Skift Take

A new white paper critiques today's industry mania for mergers, which is driven by a fear of rising digital gatekeepers such as Airbnb, Google, and Expedia. The contrarian take is refreshing but begs questions.

Management consultants famously borrow your watch to tell you the time.

A possible case in point may be a new white paper created by the management consultancy A.T. Kearney and sponsored by travel technology giant Amadeus.

The consultants quizzed external industry experts about how 70 trends — from nationalism to the rise of new programming standards — might change the distribution of airline and hotel inventory.

The management consultants have come back with four possible scenarios. By a happy coincidence, they found that “the traditional aggregator for the travel industry — global distribution systems [meaning, companies like Amadeus] — will remain relevant under all scenarios.”

It seems that “hubris leading people to be caught by surprise” was not one of the 70 trends analyzed by the authors of the report.

The critique here is not that the Madrid-based distribution giant is likely to disappear in a decade’s time. On the contrary, publications like The Economist have called like Amadeus “the ineluctable middleman” for good reason.

The critique instead is that the report would have gained in persuasiveness if it had entertained the idea that so-called “black swan” events may catch executives off guard.

Forget “go big or go home”?

That issue aside, the white paper — “What If? Imagining the Future of the Travel Industry” — is compelling because it crystallizes and challenges some common assumptions.

One widespread idea that the report implicitly critiques is this: To deal with technological disruption, many executives think you have to “go big or go home.”

In other words, there has been a recent mania for mergers and achieving scale among airlines, hotel groups, online travel companies, travel management companies, cruise lines, wholesalers, and tour operators.

The report argues that the merger mania has been driven by many travel executives believing that they must consolidate and do more vertical integration to combat the growing power of “digital gatekeepers” that are heavily visited by consumers, such as Alibaba, Airbnb, Amazon, Expedia, Facebook, Google, LinkedIn, and WeChat.

But history suggests that the passion for consolidation is cyclical. The current push for achieving scale may also sputter out, predicts one of the experts spotlighted by the white paper — Martin Cowley, a one-time CEO of the Asia Pacific division of Amadeus’s rival Sabre and currently a consultant.

“There is a lot of anxiety in the industry about the encroachment of tech giants,” says Cowley. “Much of the anxiety is misplaced and could lead to poor investment decisions.”

Cowley argues that two factors that have halted consolidation in the past may rear their heads again soon: the complexity of merged operations (which often become unmanageable for executives), and a lack of consumer appeal (given that consumers have not historically fallen in love with one-stop shopping).

So what is a travel executive to do? If merging one’s way to greater negotiating power with digital platform giants isn’t the best choice, what is?

One option is to focus on understanding the needs of your customers and how to solve their unmet needs, according to one of the paper’s authors, Yelena Ageyeva-Furman, senior principal from A.T. Kearney.

“What we see across all industries is that, where there is a pain point for consumers, that is exactly where disruption is going to happen and where new players may challenge your company’s position,” she said in an interview.

Ageyeva-Furman advises racing to identify and solve points of friction before other companies beat you to it.

She cautioned that spending energy trying to defend against the perceived threat of giants like Amazon and WeChat can be a dangerous distraction.

Travel Industry Frenemies: A Love Story

The white paper cautions travel executives that the business case for gatekeepers like Google to try to intervene and take market share in travel is vulnerable to geopolitical events, such the threat of increased regulation and a closure of physical and virtual borders for both people and data.

The authors predict that, if the world opts for more openness, interconnectivity, and growth, companies like Google are more likely to invest in trying to take a larger share of the travel distribution pie because the potential rewards will be bigger.

For instance, a favorable, deregulated, globalized business environment would increase the potential rewards such platform companies could earn by investing in tools that enable the personalization of trips, where software programs can accurately predict the preferences of a traveler for details of their trips, from transportation to the type of pillow they like when sleeping.

Yet regardless of how geopolitical events play out, the report argues that executives should focus more on how to gain or maintain competitive advantage in specific niches and segments of their business and be willing to cooperate selectively with tech “gatekeeper” platforms like Google and Alibaba to the extent those partnerships can improve one’s market position via one’s other immediate rivals.

Alex Luzarraga, vice president of corporate strategy, said in an interview that he thinks the platform companies not specialized in travel, like Alibaba, Amazon, and Facebook, and the ones that are specialized, like Airbnb, Expedia, and Uber, aren’t going to go away.

But their size shouldn’t scare travel suppliers. There is more to gain by seeking partnerships with them.

Luzarraga thinks travel companies can thrive if they look for ways to complement the tools that technology platform giants (Google, Alibaba, etc.) provide consumers with their solutions. Examples he gives include providing richer travel content to enhance the data those platforms already have, or by marrying data sets to provide more personalized service to customers during the booking process.

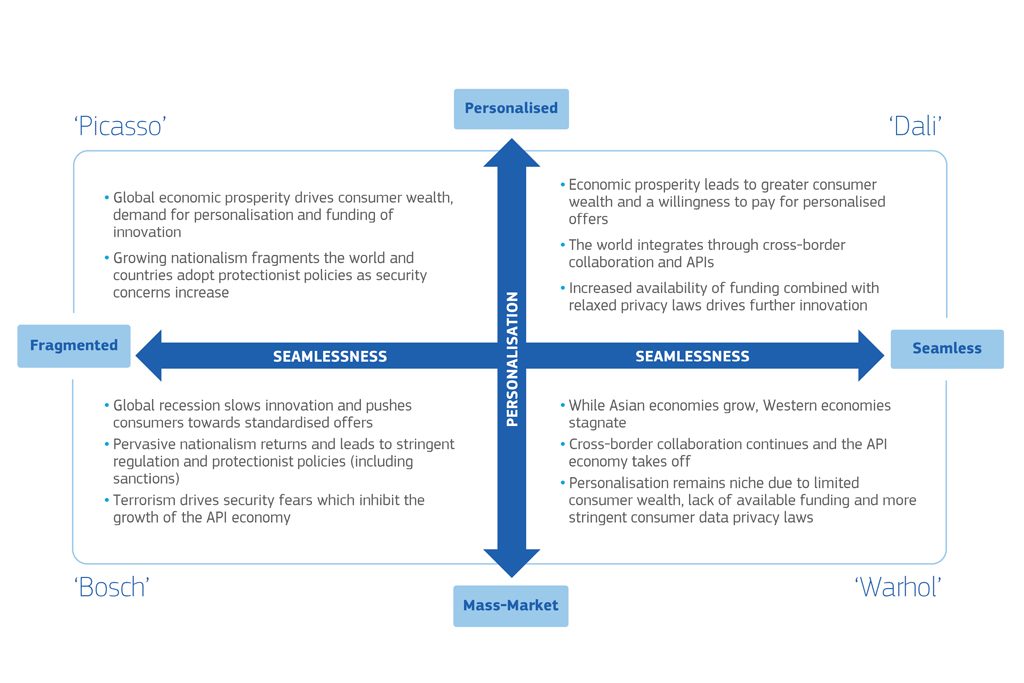

To its credit, Amadeus didn’t push A.T. Kearney to specifically predict the future of the world and its impact on travel distribution. The paper sketches out four scenarios, and doesn’t say one is more likely than the other.

Some people may find that frustrating. (“Just tell me what’s going to happen and what to do!”)

Yet the track record for predictions by experts isn’t great. Large-scale studies testing the accuracy of predictions by experts show they’re often no better than chance, according to “Superforecasters,” a 2015 book by Wharton professor Philip Tetlock.

Amadeus advocates that travel companies do similar scenario-planning exercises for stress-testing their company strategy. Your company could come up with a handful of industry outlooks and assess how those trends — from regulations to demographic shifts to new consumer behaviors — may affect your company’s strategy.

Once you’ve described the scenarios, you can monitor trends. When one scenario of the bunch appears to be materializing, you can act accordingly by implementing a plan rather than reacting in an uncoordinated way.

Sadly, the paper doesn’t give advice on how to structure scenario-planning to avoid common mistakes, such as having excessive self-confidence in your own company’s impregnability. But by a happy coincidence, A.T. Kearney says it’s taking on new clients to do scenario-planning for them.

Here’s a pro tip: After they borrow your watch, be sure to ask for it back.

The Daily Newsletter

Our daily coverage of the global travel industry. Written by editors and analysts from across Skift’s brands.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: amadeus, future of travel

Photo credit: A white paper examining the future of travel distribution suggests traditional travel companies could benefit from partnering with newer platform companies such as Airbnb. Airbnb listings are pictured here. Bloomberg