Interview: Designing for Millennials and the Future of Hotels

Skift Take

The future of hotel design might be on a smaller scale, but Yabu Pushelberg knows the design aspirations and expectations will be even greater than they have been before.

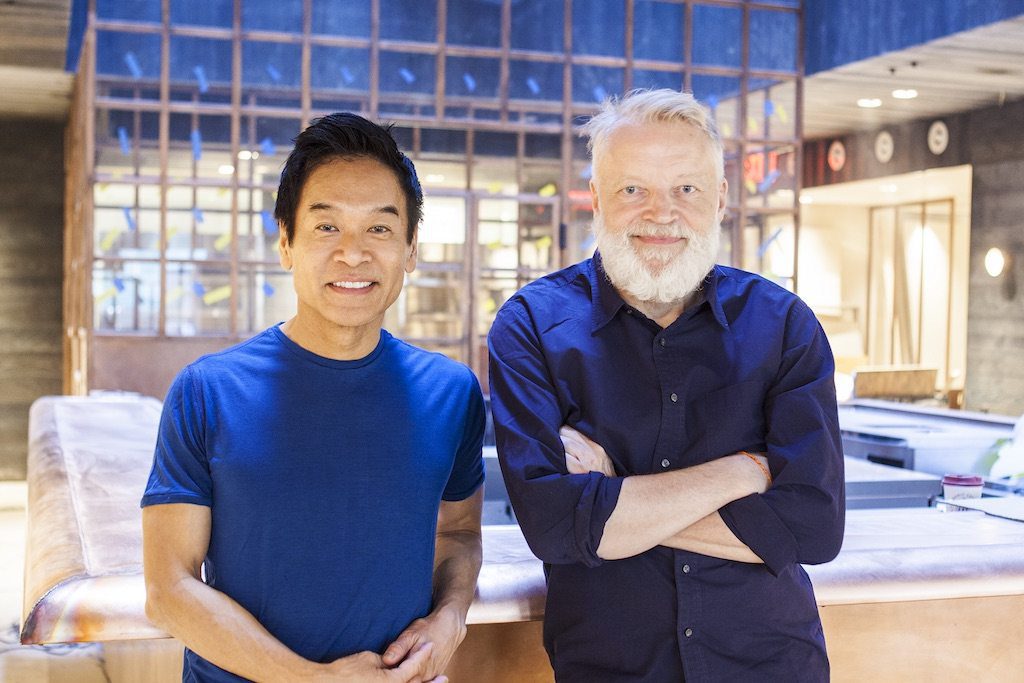

Toronto- and New York City-based designers George Yabu and Glenn Pushelberg have designed properties for some of the biggest names in hospitality for nearly 40 years. Their clients and brands include Ian Schrager, the Four Seasons, Park Hyatt, and the St. Regis, among them.

But their newest hotel project isn't being marketed as a luxury product. Instead, it's the 612-room Moxy Times Square, Marriott's answer to guests who want a hotel that doesn't forsake style for a lower price point. The property is scheduled to open later this month.

The property's developer, Lightstone Group, asked Yabu Pushelberg to design the hotel's guest rooms and public spaces. The Rockwell Group designed the hotel's dining venues, which will be operated by TAO Group.

The duo, founders of the eponymous firm that bears their last names, are known for their sleek, elegant, contemporary, and sophisticated designs. Translating that design aesthetic to a hotel with much tighter space constraints proved to be a challenge, but one that the two and their design team gladly wanted to undertake. Rooms at the Moxy Times Square range in size from 120 square feet to 350 square feet.

The micro-hotel concept is one that continues to flourish, especially in New York City. This year alone there have been the opening of Schrager's flagship Public New York, which markets itself as having "luxury for all" and had promoted room rates when it debuted at just $150 a night, although now the rates are often higher. And Pod Hotels, which already has two locations in the city, is planning to add two more — one in Times Square and another in Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

Skift spoke to Yabu and Pushelberg about the unique design challenges presented by micro-hotels, and where the future of hospitality design is headed. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Skift: You're both very well-known for your hotel designs for brands such as the Four Seasons, Le Meridien, Edition, and Park Hyatt, just to name a few. What was it like to work on a project like the Moxy Times Square, for a project that's not necessarily considered a traditional luxury hotel?

Glenn Pushelberg: We're actually very keen to do any project that has a reason to be designed and that can enhance the experience through design. What happens is you get pegged into the obvious categories: These are luxury products, these are luxury designers, and they do all those kind of five-star hotels, which is a wonderful thing