The State of Airport Security in a TSA PreCheck-Packed World

Skift Take

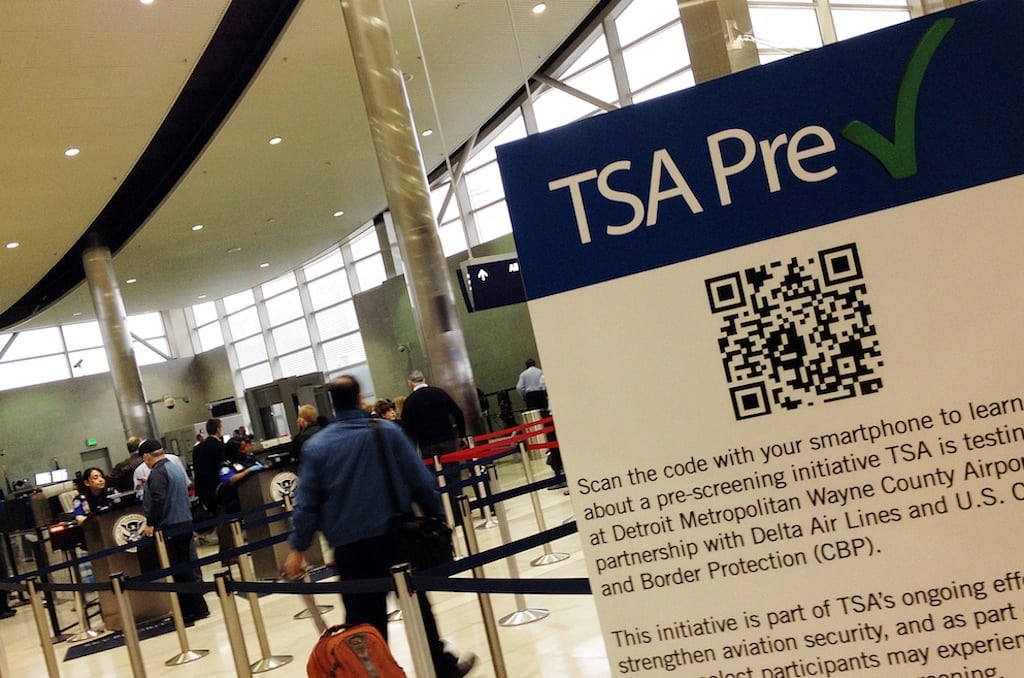

When the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) launched its PreCheck program in October of 2011, many frequent travelers breathed a sigh of relief.

Since The TSA’s inception in November of 2001, the agency has been slowly restricting items allowed through the airport checkpoint – first it was liquids over 100mL, then it was shoes, then it was multiple batteries and any host of oddly-specific-yet-surely-credible-threats.

PreCheck was supposed to be a respite from that action, a way of rewarding frequent travelers for their numerous trips through the airport checkpoint and speeding up security for passengers across the board. Those who were accepted into the program and paid an $85 fee — or who were grandfathered in from a Customs and Border Protection (CBP) program — were allowed a faster, more efficient security experience.

Membership in the PreCheck program brings a host of benefits including the ability to keep electronics and liquids stowed while going through security as well as relaxed restrictions on what can be worn through the magnetometer. And to a large degree, it’s been a huge success. The agency now operates expedited checkpoints at 118 airports with around 400 dedicated lanes. Over 400,000 people have signed up for the program at 26 airport and 275 off-airport locations.

Growing Pains

With growth, however, comes teething problems. Many passengers who sign up for the program expect shorter lines for dedicated passengers, but the TSA doesn’t exactly offer that service. Instead, the value proposition presented by the agency is expedited screening, suggesting the lines will go faster based on the limited screening steps with no guarantees on the length of the line.

The agency also mixes randomly selected “low-risk” passengers into daily PreCheck lines, an effort to relieve mainstream security flow and do some low-level marketing. Often, the passengers unfamiliar with the line’s benefits end up disrupting the flow of the line, much to the chagrin of seasoned travelers.

At its worst, PreCheck can be more of an inconvenience than an enhancement. Many stories have crossed my desk over the last two years lamenting a long PreCheck line or a mismanaged queue.

As extra cycles have gone into the program, though, many of the bottlenecks have eased. At Chicago’s Terminal 2, where the morning PreCheck line used to snake around the premium checkin, there are now multiple lanes funneling passengers efficiently through security. There’s enough visibility in the system now that I can book an American Airlines ticket through British Airways and still get PreCheck credentials. And despite the “randomness” built into the system, I haven’t been excluded from expedited screening in my last six months of travel. I’ve seen similar stories of smooth checkpoint passages from my traveling peers.

Growing Acceptance

In Chris Elliott’s column on USA Today this week, he concludes that the traveling public has just given up and just stopped complaining. I believe that’s true to some extent — but I also think that the system is starting to settle in. Speaking at the Aspen Security conference last week, John Pistole, the agency’s administrator pointed out that despite cutting their staff 7% this year, wait times at checkpoints have actually decreased.

This isn’t to say that all things are copacetic in the PreCheck world. Numerous colleagues around Newark International report that the lane management in Terminal A is nothing short of a fiasco, and not a day goes by without a loquacious tweet from an unhappy passenger. Adding to the negative public sentiment, the agency just ratcheted up the fees that it collects on each passenger ticket, a move required by congress but lambasted by multiple news agencies, despite that the money is going to fill non-travel budget shortfalls created by Congress.

Much like O’Hare however, I expect Newark and the media outrage to quietly settle.

Helping the cause will be the continued expansion of PreCheck to a wider consumer base and better education among traveling passengers. The agency’s Ross Feinstein tells me that looking forward, as PreCheck passengers swell over the coming year, so will the lanes equipped to accommodate them at the airports. The volumes of random passengers assigned to the expedited lanes, conversely, will start to fall.

We’re only one more “credible threat” away from another disruption in the process though, as proven by this month’s restriction on mobile devices from foreign airports.

“Since we are a risk-based intelligence driven organization, it’s all based on what the latest intelligence tells us,” Mr. Pistole said in his Colorado talk. “So what we have to be focused on is how we can mitigate or manage risk without adversely effecting the global economy. As long as the intelligence says that there’s a persistent clear threat we will keep those [security measures] in place.”

As this speed bumps continue to appear, there will no doubt be delays in the restoration of humanity to the security screening process. But on our current trajectory and with improved technology, we’re inching closer.