Skift Take

Brazil should be looking at Germany for how it used the World Cup as an excuse to build up infrastructure rather than build too-big stadiums that were destined to remain dormant.

Monica Piaia’s catering company in downtown Cuiaba, the capital of the Brazilian grain-belt state of Mato Grosso, is doing so well that she has tripled her staff and acquired a third building since 2010 to handle a sixfold increase in demand.

The reason for her success is clear. A stone’s throw from her headquarters, where industrial-sized kettles bubble and delivery vans are loaded, 500 workers are toiling to finish one of the 12 stadiums nationwide that will host the 2014 soccer World Cup.

Three times a day, Piaia delivers food to workers there and at several of the 56 construction sites that will give Cuiaba new roads, a trolley and an airport terminal by June 2014, Bloomberg Markets magazine will report in its July issue.

“I never dreamed I’d see this kind of growth,” Piaia, 41, says, as the aroma of coffee wafts from the kitchen. “The cup is helping me and driving the city’s development by years.”

Brazilian policy makers are betting that the mega soccer tournament and the Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro two years later will provide a boost to a national economy whose growth slowed to 0.9 percent last year. That was a far cry from the 7.5 percent growth in gross domestic product in 2010 that had investors pouring into Brazil.

GDP growth

The World Cup will require 30 billion reais ($14.5 billion) for stadiums and urban transportation and add 0.4 percent a year to GDP growth through 2019, Brazilian Sports Minister Aldo Rebelo says. The Olympics will cost about the same, and both events will generate 3.6 million short- and long-term jobs by the end of 2014, he says.

Brazilian construction firms such as Belo Horizonte-based Mendes Junior Engenharia SA and Salvador-based Odebrecht SA have won many of the large contracts.

Foreign companies are also in on the action, from Los Angeles-based Aecom Technology Corp., which designed the Olympic Park in Rio, to Denham, England-based InterContinental Hotels Group Plc, which is tapping Brazil’s tourism potential.

“Without a doubt, these two events will be a window of opportunity for the country to consolidate its tourism image,” says Alvaro Diago, chief operations officer of InterContinental in Latin America. The company plans to triple the number of its hotels in Brazil to 39 during the next decade.

Eike Batista

Investors such as Brazilian billionaire Eike Batista and Los Angeles-based AEG Facilities see opportunities long after the government-estimated 3.7 million visitors for the cup have gone home. They plan to manage new or renovated venues, such as Rio’s Maracana Stadium, which holds 79,000 fans and was the largest in the world at the time it was inaugurated in 1950.

Batista, whose empire extends from oil to mining and entertainment, saw his net worth fall to $7 billion from $30 billion in mid-2011 after several projects soured, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index.

Foreign investors have already profited from stock purchases of the few publicly traded companies working on the cup and Olympics, says Eduardo Carlier, a fund manager at the Brazilian unit of London-based Schroders Plc.

Construction company Mills Estruturas & Servicos de Engenharia SA, a Rio-based supplier of scaffolding and concrete, tripled in share value to 35.65 reais on May 27 from 11.80 reais on May 13, 2010.

“Companies exposed to sporting events performed well, but bets with a direct relation to such projects are difficult to find,” Carlier says. Many such firms, including Batista’s joint venture sports and entertainment company IMX, aren’t publicly traded.

‘Too much’

Brazil, which has won five World Cups, more than any other nation, is eager to showcase its clout as the world’s sixth- largest economy. That enthusiasm may have led to decisions to spend too much, says Fabiola Dorr Caloy, a member of the team that the nation’s prosecutors created in 2009 to monitor spending on the World Cup.

Twelve cities will host the soccer event. The Corinthians Arena in Sao Paulo, named after the local soccer team that contracted its construction, will cost 820 million reais. That makes it the most expensive per seat — 17,100 reais — of any opening-day venue since Portal Copa 2014, an engineering news site for the World Cup, started tracking costs in 1998.

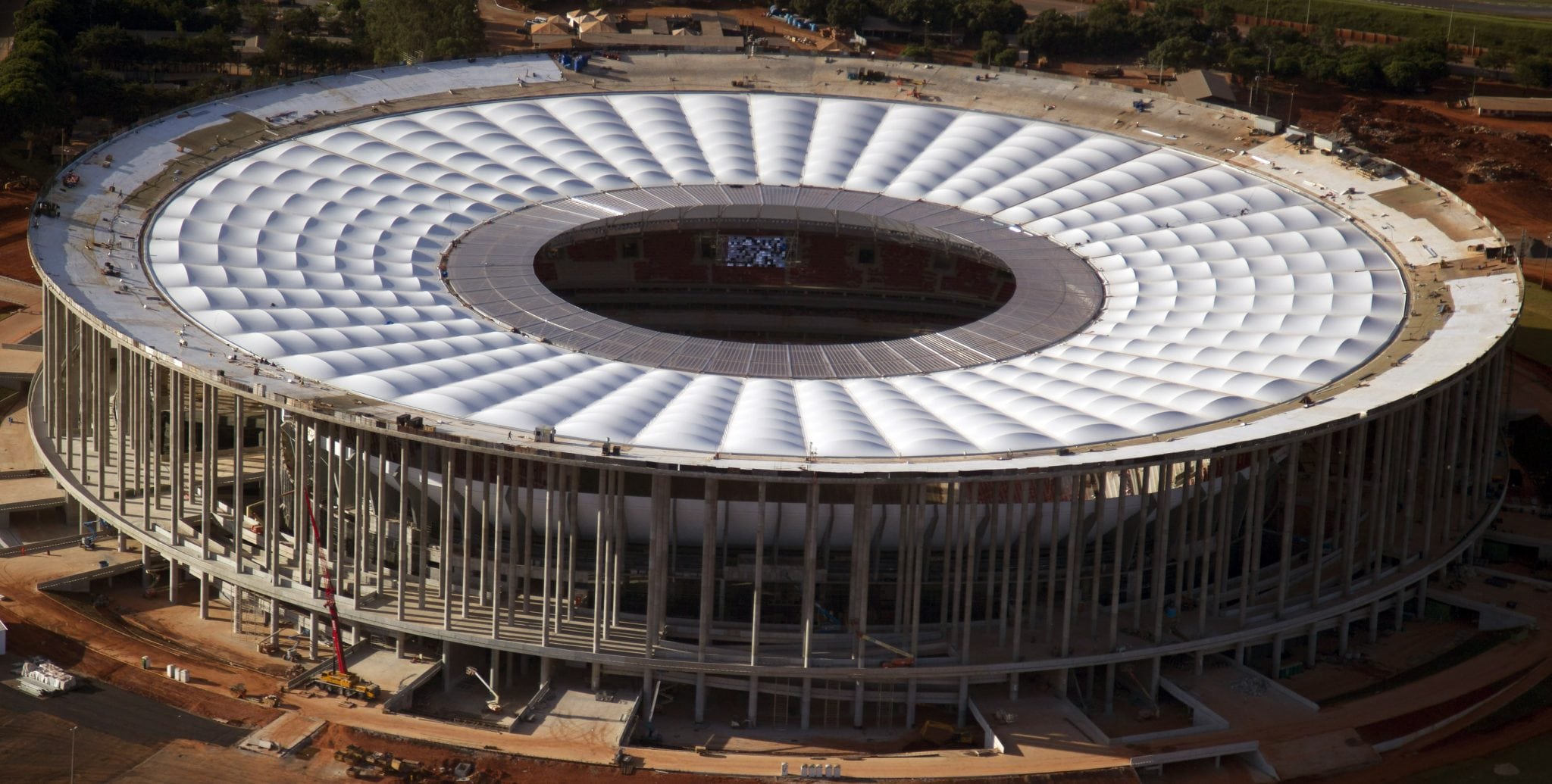

The risk is that some sports complexes will become unused behemoths, Caloy says. The site in Brasilia, the nation’s capital, is the most expensive in total cost, at 1.3 billion reais. It will have a capacity for 73,000 fans. A game between two popular local soccer teams drew 801 fans on March 31.

‘Futuristic metropolis’

That doesn’t mean new construction will go to waste, Sports Minister Rebelo says. Stadiums can be used for congresses, shows and other events, and they provide national prestige, he says.

“As the capital, Brasilia needs a stadium that matches its calling as a futuristic metropolis,” Rebelo says. “I don’t think they’ll be white elephants.”

In Brasilia, more than 80 percent of public schools have inadequate facilities, lacking chairs, books and water-tight roofs, according to the Tribunal de Contas do Distrito Federal, a watchdog.

In Cuiaba, trash lines walkways, and pedestrians in some neighborhoods bridge rivers of open sewage with boards. At least 70 percent of Cuiaba’s wastewater is untreated, according to Cia. de Saneamento da Capital, or Sanecap, the city’s sanitation utility.

Schools, hospitals

“We need more investment in schools and hospitals, not monumental works,” says Airton Pereira Lopes, a retired salesman in Cuiaba. “What do we need a new stadium for?” asks Lopes, 66, who says he had to wait 35 days for medical attention for his broken arm.

Mato Grosso’s roads also need to be improved, according to Famato, the state’s farm association. Brazil was the world’s top exporter of orange juice, coffee and sugar in 2012, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Soy may be added to that list this year. The hitch is that produce often can’t get to market on time, Famato says.

During the peak of the soybean harvest this year, trucks broke down every day, and others spilled part of their cargo navigating the state’s pothole-riddled roads on the way to port.

In March, a record 212 ships waited to load soybeans at Brazil’s ports with holdups as long as 54 days, according to Santos-based shipper and brokerage SA Commodities. Chinese crusher Shandong Chenxi Group Co. in March threatened to cancel supply contracts.

‘An outrage’

Farmers are furious that the state of Mato Grosso is using as much as 250 million reais in taxes earmarked for roads to finance Cuiaba’s World Cup projects, says Nelson Piccoli, Famato’s finance director.

“It’s an outrage,” he says.

Mauricio Guimaraes, who coordinates the World Cup event for Mato Grosso, says the government has made efforts to improve roadways.

“The poor state of the roads is not because we’re using those funds; it’s an historic problem,” he says.

The Rio state government says it will invest an estimated 21.5 billion reais for the Olympics. Part of that is for new roads, railways, overpasses, tunnels and upgrades to rapid bus transit and airport and maritime terminals, says Renato Villela, Rio state’s secretary of finance.

“Investing in urban mobility is some of the best-spent money,” Villela says. It will increase jobs and help keep the city of Rio’s unemployment rate at the lowest in Brazil, he says.

Spending pitfalls

The sports-venue spending in Brazil, though, is ripe with pitfalls, says Athayde Ribeiro Costa, who chairs the federal prosecutors’ World Cup monitoring committee. A 2011 law designed to accelerate procurement for World Cup projects allows contractors to amend proposals after winning a bid.

The price tag for the Brazilia stadium rose 30 percent to 1.3 billion reais after the contract had been awarded, according to the watchdog Tribunal.

“The law, which tried to make up for terrible planning, allows the executive to hire contractors without knowing what will be built,” Costa says. “It’s an invitation to corruption.” Some of the World Cup’s urban transportation projects won’t be completed on time, he says.

For some foreign companies, the sporting events are a springboard to more contracts in Brazil.

‘More hits’

The Olympics has heightened Los Angeles-based Aecom’s visibility and helped secure contracts for its nonsporting businesses, such as urban redevelopment and environmental consulting on energy, says Bill Hanway, executive vice president for buildings and places in the Americas.

“Our website had more hits than ever when the Rio deal was announced,” Hanway says. “For us, it’s important for the next 20 years.”

Because the public is willing to spend large amounts for entertainment and soccer, some of the multipurpose stadiums could lead to new work, says Bob Newman, chief operating officer of AEG Facilities. The company signed agreements last year to manage stadiums in Curitiba, Recife and Sao Paulo and expects to participate in three more locations in coming months.

“It’s a perfect storm being created for success,” Newman says.

Still, red tape and an unwieldy tax system make Brazil a challenging place for investing.

“Taxation was much more complex than we had originally estimated,” Hanway says.

‘It’s chilling’

Companies spend 2,600 hours a year dealing with tax issues compared with an average of 367 hours in the rest of Latin America, according to the World Bank’s ‘Doing Business 2013’ report.

“It’s chilling to international companies wanting to look at Brazil and make investments here,” Rebecca Blank, acting U.S. Commerce Department secretary, told reporters in Brasilia in March.

Piaia, the caterer in Cuiaba, says she sees no roadblocks. She expects her business to flourish for years to come.

“We’ve made a name for ourselves,” she says of her business. “The cup brought my ticket to success.”

Editors: Jonathan Neumann, Gail Roche. To contact the reporter on this story: Raymond Colitt in Brasilia Newsroom at [email protected]. To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jonathan Neumann at [email protected]. To write a letter to the editor, send an e-mail to [email protected] or type MAG <Go> on the Bloomberg Professional service. ![]()

The Daily Newsletter

Our daily coverage of the global travel industry. Written by editors and analysts from across Skift’s brands.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: brazil, events, rio, sao paulo, world cup

Photo credit: A general view of the National Mane Garrincha Stadium, seen under construction in Brasilia. Ueslei Marcelino / Reuters