The Government Agency That’s Sending Good Planes to the Aircraft Graveyard

Skift Take

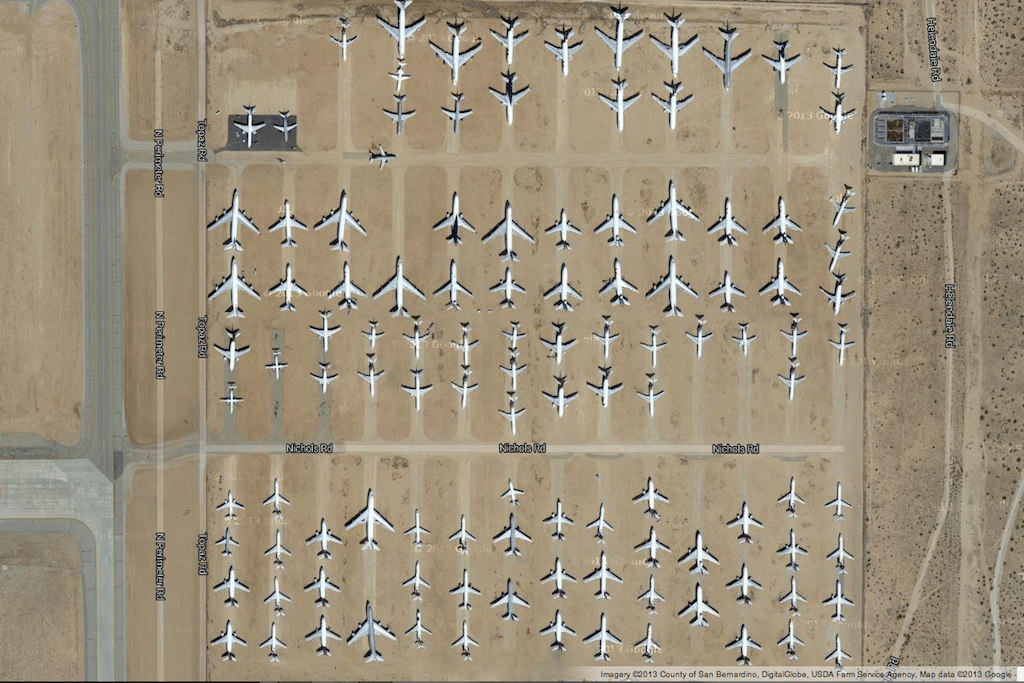

- The Southern California Logistics Airport, a ‘transitional’ facility for commercial aircraft, stores second-hand planes. Many won’t make it out whole, as the current market favors disassembled parts and scrap metal over used planes.

- Planes lined up at the Southern California Logistics Airport.

- An aerial shot of the Southern California Logistics Airport, in Victorville, California.

- A dusty, retired United Airlines Boeing 767 at Southern California Logistics Airport, in Victorville, California.

For a while after September 11, 2001, it looked like it would take a miracle to get the finances of the world’s airlines back off the ground.

Of course, it didn’t. Instead it took a series of well-executed government interventions, not the least of which was a popular financing program run by the United States government’s Export-Import Bank.

The “Ex-Im Bank” is the U.S.’s Export Credit Agency, similar versions of which exist in various countries throughout the world. Since the early twentieth century, such agencies have helped boost domestic manufacturing by guaranteeing loans to foreign companies for the purchase of those domestic products.

For instance, the U.S. Ex-Im bank guarantees loans to foreign airlines for the purchase of new, U.S.-made Boeing aircraft. The airlines are in it for the favorable terms – with the reduced risk a federal guarantee provides, banks will lend them more money at lower interest rates. Boeing is in it for the guarantee that it will receive payment for its aircraft even if the airline buying them goes under and has to default on its loan.

The government is in it for the national economic boost – or at least stability – that comes from the success of huge companies like Boeing, which employs 170,000 people and affects the finances of even more who work in partner companies or own equity in Boeing.

In recent years, that meant helping ensure that an economic slump didn’t decimate the huge and valuable aircraft manufacturing industry.

Use It Or Lose It

But since ECAs only finance brand-new aircraft (as well as used planes never before exported), their irresistible loan terms have made second-hand planes a bad deal by comparison. “Used purchases may require more cash,” said Boeing’s APR Communications Director John Kvasnosky, “which may or may not be available.” More often, the cash is not – especially in this era of airlines’ stable yet lower profits.

Historically, low-cost airlines and those operating in developing countries have provided the market for second-hand aircraft that are purchased second hand after they have seen ten or fifteen years of use by major carriers. But that market has dried up. Up-and-coming airlines are more reliant than any on the quick and cheap financing the U.S. government provides for brand new Boeing planes, which will last them a good 25 years to boot.

Instead, those major carriers’ planes are retired after little more than a decade of use. Though they are optimistically stored and maintained in Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Centers (AMARCs), where they’re available for resale, most will never fly again.

Domestic Loyalties Split

While government credits have been great for manufacturers like Boeing, their policies put domestic airlines at a disadvantage. The export credits only apply to foreign airlines buying U.S. planes, so U.S. airlines don’t qualify for the guarantees. They have to find some other (more expensive) source of capital to finance big purchases.

That disparity became controversial, and it was addressed in recent regulatory changes, according to Arsalan Ali, a member of the Price Waterhouse Coopers team that wrote its latest Aviation Finance report. The reforms, driven by arguments in favor of evening the playing field, won’t qualify domestic airlines for the guarantee, although Ali noted that some do receive ECAs for limited number of pre-allocated purchases. Instead, under the new rules, ECA financing for foreign airlines simply “won’t be as cheap as it used to be,” Ali said.

Even if that slows the rapid growth of airlines in Asia and the Mideast, which have benefitted the most from these credits, it will be hard for any U.S. airline to close the gap created by the decade of cheap and easy financing enjoyed by their competitors to the East.