Skift Take

Medellin doesn't have massive casinos or beachfront properties to attract conventioneers but it is a city on the move that is becoming a model and beacon of hope for cities throughout Latin America and developed countries, as well.

When you wander around Medellin and mention to city officials and entrepreneurs that you are touring now-very-dead drug kingpin Pablo Escobar’s grave and other points of interest related to the city’s dark history, they tend to wince because they are now very much focused on “the transformation.”

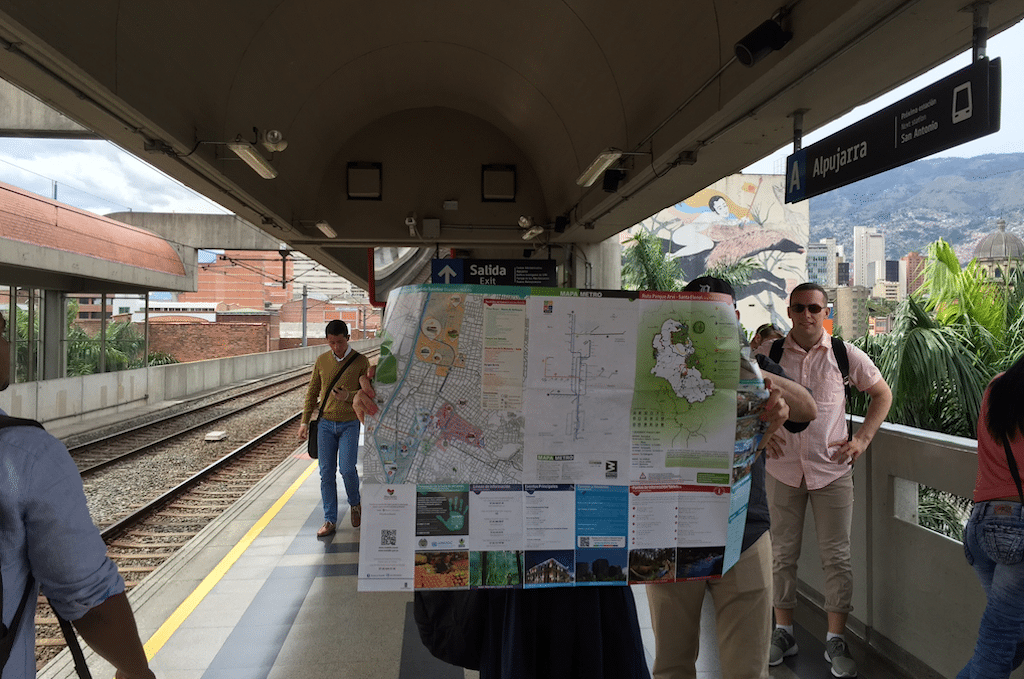

Indeed, Colombia’s second-largest city has undergone what appears to be a near-miraculous transition. The murder rate of 6,349 homicides in 1990 plummeted to 658 in 2014. Formerly high-crime neighborhoods such as Comuna 13, which hosts the escalators, welcome tourists as the city, under the current and three previous administrations, has poured money into social programs, including Medellin’s first metro, cable cars that are used as transportation for commuters living in the city’s mountains, and housing, including 20,000 newly constructed units for the poor.

The Skift team, visiting Medellin May 11 to 15, had a chance to discuss the city’s metamorphosis with Felipe Hoyos, the city’s vice mayor, and Pablo Velez, secretary of economic development.

Hoyos said Medellin has been able to pour so much money into social programs because of public-private partnerships but mostly because it owns the utility, Empresas Públicas de Medellín (EPM), which provides city residents with electricity, water, and telecommunications services. EPM generates about $1 billion in profits annually and about half of that goes into social programs, Hoyos said.

The Medellin Convention & Visitors Bureau has decided to focus on promoting the city as a business destination for meetings and conventions and it will host a United Nations World Tourism Organization general assembly this year.

Medellin welcomes leisure travelers, Hoyos said, but it has disadvantages when competing with other tourism destinations. He said the city doesn’t have an ocean, beaches or skiing, although it does have beautiful flowers, the Andes mountains, bird-watching, extreme sports, and religious and colonial-themed tours.

Medellin also competes against Cartegena for meetings and conventions, Hoyos said.

Medellin’s airport is small but under-used as it can support about 50 percent more capacity than it currently does. It also needs more direct flights, which it competes with Bogota for, especially international long-haul ones.

Five-star hotels are lacking in the city, too, although one or two are on the way, he said.

“We have a couple where they think they are five stars but they are not,” Hoyos said.

Still, Medellin is in the process, Hoyos hopes, of privatizing the CVB, and then turning the 50-employee organization into one that is “fully funded.”

A hotel room tax is also under consideration.

It is all part of Medellin’s transformation, a process that not only turns the city around for its inhabitants but also does a long way toward fixing its reputation as an attractive venue for meetings and conventions.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: colombia, medellin, meetings and events

Photo credit: Medellin's metro has spawned "metro culture," which amounts to local pride in a well-run and clean transit system. Skift