Skift Take

Failing to ban something which affects the function of the seat trays in this manner, seems to put regulators at odds with their core responsibilities for cabin safety and component certification. But, for now, it's up to passengers to decide whether they want to take the risk and up to airlines and manufacturers to cope with any consequences.

In flight diversions alone, the controversial Knee Defender device, which costs passengers just over twenty dollars, has cost airlines dearly.

But industry insiders are concerned that the risks of injury during cabin emergencies resulting from use of this device could cost airlines and seat manufacturers far more.

Industry experts that look at unruly passenger incidents on aircraft have previously told Skift that each flight diversion may cost between $6,000 to $200,000 to an airline, but the liabilities associated with any injuries resulting from passenger use of the Knee Defender could be in the order of millions, some industry sources say.

Though the devices are purchased and used by the passengers themselves, these sources believe that in the event of an injury the legal representatives of the injured passenger could pursue claims against the airline, and even the seat manufacturer.

The reason for concern by those inside of the aircraft seating industry is that the Knee-Defender inherently impedes the proper function of the seat: not just preventing recline, but also locking the tray table in place. Aircraft seat tray tables have to be stowed during take-off and landing and in turbulent aircraft conditions because they are in the way of the forward dynamic movement of the passenger during cabin emergency conditions.

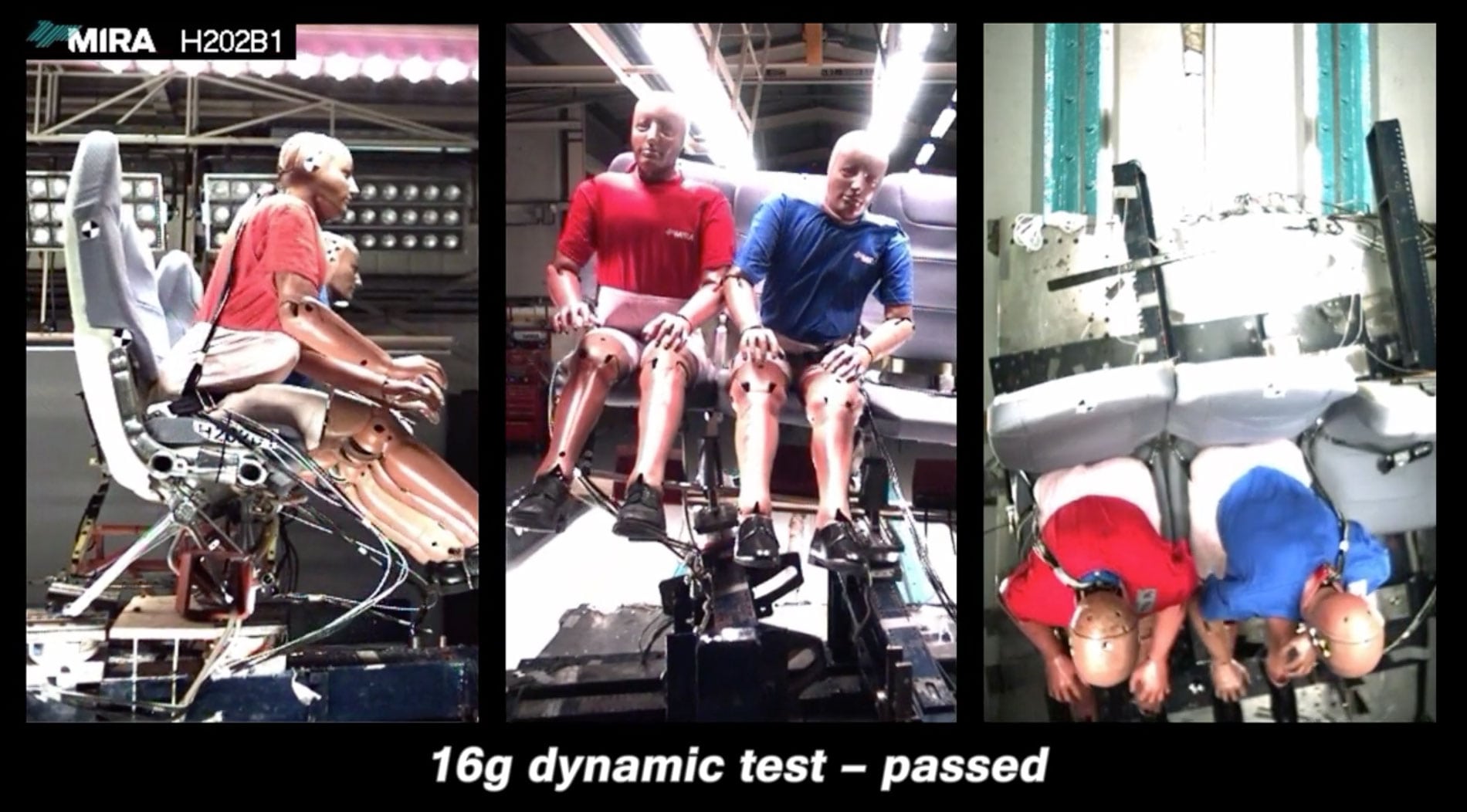

Aircraft seats are tested and certified to ensure that all properties of the seat can allow a passenger to be thrust forward with impetus up to 16 times the force of gravity. The structures are built to withstand this force, and the separation between the seats is tested to ensure that there is no risk of head injury or other injuries to the body in these conditions.

Those certificates are based on the seats’ original properties, and the safety procedures which require tray tables be stowed. Those tray tables also have hinges that give way, by design. Use of the Knee Defender interferes with the original design function of the hinges on those tray tables, locking them in place.

The Knee Defenders would have to be removed prior to stowing the tray table in the event of a cabin emergency. During unpredictable incidents, such as unforeseen severe turbulence, the passenger using the Knee Defender might not have proper warning or react in time.

A dynamic test for certification of commercial aircraft economy seats is shown in this video of the testing for Pitch PF2000, starting at minute 1:07.

Industry sources familiar with seat testing dynamics express concern over the physical risks to passengers, and the subsequent financial risks to the industry from such events.

“If there is a catastrophic incident and the legal community can show that a passenger was injured or killed due to the seat not responding properly as it did in dynamic testing, and this non-response was due to the application of the lock out device, in my opinion there will be a spirited legal contest to make the airline and the seat manufacturer financially responsible,” one source told Skift.

The Regulatory Position

While many airlines prohibit the use of the Knee Defender, use of the devices has not been banned by the regulators. This failure to ban a device which could pose a risk of injury—even if it is to the person who elected to use it—appears to some in the industry to conflict with the objectives of aircraft seating safety regulations.

Speaking to the conflict between the strict safety regulations in place for seat testing, and the current position from the regulatory authorities that a prohibition of the Knee Defenders should be left up to airlines, a source added:

“It would all come down to whether or not the measurement for passing Head Injury Criteria is violated with the installation of the lock-out device. If it is—and this would have to be demonstrated on every seat that is currently in service, and will be in the future certified to be HIC compliant—then the current position taken by the FAA [may constitute] allowing HIC requirements to be violated, when it is their requirement to begin with.”

Forward dynamic testing considers not only HIC but also risks of other injuries from the seat including to the internal organs—a major concern in being thrust forward against a lowered tray table.

Skift reached out to the FAA, UK Civil Aviation Authority (UKCAA), and EASA (European Aviation Safety Agency) to question their position on the use of these devices and the issue of safety risks associated with their use during unexpected aircraft emergencies.

When asked, Alison Duquette, FAA Communications, stated: “My understanding is that most U.S. airlines prohibit the device. While the product does not violate any FAA regulations, it is up to individual airlines to prohibit it. We expect passengers to comply with airline policies and directions given by the flight and cabin crew. The FAA discourages the use of any device that alters the performance of any part of an airplane. It’s never been tested by the FAA. So, this is a device provided by the passenger that has no certification.”

Richard Taylor, Corporate Communications for the UKCAA replied:

“Obviously, passenger seats must be in the upright position for taxi, take-off and landing, and anything that interferes with the ability of seats to be positioned upright, is therefore be a problem. However, it is the airline’s responsibility to ensure they comply with this requirement, so if a passenger installed device interferes with a seat (either locking it upright, or accidentally locking it reclined) then it is the airline that has to prohibit their use.”

“As these devices are not part of the aircraft, therefore not affecting its airworthiness, or do not pose a direct threat to the health of passengers and crew, we are almost certainly not in a position to ban them. We have to concur with the FAA, it is up to the discretion of individual airlines as to whether they allow the use of these devices.”

EASA indicated that it was looking into the matter, but gave no formal reply.

The UKCAA’s statement that there is no “direct threat to the health of passengers and crew” might be true during normal operating conditions, but those who worry over the lack of an outright ban on these devices are concerned with unpredictable cabin conditions.

When asked about the risks of injury during cabin emergencies resulting from a seat when a tray table was locked in place by the Knee Defender, the FAA said it had nothing more to say on this issue and the UKCAA did not reply.

The Daily Newsletter

Our daily coverage of the global travel industry. Written by editors and analysts from across Skift’s brands.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Photo credit: Testing for the Pitch PF2000 seat. Vimeo