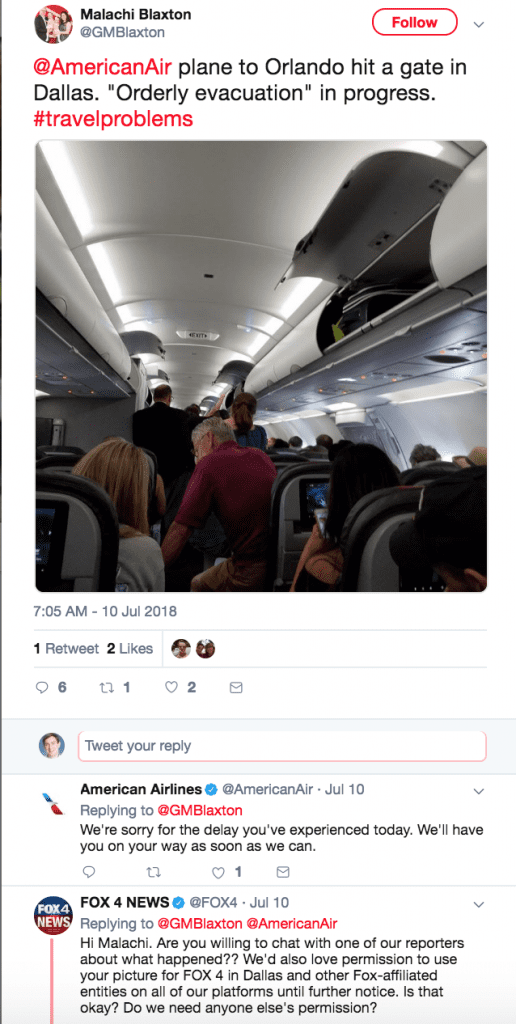

In July, for example, an American Airlines flyer named Malachi Blaxton shared that his "plane to Orlando bumped a gate in Dallas," and posted a picture of passengers getting off the plane, normally, through the front door.

When Dataminr flagged his tweet, it had received one retweet and two likes. But within 19 minutes, the local Fox affiliate asked for an interview, along with permission to use the photograph. NBC and CBS affiliates followed.

News organizations don't just use Dataminr for aviation stories. But the public has a vigorous appetite for airline news, and Feinstein and Van Cleave say newsrooms may rely more on Dataminr for aviation news than for other sectors.

Van Cleave has experience. While airline stories are about 60 percent of his beat — the rest are general transportation pieces — they account for a disproportionate number of his Dataminr alerts.

"People don't take to Twitter about a traffic jam unless it's an epic traffic jam," Van Cleave said. "But there is something about an airplane where it is about the only place where two people get into an argument or a fight and it becomes national news.”

Still, Dataminr's Barrett said the company makes no apologies for flagging items that may not have news value.

"The very fact that someone wants to share this in the public domain means it is no longer a secret," Barrett said. "What they are able to do, though, is to reach a far wider audience than perhaps they could do in years gone by when they couldn't have the same platform."

By subscribing to Dataminr, Barrett said, airlines and other corporations know what others are saying about their brands.

"We are more connected now than we have ever been," Barrett said. "That gives the platform for people to share information, whether they think it’s important or not. Things can go viral and our job as Dataminr is to provide the relevant information to our customers so they can make an informed decision to act in their best interest."

Intelligence Gathering

Airlines also use Dataminr information to glean information about cities and airports they serve. If they set alerts right, they can follow nearly every aviation incident in the world, in real-time, Allegiant Air spokeswoman Hilarie Grey said.

“It is a little bit addictive,” said Grey, who monitored the stolen Horizon Air plane in August while attending a Stevie Wonder concert.

It can be useful to an airline's operation, too. Allegiant uses Dataminr during hurricane season, and sometimes tweaks plans at Florida airports depending on what it learns. If, for example, local officials have ordered emergency evacuations, Allegiant can guess the city’s airport will close soon, and perhaps stop flying sooner than planned.

“You can pick up on when Dataminr says, these three counties are going to order evacuations at a certain time,” Grey said. “It gives us more inputs and more real-time information."

Grey also used Dataminr in August to learn about a lockdown at Albuquerque’s airport, when a man threatened to kill himself inside an airport shop. Another time, she shared news internally about a suspicious package at Los Angeles International, which, while ultimately harmless, might have kept some passengers from arriving to the gate on time.

That also happens at American, including in January 2017, when a gunman opened fire at Fort Lauderdale’s airport. Feinstein, reacting to a Dataminr alert, asked the airline’s operations center if it had heard anything. “Nope, all quiet,” came the reply.

Feinstein then called American's general manager in Fort Lauderdale, who said the same. “Finally a few minutes later our GM calls back and says, ‘We have a major issue here, and we are lockdown.”