Skift Take

The world’s three largest cruise lines are desperate to stop their $60 billion financial bleed. Destinations have experienced life without megaships for more than year. Is this the end of mass cruising as we knew it or can cruise lines find a place in a more balanced and diversified tourism economy?

A year into the unprecedented global pause of the world’s largest cruise lines, no other segment of travel faces a more uncertain future, nor as much of a massive transformation to its business model. Beyond the ship’s decks, far-reaching implications loom for those destinations with an outsized dependence on large cruise ship tourism and its ripple effects.

Megaships remain synonymous with risk in the eye of an increasing number of consumers as the industry struggles to regain its clout. The public relations scar might run deeper than the industry likes to admit. A recent survey of 600 cruisers and non-cruisers in the UK and Australia, for example, revealed that 47 percent did not trust cruise lines to look after them if something went wrong during a voyage, while a staggering 67 percent were less willing to cruise because of the pandemic.

The livestreams and news images of last year’s Covid debacle at sea remain etched in the minds of travelers — customers and crew indefinitely trapped in their cabins on the 2,666-passenger Diamond Princess, off Japan’s coastline, then stuck in port for three weeks while authorities in hazmat suits circulated ship corridors and dead bodies on stretchers were offloaded in port. More than 1,500 people were infected on Carnival Corporation’s ships and over a dozen died in what became the largest concentration of Covid cases outside of China at that time. Then came the suicides of global crew stuck aboard for months while the world was on lockdown.

But despite that harrowing year, the cruise industry remains optimistic, citing consistent pent-up demand from cruisers. At the start of 2021, Carnival said its advanced 2022 bookings surpassed 2019 levels. Over 150,000 people have also volunteered for test sails on Royal Caribbean, according to the cruise line.

Vaccine availability is another major light at the end of the tunnel. “I do think that the low hanging clouds are lifting and of course the vaccine is a game changer,” said cruise tourism veteran Carolyn Spencer-Brown. “I don’t see how you would [cruise] otherwise or why you’d want to.”

Opinions are split among cruise fans, however, about a pre-sail vaccine mandate — while some are willing to get jabs to get back on megaships, others have gone as far as calling for a boycott of the cruise line requiring them. Carnival is currently the only major cruise line that has not announced a vaccine requirement.

For now, cruise tourism remains largely paralyzed by continuing Centers for Disease Control (CDC) restrictions, updated days ago, and a Canada no sail ban until February 28, 2022. Just two major lines have been sailing since 2020. MSC Cruises began operating the 6,300 passenger MSC Grandiosa in August 2020 in Italy.

Ken Muskat, MSC Cruises USA’s chief operating officer, told Skift that more than 55,000 guests had been welcomed on board since that time. Royal Caribbean’s 4,905-passenger Quantum of the Seas has also sailed with Singapore residents out of Singapore — but to nowhere.

Meanwhile, the three largest cruise lines’ debt continues to rise, currently valued at approximately $60 billion, as they prune their fleets. This week, Carnival threatened to pull its ships out of U.S. ports if the CDC restrictions continue; the world’s largest cruise company has retired 19 of its ships out of 107, a move which CEO Arnold Donald said would delay the company’s recovery to 2023. By contrast, Donald’s compensation in 2020 amounted to $13.3 million a $2 million increase over 2019.

Covid-related passenger and shareholder class action suits have also emerged against a number of cruise lines. Skift contacted the Cruise Lines International Association, but did not receive a response. Attempts to reach Carnival and Royal Caribbean also went unanswered.

Small expedition ships, on the other hand, will be able to sail their backyard this summer. “The close to home bubble kind of cruising looks like it’s going to move forward, with possibilities for the UK, Australia, US flagged small ships that don’t have to petition the CDC for permission,” Spencer-Brown said.

But how has the absence of megaships affected ports of call? From Venice’s fresh ban on large cruises docking in the historic city to Key West’s law blocking large ships facing a legislative battle and industry pivots in Alaska and Grand Cayman, a range of destinations offer glimpses of the economic, social and environmental impacts of a year with no cruises.

Alaska: Pushing for Air Travelers

In 2019, 60 percent of visitors traveled to Alaska by cruise ship versus 36 percent by air, and four percent by ferry, according to the Alaska Travel Industry Association. Just like the size of ships, the cruise industry there had been growing exponentially.

“There are definitely people suffering because cruising had so overwhelmed Juneau and our economy,” said Karla Hart, activist and founder of Juneau CAN Rethink Tourism, a group of residents advocating for tourism alternatives beyond mass cruises.

“There are businesses that have grown up completely around the cruise industry that have nothing right now,” said Hart, citing whale watching and helicopter tours as examples.

Hart said downtown Juneau resembled “a boarded up theme park that got abandoned for a year.” – March 2021

With a second canceled cruise summer season ahead, the Alaska Travel Industry Association (ATIA), a 600-plus member group ranging from small businesses to large cruise line executives as partners, said it was supporting efforts seeking a temporary waiver from the U.S. Passenger Vessel Services Act to bring back big cruises to Alaska.

ATIA’s CEO Sarah Leonard recognized that was unlikely to happen by the summer. As a result, in January 2021, the group’s focus changed. “We have shifted our marketing messages to the air traveler or independent traveler, as we know they can access Alaska right now and in a safe way,” Leonard said.

But will cruise tourism numbers convert into a higher overnight tourism count?

“I don’t think we can replace the record breaking numbers that the cruise industry was projecting prior to the pandemic and that’s not really our goal,” Leonard said. “Our goal is to create some sort of economic activity for businesses across the state.”

The conversation surrounding the future of Alaska’s tourism, however, is stretching farther than this summer’s outlook. Last month, Skagway’s Mayor Andrew Cremata raised the potential of placing a cap on daily cruise visitor numbers at an assembly meeting. Skagway’s cruise economy brought in $160 million in 2019 and one million passengers. When cruises were in town, Skagway’s 1,000 residents would see up to 15,000 cruise ship visitors a day downtown.

“The community has been deaf to people’s concerns about overtourism,” Hart said. “But is there a way when we return, to have some balance so that you can make enough money to live, but you don’t have to make a killing?”

Hart has been working on cruise-related ballot initiatives for Juneau’s October 2021 elections.

A Juneau Visitor Industry Task Force established in 2019 submitted recommendations to the Juneau Assembly last year to limit cruises to five ships a day and prohibit hot-berthing, among others. A decision remains pending.

According to Leonard, the Alaska Tourism Industry Association had begun having industry discussions on overtourism pre-Covid and was about to employ a resident attitude survey statewide just before the pandemic.

“We’re trying to stay on that path of recovery,” Leonard said, adding that ATIA would return to those conversations later this year. As an association, however, Leonard said it would remain neutral if an Alaska destination decided to put a cap on its number of cruise ship visitors. “I respond to a board of directors,” Leonard said.

Meanwhile, small expeditions will begin sailing to Alaska again this summer. Princess Cruises and Holland America are opening up their lodges to the public, while affiliate Gray Line Alaska has pivoted to offer multi-day land-based tours to the public, taking travelers on the Alaska Railroad and on coach buses.

“I think that is a brilliant innovation,” Spencer-Brown said. “That’s a chance to really get into the interior.”

Perhaps the biggest ray of hope for Alaska comes from the airline capacity increase for the 2021 summer season by 800,000 seats over 2020. According to Anchorage International Airport, passenger service has been above the national average throughout 2020, and the trend is expected to continue this summer at just 7.3 percent below the record 2019 summer levels.

Airline seat capacity to Alaska for the 2021 summer season is up roughly 800,000 seats over 2020! This is tremendous news for the tourism industry, small businesses & our state, as the average visitor coming by air spends nearly $1,700 while in Alaska. https://t.co/KtPEH578X4

— Governor Mike Dunleavy (@GovDunleavy) March 2, 2021

Venice: In Perpetual Limbo

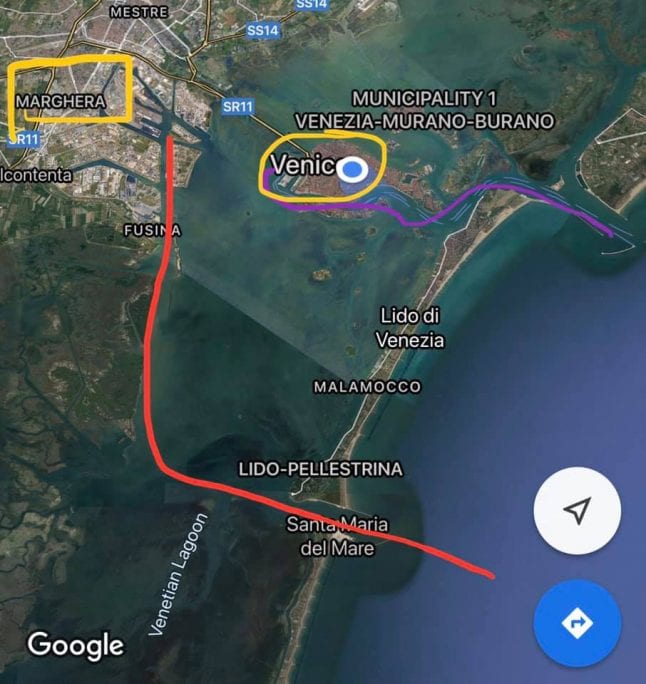

After a year that left residents uncertain on the return of megaships, last week the Italian government announced an official ban on cruises docking in Venice. As a temporary solution, megaships will sail across an industrial shipping channel and dock in Marghera, across the lagoon from the historic city. Officials also launched “a competition of ideas” on docking options away from the Venice lagoon and “to solve the problem of the transit of large ships in Venice in a structural and definitive way.”

“What’s bad for Venice isn’t going to be good for anywhere else,” Jane Da Mosto said, a 25-year Venice resident and co-founder of advocacy group We Are Here Venice, describing the decision as another lost opportunity to address the root cause of Venice’s mass tourism problem.

“This and similar measures have been promised before and never materialized, how can we trust that the government will deliver when the positive headlines have died down?” said Da Mosto, noting that bringing large cruise ships to Marghera would still not protect the lagoon, but rather continue to damage its fragile ecosystem. “No one is telling the industry to scale down and clean up.”

Da Mosto said that bringing large cruise ships to Marghera would not protect the Venice lagoon.

According to Da Mosto, last summer Venice experienced four months when it was pretty normal, from July through October 2020. Independent travelers rather than cruisers came to Venice to see it without hordes of tourists and enjoyed locally owned restaurants.

The Veneto Region’s statistics showed healthy visitor numbers for Venice, reaching up to 1.14 million visitors in August 2020, and over 500,000 in July and in September. It’s the kind of tourism that Da Mosto said Venice could use more of post-pandemic.

Awareness campaigns on social media or in town around the future of Venice tourism have continued rolling out. A recent round is a “Back Soon (but better)” poster campaign from We Are Here Venice, whereby residents were invited to share their ideas and posters were then shared around the city’s walls.

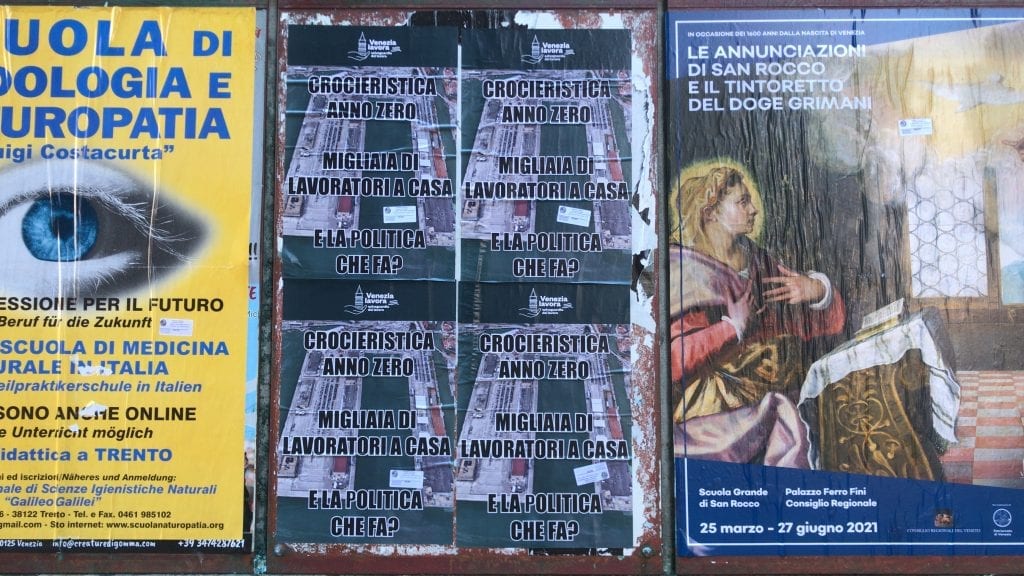

Da Mosto said Venice’s cruise-dependent unemployed workers have also posted their own messaging, demanding a solution to bringing the cruise sector back.

Port workers put up posters around Venice: “The cruise sector has gone back to the year zero, 1000s of workers are unemployed, and what are the politicians doing?”

“And our answer to it is, what are the politicians doing about the green jobs for the ex-cruise workers? That’s what we should be talking about because there were reasons before the pandemic for the cruising to be completely rescaled. There’s now all those reasons plus one: the pandemic.”

Meanwhile, cruise lines have not disappeared from Italy’s coastlines — the MSC Grandiosa, MSC Magnifica, and Costa Deliciosa, which is part of Carnival, started sailing there in the summer of 2020, and again this year despite ongoing Covid lockdowns in Italy.

“MSC Seaside will be deployed in the Mediterranean starting May 1, 2021… with two new ports of call for MSC Cruises — Siracusa in Sicily and Taranto in the popular Puglia region of Italy,” MSC Cruises USA’s Muskat said, while remaining silent on a question about Venice.

Last fall, David Landau, a curator and scholar who has lived in Venice, penned a five-point solution for Venice’s rebound which was later published in the local paper as an open letter to then-Venice mayoral candidates. It suggested, in part, building a port in the Adriatic, with passengers ferried into the lagoon or city. On a World Monuments Fund panel last month, Landau said his letter had gone unanswered.

A move away from mass tourism and towards “a new type of tourism that takes into account social and environmental justice” is what Da Mosto said would be suitable for climate vulnerable Venice.

“It’s not wacko to be saying these things, a while ago it was wacko and I was saying it then. But now we really can say it and expect that the mainstream will make space for it.”

Cayman Islands: In Cultural Preservation and Election Mode

Caymanians were getting ready to vote in a people’s referendum on a controversial new cruise berthing facility when Covid hit. And then, Cayman Islands’ Premier Alden McLaughlin surprised locals by backtracking this year on supporting the development and big cruises.

“I think that by the time Covid hit, the government knew that they were going to lose,” Troy Leacock said, owner of Crazy Crab, a private boat charter business offering small- group snorkeling excursions. Leacock was part of the anti-berthing movement.

Premier McLaughlin then said to local reporters that when cruises do return to Cayman, the government would consider putting a cap on the number of visitors.

“At this time, no such cap has been officially established,” Cayman Islands’ tourism minister, Moses Kirkconnell, told Skift in a statement, noting that it was too early to confirm any government measures given that cruises are not likely to return until 2022.

Prior to Covid, the British overseas territory received nearly two million visitors in 2019 on an archipelago of approximately 65,000 residents. Kirkconnell did not link a potential future cruise visitor cap to overtourism issues. “Implementing a potential cap is designed to ensure that all recommended safety measures are adhered to and enforced,” Kirkconnell said.

So far, a successful vaccination roll out — as of April 1, 47 percent have received a single dose while 31 percent are fully vaccinated — is positive news for Cayman Islands’ tourism industry, which has been closed for longer than most.

“We’ve gone from doing 100 charters a month to doing four or five charters a month; really and truly there is no business, because it’s purely the domestic market,” Leacock said, adding that only 20 percent of Crazy Crab’s business came from cruisers looking to escape crowds.

Boat businesses that catered to cruise crowds of 75-100 passengers remain unable to operate. Crazy Crab is surviving from loans and government grants, as well as 60 percent fewer staff. “We’re still operating but we are scraping every penny together to survive until the reopening.”

Leacock is currently involved in advocating for a more equitable tourism industry on the Cayman Islands. “I’m a part of an association that is currently being formed, the Caymanian Watersports Association, to create standards, certain regulations to push for Caymanians in our industry,” Leacock said.

The destination’s open economy and market had led more non-Caymanians to take over the watersports segment, according to Leacock, including fishing and snorkeling — traditionally Caymanian-owned and operated activities.

“When things are going well, you tend to ignore the inequities that are in a particular industry,” Leacock said. “But when everything grinds to a halt and you think about it … can everyone survive? Should you put protections for Caymanians in the industry?”

The imbalance isn’t just in water sports, according to Leacock. “We have a problem in Cayman that most of our tourism industry is not staffed by Caymanians, so we have a feeling here that it is necessary for us to ‘Caymanianize’ our tourism industry, to make sure that the visitor experience here still incorporates Caymanian culture, Caymanian history.”

The Cayman Islands’ government said it was focused on stimulating the tourism economy, such as pushing its digital nomad “Global Citizen Concierge Program” launched in October 2020. “We have processed more than 125 applications and welcomed more than 100 remote workers to the Cayman Islands,” tourism leader Kirkconnell said.

For Leacock, a general election on April 14, 2021, could bring in a new government and a new cruise tourism outlook. “Because we’ve had to live without it, I think that it’s going to embolden many of us, and hopefully a new government to say: these are the terms now under which you visit our country,” Leacock said. “We can have an entirely different cruise industry than we had pre Covid — much higher quality, much more profitable for the people and operators in Cayman.”

The Caribbean: A Rise in Homeports

Thirty million million cruisers visited the Caribbean in 2019, the cruise lines’ most lucrative region, according to the Caribbean Tourism Organization (CTO). Cruise tourism fell by 72 percent last year with 8.5 million cruise visits, primarily in the first three months of 2020.

Caribbean destinations have remained eager to see the restart of mass cruising, though a handful of islands were eyeing opportunities for smaller, “higher value” cruises and a chance to finally be considered worthy of home-porting by the big cruise lines in light of their delayed ability to sail out of the U.S.

In addition to Royal Caribbean, last month Crystal Cruises and The Bahamas announced their home-porting alliance for 16 sailings across the archipelago, departing and leaving from The Bahamas starting in July 2021.

“Home-porting brings with it considerable opportunities for economic linkages within our economy — the benefits of guest expenditures, crew expenditures, and port fees will translate into dollars spent directly in our communities,” Joy Jibrilu, director general of the Bahamas ministry of tourism, said in a statement.

Jibrilu was unable to provide projected economic revenue from this new home-porting agreement. “Because of the fluidity of Covid, the booking window to travel to The Bahamas is shorter than normal, and as a result it is difficult to say,” Jibrilu said recently.”However, Easter is trending stronger, and they are forecasted to strengthen by the 4th quarter of 2021.”

CTO data for 2020 showed overall tourist arrivals in the Caribbean region reached just over 11 million or a 65 percent decline over 2019, despite no cruise arrivals — lower than the 73.9 global tourism decline.

Key West: Booming and Resisting

After a historic vote in 2020 banning big cruise ships from its community, Key West’s residents are facing off with Florida legislators who are seeking to overturn their vote.

If it passes as law, Senator Jim Boyd’s (R) State Preemption of Seaport Regulations bill (SB 426/HB 267), would prevent local municipalities from making decisions that restrict or regulate commerce at their ports and reverse Key West’s large cruise restrictions, which are currently law under the city’s charter.

While the battle is unfolding, the real-life outcome of last year’s referendum efforts from Key West citizens is being lived on the ground.

“It’s crazy because we’re in a pandemic and we read the news around the rest of the world that not everybody is doing well, but here tourism is booming,” said Arlo Haskell, co-founder of the Key West Committee for Safer Cleaner Ships, the group behind Key West’s referendum initiative. “They said our economy would crash without cruise ships. But we’ve gone a full year without them and our economy is booming. ”

“Overall, the town is packed,” according to Analise Andrews, owner of Key West Food Tours.

Despite the lack of cruises, Florida Keys’ total sales tax revenues for September–November 2020 exceeded the same period for 2019 or $1.1 billion versus $1 billion in 2019, while STR’s 2020 report on Florida markets showed Key West as having the highest year to date occupancy levels in the state and the highest revenue-per-available-room, a key hotel metric. From June to December 2020, data from the city of Key West finance department also confirmed that businesses at Key West Bight, part of the city’s port, did as well as pre-pandemic numbers or better.

“Since probably the beginning of February, the foot traffic I see downtown is very similar to that of having cruise ships here,” said Megan Coccito, Kimpton Key West’s director of sales and marketing. “Since Thanksgiving, we have been selling out every weekend and 80-85 percent on weekdays up until Christmas, and then starting around Christmas time, we’ve been selling out almost every day of the week.”

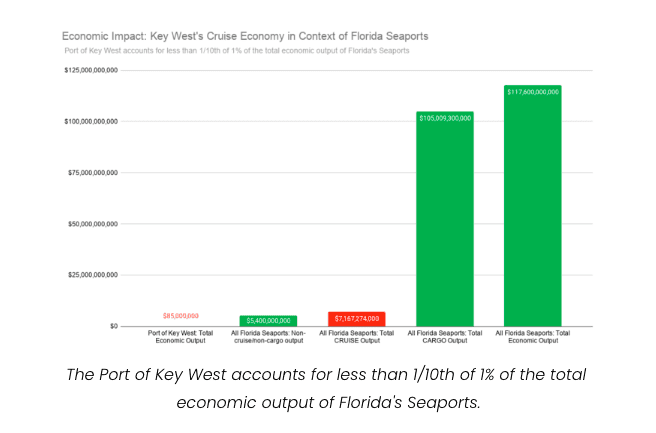

“The economic picture is so different for ports of origin versus ports of call,” Haskell said, as to why Key West’s big ship ban would not affect Florida’s economy.

Visitors are mostly from drive markets, including Florida, New England, the Midwest, and a larger than usual number from the Carolinas. Making last minute weekend plans would cost you $1,500 a night, according to Coccitto, noting she had never seen such a boom in her time living in and working for hotels on Key West since 2005. Restaurants are equally packed and posting employment ads.

Analise Andrews, owner of Key West Food Tours, agreed. “Overall, our food tours were doing about 75 percent of what we were doing last season, so really good,” Andrews said, while noting that the owner of a small mom and pop restaurant did report being down by about 55 percent. “And it’s direct cruise ships, because they’ve never had a problem at night, when they’re filling up the restaurant.”

But Andrews said that businesses affected by the cruise ships were minimal, given the current crowds and that cruisers didn’t spend much money off the boat. “There’s a lot of people spending money right now,” Andrews said. “I think if anything, the pandemic grew the popularity of Key West and the Florida Keys as a destination.”

Evan Haskell, Arlo Haskell’s brother and president of the Key West Committee Safer Cleaner Ships, has co-owned We Cycle Key West since 2009. “Since September, I’ve rebounded back to normal, recently like quite above 2019 numbers. I’m tracking 10 to 20 percent up per month.”

Last week, one of the preemption bill proponents’ arguments that cruise ships did not harm Key West’s waters or its reef fell apart. A new Water Quality Monitoring Lab report by Dr. Henry Briceño at Florida International University’s Institute of Environment released hard data showing that “waters south of Key West, during the year 2020 were among the less turbid waters in the last 25 years,” after comparing the one-year shutdown period against 1995-2019 measurements in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary.

“The arguments for large cruise ships in the Florida Keys have been exposed as a pack of lies,” Arlo Haskell said. “The data is out… proving that our fishermen and divers were right all along. The transformation we’ve all seen with our own eyes is now scientifically proven. Nature is in fact starting to heal.”

According to Haskell, the Great Florida Reef was now more than 90 percent dead and on its last legs. “We are on the brink of an ecological disaster,” Haskell said, adding that forcing large cruise ships back into the Florida Keys would hasten the demise of the world’s third-largest barrier reef. “This would be a historic mistake.”

While the bill advances in the legislature, Key West advocates, plus 24 environmental groups, have appealed to their state governor. Anti-mask mandate governor Ron DeSantis, who kept Florida open for business throughout Covid’s spikes, recently threatened to sue the CDC if it didn’t lift its conditional sailing ban. But the Haskells said that he has previously shown “backbone” in standing up against powerful corporate interests to defend the environment. “He did it for the Everglades against Big Sugar,” Arlo Haskell said.

As the big cruise lines continue facing ongoing restrictions from the CDC and restart delays, their year ahead is likely to prove more challenging than the last — from restoring consumer confidence and facing increased community push back against big ships, to dealing with governments under increased pressure to regulate the environmental and overtourism impacts of mass cruise tourism.

“We have to constantly remind people that Key West’s economy and the Florida tourist economy is about the environment — that’s why people come here, it’s because it’s a beautiful place to be, and that goes away if you don’t take care of that.”

The Daily Newsletter

Our daily coverage of the global travel industry. Written by editors and analysts from across Skift’s brands.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: coronavirus, coronavirus recovery, cruises, overtourism

Photo credit: The overwhelming majority of cruise ships stood moored for the past year as the pandemic took its toll on the industry. Allen Allnoch / Getty