Smithsonian’s new exhibit explores three centuries of travel navigation innovations

Skift Take

Looking back on how much travel has changed in just 100 years is a humble reminder of how temporary the current state of our industry is and how much room for innovation still remains.

In the age of hand-held GPS devices, navigating by the stars may seem quaint and irrelevant. So it may come as a surprise that it took hundreds of years to develop the tools needed to find our way across oceans, through the air and into deep space.

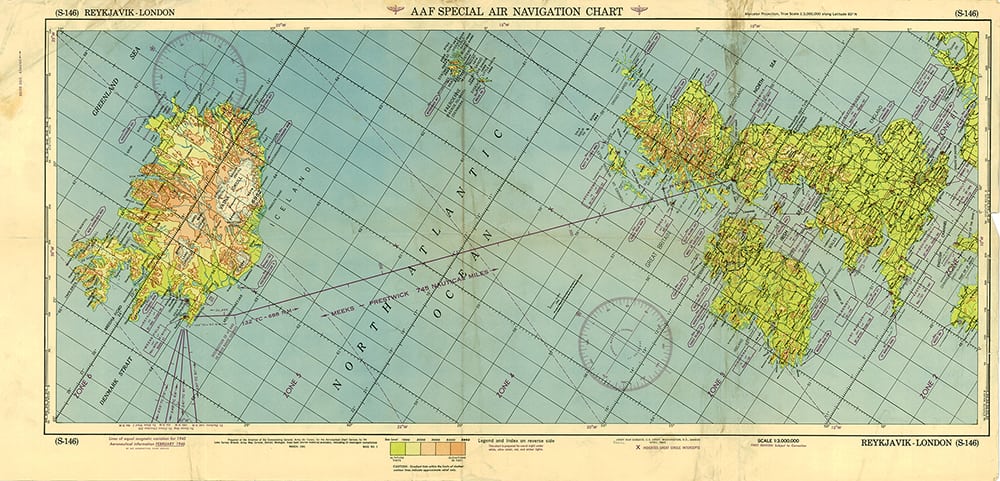

On Friday, the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum is opening its first major exhibit focused on navigation. It includes instruments that aviator Charles Lindbergh used to learn celestial navigation and the clock he used during his milestone trans-Atlantic flight — along with much luck — to help make his way from New York to Paris in 1927.

The museum pulled together stories and objects fro