Why Do National Airlines Still Exist?

Skift Take

For three consecutive winters beginning in 2010, executives at Budapest's airport watched daily to see if their largest tenant, the Hungarian national airline representing more than 40 percent of its passengers, would go bust.

The carrier, Malev, started flying in 1946 as Maszovlet, and for decades as a government-owned enterprise, it flew mainly Soviet-built jets on short-haul routes, before expanding in the 1980s with Boeing aircraft. For a while, its model worked well enough, but the rise of democracy changed much in Hungary, including at the airline, which was forced to compete with nearly every national carrier in Europe.

As it sought to become more nimble in the 1990s and 2000s, Malev tried to privatize but never could make it. In 2010, with the airline struggling amid the European financial crisis, Hungary took control of 95 percent of Malev to try to save it. It stemmed the trouble, but caused another problem: The European Commission ruled it an illegal subsidy, ordering the airline to repay the state. It could not.

By early 2012, Malev was gone, and government ministers asked executives at Budapest's airport how to proceed. Perhaps they could find investors for a replacement? In other countries, including Switzerland, national airlines have disappeared one day, replaced the next by a doppelganger with a similar name and brand.

Malev, the Hungarian national airline, operated Boeing 737-600s jets like this one before it went out of business in 2012.

“We gave them the best advice we could,” said Kam Jandu, now the airport’s chief commercial officer. “We said, ‘There is a reason Malev is not existing anymore. There was no marketplace for a national airline. If you want to throw money down the drain, you can do that.'"

Other countries may face similar questions soon, as the timing is likely ripe for more airline failures. The world cannot stay out of another recession forever, and even if the economy surprises, carriers must adapt to higher fuel prices one major airline CEO recently called "the new normal.” Plus, the International Air Transport Association, a trade group representing the world’s airlines, warned recently the “looming prospect of a global trade war is casting a long shadow” on travel demand.

If airlines suffer, governments may need to ask if there's still value to having a national carrier other than patriotism or pride. And they may wonder whether it still make sense to prop up airlines as more countries open their skies to new entrants and foreign carriers.

The most powerful national brands should be fine. Airlines like Lufthansa and British Airways long ago separated from governments, and their home markets have robust demand. But elsewhere, from South Africa to India to Nigeria, politicians may need to ask whether it's good public policy to pump taxpayer cash into airlines, directly or indirectly.

Most governments don't want to let go. But some free-market proponents, like Antonis Simigdalas, who founded Aegean Airlines in Greece two decades ago, effectively putting the decades-old national airline out of business, say it's an exercise in futility.

“If the choice was whether I wanted to have a national airline and pay a shitload of taxpayer money just to maintain the flag on airplanes compared to having someone else come and fill the void, I’d choose someone else,” he said. “If nations want their flags to be carried, they can do it in many other ways.”

CARRY YOUR FLAGS TO THE WORLD

The idea of a flag carrier came about in 1944 at what is now called the Chicago Convention, which featured representatives from 54 countries, said Samuel Engel, head of the aviation practice at the consulting firm ICF, and an occasional consultant to national airlines. At the time, he said, the convention defined a flag airline as “substantially owned and effectively controlled by citizens and nationals of the country.”

Most countries had one. Some had two. The idea was simple: These airlines carried the flags of their countries abroad, and often received government support, as well as monopolies or near-monopolies on key routes. They didn’t need to make money, because as another consultant recalled, a nation could not be considered legitimate until it had collectible stamps and a flag carrier.

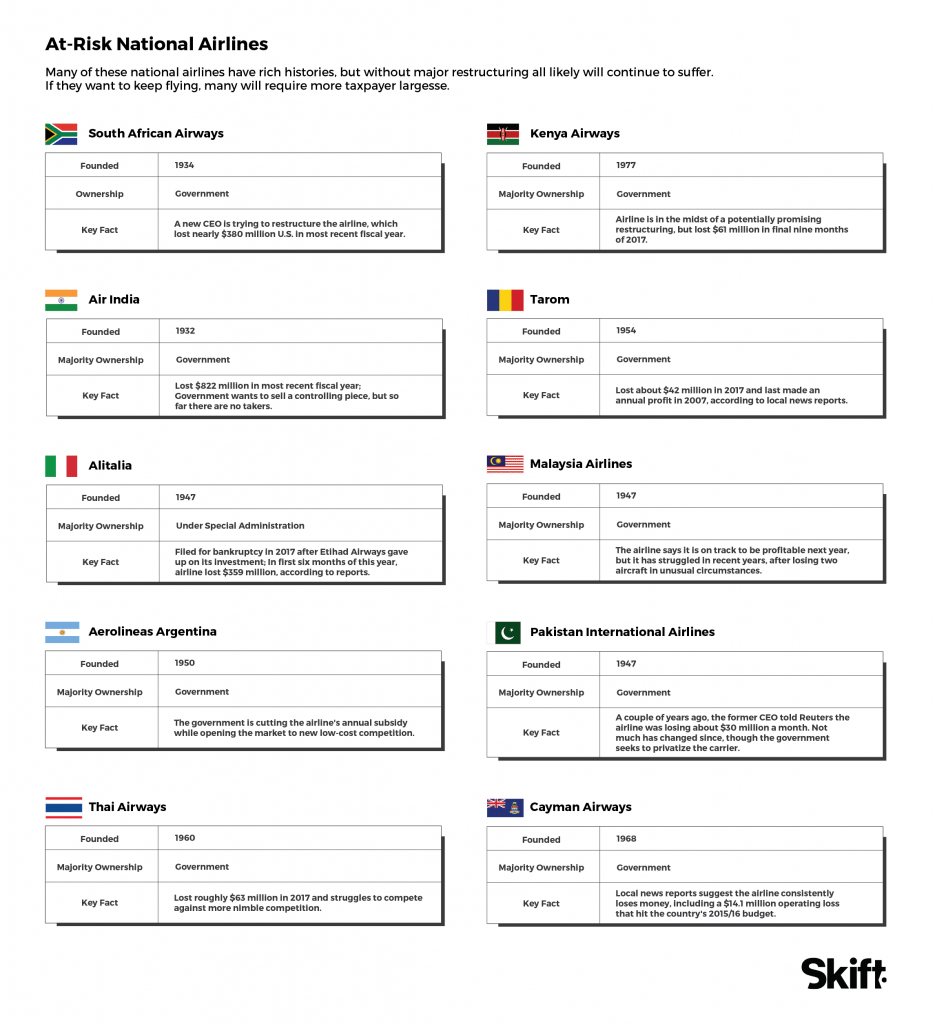

(Click to enlarge chart items)

The term no longer means much, since technically new entrants like EasyJet are flag carriers from the United Kingdom. But it's nonetheless often used to describe airlines, both new and old, that dominate their nation’s air routes.

In some cases, these airlines are fully government-owned, while in others a government owns shares. Some national carriers are independent, but may benefit from infrastructure spending or lower taxes on passenger tickets or fuel.

While some national carriers thrive, many more have become bloated and inefficient. They're often less likely than market-driven carriers to cut loss-making routes, and they usually don't innovate as much as newer airlines. In many cases, they're slower to adapt to changing trends, whether on product, such as seats or lounges, or with digital tools. Perhaps worse, they can be complacent when a new entrant — perhaps a low-cost carrier — enters their markets.

Yet many governments continue to bail out national carriers. Politicians sometimes argue an airline is an extension of the foreign office, or an "embassy with wings.” They note that, though the era of powerful national airlines might be waning, some have grown, improving their nation’s stature. This group includes Etihad Airways, Emirates, Qatar Airways, and Turkish Airlines.

“The government should be involved in making sure flag carriers are successful,” said Orhan Sivrikaya, former executive vice president of commercial for Turkish Airlines. “The air transport industry is related to other sectors, and it is a multiplicative effect on other industries. For national strategy, it is important.”

Some countries, such as islands with major tourist-driven economies, assist national airlines for strategic interests, fearing if the carrier stopped flying, no new entrant would step in. Others support airlines more out of nostalgia or national pride, or because they always have: The French government owns about 14 percent of Air France-KLM, and though it has considered selling, for now it keeps close tabs on the company.

Bjorn Kjos, CEO of Norwegian Air, said he'd like to see the French and other governments get out of the airline business so the market can work. The government of Norway in June sold the last 10 percent of its shares in Norwegian's chief local rival, Scandinavian Airlines.

“Some countries have gotten to their senses and they are trying to get out of these legacy airlines,” Kjos said in a recent interview. “You don’t need it. It’s just a waste. You should concentrate on totally different things. They don’t need to own airlines.

Travelers Have Moved On

Among the ‘let the airline go out of business’ crowd, Hungary is often example No. 1 for why it’s best to let markets work.

Since airport executives knew Malev probably would close, they had contingency plans. They started by asking carriers like British Airways, Air France, and Ryanair to add capacity and routes to Europe's largest markets. The airlines, knowing Malev probably wouldn’t make it, already had analyzed opportunities, and many expanded in Budapest.

Within three months, Jandu said, the airport regained about 40 percent its lost capacity, and within eight months, 95 percent returned.

While the airport first relied on foreign airlines, Malev’s demise cleared room for a Hungarian upstart, ultra-low-cost carrier Wizz Air, which started flying in 2003 but grew rapidly after 2012. This June it took delivery of its 100th aircraft, and has said it expects to have 300 jets by 2026.

Wizz Air is not a perfect replacement, even though it can fly Hungarians nearly everywhere in Europe. It’s not a flying billboard for the country, and it doesn’t carry Hungary’s flag abroad like national carriers of yesteryear. Rather than feeling pride about flying a Hungarian airline, passengers might complain about limited legroom or fees for soda.

But for the most part, travelers have moved on.

“I would be lying if I said no one cares,” Jandu said. “The vast majority don't care. The average age of the travelers are quite young. They are not brand loyal. They don't have a preference. What's most important for them is a direct flight.”

That includes long-haul flights. For decades, nearly every large national airline within 12 hours of New York flew to John F. Kennedy International Airport, or wanted to — whether the flights lost money or not. Malev started flying to New York in 1993, canceling the route in 2008 when fuel prices spiked.

Budapest's airport sought another New York link, though with no national airline, it wasn’t clear how. It approached the three major U.S. carriers, but while Delta Air Lines and American Airlines had flown the route before, none were interested. (American this year started flying from Philadelphia.) The airport tried the largest Gulf carriers, which may stop in Europe to pick up passengers. Emirates considered but passed.

The solution came in an unlikely place. LOT, Poland’s national carrier, has had its own problems with its home market, and wanted to expand beyond its Warsaw hub, so it agreed to fly to New York four times a week and Chicago twice a week. (LOT also had suffered in the debt crisis, and took state aid in 2012 in accordance with EU rules.)

"People say, ‘If we are not going to have our own, we might as well have LOT,’” Jandu said.

This doesn’t surprise Simigdalas. After leaving Aegean, he helped rescue the brand of Greece's flag carrier, Olympic, serving as CEO of its stripped-down privately-held successor. But it wasn’t meant to be, and Olympic no longer exists as a standalone entity. It’s now a short-haul brand owned by Aegean.

Interestingly, without its national airline, Greece had its own problems securing year-round New York service. Eventually, the market resolved it: Emirates now flies from Athens to Newark.

“Markets are like thermodynamics,” Simigdalas said. “There is no void.”

Africa's Dilemma

Still, many politicians fear they live in countries where no other airlines, foreign or homegrown, would fill gaps left by a national carrier.

It's an issue in South Africa, where South African Airways consistently operates at a loss but keeps flying with government help. By one academic’s count, the airline has tried to restructure 10 times in the past two decades, with the latest attempt led by former telecommunications executive Vuyani Jarana, who promises to cut employees and loss-making routes. Still, in an interview in June, Jarana said it would be unthinkable to close the more than 80-year-old company.

“It still plays a very critical role in moving people across the continent despite its own financial problems,” he said. “Many people would say, well, ‘The market would take care of this,’ but just with the size of SAA — from pure people movement — it's not something the market could address overnight.”

Perhaps not, though many argue other carriers would fill gaps in a market as large as South Africa, so long as the government stepped aside. Earlier this year, 23 African countries, including South Africa, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Kenya, took a major step toward deregulation when they created a common aviation market. Europe’s common market, more than a quarter-century old, is a major reason Europeans have access to more airlines and lower fares for short-haul travel than three decades ago. (It's also why a Polish airline can fly nonstop from Budapest to New York.)

But 32 countries have not signed on, so it’s not clear Africa is ready to follow the European model. Many nations prefer to have their own national airlines.

“Over 50 African countries continue to dabble in the airline industry despite the continent's poor track record, mainly because a national carrier is believed to be a source of patriotic pride and economic status – both of which are very seldom borne out in reality,” said Sean Gossel, who teaches at the Graduate School of Business at the University of Cape Town.

One of those countries is Nigeria, which this summer announced plans to build another national airline, six years after the nation’s last one stopped flying. Nigeria Air will be 95 percent privately owned —and may be managed by Ethiopian Airlines — but it’s clear the government is driving it and wants its own national brand with a global reach. At a press conference in July, the country’s aviation minister said Nigeria Air could fly to China and India.

This obsession with long-haul flying is a typical symptom among national carriers with outsized ambitions. It’s true for South African Airways, even though the airline’s home hub, Johannesburg, is located at the southern tip of Africa, making it an inconvenient stopover for connecting passengers from other countries. It’s also a mile above sea level, an altitude that hurts aircraft range.

But despite the restructuring, South African is clinging to its international route structure, including Hong Kong, which Jarana said is not a top performer.

“It's our only entry today to Asia so we have to keep it,” Jarana said.

That’s a mistake, ICF's Engel said. He said he understands why some countries want nonstop ties with important cities, as many politicians believe they foster greater trade and higher tourism numbers. Still, he said, “there are cheaper ways to get a flight to Asia than running an entire airline.”

Engel said he recommends a country offers subsidies to a foreign airline to run routes the government wants served. South Africa might not get the boost of having its flag carrier abroad, but taxpayers win. “Plenty of airports and municipalities subsidize air service,” he said. “That doesn't mean that a town in West Virginia needs to start its own airline.”

Simigdalas is harsher.

“Why should there be a link to to Asia?" Simigdalas said. “It defies my logic. I am sure our colleague at SAA has his own reasons or he has significant pressures from political bosses or whatever. But I am sure if he were to ask private shareholders whether they would like to maintain loss-making routes in their network, I don't think they would say yes, unless you gave them a promise of profit in the future.”

A Hands-Off Approach Can Bring Success

Free marketers may never agree that governments should be involved in airlines.

But several countries have proven one model works. It’s the hands-off approach, where a government — which may or may not own shares — acts in the background to prop it up, but doesn’t meddle much in day-to-day operations. It helps if these airlines are located in places where operating an airline hub makes sense.

An airline that must be profitable on its own can be more nimble than the average state-owned or supported carrier. One success is Ethiopian, a government-owned enterprise that by most accounts is the only true global airline in Africa, with a network stretching from Beijing to Los Angeles to Sao Paulo. It has been so successful that other African countries are asking it to manage their airlines.

Ethiopian operates like a private company, albeit one its competitors say has access to perks, such as loans, that private airlines might not receive. According to Gossel, the University of Cape Town lecturer, "government employees do not enjoy party-political perks, route management is linked to the airlines’ international strategy, and management has focused on skills development.” Perhaps better, the country has invested in infrastructure and plans a new international airport that could accommodate as many as 80 million passengers per year, roughly as many as Los Angeles handles today.

Airlines in United Arab Emirates, Qatar, and Turkey also have been beneficiaries of government spending designed to help them. This largesse was a hot topic recently in the Open Skies spat between American, Delta, and United on one side and Etihad Airways, Emirates, and Qatar Airways on the other.

The three U.S. carriers accused the Gulf carriers of receiving tens of billions of dollars of interest-free government loans with no repayment obligation over several years, as well as government grants, capital injections, free land, and airport fee exemptions. The U.S. airlines, through a trade group, complained the United Arab Emirates was “spending tens of billions of dollars to build that infrastructure, which is grossly in excess of the capacity needed to serve Dubai’s local population.”

While that’s likely true, it may not be as scandalous as the trade group suggests. It's no secret many successful national airlines take government assistance, particularly at airports.

It happens in Turkey, too. Later this year, Turkey will open a new megahub in Istanbul after just three and a half years of construction. At first, the airport will be able to accommodate 100 million passengers a year, but future plans call for it to be expanded to handle 200 million.

It is part of a government strategy hatched a couple of decades ago to turn Turkish Airlines into a major global player. Over the period, the country deregulated its airline industry, opened its skies, and privatized the national airline. And though Turkey still owns 49 percent and has some veto rights, Turkish generally operates as a market-driven enterprise.

Simigdalas said he respects Turkey, because the country stuck to its strategy. Other politicians have ideas, but governments change, and national airlines suffer. “They synchronized all their policies and plans so they could develop a mega carrier,” he said.

That’s tougher than it sounds. Sivrikaya spent 22 years at Turkish Airlines, and now works as a consultant, helping carriers in developing countries. He recently finished a contract with Uzbekistan Airways, and though he had some success — he persuaded the airline to fly to New York — he said it was tough to persuade politicians to let the company operate independently. When ministers make decisions, rather than the CEO and an executive board, airlines suffer, he said.

“This is a big obstacle,” he said. “They have to deregulate the structure of the company.”